In Defence of David Graeber and his Theory of Imaginary Counterpower

A response to Darren Allen's critique of The Dawn of Everything

David Graeber was a rationalist, democratic, technophilic socialist. He uncritically supported democracy, and was unable or unwilling to accept that it subordinates individuals, he was uncritical of leftist causes (such as feminism) and continually focused his ‘activism’ through statist party politics, he was uncritical of professionalism (firing shots at every job conceivable in his book Bullshit Jobs, yet curiously coy about attacking doctors, teachers, lawyers and so on), he was uncritical of technology — even lamenting that we’re not technologically advanced enough — and, tellingly, he was uncritical of state-imposed lockdowns (he died suddenly in September 2020 but uttered not a syllable of doubt about or during the tyranny of the prior six months). He couldn’t outline an anarchist society because he was not an anarchist.

- Darren Allen, in his review of The Dawn of Everything

Wow. A year after one of the world´s most respected anarchist thinkers dies mysteriously, Darren Allen had this to say about the book that he was working on for ten years, and which was meant to be his legacy.

Now, as a green anarchist, I also have my critique of David Graeber, who did indeed dream of a high-tech utopia in which science would allow him to live forever.

However, I maintain that Graeber’s work remains hugely important, and I think that those of us who interest ourselves in anarchist theory would do well to study it, even if we are unlikely to agree with him on everything.

If you don’t know who Darren Allen is, by the way, he is a leading green anarchist author from the U.K.

If you´re arriving late to the party, and you´re feeling adventurous, I invite you to take a stroll out through the garden, out past the realm of semi-respectable weirdos like me and into the intellectual avant-garde of Paul Cudenec, eventually you will reach the outer rim of post-Leftist anarchist thought, where you find the realm of Darren Allen.

I have written previously about Darren Allen’s work, notably here:

PRIMIVITISM VS. PRIMALISM - WHICH IS MORE BASED?

Ted Kaczynski, the notorious ‘domestic terrorist’ and radical author (who died last month) also went into the Woods. After he was arrested and his work became widely known, he became, for a short time, the darling of anarcho-primitivists such as John Zerzan, and with good reason, as

Now, let me state up front that I’m a fan of Darren Allen, and that I have been influenced by his work.

He’s a brilliant theorist, and he really doesn’t give a fuck about pissing people off, which is generally a quality that I appreciate in writers.

Sometimes, however, I find that he misses the mark. This is how he sums up The Dawn of Everything, the book that David Graeber co-wrote with the British archaeologist David Wengrow.

The Dawn of Everything. Quite the ambitious title. If you haven’t read the last and latest book by David Graeber, co-authored with David Wengrow (G&W), you might think that you’re going to learn something pretty remarkable. You’d be wrong though. You might get the feeling, after you start reading, that the narrative is leading somewhere new. Wrong again I’m afraid. As with Graeber’s other books, you’ll get anecdote after anecdote, fact after fact, theory after theory, hypothesis after hypothesis, all linked up into a deceptive narrative — Graeber is very good at making you feel you’re getting somewhere. But you’re not.

The point which G&W promise to deliver is an explanation of how we got in the terrible state we are in today (that, tellingly, is ‘everything’), how the world of misery, futility, coercion and control that covers the earth started, or ‘dawned’. This is framed by G&W as ‘how did we get stuck in one mode of social organisation?’ They find some evidence — not very much, but some — to suggest that in the period just before the horrors of civilisation, around ten thousand years ago, we ‘played’ at seasonal hierarchies, bowing down to a king in winter before gadding off into anarchic tribes during the holidays. Then, G&W say, we got disastrously ‘stuck’ in the monarchical mode.

But how? The reader has to wait right to the very end of the book to find the answer to the often teased question, ‘what went wrong?’. There, in the last itty-bitty section of the last chapter, we find out that this horrendous world came about because ‘people began defining themselves against each other’, because we became confused about the difference between ‘care and domination’ and between ‘external violence’ (i.e. warfare) and ‘internal care’ (our relation to our family and to our possessions).

That’s it.

Brutal. Imagine that´s your obituary. Good lord.

I actually read this review before I ever read The Dawn of Everything, and I’m glad it didn’t stop me from reading the book. In all honesty, I wonder whether Allen actually read the book thoroughly or whether he just flipped through it in order to bash it. He definitely seems to have a huge hate-on for David Graeber for some reason.

Although The Dawn of Everything is most definitely a mixed bag, I believe it is a very important work, and one well worth engaging with.

More important, however, is the broader legacy that David Graeber left.

Sure, the late scholar was wrong about some things, but he also brought a lot of great ideas to the table.

Now that he’s gone, it’s up to us to separate the wheat from the chaff.

