Hey Folks,

As you’re probably aware, I’ve been exploring a very deep rabbit hole lately - the question of how civilization spread across the entire world, and how we can recast the story of humanity so as to create a social reality that is better optimized to human needs and desires.

My jumping-off point for this intellectual journey has been a 2021 book called The Dawn of Everything, which purports to offer “A New History of Humanity”, which I think is deeply flawed.

Throughout this research project, one thing has led to another. The original question that inspired David Graeber and David Wengrow to write The Dawn of Everything had to do with the rise of social inequality.

Eventually, they decided that this wasn’t a good formulation of the question they were really interested in, and they moved on to asking themselves how we got stuck in the current paradigm of governance, under which the vast majority of human beings live under the arbitrary power of unaccountable bureaucracies. There seems no particular reason why this should be so, given the innumerable forms of social organization that human societies can take.

The authors do raise some very good points about the very idea of equality, which they show didn’t even exist prior to the Conquest of the Americas. Apparently the idea of political equality can be traced back to The Jesuit Relations, which included many accounts of indigenous societies from scandalized missionaries. It seems that the notion of equality originally referred to equality between the sexes, and only later was extended to class relations.

Anyway, all this lead Europeans to rethink certain assumptions they had previously had, and lead directly to the French Revolution, with its famous slogan of Liberte, Equalite, Fraternite (Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood). It turns out that the idea of political equality can be traced back to equality of the sexes. This strikes me as highly significant. It suggests the possibility that class oppression grew out of gendered oppression.

Think about it. Women are, arguably, a class.

Now, to say this involves a departure from normal anarchist usage of that word, so let’s look at the definition of the word class.

By both the primary and secondary definition of the word, women qualify as a class of people. For our purposes, though, it is the secondary definition that is more important.

The truth is that women undeniably do have different social and economics statuses than men in every single human society that has ever been existed. This stems from the biological reality that male and female bodies are differentially adapted to different types of labour.

They have different social and economic statuses because biology determines, to a significant degree, what types of labour that male and females bodies are best suited to.

The gendered division of labor is a human universal

According to the anthropologist Richard Wrangham:

The sexual division of labor refers to women and men making different and complementary contributions to the household economy. Though the specific activities of each sex vary by culture, the gendered division of labor is a human universal. It is therefore assumed to have appeared well before modern humans started spreading across the globe sixty thousand to seventy thousand years ago.

Now, you probably already know what I’m referring to, but let me spell it out for you: men hunt and women cook.

If you’re offended by me saying this, you are offended by biology. I challenge you to find me an example of a society where gender roles are reversed - a society in which women hunt and men cook. No such society exists.

Although there are societies where women hunt and where men cook, there are no societies where women do more hunting than men, or where men do more cooking than women. It is simply more efficient to roll with biology than to oppose it on principle.

Wrangham writes of hunter-gatherers that:

Women and men spend their days seeking different kinds of foods, and the foods they obtain are eaten by both sexes. Why our species forages in such an unusual way (compared to primates and all other animals, whose adults do not share food with one another) has never been fully resolved.

Hunting large game was a predominantly masculine activity in 99.3% percent of recent societies.

Furthermore, the evidence that cooking is generally considered women’s work cross-culturally is extremely strong.

COOKING AS WOMEN’S WORK - A HUMAN UNIVERSAL?

That women tend to cook for their husbands is clear. In 1973 anthropologists George Murdock and Catarina Provost compiled the pattern of sex differences in fifty pro- ductive activities in 185 cultures. Although men often like to cook meat, overall cooking was the most female-biased activity of any, a little more so than preparing plant food and fetching water.

Women were predominantly or almost exclusively responsible for cooking in 97.8 percent of societies.

There are two ways to interpret this. The first is to conclude that women are the slaves of men. The other is to assume that male and female labour are complementary.

The difference is significant. Are men parasites living off of female labour? Or are men and women in a symbiotic relationship?

Might there be a few societies, not sampled by Murdock and Provost, in which women are so liberated that the gendered pattern of cooking is reversed?

Cultural anthropologist Maria Lepowsky studied the people of Vanatinai in the South Pacific expressly because, from the outside, this society seemed like a woman’s dream community.

In many ways, life was indeed very good for women. There was no ideology of male superiority. Both sexes could host feasts, lead canoeing expeditions, raise pigs, hunt, fish, participate in warfare, own and inherit land, decide about clearing land, make shell necklaces, and trade in such valued items as greenstone ax blades.

Women and men were equally capable of attaining the prestige of being “big” (important) people. Domestic violence was rare and strongly censured.

There was “tremendous overlap in the roles of men and women” and a great deal of personal control over how they chose to spend their time.

Women had “the same kinds of personal autonomy and control of the means of production as men.”

Yet despite the apparent escape from patriarchy, women on Vanatinai did all the domestic cooking.

Why is this?

Wrangham continues:

The classic reason suggested for this pattern is mutual convenience. Each sex gains from sharing their efforts, as many happily married couples can attest. But the explanation is superficial because it does not address the more fundamental problem of why our species has households at all, or the darker dynamic that sometimes has husbands exploiting Their wives’ labor. The men on Vanatinai could have shared the cooking easily, as the women would sometimes have liked them to do, but they chose not to. Charlotte Perkins Gilman noted that humans are the only species in which “the sex-relation is also an economic relation” and compared women’s role to that of horses. Molly and Eugene Christian complained that cooking “has made of woman a slave.”

