JARED DIAMOND IS A PROFESSIONAL DECEIVER

Why does the MSM promote the Bellicose School and ignore the Peace and Harmony Mafia?

Hey Folks!

As most of you are probably aware, one of my major interests is anthropology.

One of the age-old debates in anthropology is concerned with the question of human nature.

In The Dawn of Everything, David Wengrow and David Graeber trace this debate back to Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who traditionally represent the poles of this debate in university Poli Sci 101 classes.

Hobbes is often seen as the founder of the political Right, and Rousseau is often seen as the founder of the Left, though in reality the latter case is much more complicated.

Voltaire was much more historically important than Rousseau, but universities don’t want you thinking about Voltaire, so they focus on Rousseau, who offers a knock-off version of Voltaire’s true philosophy. It’s a sneaky way of avoiding talking about Voltaire, by far the most important revolutionary philosopher of the past half-millennium.

The contributions of these three thinkers are not what I plan to explore today, however. My current interest has to do with more recent manifestations of this debate.

In recent months, I have become increasingly convinced that there is an ideological war being waged between two schools - the Bellicose School and the Peace and Harmony Mafia, and that the former is promoted by people who have a specific political agenda, such as Jeffrey Epstein, who appears to have been such a close friend to Steven Pinker that the famous linguist volunteered his expertise to help the 21st century’s most prolific child molester clear up a little misunderstanding which apparently requires the professional opinion of an expert linguist.

Apparently, Steven Pinker helped Epstein’s lawyer Alan Dershowitz understand how “a reasonable person” would interpret laws against child prostitution.

Huh. Apparently Dershowitz needed help with that. And he seemed so reasonable when RFK was debating him about vaccines. Weird.

So apparently Pinker is more reasonable than Dershowitz in the pecking order of statist psychopaths. Good to know.

Anyway, we can assume that people like Jeffrey Epstein and Alan Dershowitz see Steven Pinker as an expert in imagining how “a reasonable person” would interpret laws. It’s notable that this suggests that Pinker’s expertise is in psychology and linguistics, not prehistory. This is a point that many anthropologists has made - that Pinker is unqualified to make the claims he makes.

The term “Bellicose School” was coined by the anthropologist Richard Lee, who did fieldwork with the Kalahari Bushmen, a famously egalitarian tribe of hunters and gatherers who live in the Kalahari desert in Southern Africa. Dr. Lee is a living legend in the world of anthropology, and is about an preeminent an authority on human behaviour as is alive today.

He coined the term “Bellicose School” in response to the derisive, slanderous attacks that hunter-gatherer specialists are constantly facing from Hobbesians, who see the entire field of sociobiology/behavioural ecology as the risible wishful thinking of a lame bunch of silly utopian hippies.

This has a lot to do with the fact that peaceful egalitarian hunters and gatherers got a lot of attention back in the 1960s, when the type of anarchistic ideology expressed by John Lennon in Imagine was commonplace (at least amongst the younger generation).

Don’t get me wrong, there’s a reason that stereotypes about silly, naive hippies exist. There are indeed such people, and they can get annoying.

But the Hobbesians are worse. They’re so committed to their bleak view of humanity that they actually mock people who present evidence for human cooperation or altruism. What a bunch of sad, pathetic losers.

The Bellicose School doesn’t want you focusing on peaceful egalitarian hunters and gatherers, and would rather that you focus on male chimpanzees, who do tend to be very aggressive and violent (although even here, there are real debates to be had about whether human researchers have altered chimpanzee behaviour by controlling the environments in which chimps are studied.

Furthermore, the Bellicose School has no problem playing fast and loose with the facts. The article that you are about to read was written by the British indigenous rights activist Stephen Corry, who was the Director-General of an NGO called Survival International from 1984 to 2021.

The article is entitled: Savaging Primitives: Why Jared Diamond’s “The World Until Yesterday” is Completely Wrong.

In it, Corry basically proves that Jared Diamond is a full-on intellectual con artist by showing that the statistics that he uses in his 2013 book The World Until Yesterday are so deceptive that the most reasonable conclusion is that the author included them in order to deceive his readers.

Given that Diamond’s fellow Bellicose School ideologue Steven Pinker has made a career out of lying with statistics, a pattern has now become detectable.

