How Occupy Wall Street Began

A History Lesson on the 13th Anniversary of the Occupation of Zuccotti Park

Hey Folks,

Today is the 13th anniversary of the day that the #OccupyWallStreet movement began.

Although it is fondly remembered by some, it is now largely seen as a failure. I don’t necessarily disagree with this assessment, but nevertheless, I think it is well worth reflecting upon. It might not be particularly fun, but I think it is important.

Eventually, people will return to the streets to protest government corruption again, and if we don’t learn from our mistakes, we will repeat them.

I also happen to think that the Occupy Movement was more important than most people think it was.

I think that the Powers That Shouldn’t Be launched a major campaign of psychological warfare which succeeded in polarizing American society and completely destroying the U.S. Left.

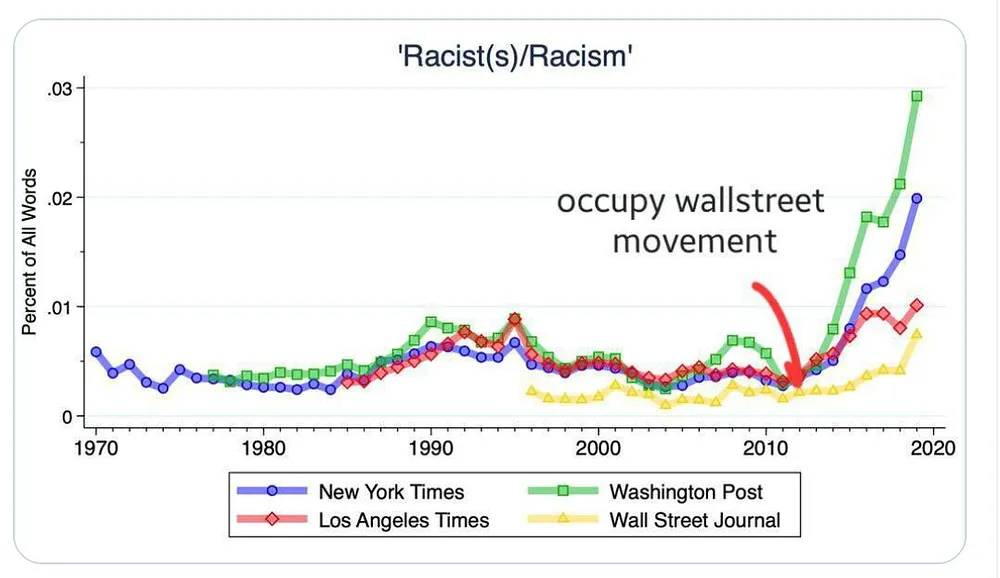

The Occupy Movement was the last big Leftist social movement which foregrounded class. All the subsequent ones have focused on race and gender. I don’t think this is coincidental. I think that activist energy was diverted into dead ends, and that this was by design.

Check out these charts, for instance:

I will flesh out my hypothesis further in future posts, but today I just want to share with you the story of how the Occupy movement began. It is an excerpt from David Graeber’s The Democracy Project.

One important thing I think many people have forgotten about is that the Occupy Movement followed hot on the heels of the Arab Spring, the wave of popular revolts throughout the Middle East that began soon after the financial crash of 2008.

If you ask me, our rulers launched a a major class war against us in early 2012 in response to the Occupy Movement, which. We’re still living with the consequences of that counter-revolution, which I think has included many manifestations, including #MeToo, the Proud Boys, Antifa, and the (s)election of Donald Trump.

Yeah, yeah, I know, I’m a crazy conspiracy theorist. I don’t expect you to adopt my point of view. But try it on for size. You might just find that things make a surprising amount of sense when you looking at the world through this lens.

Let’s recall the words of Aristotle: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.”

Words to live by.

Solidarity,

Crow Qu’appelle

P.S. And if Occupy wasn’t important, why did they make a Batman movie about it?

THE BEGINNING IS NEAR

In March 2011, Micah White, editor of the Canadian magazine Adbusters, asked me to write a column on the possibility of a revolutionary movement springing up in Europe or America. At the time, the best I could think to say was that when a true revolutionary movement arises, everyone, the organizers included, is taken by surprise. I had recently had a long conversation with an Egyptian anarchist named Dina Makram-Ebeid to that effect, at the height of the uprising in Tahrir Square, which I used to open the column.

“The funny thing is,” my Egyptian friend told me, “you’ve been doing this so long, you kind of forget that you can win. All these years, we’ve been organizing marches, rallies… And if only 45 people show up, you’re depressed. If you get 300, you’re happy. Then one day, you get 500,000. And you’re incredulous: on some level, you’d given up thinking that could even happen.”

Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt was one of the most repressive societies on earth—the entire apparatus of the state was organized around ensuring that what ended up happening could never happen. And yet, it did.

So why not here?

To be honest, most activists I know go around feeling much like my Egyptian friend used to feel—we organize much of our lives around the possibility of something that we’re not sure we believe could ever really happen.

And then it did.

Of course, in our case, it wasn’t the fall of a military dictatorship but the outbreak of a mass movement based on direct democracy—an outcome, in its own way, just as long dreamed of by its organizers, just as long dreaded by those who held ultimate power in the country, and just as uncertain in its outcome as the overthrow of Mubarak had been.

The story of this movement has been told in countless outlets already, from the Occupy Wall Street Journal to the actual Wall Street Journal, with varying motives, points of view, casts of characters, and degrees of accuracy. In most, my own importance has been vastly overstated. My role was that of a bridge between camps. But my aim in this chapter is not so much to set the historical record straight, or even to write a history at all, but rather to give a sense of what living at the fulcrum of such a historical convergence can be like. Much of our political culture, even daily existence, makes us feel that such events are simply impossible (indeed, there is reason to believe that our political culture is designed to make us feel that way). The result has a chilling effect on the imagination. Even those who, like Dina or myself, organized much of our lives—and most of our fantasies and aspirations—around the possibility of such outbreaks of the imagination were startled when such an outbreak actually began to happen.

This is why it’s crucial to underline that transformative outbreaks of imagination have happened, are happening, and surely will continue to happen again. The experience of those who live through such events is to find our horizons thrown open; to find ourselves wondering what else we assume cannot really happen actually can. Such events cause us to reconsider everything we thought we knew about the past. This is why those in power do their best to bottle them up, to treat these outbreaks of imagination as peculiar anomalies, rather than the kind of moments from which everything, including their own power, originally emerged. So, telling the story of Occupy—even if from just one actor’s point of view—is important. It’s only in the light of the sense of possibility that Occupy opened up that everything else I have to say makes sense.

When I wrote the piece for Adbusters—the editors gave it the title “Awaiting the Magic Spark”—I was living in London, teaching anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London, in my fourth year of exile from U.S. academia. I had been fairly deeply involved with the U.K. student movement that year, visiting many of the dozens of university occupations across the country that had formed to protest the Conservative government’s broadside assault on the British public education system, taking part in organizing and street actions. Adbusters specifically commissioned me to write a piece speculating on the possibility that the student movement might mark the beginning of a broad, Europe-wide, or even worldwide, rebellion.

I had long been a fan of Adbusters, but had only fairly recently become a contributor. I was more a street-action person when I wasn’t being a social theorist. Adbusters, on the other hand, was a magazine for “culture jammers.” It was originally created by rebellious advertising workers who loathed their industry and decided to join the other side, using their professional skills to subvert the corporate world they had been trained to promote. They were most famous for creating “subvertisements,” anti-ads—for instance, fashion ads featuring bulimic models vomiting into toilets—with professional production values, and then trying to place them in mainstream publications or on network television (attempts that were inevitably refused). Of all radical magazines, Adbusters was easily the most beautiful, but many anarchists considered their stylish, ironic approach distinctly less than hard-core. I had first started writing for them when Micah White contacted me back in 2008 to contribute a column. Over the summer of 2011, he had become interested in making me into something like a regular British correspondent.