Oh, snap. Shots fired. Okay, let’s do this.

ARE WOMEN SLAVES?

Personally, I disagree with the notion that a gendered division of labour, which is found in every single indigenous society, amounts to slavery.

There is a huge amount variability in gender relations in different societies, and I would probably agree in some cases that the status of women is so low that they are basically slaves, but I think that it is hyperbolic to state that the fact that cooking is almost universally considered women’s work means that females are effectively the slaves of males.

Remember, all traditional societies also require men to work. It’s not as if men are lounging about all day doing nothing.

Furthermore, men throughout history have often been conscripted into military service. They have often been forced to do backbreaking labour. They have often been worked to death. Modern feminists seem to think that men throughout history were all oppressors, which ignores the fact that civilization involves a hell of a lot of unfree male labour.

Now, I can easily imagine a feminist critique of this perspective - after all, the military men forcibly conscripting people tend to be men, not women. This is true, and certainly a valid point. I would argue, how ever, that the relevant factor here is class, not sex.

Think about it. Although men are almost always responsible for conducting the business of warfare, the beneficiaries of the spoils of the war would tend to be their family members, half of whom would presumably be female. Do you really think that the wives of Roman senators were complaining about their lives of luxury? Somehow I doubt it.

In the case of white feminism, this is particularly irksome, since the wealth of Europe for the past 500 years has largely come as a result of the brutal plunder of the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

White women now often see it as oppressive if their male spouses expect them to do housework. Indeed, white feminists often seem to prefer men willing to do domestic labour, and I suspect that the male partners of white feminists do more than their fair share of housework, although I doubt reliable research has been done on this subject.;\ Some feminists (such as Silvia Federici) feel strongly that women should receive wages for doing housework.

The situation has gotten ridiculous. If women expect to get paid for doing domestic chores, then why shouldn’t men? What world do feminists live in?

More importantly, why would a Marxist such as Federici wish to extender employer-employee relationships in the domestic sphere, the one area where the prevailing ethos is still one of non-commercialized reciprocity?

Now, don’t get me wrong. I definitely think that women are unfairly economically exploited in the modern world, and that ending that economic exploitation should be a central goal of anarchist revolutionaries. But feminists don’t seem to see the exploitation of male labour as a comparable problem. This is a problem, because feminist attitudes tend to undermine solidarity between men and women.

I won’t deny that there is an extra gendered dimension to the exploitation of female labour, and I understand very clearly why feminism exists. It came to be as part of the same cultural movement that involved anarchism and Romanticism.

Because men and women have significant biological and psychological differences, freedom looks somewhat different in the male and the female imaginations.

Feminism exists to ensure that women have their say, because women tend to have somewhat different ideas about what is desirable than men do.

If we are talking about freedom as a political concept, as opposed to the prerogative of individuals to do whatever they want, freedom is perhaps best thought of as a negotiated social consensus that involves a strong taboo against forcing others to do things against their will.

In reality, no society allows people to do whatever they want all the time. In practice, there are always competing social pressures involving different social conventions, customs, and taboos.

For all my critiques of feminism, I certainly do respect the work that many feminists do. For instance, I have the utmost admiration and respect for people who support survivors of domestic violence. I have done such work and I know how brutal it can be. My heart goes out to all those women who do such exhausting work for extended periods of time. I could not do that for long without burning out.

It is apparent to me that the world is run by men, although I will note that female psychopaths such as Hilary Clinton and Oprah Winfrey do make significant contributions to the system which rules over us.

My argument is this: We are ruled over by a parasitic ruling class that exploits both men and women by making it near-impossible to sustain a decent standard of living without participating in the wage-slavery system.

In other words, the matrix of entrapment is socioeconomic for both women and men, because the state seeks to insert itself into every area of society in order to extract the maximum amount of wealth possible.

The state makes people dependent upon it by design, and this is the true purpose of the welfare state.

The welfare state usurps the role of kinship structures in ensuring human survival, and modern people have therefore become alienated from the fact that human beings are social animals, meaning that our survival is not an individual matter, but a social one.

Aristotle hit the nail on the head when he said:

WHAT IS A FAIR DIVISION OF LABOUR?

Here’s my thesis - a gendered division of labour is an essential part of what makes us human, and it would be a fool’s errand to attempt to eliminate it.

Although technology has reduced the extent to which male physical strength guarantees a power imbalance between men and women, it is entirely impossible to eliminate the gendered division of labour for a very simple reason - men can’t have babies.

(Sorry to disappoint all you people who believe that humanity is on the cusp on transcending biology!)

The gendered division of labour is guaranteed by biology, and thankfully, there are plenty of women who acknowledge this.

I will say that I am all for bodily autonomy and I think that society should have a place for females who don’t want to become mothers. The fact remains, however, that most females will become mothers over the course of their lives.

Once a woman becomes a mother, she is dependent upon her kin. This is true is every culture. However, I think that it bears mentioning that men in traditional societies are equally dependent on their kin.

This leads us to a question that previous generations of humans don’t seem to have asked:

DOES DEPENDENCE EQUAL SLAVERY?