STEPHEN PINKER IS A LYING CHARLATAN SHYSTER

Hey Folks, Back in November, I travelled to Chiapas to attend a Sun Dance ceremony. During the ceremony, I had a vision in which my life’s work was revealed to me. Generally, journalists become specialists in some specific area; this specialization is called a beat.

What is the Bellicose School?

The Bellicose School is a group of anthropologists, primatologists, and other researchers who basically share the Hobbesian view of human nature.

Because human beings have strong instincts towards aggression, members of the Bellicose School believe that we need strong institutions in order to control people through punishment and the threat of punishment, because weaponized fear is the only way to keep violent human impulses in check. Basically, they’re true statists.

Richard Lee explains:

In The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker attempts to trace the contours of violence all the way from our primate ancestors through prehistory and history up to the present day. He argues that, despite the history of modern slaughters and advanced weaponry, the world is actually getting more peaceful. To make this case even remotely plausible, however, he has to posit inordinately high rates of violence for the earliest time periods.

In supporting the latter thesis, and drawn more or less directly from Hobbes’s [1969 (1651)] classic Leviathan, Pinker draws heavily on several modern sources from within anthropology: American archaeologists Lawrence Keeley (1996) and Steven LeBlanc (LeBlanc & Register 2003), and especially Richard Wrangham.

In Demonic Males, Wrangham & Peterson (1996) draw a direct line between evidence for chimpanzee males killing male conspecifics, through the purported violence in Homo erectus and archaic Homo sapiens and on to the undisputed evidence for warfare in historical human societies. As Wrangham & Peterson (1996) starkly put it, “[M]odern humans [are] the dazed survivors of a continuous 5-million-year habit of lethal aggression” (p. 63).

Keeley and LeBlanc offer the evidence for extensive warfare in tribal and chiefly societies in prehistory and inordinately high fatality rates. LeBlanc, in particular, attempts to universalize their findings with statements such as “we need to recognize and accept the idea of a non peaceful past for the entire time of human existence” and “from overwhelming evidence warfare has indeed shaped human history” (Le Blanc & Register 2003, p. 8).

These views provide the ammunition for Pinker’s thesis for an unbroken line of aggression from primatological, through hominid, to premodern human societies. Pinker adopts from van der Dennen (2005) the phrase “Peace and Harmony Mafia” to label critics who challenge the primordial violence thesis (see also Bowles 2009). Is the primordial violence thesis accurate? Long-term trending toward declining violence is, in some respects, a plausible thesis. We recognize that in earlier centuries Genghis Khan and Attila the Hun killed many thousands, not to mention the slaughterhouses of the Columbus, Cortex, and Pizarro expeditions to the New World, but is it fair to characterize all of human history this way?

As comforting and reassuring as it is, Pinker’s thesis of a steady decline in violence from prehistory to the present suffers from a serious flaw. By arguing for high death rates from warfare throughout history and prehistory, in band and tribal societies, as well as continuing into the era of states and empires, Pinker ignores or bypasses a large body of anthropological literature on the wide variability in war making throughout history; most important, he misses the crucial significance of the Neolithic Revolution.

It’s worth pointing out that some members of the Bellicose School, such as Jared Diamond and Richard Wrangham, are worth listening to. I’m not calling them all pseudo-scientific charlatans or anything like that.

I found Dr. Wrangham’s book Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human absolutely excellent. But he also wrote a book called Demonic Males.

You’re not exactly helping set us up for success, Dick…

Maybe you’re demonic, but I’m not.

(I probably will read this book at some point, though I suspect I will want to refute its main claims. After reading Catching Fire, though, I do have a lot of respect for Richard Wrangham. I don’t mean to paint him with the same brush as Steven Pinker, who is a straight-up pseudo-scientist. Wrangham might have a bleak view of human nature, but he is definitely a real scientist.)

What is the Peace and Harmony Mafia?

The term “Peace and Harmony Mafia” dates back to 2005, when a University of Groningen anthropologist named Johan van der Dennen published an open letter complaining of feeling shouted down by his colleagues. The moniker clearly implies that his colleagues were allowing their beliefs to twist evidence to suit their prejudices, in a classic example of the Grand Poobah of cognitive biases - the confirmation bias.

One unsurmountable truth lies at the crux of the debate - it is impossible for humans to be neutral about human nature. Although science seeks to be interpret data in as objective and dispassionately as possible, it would inhuman to be disinterested when the question being investigated is human nature.