Such plans were thrown askew when a year’s leave took me back to America. I arrived that July, the summer of 2011, in my native New York, expecting to spend most of the summer touring and doing interviews for a recently released book on the history of debt. I also wanted to plug back into the New York activist scene, but with some hesitation, since I had the distinct impression that the scene was in something of a shambles.

I had first gotten heavily involved in activism in New York between 2000 and 2003, the heyday of the Global Justice Movement. That movement, which began with the Zapatista revolt in Mexico’s Chiapas in 1994 and reached the United States with the mass actions that shut down the World Trade Organization meetings in Seattle in 1999, was the last time any of my friends had a sense that some sort of global revolutionary movement might be taking shape. Those were heady days. In the wake of Seattle, it seemed every day there was something going on: a protest, an action, a Reclaim the Streets or activist subway party, and a thousand different planning meetings. But the ramifications of 9/11 hit us very hard, even if they took a few years to have their full effect. The level of arbitrary violence police were willing to employ against activists ratcheted up unimaginably; when a handful of unarmed students occupied the roof of the New School in a protest in 2009, for instance, the NYPD is said to have responded with four different anti-terrorist squads, including commandos rappelling off helicopters armed with all sorts of peculiar sci-fi weaponry.

And the scale of the anti-war and anti–Republican National Convention protests in New York ironically sapped some of the life out of the protest scene: anarchist-style “horizontal” groups, based on principles of direct democracy, had come to be largely displaced by vast top-down anti-war coalitions for whom political action was largely a matter of marching around with signs. Meanwhile, the New York anarchist scene, which had been at the very core of the Global Justice Movement, wracked by endless personal squabbles, had been reduced largely to organizing an annual book fair.

April 6, it became apparent, was by no means a radical group. Rashed, for example, worked for a bank. By disposition, the two representatives of the movement were classic liberals, the sort of people who, had they been born in America, would have been defenders of Barack Obama. Yet here they were, sneaking away from their minders to address a motley collection of anarchists and Marxists—who, they had come to realize, were their American counterparts.

“When they were firing tear gas canisters straight into the crowd, we looked at those tear gas canisters, and we noticed something,” Rashed told us. “Every one said, ‘Made in USA.’ So, we later found out, was the equipment used to torture us when we were arrested. You don’t forget something like that.”

After the formal talk, Maher and Rashed wanted to see the Hudson River, which was just across the highway, so six or seven of the more intrepid of us darted across the traffic of the West Side Highway and found a spot by a deserted pier. I used a flash drive I had on me to copy some videos Rashed wanted to give us, some Egyptian, and some, curiously, produced by the Serbian student group Otpor!—which had played probably the most important role in organizing the mass protests and various forms of nonviolent resistance that had overthrown the regime of Slobodan Milosevic in late 2000. The Serbian group, he explained, had been one of the primary inspirations for April 6. The Egyptian group’s founders had not only corresponded with Otpor! veterans, many had even flown to Belgrade in the organization’s early days to attend seminars on techniques of nonviolent resistance. April 6 even adopted a version of Otpor!’s raised-fist logo.

“You do realize,” I said to him, “that Otpor! was originally set up by the CIA?”

He shrugged. Apparently, the origin of the Serbian group was a matter of complete indifference to him.

But Otpor!’s origins were even more complicated than that. In fact, several of us hastened to explain, the tactics that Otpor! and many other groups in the vanguard of the “colored” revolutions of the 2000s—from the old Soviet empire down to the Balkans—implemented, with help from the CIA, were the ones the CIA originally learned from studying the Global Justice Movement, including tactics executed by some of the people who were gathered on the Hudson River that very night.

It’s impossible for activists to really know what the other side is thinking. We can’t even really know exactly who the other side is: who’s monitoring us, who, if anyone, is coordinating international security efforts against us. But you can’t help but speculate. And it was difficult not to notice that back around 1999, right around the time that a loose global network of antiauthoritarian collectives began mobilizing to shut down trade summits from Prague to Cancun using surprisingly effective techniques of decentralized direct democracy and nonviolent civil disobedience, certain elements in the U.S. security apparatus began not only studying the phenomenon but trying to see if they could foster such movements themselves.

This kind of turnabout was not unprecedented: in the 1980s, the CIA had done something similar, using the fruits of 1960s and 1970s counterinsurgency research into how guerrilla armies worked to try to manufacture insurgencies like the Contras in Nicaragua. Something like that seemed to be happening again. Government money began pouring into international foundations promoting nonviolent tactics, and American trainers—some veterans of the antinuclear movement of the 1970s—were helping organize groups like Otpor!

It’s important not to overstate the effectiveness of such efforts. The CIA can’t produce a movement out of nothing. Their efforts proved effective in Serbia and Georgia but failed completely in Venezuela. But the real historical irony is that it was these techniques, pioneered by the Global Justice Movement, and successfully spread across the world by the CIA to American-aided groups, that in turn inspired movements that overthrew American client states. It’s a sign of the power of democratic direct action tactics that once they were let loose into the world, they became uncontrollable.

US Uncut

For me, the most concrete thing that came out of that evening with the Egyptians was that I met Marisa. Five years before, she had been one of the student activists who’d made a brilliant—if ultimately short-lived—attempt to re-create the 1960s activist group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Most New York activists still referred to the key organizers as “those SDS kids”—but, while most of them were at this point trapped working fifty to sixty hours a week paying off their student loan debts, Marisa, who had been in an Ohio branch of SDS and only later moved to the city, was still very much active. Indeed, she seemed to have a finger in almost everything worthwhile that was still happening in the New York activist scene.

Marisa is one of those people one is almost guaranteed to underestimate: small, unassuming, with a tendency to fold herself into a ball and all but disappear in public events. But she is one of the most gifted activists I’ve ever met. As I was later to discover, she had an almost uncanny ability to instantly assess a situation and figure out what’s happening, what’s important, and what needs to be done.

As the little meeting along the Hudson broke up, Marisa told me about a meeting the next day at EarthMatters in the East Village for a new group she was working with called US Uncut—inspired, she explained, by the British coalition UK Uncut, which had been created to organize mass civil disobedience against the Tory government’s austerity plans in 2010. They were mostly pretty liberal, she hastened to warn me, not many anarchists, but in a way that was what was so charming about the group: the New York chapter was made up of people of all sorts of different backgrounds—“real people, not activist types”—middle-aged housewives, postal workers. “But they’re all really enthusiastic about the idea of doing direct action.”

The idea had a certain appeal. I’d never had a chance to work with UK Uncut when I was in London, but I had certainly run across them.

The tactical strategy of UK Uncut was simple and brilliant. One of the great scandals of the Conservative government’s 2010 austerity package was that at the same time as they were trumpeting the need to triple student fees, close youth centers, and slash benefits to pensioners and people with disabilities to make up for what they described as a crippling budget shortfall, they exhibited absolutely no interest in collecting untold billions of pounds sterling of back taxes owed by some of their largest corporate campaign contributors—revenue that, if collected, would make most of those cuts completely unnecessary. UK Uncut’s way of dramatizing the issue was to say: fine, if you’re going to close our schools and clinics because you don’t want to take the money from banks like HSBC or companies like Vodafone, we’re just going to conduct classes and give medical treatment in their lobbies. UK Uncut’s most dramatic action had taken place on the 26th of March, only a few weeks before my return to New York, when, in the wake of a half-million-strong labor march in London to protest the cuts, about 250 activists had occupied the ultra-swanky department store Fortnum & Mason.