Some people, especially transhumanists, seem to see biology as a limiting factor to their freedom.

I suppose this makes some kind of sense. The fact that I am subject to the Law of Gravity means that I cannot fly. Strangely, though, I have never felt oppressed by the fact that I cannot fly.

This might sound cruel, but it’s true - if you feel oppressed by biology, the most logical form of rebellion would be to commit suicide.

Personally, I think that we, as anarchists, should accept that we, as human beings, are subject to certain natural laws, such as the fact that it is impossible to conceive a baby without male and female DNA, and that it is impossible to procreate without hosting the new life in a uterus. Human reproduction requires male and female cooperation.

Let me say that again:

Human reproduction requires male and female cooperation.

When I say that, I don’t just mean for conception or breast-feeding or child-rearing. I mean that every single part of the human life cycle involves male and female labour.

I reject the idea that women are doomed to a life of servitude by their biological dependence on men. This is the type of disingenuous feminist reasoning that too often goes unchallenged. Although it is true that women are dependent upon male labour, it is equally true that men are dependent upon female labour.

PARASITISM VERSUS SYMBIOSIS

Perhaps the metaphor of slavery isn’t appropriate when we are talking about biology. Perhaps a better dichotomy to use would be that of parasitism versus symbiosis.

Allow me to define both terms

PARASITE

parasite /păr′ə-sīt″/

noun

An organism that lives and feeds on or in an organism of a different species and causes harm to its host.

One who habitually takes advantage of the generosity of others without making any useful return.

One who lives off and flatters the rich; a sycophant.

SYMBIOSIS

symbiosis /sĭm″bē-ō′sĭs, -bī-/

noun

A close, prolonged association between two or more different organisms of different species that may, but does not necessarily, benefit each member.

A relationship of mutual benefit or dependence.

The living together in more or less imitative association or even close union of two dissimilar organisms.

Personally, I find it a lot more likely that men and women are evolved to a complex symbiosis that is based on the unique characteristics of the human species.

The idea that women are the slaves of men does not hold up when one considers the fact that male and female humans undeniably exist in a relationship of mutual dependence.

Feminists don’t seem to acknowledge that male labour kept females alive for thousands of generations. To be fair, it is equally true that female labour kept males alive. Because we are social animals, evolutionary success is not an individual matter. Survival of human societies is a social matter, and requires a symbiotic combination of male and female energy.

Furthermore, according to researchers, men actually tend to provide the majority of food calories in the majority of societies, especially in harsher environments.

Richard Wrangham explains:

It used to be thought that women typically produced most of the calories, as occurs among the Hadza [nomadic foragers of Tanzania]. Worldwide across foraging groups, however, men probably supplied the bulk of the food calories more often than women did. This is particularly true in the high, colder latitudes where there are few edible plants, and hunting is the main way to get food.

In an analysis of nine well-studied groups, the proportion of calories that came from foods collected by women ranged from a maximum of 57 percent, in the desert-living G/wi Bushmen of Namibia, down to a low of 16 percent in the Aché Indians of Paraguay. Women provided one-third of the calories in these societies, and men two-thirds.

Now, don’t get me wrong - I’m not saying that male labour is more valuable than female labour. There is significant variability in the relative value of male and female labour in food procurement seasonally and in different ecosystems. Furthermore, food procurement is only one of several tasks necessary to human survival.

Wrangham continues:

But such averages do not give an accurate sense of the value of items each sex contributes. At different times of year, the relative importance of foods obtained by women and men can change, and overall each sex’s foods can be just as critical as the other’s in maintaining health and survival. Furthermore, each sex makes vital contributions to the overall household economy regardless of any difference in the proportion of food calories contributed.

My argument is that men and women co-evolved to share parenting responsibilities, and that this explains the major biological differences between males and females of our species, as well as major cognitive difference between humans and the great apes.

WHAT’S THE DEAL WITH HUMANS?

Speaking of the difference between humans and apes, it should be noted that we are very different from our primate cousins.

Humans are often compared to chimpanzees and bonobos, our two closest relatives, but in reality we are very different from both of these species.

At some point in the future, I plan to talk about human sexuality, which is unique in the animal kingdom, but I’ll leave that aside for now.

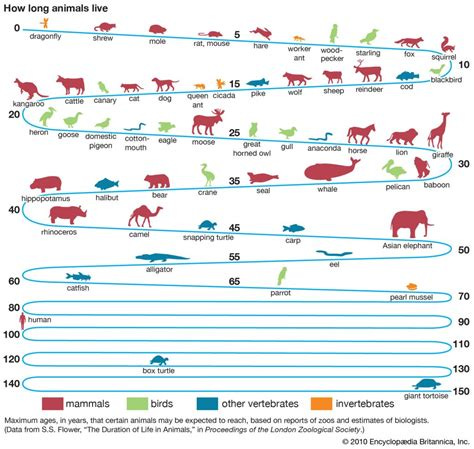

For now, let’s talk about the fact that human children take 12-15 years to reach maturity. That’s a long, long time. No other mammals take nearly so long to produce an adult specimen. Why is this?

The standard explanation for long childhoods is that it takes an extremely long time for human brains to develop.