Therefore, we have a situation where there are two groups of researchers who are equally convinced that they are correct about human nature and that their ideological opponents have succumbed to their own cognitive biases. It would be entertaining if it wasn’t for the fact that the Bellicose School is heavily promoted by the mainstream media whereas the Peace and Harmony Mafia are largely ignored.

Clearly, the Powers That Shouldn’t Be have an obvious preference for more pessimistic perspectives about human nature. The reasons why this would be are not hard to divine. If people think that human beings are quite capable of living in peace and harmony, they might get optimistic about the prospect of revolution, because optimism and revolutionary ideology tend to go together like bounce music and twerking.

Furthermore, not only do people all have their own belief systems, but those belief systems are influenced by religion, ideology, culture, upbringing, and even language.

In addition to the deep structure of belief, people always have personality differences that account for different attitudes. Some people are more optimistic and some are more pessimistic. This seems to be more a matter of disposition more than anything rational. So I can understand that it might be difficult for human beings to admit that we were nasty, brutal creatures if it were true. But there is every reason to believe that modern humans are more violent than our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

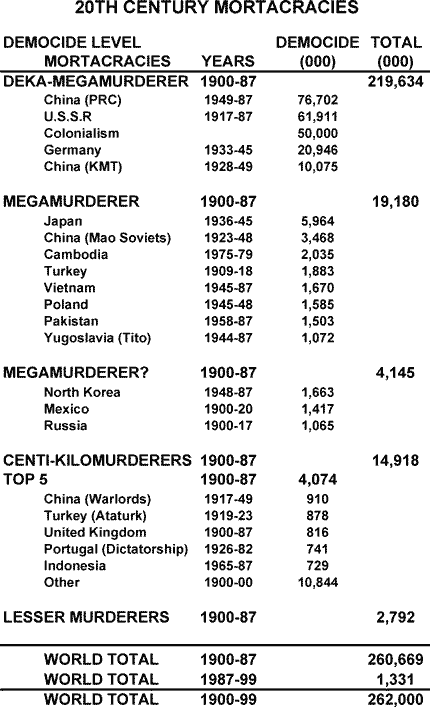

Look at these statistics for 20th century democides, for instance.

Are you really going to tell me that modern humans are less violent than our nomadic foraging ancestors? I’ll hear you out, but I’m not buying it.

(Please note that this list is biased. For example, it does not list the millions of casualties of the Vietnam War or C.I.A.-backed dirty wars in Latin America. A fully accurate list would actually be worse.)

Before I cover the Bellicose School, I’m going to include a lengthy excerpt from an article that was published by Scientific American back in 2017, because I feel it gives a good background to the debate.

In that article, entitled Nasty, Brutish and Short: Are Humans DNA-Wired to Kill?, journalist Josh Gabbatiss wrote of the Bellicose School:

At the heart of the popularization of this idea stands Napoleon Chagnon, sometimes called America’s “most controversial anthropologist.” Chagnon caused an uproar in 1968 when he published observations of the Yanomami people of Venezuela and Brazil, describing them as a “fierce people” who were in “a state of chronic warfare.” He asserted that Yanomami men who kill have more wives and therefore father more children: evidence of selection for violence in action. This represented a wild divergence from the anthropological consensus. Anthropologists criticized virtually every aspect of Chagnon’s work, from his methods to his conclusions. But for sociobiologists, this was a prime example that supported their theories.

Around the same time, David Adams, a neurophysiologist and psychologist at Wesleyan University, was inspired to investigate the brain mechanisms underlying aggression. He spent decades studying how different parts of the brain reacted when engaged in aggression. By using electrical stimulation of specific brain regions and through creating various lesions in mammalian brains, he sought to understand the origins of different antagonistic behaviors. But Adams found the public response to his work over the top: “The mass media would take [our work] and interpret it like we’d found the basis for war,” he says.

Tired of the way his results were being interpreted by both the media and the public, Adams eventually switched gears entirely.

In 1986, Adams gathered a group of 20 scientists, including biologists, psychologists, and neuroscientists, to issue what became known as the Seville Statement on Violence. It declared, among other things, that “it is scientifically incorrect to say that war or any other violent behavior is genetically programmed into our human nature.”