Fortnum & Mason was mainly famous for selling the world’s most expensive tea and biscuits; their business was booming despite the recession, but their owners had also somehow managed to avoid paying £40 million in taxes.

At the time, I was working with a different group, Arts Against Cuts, mainly made up of women artists, whose primary contribution on the day of the march was to provide hundreds of paint bombs to student activists geared up in black hoodies, balaclavas, and bandanas (in activist language, in “Black Bloc”). I had never actually seen a paint bomb before. When some of my friends started opening up their backpacks, I remember being impressed by how small they were. The paint bombs weren’t actual bombs, just tiny water balloons of the same shape and slightly larger than an egg, half full of water, half full of different colors of water-soluble paint. The nice thing was that one could throw them like baseballs at almost any target—an offending storefront, a passing Rolls or Lamborghini, a riot cop—and they would make an immediate and dramatic impression, splashing primary colors all over the place, but in such a way that we never ran the remotest danger of doing anyone any physical harm.

The plan that day was for the students and their allies to break off from the labor march at three o’clock in small groups and fan out through London’s central shopping area, blockading intersections and decorating the marquees of notable tax evaders with paint bombs. After about an hour, we heard about the UK Uncut occupation of Fortnum & Mason and we trickled down to see if we could do anything to help. I arrived just as riot cops were sealing off the entryways and the last occupiers who didn’t want to risk arrest were preparing to jump off the department store’s vast marquee into the arms of surrounding protesters. The Black Bloc assembled, and after unleashing our few remaining balloons, we linked arms to hold off an advancing line of riot cops trying to clear the street so they could begin mass arrests. A few weeks later, in New York, my legs were still etched with welts and scrapes from being kicked in the shins on that occasion. (I remember thinking at the time that I now understood why ancient warriors wore greaves—if there are two opposing lines of shield-bearing warriors facing each other, the most obvious thing to do is to kick your opponent in the shins.)

Autonomist Theory Seminar

Colleen had urged me to come down that Sunday if I wanted to get a sense of what was happening in New York. I’d agreed, then kind of half-forgotten, since I was spending that morning with a British archaeologist friend passing through town for a conference. We’d both become engrossed in exploring midtown comic book emporia, trying to find appropriate presents for his kids. Around 12:30, I received a text message from Colleen:

C: You coming to this 16 Beaver thing?

D: Where is it again? I’ll go.

C: Now till 5 though, so if you come later, there will still be talking.

D: I’ll head down.

C: Sweet!

D: Remind me what they’re even talking about.

C: A little bit of everything.

The purpose of the meeting was to have presentations about various anti-austerity movements growing around the world—in Greece, Spain, and elsewhere—and to end with an open discussion about how to bring a similar movement here.

I arrived late. By the time I got there, I’d already missed the discussion of Greece and Spain but was surprised to see so many familiar faces in the room. The Greek talk had been given by an old friend, an artist named Georgia Sagri. As I walked in, an even older friend, Sabu Kohso, was in the middle of a talk about antinuclear mobilizations in the wake of the Fukushima meltdown in Japan. The only discussion I caught all the way through was the very last talk, about New York, and it was very much an anticlimax. The presenter was Doug Singsen, a soft-spoken art historian from Brooklyn College, who told the story of the New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts Coalition, which had sponsored a small sidewalk camp they called Bloombergville, named after Mayor Michael Bloomberg, opposite City Hall in lower Manhattan.

In some ways, it was a tale of frustration. The coalition had started out as a broad alliance of New York unions and community groups, with the express purpose of sponsoring civil disobedience against Bloomberg’s draconian austerity budgets. This was unusual in itself: normally, union officials balk at the very mention of civil disobedience—or, at least, any civil disobedience that is not of the most completely scripted, prearranged sort (for instance, arranging with the police in advance when and how activists are to be arrested). This time, unions like the United Federation of Teachers played an active role in planning the camp, inspired in part by the success of similar protest encampments in Cairo, Athens, and Barcelona—but then got cold feet and pulled out the moment the camp was actually set up. Nonetheless, forty or fifty dedicated activists, mostly socialists and anarchists, stuck it out for roughly four weeks, from mid-June to early July. With numbers that small, and no real media attention or political allies, acting in defiance of the law was out of the question, since everyone would just be arrested immediately and no one would ever know. But they had the advantage of an obscure regulation in New York law whereby it was not illegal to sleep on the sidewalk as a form of political protest, provided one left a lane open to traffic and didn’t raise anything that could be described as a “structure” (such as a lean-to or tent). Of course, without tents or any sort of structure, it was hard to describe the result as really being a “camp.” The organizers had done their best to liaise with the police, but they weren’t in a particularly strong position to negotiate. They ended up being pushed farther and farther from City Hall before dispersing altogether.

The real reason the coalition fragmented so quickly, Singsen explained, was politics. The unions and most of the community groups were working with allies on the City Council, who were busy negotiating a compromise budget with the mayor.

“It soon became apparent,” he said, “that there were two positions: the moderates, who were willing to accept the need for some cuts, thinking it would place them in a better negotiating position to limit the damage, and the radicals—the Bloombergville camp—who rejected the need for any cuts at all.” Once a deal seemed in sight, all support for civil disobedience, even in its mildest form, disappeared.

Three hours later, Sabu, Georgia, Colleen, a couple of the student organizers from Bloombergville, and I were nursing our beers a few blocks away and trying to hash out what we thought of all of this. It was a particular pleasure to see Georgia again. The last time we’d met had been in Exarchia, a neighborhood in Athens full of squatted social centers, occupied parks, and anarchist cafés, where we’d spent a long night downing glasses of ouzo at street corner cafés while arguing about the radical implications of Plato’s theory of agape, or universal love—conversations periodically interrupted by battalions of riot police who would march through the area all night long to make sure no one ever felt comfortable. Colleen explained this was typical of Exarchia. Occasionally, she told us, especially if a policeman had recently been injured in a clash with protesters, the police would choose one café, thrash everyone in sight, and destroy the cappuccino machines.

Back in New York, it wasn’t long before the conversation turned to what it would take to startle the New York activist scene out of its doldrums.

“The main thing that stuck in my head about the talk about Bloombergville,” I volunteered, “was when the speaker was saying that the moderates were willing to accept some cuts, and the radicals rejected cuts entirely. I was just following along nodding my head, and suddenly I realized: wait a minute! What is this guy saying here? How did we get to a point where the radical position is to keep things exactly the way they are?”

The Uncut protests and the twenty-odd student occupations in England that year had fallen into the same trap. They were militant enough, sure: students had trashed Tory headquarters and ambushed members of the royal family. But they weren’t radical. If anything, the message was reactionary: stop the cuts! What, and go back to the lost paradise of 2009? Or even 1959, or 1979?

“And to be perfectly honest,” I added. “It feels a bit unsettling watching a bunch of anarchists in masks outside Topshop, lobbing paint bombs over a line of riot cops, shouting, ‘Pay your taxes!’ ” (Of course, I had been one of those radicals with paint bombs.)

Was there some way to break out of the trap? Georgia was excited by a campaign she’d seen advertised in Adbusters called “Occupy Wall Street.” When Georgia described the ad to me, I was skeptical. It wouldn’t be the first time someone had tried to shut down the Stock Exchange. There might have been one time they actually pulled it off back in the 1980s or 1990s. And in 2001, there were plans to put together a Wall Street action right after the IMF actions in Washington that fall. But then 9/11 happened, three blocks away from the proposed site of the action, and we had to drop our plans. My assumption was that doing anything anywhere near Ground Zero was going to be off-limits for decades—both practically and symbolically. And more than anything, I was unclear about what this call to occupy Wall Street hoped to accomplish.