Human beings take longer to reach sexual maturity than any other animal.

We also have a much longer life expectancy that other mammals.

I’ll mention here the sapiens in Homo Sapiens refers to our intelligence. What makes us human is our intelligence, which far exceeds that of our non-human relatives.

Basically, humans take much longer than other mammals to grow to maturity. Children therefore require a much greater amount of parental attention than other species.

This suggests that the basis of the sexual division of labour found cross-culturally is due to the fact that mothers and fathers learned to specialize in different yet complementary roles.

It is easy to speculate that human language might have begun due to the complex communication needs of mothers and fathers.

DID HUMANS INVENT LANGUAGE IN RESPONSE TO A BIOLOGICAL NEED? IF SO, WAS THAT NEED RELATED TO CO-PARENTING?

Language must have evolved in response to a biological need, or as a biological adaptation. Well, if children were dependent on the labour of two parents, and those parents lived in a nomadic hunting and gathering society, one can easily imagine how complex the communication needs of mother, father, and child must have been.

If this formed the basis for human language, then it follows that the basis for all politics is to be found in the mother-father-child child dynamic, as this would activate the most primal neuro-linguistic circuitry. Surprisingly, politics makes a lot of sense when you look at it this way. Don’t all tyrants seek to portray themselves as the Father of the Nation?

And here’s where things get really interesting - it turns out that the sexual division of labour is a major part of what made us human. Male and female bodies are specialized, meaning that they are adapted to different types of labour. This has a lot to do with the invention of cooking, which was made possible by the discovery of means to control fire.

As James C. Scott put it in his classic Against the Grain:

It is virtually impossible to exaggerate the importance of cooking in human evolution. The application of fire to raw food externalizes the digestive process; it gelatinizes starch and denatures protein.

The chemical disassembly of raw food, which in a chimpanzee requires a gut roughly three times the size of ours, allows Homo sapiens to eat far less food and expend far fewer calories extracting nutrition from it. The effects are enormous.

It allowed early man to gather and eat a far wider range of foods than before: plants with thorns, thick skins, and bark could be opened, peeled, and detoxified by cooking; hard seeds and fibrous foods that would not have repaid the caloric costs of digesting them became palatable; the flesh and guts of small birds and rodents could be sterilized.

Even before the advent of cooking, Homo sapiens was a broad-spectrum omnivore, pounding, grinding, mashing, fermenting, and pickling raw meat and plants, but with fire, the range of foods she could digest expanded exponentially.

In cooking, fire rendered a host of previously indigestible plants both palatable and more nutritious.

We owe our relatively large brain and relatively small gut (compared with other mammals, including primates), it is claimed, to the external predigestive help that cooking provides.

James C. Scott believes that the invention of cooking is a huge part of what made us human. Arguably, that means that harnessing the power of fire was the crucial innovation that led us to become the creatures we are today.

Cooking presumably started after some brave hominids were attracted by wildfire and learned to control it.

I think this moment interesting to think about, because it suggests that our proto-human ancestors were attracted to the fire by some combination of curiosity, daringness, and playfulness.

I think that we should create a myth in which the people who capture the first fire do so in the spirit of curiosity, playfulness, and wonder at the beauty of the fire.

I propose that we celebrate this moment in the New Anarchist Mythos we are creating. This was, after all, what made us human.

Think about that. The defining moment that made us human was a moment of curiosity, playfulness, and wonder. Those are three characteristics of humans that I happen to like quite a bit. I think this moment reflects well upon our species.

It is interesting to note that the Abrahamic religions do not mention how humans learned to control fire. Did Adam and Eve already possess knowledge of fire within the garden of Eden? Did they learn to control fire after being exiled? The story doesn’t say.

Could it be that control over fire was actually, metaphorically speaking, the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge? After all, gaining control of fire was presumably how we became a technological species. It was technology that caused us to gain the mastery over the natural world that we now possess, and the most important technological innovation in our history was the harnessing of fire, followed by the invention of projectile weapons. It was fire which allowed Man to become the most destructive species of Earthling. Could playing with fire have been the Original Sin that led to the Fall from Grace?

Probably not - it makes more sense to my mind that the forbidden fruit was some kind of hallucinogenic substance that caused significant alteration in human consciousness. But I think that harnessing the power of fire is one of the crucial event that made us human and therefore should be included in any human mythology. It seems surprising that the Bible neglects to mention this key event in world history.

Fire is not just important because it led to the invention of cooking - it also allows our proto-human ancestors to influence their environment.

It is because of fire that we became an engineer species. Perhaps this accounts for the peculiar dual nature of human beings.

We are, after all, both the most creative and the most destructive of all species.

Could this be because we owe our unique characteristics to the element of fire, which is also both creative and destructive?

I am reminded by the famous quote from Mikhail Bakunin.

DID FIRE MAKE US HUMAN?

Dr. Scott explains:

Fire, which we owe to our older relative Homo erectus, has been our great trump card, allowing us to resculpt the landscape so as to encourage food-bearing plants—nut and fruit trees, berry bushes— and to create browse that would attract desirable prey.