I am pleased to report that the process is well underway. A book called As if already free, which reflects upon his legacy, was released in 2023, and will surely be the first of many works to do so.

Reflecting on David Graeber’s legacy, however, will be complicated by several factors.

First is his mysterious death. The introduction to As if already free straight up says that David Graeber died of COVID, which isn’t true. Are academics planning to pretend that his death wasn’t mysterious?

How did David Graeber die?

Hey Gang, For the better part of a year, I’ve been pretty obsessed with David Graeber, the anarchist activist best known for his central role in the Occupy Movement. I’ve read three of his books, tons of his articles, watched countless interviews, and listened to a lot of his lectures.

Second is the question of The Dawn of Everything, the book which was meant to be Graeber’s legacy, and which was released after his death.

In addition to being full of errors, fallacies, omissions, bad scholarship, and bad theory, The Dawn of Everything seems basically opposed to the idea that human societies are capable of organizing themselves on an egalitarian basis. How could an anarchist write such a book? Did David Graeber lose faith in humanity near the end of his life? Is The Dawn of Everything really the book that Graeber might to write? Are the book’s faults due to poor editorial decisions made after his death? Or did Graeber lose the plot along the way somewhere?

According to David Wengrow, the book’s co-author, The Dawn of Everything was completed three weeks prior to Graeber’s death. He writes:

David Rolfe Graeber died aged fifty-nine on 2 September 2020, just over three weeks after we finished writing this book, which had absorbed us for more than ten years. It began as a diversion from our more ‘serious’ academic duties: an experiment, a game almost, in which an anthropologist and an archaeologist tried to reconstruct the sort of grand dialogue about human history that was once quite common in our fields, but this time with modern evidence. There were no rules or deadlines.

We wrote as and when we felt like it, which increasingly became a daily occurrence. In the final years before its completion, as the project gained momentum, it was not uncommon for us to talk two or three times a day. We would often lose track of who came up with what idea or which new set of facts and examples; it all went into ‘the archive’, which quickly outgrew the scope of a single book… Realizing we didn’t want to end the intellectual journey we’d “many of the concepts introduced in this book would benefit from further development and exemplification, we planned to write sequels: no less than three.

But this first book had to finish somewhere, and at 9.18 p.m. on 6 August David Graeber announced, with characteristic Twitter-flair (and loosely citing Jim Morrison), that it was done: ‘My brain feels bruised with numb surprise.”

Wengrow also mentions that the book had at least three editors:

Of one thing I am certain: this book would not have happened – or at least not in anything remotely like its present form – without the inspiration and energy of Melissa Flashman, our wise counsel at all times in all things literary. In Eric Chinski of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Thomas Penn of Penguin UK we found a superb editorial team and true intellectual partners.

Does a book really need two authors and three editors? That sounds like committee writing to me.

At the end of the day, I suppose that it doesn’t matter all that much now. David Graeber is dead, and he left behind a great wealth of ideas, theories, critiques, manifestoes, and observations.

Some of his ideas will resonate with some people, some will resonate with others.

If nothing else, The Dawn of Everything has started a lively debate about the Story of Humanity, and I for one think that this is a very good thing.

THE DAWN OF EVERYTHING

In 2004, David Graeber wrote a short book called Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, in which he asked why anarchists don’t take more of an interest in anthropology, which after all is the only academic discipline which actually studies real-world stateless societies in detail.

In that book, Graeber pointed out that anarchists could learn a lot from anthropology, raising many interesting questions in the process.

Years later, Graeber teamed up with a British archaeologist named David Wengrow, and the pair dedicated themselves to a massive undertaking, which was to basically to conduct an analysis of both the anthropological record AND the archaeological record in order to come up with ideas that would help anarchists to reverse-engineer an anarchist society based on examples of real-world egalitarian societies.

In other words, The Dawn of Everything was clearly meant to pick up where Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology left off.

Really, I think that Graeber was attempting to come up with his version of an anarchist World-Story, although he seems not to have been fully consciously aware about what he was doing.

He’s not the first to attempt such a thing. Anarchists have been on the case for a minute now.

The Dawn of Everything follows Fredy Perlman´s Against His-Story, Against Leviathan, Peter Gelderloos´s Worshipping Power, and the work of James C. Scott.

It also follows John Zerzan, Ted Kaczynski, Murray Bookchin, Derrick Jensen, and Abdullah Ocalan. Because anarchists begin with a rejection of the logic of domination, it’s pretty important to have our own Mythos.

If your point of departure is that things don’t have to be the way they are, it’s essential to have a good explanation for how they came to be this way.

To my mind, this is as noble and as worthy as any academic could embark upon, and Graeber and Wengrow should be honoured for the valiant effort they made, although I must concur with Allen that their efforts were not altogether successful.

CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE DAWN OF EVERYTHING

This is a big topic. I am far from alone in having complicated feelings about this book. Many people who are into political anthropology are in an uproar about it.

The critical reception to The Dawn of Everything has been extremely mixed. It has earned both high praise and scathing condemnation.

If you want to see an anthropologist rave about what a great contribution that Graeber and Wengrow have made towards “unwhitewashing history”, I refer you to this video:

If you’d like to see a more critical take, I refer to the following video, which is one of a whole series of videos unpacking the book:

Man, is this book ever a head-scratcher…

In it, the authors call into question whether egalitarian societies even ever existed, which is the last thing I would ever would have imagined that an anarchist anthropologist would say.

There’s even a chapter called Why the State has no Origin, in which the authors pretend not to know what a state is in order to argue that human societies have never been stateless, and that new discoveries of Ice Age grave sites have overturned the standard narrative that human beings have egalitarian origins.

All this is completely ridiculous, as we shall see. It’s truly befuddling how full of errors, fallacies, and omissions The Dawn of Everything is. Previous to its publication, David Graeber had impeccable credentials as a scholar.

Because the book was published after his death, I wonder whether it actually is the book that he meant to write. Perhaps the original text was tortured to death by an editorial committee.

Anyway, I plan to begin my deep dive into The Dawn of Everything soon, but for now I will simply argue that David Graeber should be judged by his life’s work, not just this one book.

In response to Darren Allen’s argument that David Graeber was nothing more than a rationalist, materialist, Leftist technophile, I would prefer to go back to an earlier work, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology in which Greaber presents “the Theory of Imaginary Counterpower”.

Now, this really is a very brilliant idea. I am not exaggerating when I say that if people really took this idea to heart, it would revolutionize the entire discipline of political science.

It would also herald the end of the Age of Reason and the paradigm of secular materialism.

This idea has definitely completely changed the way that I think about politics, and I think that it offers us a glimpse into the world on the other side of the paradigm shift we are currently going through.

David Graeber was a huge believer that what was holding us back as a species was a lack of imagination about possibilities exist, and I am in total agreement with him on this point.

Without further ado, I present:

THE THEORY OF IMAGINARY COUNTERPOWER

In typical revolutionary discourse a “counterpower” is a collection of social institutions set in opposition to the state and capital: from selfgoverning communities to radical labor unions to popular militias…

When such institutions maintain themselves in the face of the state, this is usually referred to as a “dual power” situation. By this definition most of human history is actually characterized by dual power situations, since few historical states had the means to root such institutions out, even assuming that they would have wanted to. But Mauss and Clastres’ argument suggests something even more radical. It suggests that counterpower, at least in the most elementary sense, actually exists where the states and markets are not even present; that in such cases, rather than being embodied in popular institutions which pose themselves against the power of lords, or kings, or plutocrats, they are embodied in institutions which ensure such types of person never come about. What it is “counter” to, then, is a potential, a latent aspect, or dialectical possibility if you prefer, within the society itself.

This at least would help explain an otherwise peculiar fact; the way in which it is often particularly the egalitarian societies which are torn by terrible inner tensions, or at least, extreme forms of symbolic violence.

Of course, all societies are to some degree at war with themselves. There are always clashes between interests, factions, classes and the like; also, social systems are always based on the pursuit of different forms of value which pull people in different directions. In egalitarian societies, which tend to place an enormous emphasis on creating and maintaining communal consensus, this often appears to spark a kind of equally elaborate reaction formation, a spectral nightworld inhabited by monsters, witches or other creatures of horror. And it’s the most peaceful societies which are also the most haunted, in their imaginative constructions of the cosmos, by constant specters of perennial war. The invisible worlds surrounding them are literally battlegrounds. It’s as if the endless labor of achieving consensus masks a constant inner violence— or, it might perhaps be better to say, is in fact the process by which that inner violence is measured and contained—and it is precisely this, and the resulting tangle of moral contradiction, which is the prime font of social creativity. It’s not these conflicting principles and contradictory impulses themselves which are the ultimate political reality, then; it’s the regulatory process which mediates them.

Some examples might help here:

Case 1: The Piaroa, a highly egalitarian society living along tributaries of the Orinoco which ethnographer Joanna Overing herself describes as anarchists. They place enormous value on individual freedom and autonomy, and are quite selfconscious about the importance of ensuring that no one is ever at another person’s orders, or the need to ensure no one gains such control over economic resources that they can use it to constrain others’ freedom. Yet they also insist that Piaroa culture itself was the creation of an evil god, a two-headed cannibalistic buffoon. The Piaroa have developed a moral philosophy which defines the human condition as caught between a “world of the senses,” of wild, pre-social desires, and a “world of thought.” Growing up involves learning to control and channel in the former through thoughtful consideration for others, and the cultivation of a sense of humor; but this is made infinitely more difficult by the fact that all forms of technical knowledge, however necessary for life are, due to their origins, laced with elements of destructive madness. Similarly, while the Piaroa are famous for their peaceableness—murder is unheard of, the assumption being that anyone who killed another human being would be instantly consumed by pollution and die horribly—they inhabit a cosmos of endless invisible war, in which wizards are engaged in fending off the attacks of insane, predatory gods and all deaths are caused by spiritual murder and have to be avenged by the magical massacre of whole (distant, unknown) communities.