No one was really sure. But what also caught Georgia’s eye was another ad she’d seen online for what was being called a “General Assembly,” an organizing meeting to plan the Wall Street occupation, whatever it would turn out to be.

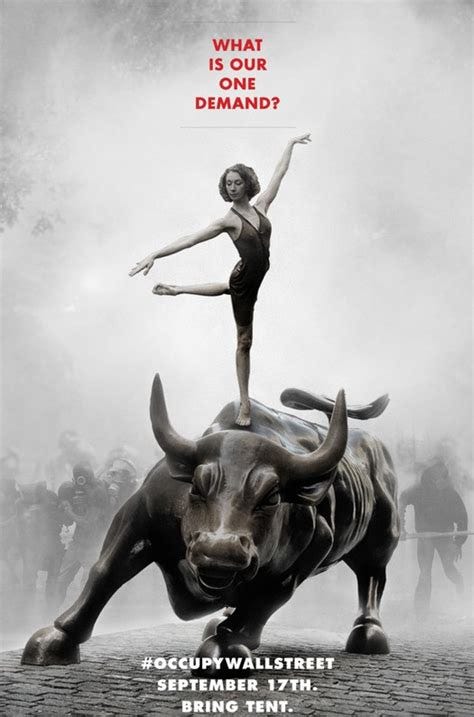

In Greece, she explained, that’s how they had begun: by occupying Syntagma Square, a public plaza near parliament, and creating a genuine popular assembly, a new agora, based on direct democracy principles. Adbusters, she said, was pushing for some kind of symbolic action. They wanted tens of thousands of people to descend on Wall Street, pitch tents, and refuse to leave until the government agreed to one key demand. If there was going to be an assembly, it was going to be beforehand, to determine what exactly that demand was: that Obama establish a committee to reinstate Glass-Steagall (the Depression-era law that had once prevented commercial banks from engaging in market speculation) or a constitutional amendment abolishing corporate personhood, or something else.

Colleen pointed out that Adbusters was basically founded by marketing people and their strategy made perfect sense from a marketing perspective: get a catchy slogan, make sure it expresses precisely what you want, then keep hammering away at it. But, she added, is that kind of legibility always a virtue for a social movement? Often, the power of a work of art is precisely the fact that you’re not quite sure what it’s trying to say. What’s wrong with keeping the other side guessing? Especially if keeping things open-ended lets you provide a forum for a discontent that everyone feels, but hasn’t found a way to express yet.

Georgia agreed. Why not make the assembly the message in itself, as an open forum for people to talk about problems and propose solutions outside the framework of the existing system? Or to talk about how to create a completely new system altogether. The assembly could be a model that would spread until there was an assembly in every neighborhood in New York, on every block, in every workplace.

This had been the ultimate dream during the Global Justice Movement, too. At the time we called it “contaminationism.” Insofar as we were a revolutionary movement, as opposed to a mere solidarity movement supporting revolutionary movements overseas, our entire vision was based on a kind of faith that democracy was contagious. Or at least, the kind of leaderless direct democracy we had spent so much care and effort on developing. The moment people were exposed to it, to watch a group of people actually listen to each other, and come to an intelligent decision, collectively, without having it in any sense imposed on them—let alone to watch a thousand people do it at one of the great Spokescouncils we held before major actions—it tended to change their perception of what was politically possible. Certainly, it had had that effect on me.

Our expectation was that democratic practices would spread, and, inevitably, adapt themselves to the needs of local organizations: it never occurred to us that, say, a Puerto Rican nationalist group in New York and a vegan bicycle collective in San Francisco were going to do direct democracy in anything like the same way. To a large degree, that’s what happened. We’d had enormous success transforming activist culture itself. After the Global Justice Movement, the old days of steering committees and the like were basically over. Pretty much everyone in the activist community had come around to the idea of prefigurative politics: the idea that the organizational form that an activist group takes should embody the kind of society we wish to create. The problem was breaking these ideas out of the activist ghetto and getting them in front of the wider public, people who weren’t already involved in some sort of grassroots political campaign. The media were no help at all: you could go through a year’s worth of media coverage and still not have the slightest idea that the movement was about promulgating direct democracy. So for contaminationism to work, we had to actually get people in the room. And that proved extraordinarily difficult.

Maybe, we concluded, this time it would be different. After all, this time it wasn’t the Third World being hit by financial crises and devastating austerity plans. This time the crisis had come home.

We all promised to meet at the General Assembly.

AUGUST 2

Bowling Green is a tiny park two blocks away from the Stock Exchange at the very southern end of Manhattan. It got its name because, in the seventeenth century, Dutch settlers used it for playing nine-pins. Now it’s a fenced green, with a fairly wide cobbled space to the north of it, and, directly to the north of that, a peninsular traffic island dominated by a large bronze statue of a bull stomping the earth. The bull, an image of barely contained and potentially deadly enthusiasm, had been adopted by the denizens of Wall Street as a symbol of the "animal spirits" (in John Maynard Keynes's coinage) driving the capitalist system. Ordinarily, it’s a quiet park, sprinkled with foreign tourists and street vendors selling six-inch replicas of the bull.

It was around 4:30 on the day of the General Assembly, and I was already slightly late for the 4:00 meeting—intentionally so. I had taken a circuitous route down Wall Street to get a sense of the police presence. It was worse than I’d imagined. There were cops everywhere: two different platoons of uniformed officers lounging around looking for something to do, two squads of horse cops standing sentinel on approach streets, scooter cops zipping up and down past the iron barricades built after 9/11 to foil suicide bombers. And this was just an ordinary Tuesday afternoon!

When I got to Bowling Green, what I found was, if anything, even more disheartening. At first, I wasn’t sure I had shown up for the right meeting at all. There was already a rally underway. Two TV cameras were pointed at an impromptu stage defined by giant banners, megaphones, and piles of preprinted signs. A tall man with flowing dreadlocks was making an impassioned speech about resisting budget cuts to a crowd of perhaps 80 people, arranged in a half-circle around him. Most of them seemed vaguely bored and uncomfortable, including, I noticed, the TV news crews. Upon closer inspection, the cameramen appeared to have left their cameras unattended. I found Georgia on the sidelines, her brow furrowed, as she looked out at the people assembled on stage.

“Wait a minute,” I asked. “Are those guys WWP?”

“Yeah, they’re WWP.”

I’d been out of town for a few years, so it took a moment to recognize them. For most anarchists, the Workers World Party (WWP) was the ultimate activist nemesis. Apparently led by a small cadre of mostly white party leaders who invariably lingered discreetly behind a collection of African American and Latino frontmen at public events, they were famous for pursuing a political strategy straight out of the 1930s: creating “popular front” coalitions like the International Action Center (IAC) or ANSWER (Act Now to Stop War and End Racism), composed of dozens of groups that turned out by the thousands to march with preprinted signs. Most of the rank-and-file members of these coalition groups were attracted by the militant rhetoric and an apparently endless supply of cash but remained blissfully unaware of what the central committee’s positions on world issues really were. These positions were almost a caricature of unreconstructed Marxism-Leninism—so much so that many of us had speculated from time to time that the whole thing was some kind of elaborate, FBI-funded joke. The WWP still supported, for instance, the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Chinese suppression of democracy protests at Tiananmen Square. They took such a strict “anti-imperialist” line that they actively supported anyone the U.S. government opposed—from the government of North Korea to Rwandan Hutu militias. Anarchists tended to refer to them as “the Stalinists.” Trying to work with them was out of the question; they had no interest in working with any coalition they did not completely control.

This was a disaster.

“How did the WWP end up in control of the meeting?” Georgia wasn’t sure. But we both knew that as long as they were in control, there was no possibility of a real assembly taking place. And indeed, when I asked a couple of bystanders what was going on, they confirmed the plan was for a rally, followed by a brief open mic, and then a march on Wall Street, where the leaders would present a long list of pre-established demands.