Elsewhere in the same book, he notes:

The case for the use of fire being the decisive transformation in the fortunes of hominids is convincing. It has been mankind’s oldest and greatest tool for reshaping the natural world. “Tool,” however, is not quite the right word; unlike an inanimate knife, fire has a life of its own. It is, at best, a “semi-domesticate,” appearing unbidden and, if not guarded carefully, escaping its shackles to become dangerously feral.

Hominids’ use of fire is historically deep and pervasive. Evidence for human fires is at least 400,000 years old, long before our species appeared on the scene. Thanks to hominids, much of the world’s flora and fauna consist of fire-adapted species (pyrophytes) that have been encouraged by burning. The effects of anthropogenic fire are so massive that they might be judged, in an evenhanded account of the human impact on the natural world, to overwhelm crop and livestock domestications. Why human fire as landscape architect doesn’t register as it ought to in our historical accounts is perhaps that its effects were spread over hundreds of millennia and were accomplished by “precivilized” peoples also known as “savages.” In our age of dynamite and bulldozers, it was a very slow-motion sort of environmental landscaping. But its aggregate effects were momentous.

Our ancestors could not have failed to notice how natural wildfires transformed the landscape: how they cleared old vegetation and encouraged a host of quick-colonizing grasses and shrubs, many bearing desired seeds, berries, fruits, and nuts. They could also not have failed to notice that a fire drove fleeing game from its path, exposed hidden burrows and nests of small game, and, most important, later stimulated the browse and mushrooms that attracted grazing prey. Native North Americans deployed fire to sculpt landscapes favored by elk, deer, beaver, hare, porcupine, ruffed grouse, turkey, and quail, all of which they hunted. The game they subsequently bagged represented a kind of harvesting of prey animals they had deliberately assembled by carefully creating a habitat they would find enticing. Quite apart from being the designers of hunting grounds—veritable game parks—early humans used fire to hunt large game. The evidence suggests that long before the bow and arrow appeared, roughly twenty thousand years ago, hominids were using fire to drive herd animals off precipices and to drive elephants into bogs where, immobilized, they could more easily be killed.

Fire was the key to humankind’s growing sway over the natural world—a species monopoly and trump card, worldwide. The Amazonian rain forest bears indelible traces of the use of fire to clear land and open the canopy; Australia’s eucalyptus landscape is, to a considerable degree, the effect of human fire. The volume of such landscaping in North America was such that when it stopped abruptly, due to the devastating epidemics that came with the European, the newly unchecked growth of forest cover created the illusion among white settlers that North America was a virtually untouched, primeval forest. […]

From our perspective, what this slow-motion landscape engineering accomplishes over time is to concentrate more subsistence resources in a smaller and smaller area. It rearranges, by a fire-assisted form of applied horticulture, desirable flora and fauna in a tighter ring around the camp(s) and makes hunting and forging easier. The radius of a meal, one might say, is reduced. Subsistence resources are closer at hand, more abundant, and more predictable. Wherever humans and fire were at work sculpting the landscape for hunting-and-gathering convenience, few nutrient-poor “climax” forests were allowed to develop.

This was the first and possibly most important impact that the discovery of fire had, but it was far from the only advantage it gave us.

FIRE GAVE US SUPERPOWERS

The advantages that fire provided included:

The ability to influence our environment in ways that had previously been impossible

The ability to eat new, previously undigestible types of food

The ability to metabolize food more effectively (because cooked food is easily to digest

Light

Heat

Defence against predators and enemies

A means of attacking predators and enemies (by burning their habitats)

There is a case to be made that fire is responsible for the fact that humans are the only hairless primate, as we evolved to become dependent on heat provided by fire. But I’ll leave that argument aside for now, because the invention of cooking strikes me as more important.

The primatologist Richard Wrangham in his 2009 book Catching Fire, credits Claude Levi-Strauss as the first to realize the importance of cooking to human evolution.

“Not only does cooking mark the transition from nature to culture,” Lévi-Strauss wrote in his influential book, The Raw and the Cooked, “but through it and by means of it, the human state can be defined with all its attributes.” Lévi- Strauss’s insight that cooking is a defining feature of humanity was perceptive.

It would be a Frenchman to figure that out, wouldn’t it?

I’ll quickly note that the invention of cooking occurred in our deep evolutionary past, long before we became human.

Wrangham explains:

Archaeologists are divided about the origins of cooking. Some suggest that fire was not regularly used for cooking until the Upper Paleolithic, about forty thousand years ago, a time when people were so modern that they were creating cave art. Others favor much earlier times, half a million years ago or before. A common proposal lies between those extremes, advocated especially by physical anthropologist Loring Brace, who has long noted that people definitely controlled fire by two hundred thousand years ago and argues that cooking started around the same time. As the wide range of views shows, the archaeological evidence is not definitive. Archaeology offers only one safe conclusion: it does not tell us what we want to know.

Thankfully, this does not mean that we are clueless. Wrangham continues:

The inability of the archaeological evidence to tell when humans first controlled fire directs us to biology, where we find two vital clues.

First, the fossil record presents a reasonably clear picture of the changes in human anatomy over the past two million years. It tells us what were the major changes in our ancestors’ anatomy, and when they happened.

Second, in response to a major change in diet, species tend to exhibit rapid and obvious changes in their anatomy. Animals are superbly adapted to their diets, and over evolutionary time the tight fit between food and anatomy is driven by food rather than by the animal’s characteristics.