Case 2: The Tiv, another notoriously egalitarian society, make their homes along the Benue River in central Nigeria. Compared to the Piaroa, their domestic life is quite hierarchical: male elders tend to have many wives, and exchange with one another the rights to younger women’s fertility; younger men are thus reduced to spending most of their lives chilling their heels as unmarried dependents in their fathers’ compounds. In recent centuries the Tiv were never entirely insulated from the raids of slave traders; Tivland was also dotted with local markets; minor wars between clans were occasionally fought, though more often large disputes were mediated in large communal “moots.” Still, there were no political institutions larger than the compound; in fact, anything that even began to look like a political institution was considered intrinsically suspect, or more precisely, seen as surrounded by an aura of occult horror. This was, as ethnographer Paul Bohannan succinctly put it, because of what was seen to be the nature of power: “men attain power by consuming the substance of others.” Markets were protected, and market rules enforced by charms which embodied diseases and were said to be powered by human body parts and blood. Enterprising men who managed to patch together some sort of fame, wealth, or clientele were by definition witches. Their hearts were coated by a substance called tsav, which could only be augmented by the eating of human flesh. Most tried to avoid doing so, but a secret society of witches was said to exist which would slip bits of human flesh in their victims’ food, thus incurring a “flesh debt” and unnatural cravings that would eventually drive those affected to consume their entire families. This imaginary society of witches was seen as the invisible government of the country. Power was thus institutionalized evil, and every generation, a witch-finding movement would arise to expose the culprits, thus, effectively, destroying any emerging structures of authority.

Case 3: Highland Madagascar, where I lived between 1989 and 1991, was a rather different place. The area had been the center of a Malagasy state— the Merina kingdom—since the early nineteenth century, and afterwards endured many years of harsh colonial rule. There was a market economy and, in theory, a central government—during the time I was there, largely dominated by what was called the “Merina bourgeoisie.” In fact this government had effectively withdrawn from most of the countryside and rural communities were effectively governing themselves. In many ways these could also be considered anarchistic: most local decisions were made by consensus by informal bodies, leadership was looked on at best with suspicion, it was considered wrong for adults to be giving one another orders, especially on an ongoing basis; this was considered to make even institutions like wage labor inherently morally suspect. Or to be more precise, unmalagasy—this was how the French behaved, or wicked kings and slaveholders long ago. Society was overall remarkably peaceable. Yet once again it was surrounded by invisible warfare; just about everyone had access to dangerous medicine or spirits or was willing to let on they might; the night was haunted by witches who danced naked on tombs and rode men like horses; just about all sickness was due to envy, hatred, and magical attack. What’s more, witchcraft bore a strange, ambivalent relation to national identity. While people made rhetorical reference to Malagasy as equal and united “like hairs on a head,” ideals of economic equality were rarely, if ever, invoked; however, it was assumed that anyone who became too rich or powerful would be destroyed by witchcraft, and while witchcraft was the definition of evil, it was also seen as peculiarly Malagasy (charms were just charms but evil charms were called “Malagasy charms”). Insofar as rituals of moral solidarity did occur, and the ideal of equality was invoked, it was largely in the course of rituals held to suppress, expel, or destroy those witches who, perversely, were the twisted embodiment and practical enforcement of the egalitarian ethos of the society itself.

Note how in each case there’s a striking contrast between the cosmological content, which is nothing if not tumultuous, and social process, which is all about mediation, arriving at consensus. None of these societies are entirely egalitarian: there are always certain key forms of dominance, at least of men over women, elders over juniors. The nature and intensity of these forms vary enormously: in Piaroa communities the hierarchies were so modest that Overing doubts one can really speak of “male dominance” at all (despite the fact that communal leaders are invariably male); the Tiv appear to be quite another story. Still, structural inequalities invariably exist, and as a result I think it is fair to say that these anarchies are not only imperfect, they contain with them the seeds of their own destruction. It is hardly a coincidence that when larger, more systematically violent forms of domination do emerge, they draw on precisely these idioms of age and gender to justify themselves.