For activists dedicated to building directly democratic politics—horizontals, as we like to call ourselves—the usual reaction to this sort of thing is despair. It was certainly my first reaction. Walking into such a rally feels like walking into a trap. The agenda is already set, but it’s unclear who set it. In fact, it’s often difficult to find out what the agenda is until moments before the event begins when someone announces it on a megaphone. The very sight of the stage and stacks of preprinted signs, and hearing the word “march,” evoked memories of a thousand desultory afternoons spent marching along in platoons like some kind of impotent army, along a prearranged route, with protest marshals liaising with police to herd us into steel-barrier “protest pens.” Events in which there was no space for spontaneity, creativity, or improvisation—where everything seemed designed to make self-organization or real expression impossible. Even the chants and slogans were to be provided from above.

I spotted a cluster of what seemed to be the core WWP leadership group—you can tell because they tend to be middle-aged and white, and always hover just slightly offstage (those who appear on stage are invariably people of color).

One, a surprisingly large individual, broke off periodically to pass through the audience.

“Hey,” I said to him when he passed by, “you know, maybe you shouldn’t advertise a General Assembly if you’re not actually going to hold one.”

I may have put it in a less polite way. He looked down at me.

“Oh yeah, that’s solidarity, isn’t it? Insult the organizers. Look, I’ll tell you what. If you don’t like it, why don’t you leave?”

We stared at each other unpleasantly for a moment, and then he went away.

I considered leaving but noticed that no one else seemed particularly happy with what was happening either. To adopt activist parlance, this wasn’t really a crowd of verticals—that is, the sort of people who actually like marching around with pre-issued signs and listening to spokesmen from somebody’s central committee. Most seemed to be horizontals: people more sympathetic to anarchist principles of organization and nonhierarchical forms of direct democracy. I spotted at least one Wobbly—a young man with dark glasses and a black Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) T-shirt—several college students wearing Zapatista paraphernalia, and a few other obvious anarchist types. I also noticed several old friends, including Sabu, there with another Japanese activist, whom I’d known from street actions in Quebec City back in 2001.

Finally, Georgia and I looked at each other and both realized we were thinking the same thing: “Why are we so complacent? Why is it that every time we see something like this happening, we just mutter and go home?” Though I think the way we actually put it at the time was more like, “You know something? Fuck this shit. They advertised a General Assembly. Let’s hold one.”

So I walked up to a likely-looking stranger, a young Korean-American man irritatedly watching the stage—his name, I later learned, was Chris, and he was an anarchist who worked with Food Not Bombs. But I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that he looked pissed off.

“Say,” I asked, “I was wondering. If some of us decided to break off and start a real General Assembly, would you be interested?”

“Why, are there people talking about doing that?”

“Well, we are now.”

“Shit, yeah. Just tell me when.”

“To be honest,” volunteered the young man standing next to him—whose name, I later learned, was Matt Presto, and who, like Chris, would later become a key OWS organizer—“I was about ready to take off anyway. But that might be worth staying for.”

So, with the help of Chris and Matt, Georgia and I gathered some of the more obvious horizontals and formed a little circle of 20-odd people at the foot of the park, as far as we could get from the microphones. Almost immediately, delegates from the main rally appeared to call us back.

The delegates weren’t WWP folk—they tend to stay aloof from this sort of thing—but fresh-faced young students in button-down shirts.

“Great,” I muttered to Georgia. “It’s the ISO.”

The ISO is the International Socialist Organization. In the spectrum of activists, the WWP is probably on the opposite pole from anarchists, but ISO is annoyingly in the middle: as close as you can get to a horizontal group while still not actually being one. They’re Trotskyists, and in principle, in favor of direct action, direct democracy, and bottom-up structures of every kind—though their main role in any meeting seemed to be to discourage more radical elements from actually practicing these things. The frustrating thing about the ISO is that, as individuals, they tended to be such obviously good people. Most were likable kids, students mostly, incredibly well-meaning, and unlike the WWP, their higher-ups (and despite their theoretical support for direct democracy, the group itself had a very tightly organized, top-down command structure) did allow them to work in broad coalitions they didn’t control—if only with an eye to possibly taking them over. They were the obvious people to step in and try to mediate.

“I think this is all some kind of misunderstanding,” one of the young men told our breakaway circle. “This event isn’t organized by any one group. It’s a broad-based coalition of grassroots groups and individuals dedicated to fighting the Bloomberg austerity package. We’ve talked to the organizers. They say there’s definitely going to be a General Assembly after the speakers are finished.”

There were three of them, all young and clean-cut, and, I noticed, each of them, at one point or another, used exactly the same phrase: “a broad-based coalition of grassroots groups and individuals.”

There wasn’t much we could do. If the organizers were promising a General Assembly, we had to at least give them a chance. So we reluctantly complied and went back to the meeting.

Needless to say, no general assembly materialized. The organizers’ idea of an “assembly” seemed to be an open mic, where anyone in the audience had a few minutes to express their general political position or thoughts about some particular issue before we set off on the preordained march.

After about twenty minutes of this, Georgia took her turn to speak. I should note here that Georgia was, by profession, a performance artist. As such, she has always made a point of cultivating a certain finely fashioned public persona—basically, that of a madwoman. Such personas are always based on some elements of one’s real personality, and in Georgia’s case, there was much speculation among her close friends about just how much of it was put on. Certainly, she is one of the more impulsive people I’ve ever met. But she had a knack, at certain times and places, for hitting exactly the right note, usually by scrambling all assumptions about what was actually supposed to be going on.

Georgia started her three minutes by declaring, “This is not a General Assembly! This is a rally put on by a political party! It has absolutely nothing to do with the global General Assembly movement”—replete with references to Greek and Spanish assemblies and their systematic exclusion of representatives of organized political groups.

To be honest, I didn’t catch the whole thing because I was trying to locate other potential holdouts and convince them to join us once we again decided to defect. But like everyone who was there that day, I remember the climax, when Georgia’s time was up, and she ended up in a heated back-and-forth exchange with an African-American woman who’d been one of the WWP’s earlier speakers and who began an impromptu response.

“Well, I find the previous speaker’s intervention to be profoundly disrespectful. It’s little more than a conscious attempt to disrupt the meeting—”

“This isn’t a meeting! It’s a rally.”

“Ahem. I find the previous speaker’s intervention to be profoundly disrespectful. You can disagree with someone if you like, but at the very least, I would expect us all to treat each other with two things: respect and solidarity. What the last speaker did—”

“Wait a minute, you’re saying hijacking a meeting isn’t a violation of respect and solidarity?”

At this point, another WWP speaker broke in, with indignant mock astonishment, “I can’t believe you just interrupted a Black person!”

“Why shouldn’t I?” said Georgia. “I’m Black, too.”

I should point out here that Georgia is blond.

The reaction might be described as a universal “huh?”

“You’re what?”

“Just like I said. I’m Black. Do you think you’re the only Black person here?”

The resulting befuddlement bought her just enough time to announce that we were reassembling the real General Assembly and would meet back by the gate to the green in fifteen minutes. At that point, she was shooed off the stage.

There were insults and vituperations. After about a half-hour of drama, we formed the circle again on the other side of Bowling Green. This time, almost everyone still remaining abandoned the rally to come over to our side. We realized we had an almost entirely horizontal crowd: not only Wobblies and Zapatista solidarity folks, but also several Spaniards who had been active with the Indignados in Madrid, a couple of insurrectionist anarchists who’d been involved in the occupations at Berkeley a few years before, a smattering of bemused onlookers who had just come to see the rally (maybe four or five), and an equal number of WWP (not including anyone from the central committee) who reluctantly came over to monitor our activities. A young man named Willie Osterweil, who’d spent some time as a squatter in Barcelona, volunteered to facilitate.