Fleas do not suck blood because they happen to have a proboscis well de- signed for piercing mammalian skin; they have the proboscis because they are adapted to sucking blood. Horses do not eat grass because they happen to have the right kind of teeth and guts for doing so; they have tall teeth and long guts because they are adapted to eating grass.

Humans do not eat cooked food because we have the right kind of teeth and guts; rather, we have small teeth and short guts as a result of adapting to a cooked diet.

Therefore, we can identify when cooking began by searching the fossil record.

HOW COOKING CHANGED HUMAN ANATOMY

Zoologists often try to capture the essence of our species with such phrases as the naked, bipedal, or big-brained ape. They could equally well call us the small-mouthed ape.

The difference in mouth size is even more obvious when we take the lips into account. The amount of food a chimpanzee can hold in its mouth far exceeds what humans can do because, in addition to their wide gape and big mouths, chimpanzees have enormous and very muscular lips.

When eating juicy foods like fruits or meat, chimpanzees use their lips to hold a large wad of food in the outer part of their mouths and squeeze it hard against their teeth, which they may do repeatedly for many minutes before swallowing.

The strong lips are probably an adaptation for eating fruits, because fruit bats have similarly large and muscular lips that they use in the same way to squeeze fruit wads against their teeth. Humans have relatively tiny lips, appropriate for a small amount of food in the mouth at one time.

Our second digestive specialization is having weaker jaws. You can feel for yourself that our chewing muscles, the temporalis and masseter, are small. In nonhuman apes these muscles often reach all the way from the jaw to the top of the skull, where they sometimes attach to a ridge of bone called the sagittal crest, whose only function is to accommodate the jaw muscles. In humans, by contrast, our jaw muscles normally reach barely halfway up the side of our heads. If you clench and unclench your teeth and feel the side of your head, you have a good chance of being able to prove to yourself that you are not a gorilla: your temporalis muscle likely stops near the top of your ear.

We also have diminutive muscle fibers in our jaws, one-eighth the size of those in macaques. The cause of our weak jaws is a human-specific mutation in a gene responsible for producing the muscle protein myosin. Sometime around two and a half million years ago this gene, called MYH16, is thought to have spread throughout our ancestors and left our lineage with muscles that have subsequently been uniquely weak. Our small, weak jaw muscles are not adapted for chewing tough raw food, but they work well for soft, cooked food.

Human chewing teeth, or molars, also are small—the smallest of any primate species in relation to body size. Again, the predictable physical changes in food that are associated with cooking account readily for our weak chewing and small teeth. Even without genetic evolution, animals reared experimentally on soft diets develop smaller jaws and teeth…

Continuing farther into the body, our stomachs again are comparatively small. In humans the surface area of the stomach is less than one-third the size expected for a typical mammal of our body weight, and smaller than in 97 percent of other primates. The high caloric density of cooked food suggests that our stomachs can afford to be small. Great apes eat perhaps twice as much by weight per day as we do be- cause their foods are packed with indigestible fiber (around 30 percent by weight, compared to 5 percent to 10 percent or less in human diets). Thanks to the high caloric density of cooked food, we have modest needs that are adequately served by our small stomachs.

Below the stomach, the human small intestine is only a little smaller than expected from the size of our bodies, reflecting that this organ is the main site of digestion and absorption, and humans have the same basal metabolic rate as other primates in relation to body weight. But the large intestine, or colon, is less than percent of the mass that would be expected for a primate of our body weight. The colon is where our intestinal flora ferment plant fiber, pro- ducing fatty acids that are absorbed into the body and used for energy. That the colon is relatively small in humans means we cannot retain as much fiber as the great apes can and therefore cannot utilize plant fiber as effectively for food. But that matters little. The high caloric density of cooked food means that normally we do not need the large fermenting potential that apes rely on.

Finally, the volume of the entire human gut, comprising stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, is also relatively small, less than in any other primate measured so far. The weight of our guts is estimated at about 60 percent of what is expected for a primate of our size: the human digestive system as a whole is much smaller than would be predicted on the basis of size relations in primates.

Our small mouths, teeth, and guts fit well with the softness, high caloric density, low fiber content, and high digestibility of cooked food. The reduction increases efficiency and saves us from wasting unnecessary metabolic costs on features whose only purpose would be to allow us to digest large amounts of high-fiber food. Mouths and teeth do not need to be large to chew soft, high-density food, and a reduction in the size of jaw muscles may help us produce the low forces appropriate to eating a cooked diet. The smaller scale may reduce tooth damage and subsequent disease. In the case of intestines, physical anthropologists Leslie Aiello and Peter Wheeler reported that compared to that of great apes, the reduction in human gut size saves humans at least 10 percent of daily energy expenditure: the more gut tissue in the body, the more energy must be spent on its metabolism. Thanks to cooking, very high-fiber food of a type eaten by great apes is no longer a useful part of our diet. The suite of changes in the human digestive system makes sense.

Richard Wrangham persuasively argues that the evolutionary advantages of cooking, made possible by fire, is what led to the sexual division of labour, which in term caused us to become anatomically modern humans. It’s a fascinating hypothesis, because it suggests that the basis for human social behaviour, including language and politics, can be traced back to the mutual interdependence of parents for the purposes of child-rearing. To my mind, this seems so reasonable that I’m surprised I’m only encountering this idea at 36 years old. Keep in mind I’m taken an interest in politics from the time I was a small child.