Still, I think it would be a mistake to see the invisible violence and terror as simply a working out of the “internal contradictions” created by those forms of inequality. One could, perhaps, make the case that most real, tangible violence is. At least, it is a somewhat notorious thing that, in societies where the only notable inequalities are based in gender, the only murders one is likely to observe are men killing each other over women. Similarly, it does seem to be the case, generally speaking, that the more pronounced the differences between male and female roles in a society, the more physically violent it tends to be. But this hardly means that if all inequalities vanished, then everything, even the imagination, would become placid and untroubled. To some degree, I suspect all this turbulence stems from the very nature of the human condition. There would appear to be no society which does not see human life as fundamentally a problem. However much they might differ on what they deem the problem to be, at the very least, the existence of work, sex, and reproduction are seen as fraught with all sorts of quandaries; human desires are always fickle; and then there’s the fact that we’re all going to die. So there’s a lot to be troubled by. None of these dilemmas are going to vanish if we eliminate structural inequalities (much though I think this would radically improve things in just about every other way). Indeed, the fantasy that it might, that the human condition, desire, mortality, can all be somehow resolved seems to be an especially dangerous one, an image of utopia which always seems to lurk somewhere behind the pretentions of Power and the state. Instead, as I’ve suggested, the spectral violence seems to emerge from the very tensions inherent in the project of maintaining an egalitarian society. Otherwise, one would at least imagine the Tiv imagination would be more tumultuous than the Piaroa.

Now, c´mon, Darren… You telling me the guy who came up with the Theory of Imaginary Counterpower was a rationalist? Sure, at his day job, fine. You kind of have to be if you´re an academic. But in his heart? C´mon. You think someone like Chomsky could come up with such an idea? I don’t think so.

That said, The Dawn of Everything did fail for a simple reason, namely that Graeber and Wengrow don’t go far enough.

THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS POLITICALLY CORRECT ANTHROPOLOGY

As much as it kills me, I have to give the last word to Allen .

In my opinion, Graeber and Wengrow did fail to do what they set out to do in The Dawn of Everything, and they failed because they tried to create a politically correct anthropology, which is a fool´s errand, if you take a second to think about it.

If I were to make a statement about whether homosexuality is morally acceptable, for instance, I would make it within a given cultural framework.

It may be politically correct for two men to marry in 2023, but it would be unthinkable in many traditional societies.

There is no such thing as something as politically correct anthropology because if I were to judge another culture by the moral standards of my own culture, I would be imposing one type of morality onto another people.

Even if we were to adopt natural law theory as a basis for some kind of universal morality, cultural differences would not vanish. Different groups of human beings will make different situations and come up with different answers to the questions posed by life. As the Zapatista slogan goes, we want a world where many worlds fit.

So am I a cultural relativist then? I guess so, although I might need to work out the finer points here, because I reject postmodernism and moral relativism.

Anyway, over the course of David Graeber’s career, he seems to have made a habit of skirting issues that would be unpopular with his fans.

For instance, Graeber appears to have been a 9/11 truther, but he didn’t broadcast his views on this topic. He was also quite quiet about LBGT issues, which kind of makes me wonder. Surely, anthropology must have a lot to say on that subject!

David Graeber never really went woke, but he seems to have been quite aware where his bread was buttered, and quite willing to hold his tongue on certain topics. Really, I think that Graeber was an affable, agreeable person who wanted to be liked, and who enjoyed his status as a rockstar academic. Although he did talk about some controversial topics, he definitely picked his battles.

He also definitely was open to ideas considered heretical in archaeology. For instance, one gets the distinct feeling that he believes, as Marcel Mauss did, that there was extensive trans-Pacific ocean travel long before Columbus, but he won’t just come out and say so. You have to read between the lines.

He was also aware of the freakier side of anthropological theory. Who else in academia took Peter Lamborn Wilson or the theory of the Bicameral Mind seriously?

THERE’S NO TALKING ABOUT POLITICS WITHOUT TALKING ABOUT SEX

David Graeber once said “Anthropologists study taboo”. Yet over the course of his career he seems to have chosen to steer clear of certain topics, including sex and drugs.

The question of sex is particularly important, because sex is central to politics. In order to survive, a culture must be geared towards successful reproduction.

In more ways that one, sex is THE FUNDAMENTAL PROBLEM that culture must solve.

Why, you ask? Because sex is a constant source of tension between members of a given community.

For one thing, the demand for particularly desirable sex partners will always exceed the supply, leading inevitably to competition, jealousy, resentment, and potential conflicts.

For another, sex presents a domain of tension between the wishes of individuals and the need of the community for a certain degree of stability.

This tension MUST be mediated through culture. If it is not, it risks leading to violence, blood feuding, war, and statecraft.

As Allen wrote in another essay:

Sex rules the world. It was man’s restless sexual mania, his desire to fill every womb in the world, to fuck and fuck and fuck, which initially organised society, and which formed it into the horrifically violent place we see around us. It was so some men could get the power to fuck more women.