The statement, later adopted by UNESCO, an agency of the United Nations that promotes international collaboration and peace, was an effort to shake off the “biological pessimism” that had taken hold and make it clear that peace is a realistic goal.

The press, however, was not so enthralled by Adams’ new tack. “This is not interesting for us,” one major news network responded when he asked if they would cover the Seville statement, he recalls. “But when you do find the gene for war, call us back.”

The Seville statement by no means ended the academic debate. Since its release, various prominent researchers have continued to advance biological arguments for our innate tendency towards violence, in contradiction of both the statement and the views of many cultural anthropologists.

In 1996, Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist and primatologist at Harvard University, published his popular book Demonic Males, co-authored with science writer Dale Peterson, that argued we are “the dazed survivors of a continuous 5-million-year habit of lethal aggression.”

Central to this proposition is the idea that men, or “demonic males,” have been selected for violence because it confers advantages on them. Wrangham argued that murderous attacks by groups of male chimpanzees on smaller groups increased their dominance over neighboring communities, improving their access to food and female mates. Perhaps, like chimpanzees, ancestral men fought to establish dominance by killing rivals from other groups, thus securing greater reproductive success.

In Wrangham’s view, such behavior selected for males who are endowed with a certain desire for violence when the conditions are right: “the experience of a victory thrill, an enjoyment of the chase, a tendency for easy dehumanization (or ‘dechimpization’).”

“I think the growing evidence about innate propensities for violence have shown [the Seville statement] rather clearly to be simplistic and exaggerated at best,” says Wrangham.

A key proponent of this biological view is psychologist Steven Pinker, another Harvard researcher whose writing, particularly his 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, has significantly shaped the conversation about human violence in recent years. In his 2002 book The Blank Slate, Pinker wrote, “When we look at human bodies and brains, we find more direct signs of design for aggression,” explaining that men in particular bear the marks of “an evolutionary history of violent male-male competition.” One widely quoted estimate by Pinker places the death rate resulting from lethal violence in nonstate societies, based on archaeological evidence, at a shocking 15 percent of the population.

The article notes that the discussion includes anatomy:

Physical indicators, such as those studied by Carrier, can be viewed as evidence that selection for violence-enabling features has taken place. Carrier sees “signs of design for aggression” everywhere on the human body: In a recent paper, co-authored with biologist Christopher Cunningham from Swansea University, he suggests that our foot posture is an adaptation for fighting performance. He has even proposed, as part of his fist-fighting hypothesis, that the more robust facial features of men (as opposed to women) evolved to withstand a punch.

“I really don’t think it’s debatable that aggression has shaped human evolution,” agrees Aaron Sell, an evolutionary psychologist at Griffith University in Australia, who has explored the “combat design” of human males. Sell has compiled a list of 26 gender differences, ranging from “greater upper body strength” to “larger sweat capacity,” that suggest adaptation for fighting in human males. “It is a very incomplete list though,” he adds.

Many anthropologists remain unconvinced by those who suggest that there is an evolutionary advantage in violence and a deep biological explanation for conflict. “They’re just barking up the wrong tree,” says Douglas Fry, an anthropologist who specializes in the study of war and peace at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “We are well designed to prevent ourselves getting into lethal conflicts and to avoid the actual physical confrontation,” he argues, describing the idea that we are innately predisposed to violence as a cultural belief that is “just plain wrong.”

Douglas Fry, by the way, is the author of Beyond War, which argues against the false assumptions of Hobbesians.

Note that the foreword was written by Robert Sapolsky, who is a leading expert in primate behaviour.

I say this in order to make the point that the schism between the Bellicose School and the Peace and Harmony Mafia is not a battle between primatologists and anthropologists.

Many primatologists, including Sarah Hrdy, author of the highly influential book Mothers and Others, agree with the arguments that the hunter-gatherer specialists make.

The article continues:

[I]f violence and warfare are not ubiquitous throughout traditional societies, this would suggest that these human behaviors are not innate, but rather arise from culture. Fry has extensively examined both archaeological and contemporary evidence, and has documented over 70 societies that don’t make war at all, from the Martu of Australia, who have no words for “feud” or “warfare,” to the Semai of Malaysia, who simply flee into the forest when faced with conflict. He also argues that there is very little archaeological evidence for group conflicts in our distant past, suggesting war only became common as larger, sedentary civilizations emerged around 12,000 years ago—the opposite of Pinker’s conclusions.