We quickly determined we had no idea what we were actually going to do.

One problem was that Adbusters had already advertised a date for the action: September 17. This was a problem for two reasons. First, it was only six weeks away. It had taken over a year to organize the blockades and direct actions that shut down the WTO meetings in Seattle in November 1999. Adbusters seemed to think we could somehow assemble twenty thousand people to camp out with tents in the middle of Wall Street. But even assuming the police would let that happen—which they wouldn’t—anyone with experience in practical organizing knew that you couldn’t assemble numbers like that in a matter of weeks. Gathering a big crowd like that would usually involve drawing people from around the country, which would require support groups in different cities and, especially, buses, which would in turn require organizing all sorts of fund-raisers, since, as far as we knew, we had no money of any kind. (Or did we? Adbusters was rumored to have money. But none of us even knew if Adbusters was directly involved. They didn’t have any representatives at the meeting.)

Then there was the second problem: there was no way to shut down Wall Street on September 17 because September 17 was a Saturday. If we were going to do anything that would have a direct impact on—or even be noticed by—actual Wall Street executives, we’d have to figure out a way to still be around on Monday at 9 A.M. And we weren’t even sure the Stock Exchange was the ideal target. Just logistically, and perhaps symbolically, we’d probably have better luck with the Federal Reserve or the Standard & Poor’s offices, each just a few blocks away.

We decided to table that problem for the time being. We also decided to table the whole question of demands and instead form breakout groups. This is standard horizontal practice: everyone calls out ideas for working groups until we have a list (in this case, there were just four: Outreach, Communications/Internet, Action, and Process/Facilitation). Then the group breaks out into smaller circles to brainstorm, agreeing to reassemble an hour later, whereupon a spokesman for each breakout group presents report-backs on the discussion and any decisions collectively made.

I joined the Process group, which, predictably, was primarily composed of anarchists, determined to ensure the group became a model. We quickly decided that the group would operate by consensus, with an option to fall back on a two-thirds vote if there was a deadlock. There would always be at least two facilitators—one male, one female—one to keep the meeting running and the other to “take stack” (that is, the list of people who’ve asked to speak). We discussed hand signals and nonbinding straw polls, or “temperature checks.”

By the time we’d reassembled, it was already dark. Most of the working groups had only come to provisional decisions. The Action group had tossed around possible scenarios, but their main decision was to meet again later in the week to take a walking tour of the area. The Communications group had agreed to set up a listserv and meet to discuss a webpage. Their first order of business was to try to figure out what already existed (for instance, who had created the Twitter account called #OccupyWallStreet, since they didn’t seem to be at the meeting) and what, if anything, Adbusters had to do with it or what they had already done.

Outreach had decided to meet on Thursday to design flyers and to figure out how we should describe ourselves, especially in relation to the existing anti-cuts coalition. Several of the Outreach group—including my friend Justin, whom I knew from Quebec City—were working as labor organizers and were pretty sure they could get union people interested. All of us decided we’d hold another General Assembly, hopefully a much larger one, at the Irish Hunger Memorial nearby that Tuesday at 7:30 P.M.

Despite the provisional nature of all of our decisions—since none of us were quite sure if we were building on top of existing efforts or creating something new—the mood of the group was one of near-complete exhilaration. We felt we had just witnessed a genuine victory for the forces of democracy, one where exhausted modes of organizing had been definitively brushed aside. In New York, a victory like that was almost completely unprecedented. No one was sure exactly what would come of it, but at least for that moment, almost all of us were delighted at the prospect of finding out.

By the time we all headed home, it was already about eleven. The first thing I did was call Marisa.

“You can’t believe what just happened,” I told her. “You’ve got to get involved.”

THE 99 PERCENT

FROM: David Graeber david@anarchisms.org

SUBJECT: HELLO! Quick Question

DATE: August 3, 2011 12:46:29 AM CDT

TO: Micah White micah@adbusters.org

Hello Micah,

So, I just had the strangest day. About 80 people came down to assemble near the big bull sculpture at Bowling Green at 4:30 because we’d heard there was going to be a “General Assembly” to plan the September 17 action called by… well, you guys. We showed up and discovered that no, actually, no assembly; it was the Workers World Party with speakers, a microphone, and signs, doing a rally, then they were going to have a brief speak-out and a march. Normally, this is greeted with cynical resignation, but this time, a few of us… decided, “to hell with it,” assembled the horizontals, who turned out to be 85% of the crowd, defected, held a general meeting, created a structure and process, working groups, and got going on an actual organization. It was sort of a little miracle, and we all left feeling extremely happy for a change.

One question that came up, however, was: “What does Adbusters really have to do with any of this? Are they extending resources of any sort? Or was it just a call?” I said I’d check...

David

I sent that off before going to bed that night. The next morning, I got this reply:

Hey David,

Thank you for this report on what happened; I’m glad that you were there to pull things around. Here’s the situation…

At Adbusters, we’ve been kicking around the idea of a Wall Street occupation for a couple of months. On June 7, we sent out a listserv to our 90,000 email list of jammers with a short note floating the idea. The response was overwhelmingly positive, so we decided to run with it. The current issue of our magazine, the one that is just now coming onto newsstands (Adbusters #97—The Politics of Post-Anarchism), contains a double-page poster calling for the occupation on September 17. The front cover of the American edition also has an #OCCUPYWALLSTREET mini-picture. This will be like a slow fuse getting the word about the occupation out there to the English-speaking world for the next month or more…

At this point, we decided that given our limited resources and staff, our role at Adbusters could only be to get the meme out there and hope that local activists would empower themselves to make the event a reality. We’re following the same model of Spain, where the people—not political parties or organizations—decided on everything.

The “General Assembly” you attended was put together by an unaffiliated group—the same group that was behind the No Cuts NYC and Bloombergville (an anti-cuts protest camp that lasted about two weeks). My contact has been with “Doug Singsen” of No Cuts NYC. I don’t know anything about Doug or why the assembly was hijacked by the Workers World Party, or if that was intended from the start…

Micah

Adbusters had just thrown out an idea. They’d done this many times before, and in the past, nothing had ever really come of it. But this time, all sorts of different and apparently unrelated groups seemed to be trying to grab hold of it. However, we were the ones who ended up doing the organizing on the ground.

By the next day, the listserv for our little group was up, and all the people who had been at the original meeting started trying to figure out who we were, what we should call ourselves, and what we were actually trying to do. Once again, it all started with the question of the one single demand. After throwing out a few initial ideas—debt cancellation? Abolishing permit laws to legalize freedom of assembly? Abolish corporate personhood?—Matt Presto, who had been with Chris among the first to rally to us at Bowling Green, pretty much put the matter to rest when he pointed out that there were really two different sorts of demands. Some were actually achievable, like Adbusters’ suggestion—which had appeared in one of their initial publicity calls—of demanding a commission to consider restoring Glass-Steagall. Maybe a good idea, but was anyone really going to risk brutalization and arrest to get someone to appoint a committee? Appointing a committee is what politicians usually do when they don’t want to take any real action. Then there’s the kind of demand you make because you know that, even though overwhelming majorities of Americans think it’s a good idea, it’s unlikely to happen under the existing political order—say, abolishing corporate lobbying. But was it our job to come up with a vision for a new political order, or to help create a way for everyone to do so? Who were we, anyway, to come up with a vision for a new political order? So far, we were basically just a bunch of people who had come to a meeting. If we were all attracted to the idea of creating General Assemblies, it’s because we saw them as a forum for the overwhelming majority of Americans locked out of the political debate to develop their own ideas and visions.