Amen to that. Finally, someone with the balls to tell it like it is.

If you ask me, the fact that SEX RULES THE WORLD should be included in the opening lecture of every Poli-Sci 101 course.

Statecraft is a logical extension of war, and every war is fought over control of resources, and like it or not, the reproductive labour of women is one of the most primal resources.

It`s not pleasant to think of, but guess what? Ain`t nothing pleasant about war.

WHAT ABOUT DRUGS?

But there´s way more here to unpack than just the sexual angle. There’s also the question of drugs.

Culture encodes a certain type of consciousness, and drugs provide ways of changing consciousness. Therefore, drugs can serve as ways of changing culture.

It is undeniable that ritual consumption of hallucinogenic substances has been part of many different cultures, including some which have stood up admirably against the onslaught of colonization.

To be fair, drugs are not the only way of changing consciousness. There are also ceremonies which involve fasting, feats of endurance, dancing, etc. My point is that consciousness change is an important subject when considered culture.

Consciousness change is a HUGE area of anthropology which David Graeber mostly ignored, which I think is odd, given that he’s the guy who came up with the Theory of Imaginary Counterpower.

Personally, I feel that if our goal is to create a new culture, the quest should also be to change our own minds, which is to say to come to a new understanding of what reality is and how we are to relate to one another.

If we want to take the idea of ethnogenesis seriously, I think we would do well to study different techniques of consciousness change.

HOW DO SEX, DRUGS AND CONSCIOUSNESS CHANGE RELATE TO MYTHOS?

I am guessing that most of my readers will be somewhat mystified about exactly I think David Graeber’s Theory of Imaginary Counterpower could actually be applied in a prefigurative way. Perhaps it will seem to some that I am advocating for revolutionaries to deliberately become crazy as part of a political strategy.

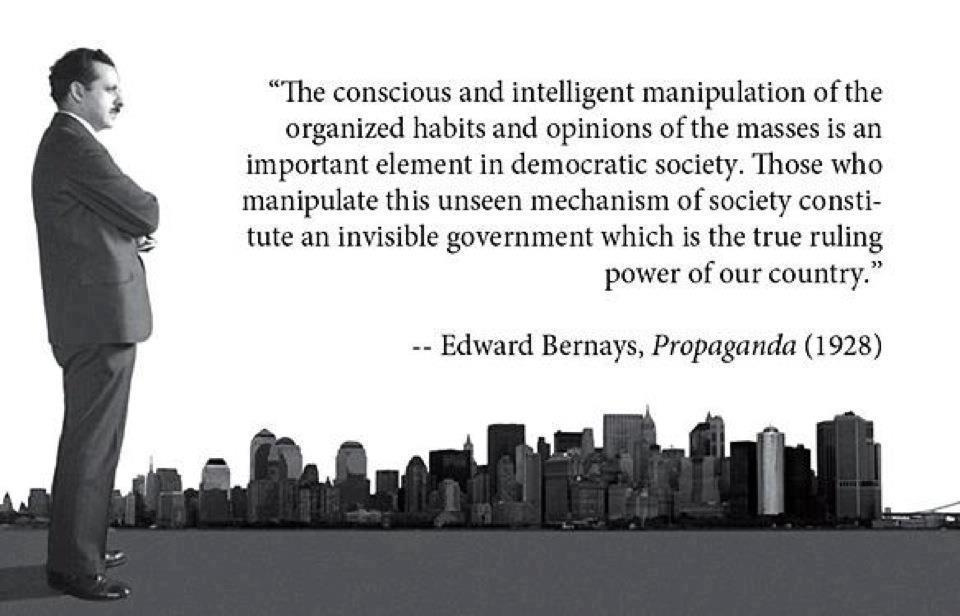

What I am arguing, rather, is that we are already crazy; that the World-Story of early 21st century industrial-consumer-capitalism is not the pinnacle of human achievement, but that Western Civilization is governed by a Mythos which is ultimately what we must overthrow.

The problem is the same for us as it was for the Tiv: an imaginary society of witches is seen as the invisible government of the country.

Metaphorically speaking, this is THE PROBLEM OF POLITICS.

The ancestral wisdom of primal societies often contains iterations of sophisticated political ideas that the West thinks it invented.

Or, as Plato put it:

What I have gotten from the work of David Graeber is this - the project of revolution is one of creating a new culture with a new Mythos.

In other words, the best thing that anarchists can do is to come up with our own World-Story, then build up a counterculture based on it.

Eventually, perhaps that counterculture could secede from the larger society and focus on becoming self-sufficient.

There’s where permaculture comes in, but we’ll get there. For now, what I want to do is to point out that we really do need to have a powerful Mythos if we hope to achieve truly great things.

THE STORY IS BROKEN.