In theory, among hunter-gatherers both males and females could forage for themselves, like every other animal, and then cook his or her own meal at the end of the day.

So what led to a sexual division of labor in which men routinely insist that it is women’s lot to do the household cooking?

Nonhuman primates mostly pick and eat their food at once. But hunter-gatherers bring food to a camp for processing and cooking, and in the camp, labor can be offered and exchanged.

This suggests that cooking might be responsible for converting individual foraging into a social economy. Archaeologist Catherine Perlès thinks so: “The culinary act is from the start a project. Cooking ends individual self- sufficiency.”

Relying on cooking creates foods that can be owned, given, or stolen. Before cooking, we ate more like chimpanzees, everyone for themselves. After the advent of cooking, we assembled around the fire and shared the labor.

Perlès’s notion that, by necessity, cooking was a social activity is supported by Dutch sociologist and fire expert Joop Goudsblom, who suggests that cooking required social coordination,“if only to ensure that there would always be someone to look after the fire.”

Food historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto proposed that cooking created meal- times and thereby organized people into a community. For culinary historian Michael Symons, cooking promoted cooperation through sharing, because the cook always distributes food.

Cooking, he wrote, is “the starting-place of trades.”

These ideas fit nicely with the ubiquitous social importance of cooked food. The contrast between communal and solitary eating is particularly pronounced among hunter- gatherers, for whom cooking is a highly social act, unlike eating raw food.

When people are out of camp, their snacks tend to be raw foods such as ripe fruits or grubs, and these are normally collected individually and eaten without sharing. But when people cook food, they do so mostly in camp, and they share it within the family or, when feasting, with other families. Furthermore, much of the labor in preparing the meal is complementary.

In a common pattern, a woman brings firewood and vegetables, prepares the vegetables, and does the cooking. A man brings meat, which either he or a woman might cook. Family members also tend to eat at roughly the same time (though the man may eat first) and often sit face to face around a fire.

It is noteworthy that, in this theory, reciprocal sharing of both goods and services is the basis of human politics. This supports the idea that the natural form of political organization that we are evolved for would be based on reciprocal sharing, also known as “primitive communism”.

Interestingly, this primitive communism seems to suggest gender egalitarianism, as women would have had a considerable degree of bargaining power in societies that were wholly dependent upon their labour.

Voluntary cooperation between men and women would simply be easier than men tyrannizing women, and if it was mutually understood that voluntary male-female cooperation was the best available survival strategy, it seems likely to have been accepted by all members of a given society (or at least most of them).

Despite what modern feminists would have you believe, women have a considerable amount of political power in traditional societies because men are dependent upon them.

Wrangham writes:

Inequitable as marriage is in certain respects for hunter-gatherer women, that women have to cook for men empowers them. “Her economic skill is not only a weapon for subsistence, but also a means of enforcing good treatment and justice,” wrote Phyllis Kaberry of Australian aboriginal women.

A wife who cooks badly might be beaten, shouted at, chased, or have her possessions broken, but she can respond to abuse by refusing to cook or threatening to leave.

Such disputes seem to be characteristic mostly of new marriages. Most couples easily develop a comfortable predictability, with wives doing their best to provide husbands their cooked meals and husbands appreciating the effort.

Hunter-gatherer women are therefore not normally treated badly, and many ethnographers have concluded that, in comparison to most societies, married women lead lives of high status and considerable autonomy.

It is noteworthy that other primates do not share food or have any comparable gendered division of labour.

Hints of comparable sex differences in food procurement have been detected in primates. Female lemurs tend to eat more of the preferred foods than males. In various monkeys such as macaques, guenons, and mangabeys, females eat more insects and males eat more fruit. Among chimpanzees, females eat more termites and ants, and males eat more meat. But such differences are minor because in every non-human primate the overwhelming majority of the foods collected and eaten by females and males are the same types.

Even more distinctive of humans is that each sex eats not only from the food items they have collected themselves, but also from their partner’s finds. Not even a hint of this complementarity is found among nonhuman primates. Plenty of primates, such as gibbons and gorillas, have family groups. Females and males in those species spend all day together, are nice to each other, and bring up their offspring together, but, unlike people, the adults never give each other food. Human couples, by contrast, are expected to do so.

It is noteworthy that something like pair-bonded heterosexual marriage is a nearly-universal human institution, although marriage conventions differ widely across cultures. Interestingly, this often seems to have as much to do with food as it does with sex.

In foraging societies a woman always shares her food with her husband and children, and she gives little to anyone other than close kin. Men likewise share with their wives, whether they have received meat from other men or have brought it to camp themselves and shared part of it with other men. The exchanges between wife and husband permeate families in every society. The contributions might involve women digging roots and men hunting meat in one culture, or women shopping and men earning a salary in another. No matter the specific items each partner contributes, human families are unique compared to the social arrangements of other species because each household is a little economy.

Elsewhere, he suggests:

The sex difference suggests that the cultural rules that specify how women’s and men’s foods are to be shared are adapted to the society’s need to regulate competition specifically over food. The rules were not merely the result of a general moral attitude.