That seemed to settle matters for most of us. But it led to another question: How exactly were we to describe that overwhelming majority of Americans who had been locked out of the political debate? Who were we calling to join us? The oppressed? The excluded? The people? All the old phrases seemed hackneyed and inappropriate. How to frame it in a way that made it self-evident why the obvious way to reclaim a voice was to occupy Wall Street?

That summer, I’d been giving almost constant interviews about debt, since I had just written a book on the subject, and had even been asked to weigh in now and then on venues like CNN, The Wall Street Journal, and even the New York Daily News (or, at least, on their blogs—I rarely got to be on the actual shows or in print editions). So I’d been trying to keep up with the U.S. economic debate. At least since May, when the economist Joseph Stiglitz had published a column in Vanity Fair called “Of the 1%, By the 1%, and For the 1%,” there had been a great deal of talk in newspaper columns and economic blogs about the fact that 1 or 2 percent of the population had come to grab an ever-increasing share of the national wealth, while everyone else’s income was either stagnating or, in real terms, actually shrinking.

What particularly struck me in Stiglitz’s argument was the connection between wealth and power: the 1 percent were the ones creating the rules for how the political system works, and had turned it into one based on legalized bribery:

Wealth begets power, which begets more wealth. During the savings-and-loan scandal of the 1980s—a scandal whose dimensions, by today’s standards, seem almost quaint—the banker Charles Keating was asked by a congressional committee whether the $1.5 million he had spread among a few key elected officials could actually buy influence. “I certainly hope so,” he replied. The personal and the political are today in perfect alignment. Virtually all U.S. senators, and most of the representatives in the House, are members of the top 1 percent when they arrive, are kept in office by money from the top 1 percent, and know that if they serve the top 1 percent well, they will be rewarded by the top 1 percent when they leave office.

The 1 percent held the overwhelming majority of securities and other financial instruments, and they also made the overwhelming majority of campaign contributions. In other words, they were exactly that proportion of the population that was able to turn their wealth into political power—and use that political power to accumulate even more wealth. It also struck me that since that 1 percent effectively was what we referred to as “Wall Street,” this was the perfect solution to our problem: Who were the excluded voices frozen out of the political system, and why were we summoning them to the financial district in Manhattan—and not, say, Washington, D.C.? If Wall Street represented the 1 percent, then we were everybody else.

FROM: David Graeber david@anarchisms.org

SUBJECT: Re: [september17discuss] Re: [september17] Re: A SINGLE DEMAND for the Occupation?

DATE: August 4, 2011 4:25:38 PM CDT

TO: september17@googlegroups.comWhat about the “99% movement”?

Both parties govern in the name of the 1% of Americans who have received pretty much all the proceeds of economic growth, who are the only people completely recovered from the 2008 recession, who control the political system, who control almost all financial wealth.

So if both parties represent the 1%, we represent the 99% whose lives are essentially left out of the equation.

David

The next day, Friday, August 5, was the day we’d set for the Outreach meeting, at the Writers Guild offices downtown, where my old friend Justin Molino worked. Everyone seemed to like the 99 percent idea. There were some tentative concerns: someone remarked that an “Other 98 percent” campaign had already been tried. Obviously, the idea wasn’t completely original. Probably any number of different people had thought of something along the same lines around the same time. But as it turned out, we happened to put it together at exactly the right time and place.

Before long, Georgia, along with Luis and Begonia, two of the Spanish Indignados, were preparing a flyer—our first—to advertise the Tuesday General Assembly, which we were already starting to call the “GA.”

MEETINGS

Marisa came to the next General Assembly (GA), and during the breakout, we got the idea of initiating a Trainings working group. Our group was composed mainly of young activists who had cut their teeth at Bloombergville. They were enthusiastic about the idea of consensus processes and direct action, but few had any real experience with either. Initially, the process was a shambles—many participants didn’t seem to understand that a block (i.e., a veto—normally to be used only as a last resort) was different from a “no” vote. Even the facilitators, who were supposed to be running the meetings, tended to start each discussion of proposals not by asking if anyone had clarifying questions or concerns but by simply saying, “Okay, that’s the proposal. Any blocks?”

Apart from training in democratic processes, there was a shortage of basic street skills. We needed to find people to provide legal training, if only so everyone would know what to do if they were arrested, as some of us were definitely going to be, whether or not we decided to do anything illegal. We needed medical training as well, to know what to do if someone nearby was injured. And we needed civil disobedience training to teach when and how to lock arms, go limp, and comply or not comply with orders.

I spent the next few weeks tracking down old friends from the Direct Action Network who had gone into hiding, retired, burnt out, given up, gotten jobs, or gone off to live on some organic farm. I had to convince them that this wasn’t just another false start, that it was real this time, and get them to join us and share their experience. It took a while, but gradually, many did filter back.

At that first GA at the Irish Hunger Memorial, we decided all subsequent GAs would be held in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village—rather than in the relatively desolate environs of Wall Street itself—because it was in the heart of a real New York community, the kind of place we hoped to see local assemblies eventually emerge. Marisa and I agreed to facilitate the first one, on August 13, since she had a good deal of experience with consensus processes. In fact, she was so good—and everyone else was so uncertain at first—that she ended up helping to facilitate the next four. She became the person holding everything together, at practically every working group meeting, coordinating and hatching plans. Without her, I’d be surprised if anything would have happened at all.

Over the next few weeks, a plan began to take shape. We decided that what we really wanted to achieve was something like what had already been accomplished in Athens, Barcelona, and Madrid, where thousands of ordinary citizens—most of them completely new to political mobilization—had been willing to occupy public squares in protest against the entire class of their respective countries. The idea would be to occupy a similar public space in New York to create a New York General Assembly, which could, like its European counterparts, act as a model of genuine direct democracy to counter the corrupt charade presented to us as “democracy” by the U.S. government. The Wall Street action would be a stepping-stone toward creating a whole network of such assemblies.

Those were our aims, but it was impossible to predict what would really happen on September 17. Adbusters had assured us there were 90,000 people following us on their website. They had also called for 20,000 people to fill the streets. That obviously wasn’t going to happen. But how many would really show up? And what would we do with the people once they did show up? We were all keenly aware of what we were up against. The NYPD numbered close to 40,000—Mayor Bloomberg liked to claim that if New York City had been an independent country, its police force would be the seventh-largest army in the world. Wall Street, in turn, was probably the single most heavily policed public space on the planet. Would it be possible to have any sort of action next to the Stock Exchange at all? Shutting it down, even for a moment, was pretty much out of the question—certainly not with only six weeks to prepare under the heightened security environment post-9/11.

Crazy ideas were tossed about at working group meetings and on the listserv. We were likely to be wildly outnumbered by the cops. Perhaps we could somehow use the overwhelming police presence against itself, to make them look ridiculous? One idea was to announce a cocaine blockade: we could form a human chain around the Stock Exchange and declare that we were allowing no cocaine to enter until Wall Street agreed to our demands (“And after three days, no hookers either!”). Another, more practical idea was for the working group that was already coordinating with people occupying squares in Greece, Spain, Germany, and the Middle East to create some sort of Internet hookup, and then project their images onto the wall of the Stock Exchange, allowing speakers from each occupation to express their opinions of Wall Street financiers directly. Something like that, we felt, would help with long-term movement building: it would actually accomplish something on the first day, rendering it a minor historical event—even if there never was a second day. Minor victories like that are always crucial; you always want to be able to go home saying you’ve done something no one else has ever done before. But, technically, given our constraints of time and money, it proved impossible to pull off.

To be perfectly honest, for many of us veterans, the greatest concern during those hectic weeks was how to ensure that the initial event wouldn’t turn out to be a total fiasco. We wanted to make sure that all the enthusiastic young people going into a major action for the first time wouldn’t end up beaten, arrested, and psychologically traumatized as the media, as usual, looked the other way.