Big News, everyone! I had a vision. Sort of. I think. NEVERMORE MEDIA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Maybe it will sound profound. Maybe it won’t. But I feel like I have a better idea of what exactly my mission in life is now.

WHAT ABOUT TECHNOLOGY?

Technology is yet another of Graeber’s blind spots, and this is one area where I will not offer any defence at all.

David Graeber was a technophile, pure and simple, and he seems to have disregarded critiques of civilization or technology which would have threatened his worldview.

In Allen’s words:

David Graeber doesn’t have a critical word to say about technology, he had no interest in engaging with our greatest critics of technology (such as Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich and Ted Kaczynski) and he yearned for force fields, teleportation, antigravity fields, tractor beams, jet packs and immortality drugs. The idea that technology beyond a limit automatically subordinates men and women to its needs, infects their consciousness with its utilitarian priorities, degrades man’s apprehension of the ineffable, trivialises nature, numbs awareness, forces dependency, supplants free choice and tends towards the colonisation of every sphere of human activity; none of this was of interest to David Graeber (as it is not to most socialists, including those who call themselves anarchists). It’s no surprise technology plays at best a walk-on part in ‘The Dawn of Everything’ — or its evils dismissed, once again, with a wave of the indeterministic hand.

Or, as Allen puts it:

Technology isn’t the biggest or most serious of G&W’s blindspots. Their gravest omission — and, actually, the source of Graeber’s enthusiasm for high-tech, socialist democracies — is also the subtlest and most disastrous. G&W tell us, again and again, that they want to show how early people self-consciously chose what kinds of societies they wanted to live in. They self-consciously chose monarchism, they self-consciously chose to build monuments, they self-consciously chose horticulture and they self-consciously chose to congregate in cities before self-consciously dispersing into smaller groups. G&W emphasise self-consciousness and choice because these are rational, quantitative attributes — precisely the attributes which lead to dominating, domesticating states. G&W want us to believe that early people were essentially technicians, rationally organising their societies. While telling us that we must ‘demythologise’ the past, G&W overlay it with their own materialist myth. Where, in ‘The Dawn of Everything’ is the sense of the transcendent, the immersion in the non-human and the love of the mysterious wild? These weren’t just secondary frills for primal people, they were the motivating core of their entire lives.

Bam. Deadly. No argument here. But there´s more:

Certainly, our distant ancestors were far more rational than we give them credit for, achieving almost miraculous feats of coordinated conceptualisation, but it was their irrational quality that distinguished them from the automatons which followed. G&W, rationalists in the enlightenment tradition, have no interest in this quality. None. This makes it impossible for them to understand how we fell from our original nature, what has happened to people as the power of their kings, professionals, tools, egos, states and systems have increased, what we can do about our confinement or how it is ever likely to end.

There is also no recognition of the relationship between people and place and how this is disrupted by technology. The wild has no place in ‘The Dawn of Everything’, nor do the lessons it can teach us and has taught us. The reader will search in vain for an understanding of the existential insecurity and attachment to idols (gods, politics, technology, money, groputhink, etc.) that separation from the wild engenders in man.

Innocence, sensitivity, presence, cheer, genius and love play no role in G&W’s ‘Dawn of Everything’ and the idea that people once exhibited these irrational qualities to any great extent, or that they are central to our understanding of what is wrong with the world, or how to overcome it; all this is ignored or brushed away as ‘Edenic myth-making’.

Ah, the irony. Really, what Graeber set out to do in The Dawn of Everything was to create an anarchist Mythos, yet they seemed to have spent years doing so without admitting to themselves what they were trying to do!

Think about it. What exactly is wrong with Edenic-myth making? What’s wrong with the idea that we once lived in a state of balance with nature? It seems to me like any anarchist Mythos would want to affirm that we once we were free, and that we could regain that freedom again.

G&W want us to believe that the socialist, democratic, feminist, leftist, professionally managed technocratic world they wish to inhabit is somehow right and natural, even eternal.

This is a shameful misrepresentation of humanity, one that has led, and can only lead, to misery.

Now, as much as it kills me to admit this, Allen hits the nail on the head here. The fact is that we live in an industrial capitalist society whose Mythos supports the existence of industrial capitalism as right, natural, and inevitable.

If you´re trying to adhere to the social mores of this society, and judge others by its moral standards, a meta-analysis of the anthropological record is an exercise in futility.

We´re studying this stuff in order to get away from our society, in order to look for new ways to encode new values that might be more conducive to freedom and social harmony.

For instance, anarchist societies govern themselves by taboo, as opposed to legal codes. If we want to do away with the law, we must develop ways of culturally encoding certain taboos and then passing them on. But how?

The truth is that every culture comes with its own obligations and taboos. There are no human societies where human beings are not expected to adhere to some kind of code of behaviour.