As for our primate cousins, according to primatologist Frans de Waal of Emory University, their behavior has been cherry-picked to suit a more violent narrative for humanity. While chimp behavior may well shed light on human male tendencies for violence, de Waal points out that the other two of our three closest relatives, bonobos and gorillas, are less violent than us. In even the most peaceful human societies, of course, violence in one form or another is not totally unknown, and the same is true of these “peaceful” apes. Nevertheless, it is plausible that instead of descending from chimp-like ancestors, we come from a lineage of relatively peaceful, female-dominated apes, like bonobos. Chimpanzees might just be ultra-violent outliers.

“That our evolutionary success is based largely on our ability to be violent—that’s just wrong,” says biological anthropologist Agustín Fuentes, who is chair of anthropology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “The sum total of data we have from the genetics to the behavioral to the fossil to the archaeological suggests that is not the case.”

Scholars and researchers on both sides of the debate want their work applied to achieve more peaceful societies, and most agree that humans are capable of both great acts of violence and great acts of kindness. Yet from Chagnon onward, there has been a palpable degree of tension between those who hold opposing viewpoints.

In an open letter to de Waal in 2005, University of Groningen anthropologist Johan van der Dennen complained of feeling shouted down by the “peace and harmony mafia.”

At issue is the fact that for some a biological explanation suggests that violence is unavoidable. If we accept that violence is inherent, says Fuentes, we start to accept unpleasant behavior as inevitable and indeed natural in ourselves and those around us. “The old adage that ‘violence begets violence’ is true,” says AAA President Waterston. “A society that adopts and is adapted to violence tends to reproduce it, locating and leveraging the resources to do so.”

John Horgan, science journalist and author of The End of War, has been conducting informal surveys with students for years, and he reports that over 90 percent of respondents think we will never stop fighting wars. And when Adams and others conducted their own studies on student attitudes, they observed a worrying effect: There was a negative correlation between the belief that violence was innate and peace activism.

Even among those students who were actively campaigning for peace, 29 percent reported that they had previously been put off by “a pessimistic view that humans are intrinsically violent.”

Adams predicts that the level of apathy would be higher among those who abstained from activism altogether: “If you think that war is inevitable, why oppose it?” he says.

Such fatalistic attitudes are particularly worrying when held by those in power: They can be used “to justify military budgets, and not seek alternative solutions,” argues de Waal. Even Nobel Peace Prize–winning former U.S. President Barack Obama seems to believe that violence is bred into humanity: “War, in one form or another, appeared with the first man,” he said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. With Obama’s entire tenure spent leading a nation at war—albeit war that he inherited from his predecessor—Horgan has wondered if the former president’s personal belief in the “deep-roots theory of war” might have prevented him from more actively seeking peace.

But Obama, like Hobbes and Pinker, has also argued that society is equipped to fight the supposed biological imperative for violence: We have increasingly created codes of law and philosophies to limit violent acts, thanks to our capacity for empathy and reason. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker elegantly charts what he sees as a decline in violence, from the frightening 15 percent of violent deaths in nonstate societies down to 3 percent of deaths attributed to war, genocide, and other human-made disasters in the 20th century—a period that includes two world wars.

Waterston, exasperated by “the tired assumption that violence is rooted in ‘human nature,’” explains that for her the question should simply be about what circumstances are required for there to be less violence. Yet those seeking biological explanations see themselves as getting to the core of the issue in order to answer this question. Carrier offers an analogy to alcoholism: If you have a predisposition to drinking excessively, you must recognize those tendencies, and the reasons behind them, in order to fight them. “We want to prevent violence in the future,” says Carrier, “but we’re not going to get there if we keep making the same mistakes over and over again because we are in denial about who we are.” Chimpanzee research, for example, demonstrates how balanced power between groups tends to limit violence. “The same is clearly true of humans,” Wrangham notes. “Probing that simple formula, with all its complexities, seems to me a very worthwhile endeavor.”

There may be disagreement about how to get there, but all involved are trying to attain the same end goal. “An evolutionary analysis does not purport to condemn humans to violence,” explains Wrangham. “What it does achieve is a more precise understanding of the conditions that favor the highly unusual circumstance of peace.”