Before the action launched, some internal conflicts had to be worked out. Most of New York’s grumpier hard-core anarchists refused to join in and, in fact, mocked us from the sidelines as “reformist.” More open “small-a” anarchists, such as myself, spent much of our time trying to make sure the remaining verticals didn’t institute anything that could become a formal leadership structure, which, based on past experience, would have guaranteed failure. The WWP pulled out of the organizing early on, but a handful of ISO students and their supporters—usually about a dozen in all—continually pushed for greater centralization.

One of the greatest battles was over the question of police liaisons and marshals. The verticals—taking their experience from Bloombergville—argued that it was a practical necessity to have two or three trained negotiators to interface with the police, and marshals to convey information to occupiers. The horizontals insisted that any such arrangement would instantly turn into a leadership structure that conveyed orders, since police will always try to identify leaders, and if they can’t find any, they create a leadership structure by making arrangements directly with the negotiators and then insisting that the negotiators (and marshals) enforce them. That issue actually went to a vote—or more precisely, a straw poll, where the facilitator asks people to put their fingers up (for approval), down (for disapproval), or sideways (for abstention or uncertainty) to get a sense of how everyone feels and determine whether it’s worth continuing. In this case, more than two-thirds strongly opposed creating either liaisons or marshals. At that moment, the commitment to horizontality was definitively confirmed.

There were controversies over the participation of various fringe groups, ranging from followers of Lyndon LaRouche to one woman from a shadowy (and possibly nonexistent) group called US Day of Rage, who systematically blocked any attempt to reach out to unions because she felt we should be able to attract dissident Tea Partiers. At one point, debates at the GA became so contentious that we ended up changing our hand signals: we had been using a signal for “direct response”—two hands waving up and down with fingers pointing—to be used when someone had crucial information (“No, the action isn’t on Tuesday, it’s on Wednesday!”) and was asking the facilitator to break through the stack of speakers to clarify. Before long, people were using the signal to mean, “The group needs to know just how much I disagree with that last statement,” and we were reduced to the spectacle of certain diehards sitting on the ground waving their index fingers at each other continuously as they went back and forth in an argument until everyone else forced them to stop. I ended up suggesting we get rid of “direct response” entirely and substitute one raised finger for a point of information. Once adopted, this change put an end to back-and-forths and improved the quality of our debate.

THE DAY

I’m not sure when or how the Tactical working group made their decision, but pretty early on, the emerging consensus was that we were going to occupy a park. It was really the only practical option.

Here, as in Egypt, we all knew that anything we said in a public meeting or wrote on a public listserv was certain to be known to the police. So when, a few weeks before the date, the Tactical group chose Chase Plaza—a spacious area in front of the Chase Manhattan Bank building, two blocks from the Stock Exchange, complete with a lovely Picasso sculpture and theoretically open to the public at all hours—and announced in our outreach literature that we’d hold our GA there on September 17, they assumed the city would just shut the place down. I spent most of the evening of the 16th at a civil disobedience training in Brooklyn, conducted by Lisa Fithian, another Global Justice veteran and seasoned organizer who now specialized in teaching labor groups more creative tactics. That night around midnight, a few of us—Marisa, Lisa, Mike McGuire (a scruffy, bearded anarchist veteran who had just arrived from Baltimore), and I—stopped off at Wall Street to reconnoiter, only to discover, sure enough, the plaza was fenced off and closed to the public for an unspecified period with no reason given.

“It’s all right,” said Marisa. “I’m pretty sure the Tactical group has a whole series of backup plans.” She didn’t know what those backup plans were—at that point, she had been working mainly with Trainings and the Video Live-Streaming group—but she was sure they existed. We poked around a bit, speculating about the viability of various open spaces, and eventually took the subway home.

The next day, the plan was for everyone to start assembling around noon by the bull statue at Bowling Green, but the four of us met an hour or two early, and I spent some time wandering around, snapping pictures on my iPhone of police setting up barricades around the Stock Exchange, and sending the images out on Twitter. This had an unexpected effect. The official #OccupyWallStreet Twitter account (which turned out to have been created and maintained by a small transgender collective from Montreal) immediately sent word that I was on the scene and seemed to have some idea what was going on. Within a couple of hours, my account had gained about 2,000 new followers. About an hour later, I noticed that every time I sent out an update, someone in Barcelona would translate it and send it out again in Spanish. I began to get a sense of just how much global interest there was in what was going on that day.

Still, the great mystery was how many people would actually show up. Since we hadn’t had time to make any serious efforts to organize transportation, it was really anyone’s guess. What’s more, we were well aware that if a large number of people did show up, we’d pretty much have no choice but to camp out somewhere, even if that hadn’t been the plan, since we hadn’t organized housing and didn’t have any place to put them.

At first, though, it didn’t seem like that was going to be much of a problem. Our numbers seemed disappointingly small. What’s more, many who showed up seemed decidedly offbeat—I remember a collection of about a dozen Protest Chaplains, dressed in white robes and singing radical hymns, and perhaps a dozen yards away, a rival chorus, also made up of about a dozen more singers, followers of Lyndon LaRouche, performing elaborate classical harmonies. Small knots of homeless traveling kids—or maybe they were just crusty-looking activists—would occasionally appear and take a few turns marching around the barricades the police had constructed around the bull statue, which was assiduously protected at all times by a squadron of uniformed officers.

Gradually, though, I noticed our numbers were starting to build. By the time Reverend Billy—a famous radical performance artist—began to preach from the steps of the Museum of the American Indian, at the south end of Bowling Green Park, it seemed like there were at least 1,000 of us. At some point, someone pressed a map into my hand. It had five different numbers on it, each corresponding to a park within walking distance that might serve as a suitable place for the GA. Around 2:30, word went out that we were all to proceed to location #5.

That was Zuccotti Park.

"Although it is fondly remembered by some, it is now largely seen as a failure."

Whatever the goal, the movement made it's mark on history and sent a message to the powers that shouldn't be.

For me, Occupy was more important than most people think it was. At the time (Sept 2011) I was 43 yrs old, from a small town in Fla. who never really lived anywhere where people from around the world were so prevalent in one city- Oakland, CA. That's where I was living at the time. I participated from day one....and learned more than I shared. I realized that I was not as educated or experienced in direct actions/movement building and wanted to soak it all up! There were so many workshops and areas at Oscar Grant Plaza (in front of Oakland City Hall) providing info and ways to help the effort in the plaza as well as the community and outward! Personally, I was active in the Anti-Repression Committee (doing bail support, court support, helping with actions, prisoner support work), took part in helping a woman w/ cancer in Alameda who was trying to save her house from a Wells Fargo foreclosure by committing to come and sit in the house certain days and hours each week, bringing food to share w/ residents and home defense support. The woman got her loan reorganized and saved her house! took part in the nightly General Assemblies, worked in the food tent and helped wash plates/silverware and donated food. Slept in the plaza in a tent and some nights took part in security of the plaza 2 hr. shifts. Took part in shutting down the port two times, going over to SF to support the occupy there at their city event "Occupy Wall Street West" (1/20/12). Took part in Occupy San Quentin and Occupy the Farm in Albany. There is more but you get the gist.

There was soo soo much going on in Oakland and the younger people who were well organized as anarchists/leftists knew how to do on-the-ground work and did so much for making opportunities for growth....to question and learn how to be autonomous. Was there a demand of the state? Hell no. Because tweeking a screwed up system is not a solution for real change. People who came to see and take part were getting a taste of what the people who work together can accomplish. I've taken what I've learned and continued unlearning and learning new ways of living outside the system and sharing what I learn w/ others.