In an anarchist society, rather than a state telling you what you can and can’t do, your culture would tell you. In stateless societies, culture mediates and regulates social relations.

The question, then, is how to create such a culture.

Personally, I dream of a psychedelic society in which shamanic ceremonies promote group cohesion through boundary-dissolving experiences, but there are countless ways in which groups of people can create and reinforce a sense of belongingness through customs and culture.

Such customs, which often include singing, dancing, and drumming, are found throughout the entire world.

Graeber and Wengrow attempted to study anthropology objectively, rationally, without submersing themselves in the boundary-dissolving experiences that are necessary to understanding alternative visions of the world.

There’s only one problem - human beings are not rational creatures, and rationality has certain limits which intellectuals are often blind to.

CONCLUSION

Although I have many significant disagreements with him, I am tremendously grateful to David Graeber for the influence that he has had on my thought. Thanks to him, I now conceive of revolutionary political organizing differently.

The way I see it now, the goal for anarchist revolutionaries should be to create a permanent counterculture.

In other words, we must become a people.

THOSE WHO WALK AWAY FROM CAHOKIA (WHAT IS ETHNOGENESIS?)

Hey Gang! As you know, I’m a big believer that anarchist theory is in need of a big overhaul, and I’ve been doing my best to play my part. Lately, I’ve been wondering how many of my readers are actually familiar with post-left anarchist theory. I’m guessing that some of you probably think that post-left anarchism is a new thing, but it is absolutely not.

THE THREE QUESTIONS

This should begin with an effort to understand our current political reality, as well as what to do about it.

This should involve answering three questions, namely:

What are we?

Where do we come from?

Where are we going?

The answers to this question should then form the basis for an Anarchist Mythos complete with stories, songs, symbols, and customs encoding certain values.

This Mythos should then become the basis for a counterculture which consciously seeks to invert the values of consumer-capitalism, aiming towards increasing autonomy, interdependence, and self-sufficiency.

The eventual goal should be exodus, involving the founding of autonomous communities which are able to meet their needs independent of the state and fossil fuel economy.

The Dawn of Everything was a contribution towards an anarchist Mythos, but Graeber and Wengrow failed because they took a materialist, rationalist approach.

At the end of the day, there ain’t nothing rational about Mythos.

Would The Dawn of Everything have been a better book if David Graeber and David Wengrow had spent forty days in the desert with a bunch of peyote? I’m going with yes.

That said, I commend the two authors for their extremely valuable contributions to the project of creating an anarchist Mythos.

Ultimately, they raised more questions than they answered, and that’s okay. Now, the task passes to people like Darren Allen, who asks:

[W]hat would a functioning anarchist society look like? It would probably look something like the the early Neolithic societies that G&W focus on in ‘The Dawn of Everything’ (although G&W focus on them to justify industrial society). It would be comprised of small groups freely federated into a larger but powerless society, each self-sufficiently provisioning itself with a mixture of casual horticulture and hunting and gathering.

It would make use of some forms of simple technology — simple in the sense that it does not require specialist power to manage or hyper-specailised work to build — and it would be founded on an absolute refusal to ever take orders from anyone or anything — including (and here we completely depart from G&W’s modern world) from democratic majorities, priestly or professional experts, egoic compulsion, technical necessity and high-density urban life.

A functioning anarchist society would probably look loosely medieval, with a kind of prehistoric ‘base’ — in that the wild would be part of everyone’s lives — but with some carefully adopted techniques to help society run more smoothly; ‘carefully’ because technology would be widely considered to be something which can very easily obliterate the qualities that an anarchist society must be founded on.

These qualities — freedom, beauty, morality, love, truth, life and God — cannot be literally expressed. They can only come to us through myth, metaphor, ritual, love, pain and direct lived experience (particularly in the wild).

A functioning anarchist society would therefore be founded on truthful myth, ego-softening ritual, unconditional love, instructive pain (and an acceptance of death), meaningful natural activity and conscious being.

Such a society is not a ‘utopian dream’ to struggle towards, it is available to anyone, even here, in the midst of the Zone of Evil.

Indeed we will not see collective paradise in the world until you, dear reader, have manifested it in your life.

Amen to that. That seems like a good note to end on.

As for the question as to what the anthropological record can tell us about how to create an anarchist society, I remain convinced that this is a worthwhile and noble task for a great mind.

Yes, I will freely concede: the riddle remains unsolved, and the dragon remains unslain. But eventually some intrepid intellectual hero will take up the quest again.

Which brings me to my reason for writing this. Do you think Darren Allen is up to it?

That´s right, Darren. You think you can do a better job of coming up with an Anarchist Mythos than Graeber and Wengrow do in The Dawn of Everything?

If you do, I invite you to prove it.

Or is your strong suit finding fault in the ideas of others?