In other words, human cultures developed over countless generations as ways of adaptation to specific environments. Culture is sculpted by evolutionary pressures to optimize the likelihood of survival.

Because food is massively important to survival, traditional societies include customs regarding food at a very primal level of their cultures, including marriage conventions.

A woman’s right to ownership protects her from supplicants of both sexes. In Australia’s western desert, a hungry aborigine woman can sit amicably by a cook’s fire, but she will not receive any food unless she can justify it by invoking a specific kinship role. It is even more difficult for a man.

A bachelor or married man who approaches someone else’s wife in search of food would be in flagrant breach of convention and an immediate cause of gossip, just as a woman would be if she gave him any food. The norm is so strong that a wife’s presence at a meal can protect even a husband from being approached.

Among Mbuti Pygmies, if a family is eating together by their hearth, they will be undisturbed. But when a man is eating alone, he is likely to attract his friends, who will expect to share his food.

Under this system, an unmarried woman who offers food to a man is effectively flirting, if not offering betrothal. Male anthropologists have to be aware of this to avoid embarrassment in such societies.

Co-feeding is often the only marriage ceremony, such that if an unmarried pair are seen eating together, they are henceforward regarded as married.

In New Guinea, Bonerif hunter-gatherers rely on the sago palm tree for their staple food year-round. If a woman prepares her own sago meal and gives it to a man, she is considered wed to him. The interaction is public, so others take the opportunity to tease the new couple with jokes equating food and sex, such as, “If you get a lot of sago you are going to be a happy man.” The association is so ingrained that a man’s penis is symbolized by the sago fork with which he eats his meal. If a man takes his sago fork out of his hair and shows it to a woman, they both know he is inviting her for sex. In that society, for a woman to even look at a man’s feeding implement is to break the rule against her constrained food-sharing.

Because interactions occur in public, a husband’s presence is not necessary to maintain customary principles. The husband’s role is important not so much for his physical presence, but because he represents a reliable conduit to the support of the community. If a wife reported to her husband that another man had inappropriately asked her for food, the accused would be obliged to defend himself to both the husband and the community at large.

My argument is this - the sexual division of labour made us human, and any genuine quest to understand human nature should not neglect this fact.

Specialization of labor also increases productivity by allowing women and men to become more skilled at their particular tasks, which promotes efficient use of time and resources. It is even thought to be associated with the evolution of some emotional and intellectual skills, because our reliance on sharing requires a cooperative temperament and exceptional intelligence.

For such reasons anthropologists Jane and Chet Lancaster described the sexual division of labor as the “fundamental platform of behavior for the genus Homo,” and the “true watershed for differentiating ape from human lifeways.”

The classic explanation in physical anthropology for this social structure is essentially what Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin proposed: when meat became an important part of the human diet, it was harder for females than males to obtain. Males with a surplus would have offered some to females, who would have appreciated the gift and returned the favor by gathering plant foods to share with males. The result was an incipient household.

Wrangham quotes a physical anthropologist named Sherwood Washburn, who put it this way:

When males hunt and females gather, the results are shared and given to the young, and the habitual sharing between a male, a female, and their offspring becomes the basis for the human family. According to this view, the human family is the result of the reciprocity of hunting, the addition of a male to the mother-plus-young social group of the monkeys and apes.

I will end in the spirit of David Graeber, by suggesting that the basis for social peace, which has always been the goal of anarchist revolutionaries, is to be found in “a recognition of our ultimate interdependence”.

Wrangham mentions that an unmarried man in hunter-gatherer societies would tend to be an unhappy, hungry man.

Hunter-gatherer men suffered if they had no wives or female relatives to provide cooked meals. “An aborigine of this Colony without a female partner is a poor dejected being,” wrote G. Robinson about the Tasmanians in 1846.

When an Australian aboriginal wife deserts her husband, wrote Phyllis Kaberry, he can easily replace her role as a sexual partner but he suffers because he has lost someone attending to his hearth.

The loss is important because a bachelor is a sorry creature in subsistence societies, particularly if he has no close kin.

As Thomas Gregor explained for the Mehinaku hunter-gardeners of Brazil, an unmarried man “cannot provide the bread and porridge that is the spirit’s food and a chief ’s hospitality. . . . To his friends, he is an object of pity.” […]

Colin Turnbull explained precisely why bachelors among Mbuti Pygmies were unhappy: “A woman is more than a mere producer of wealth; she is an essential partner in the economy. Without a wife a man cannot hunt; he has no hearth; he has nobody to build his house, gather fruits and vegetables and cook for him.”

Examples like these are so widespread that according to Jane Collier and Michelle Rosaldo, in small-scale societies all men have a “strictly economic need for a wife and hearth.”

There you have it. Men and women depend upon each other for survival. Not exactly a radical claim, is it?

What do you think? Should humanity attempt to eliminate the sexual division of labour? Or should we negotiate a fair division of labour in which men and women do different and complementary forms of labour?

I hope you have enjoyed this article, and I look forward to hearing your thoughts in the comment section.

Love & Solidarity,

Crow Qu’appelle

Like everything else, the pendulum swung wide to either side. We need a balance point.

"Are women slaves?"

Which women, where and when?

Is Taylor Swift a slave?