I suspect that the many indigenous nations who didn’t traditionally practice warfare would be surprised to learn that peace is highly unusual, because some tribes have been living in peace for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years. As noted above, some indigenous languages did not even have a word for war before coming into contact with Europeans.

That said, maybe that’s just a quirk of linguistics or something. It’s probably just a fluke that some humans don’t know about this aspect of human nature.

After all, anything who has read Steven Pinker knows that war, like tornadoes and tsunamis, is a fact of nature that humans are subject to. It’s probably just a fluke that some human communities don’t experience all aspects of human nature. Biology can be funny sometimes.

After all, I come from a part of the world in which no one can remember any tsunamis. But that doesn’t meant that tsunamis aren’t real.

I assume the argument of the Bellicose School would go something like that. I don’t know, to be honest. I’ve never met a committed member of the Bellicose School in real life. They’re rare in the wild, but surprisingly prevalent at the highest levels of academia. Promoting the type of ideology that the rich want to believe is a good career move for amoral academics with low ethical standards.

This couldn’t have anything to do with the fact that academia exists to convince people that the socioeconomic reality that they were born into is the best of all possible worlds, and that challenging it is stupid because everyone knows that humans are nasty, endlessly-feuding brutes.

That’s what passes for higher learning in our world - learning the Hobbesian prejudices of the ruling class.

I say FUCK THAT! The reason that they think this way is because they (correctly) surmise that we are in the midst of a war - a class war. The ruling class think that humans are warlike because they cannot imagine not having the privilege and power that they have in the modern world, and that privilege and power comes from the economic exploitation of the working class. They hate humanity because they (rightly) perceive the masses as a threat. But there’s no reason the rest of us should share their prejudice. They are afraid of us because they are our enemies. But are we are our enemies? Maybe some of us are, but I’m not. I’m a big believer in being on your own side. If you aren’t on your own side, why should anyone else be?

This is called class consciousness, and it is a big part of what woke ideology, including feminism, seeks to quell and contain. Class consciousness leads inexorably to what I call “enlightened self-interest”, which involves a type of comradely or neighbourly solidarity for the simple reason that life is better without enemies.

Humans beings made often be stupid, lazy, smug, susceptible to groupthink, vain, presumptuous, or annoying, but most of them really aren’t very violent at all. To be honest, most people are cowards. Furthermore, studies have shown that most soldiers need to be indoctrinated with nationalistic propaganda in order to actually kill enemy soldiers - otherwise they will shoot to miss, presumably preferring not to take on the karmic consequences of killing a stranger, who is, after all, someone’s son.

Anyway, at the end of the day, I’m 5’7, 170 pounds and 36 years old and I can still kick most people’s asses.

If humans were as naturally violent as Richard Wrangham would have you believe, human beings would be better at violence.

I rest my case.

for the Wild,

Crow Qu’appelle

Savaging Primitives: Why Jared Diamond’s “The World Until Yesterday” is Completely Wrong

By Stephen Corry, Director-General of Survival International from 1984 to 2021

I ought to like this book: after all, I have spent decades saying we can learn from tribal peoples, and that is, or so we are told, Jared Diamond’s principal message in his new “popular science” work, The World Until Yesterday. But is it really?

Diamond has been commuting for 50 years between the U.S. and New Guinea to study birds, and he must know the island and some of its peoples well. He has spent time in both halves, Papua New Guinea and Indonesian‐occupied West Papua. He is in no doubt that New Guineans are just as intelligent as anyone, and he has clearly thought a lot about the differences between them and societies like his, which he terms Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (“WEIRD”). He calls the latter “modern.”

Had he left it at that, he would have at least upset only some experts in New Guinea, who think his characterizations miss the point. But he goes further, overreaching considerably by adding a number of other, what he terms “traditional” societies, and then generalizing wildly. His information here is largely gleaned from social scientists, particularly (for those in South America) from the studies of American anthropologists, Napoleon Chagnon, and Kim Hill, who crop up several times.

It is true that Diamond does briefly mention, in passing, that all such societies have “been partly modified by contact,” but he has still decided they are best thought about as if they lived more or less as all humankind did until the “earliest origins of agriculture around 11,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent,” as he puts it. That is his unequivocal message, and the meaning of “yesterday” in his title. This is a common mistake, and Diamond wastes little of his very long book trying to support it. The dust jacket, which he must agree with even if he did not actually write it, makes the astonishingly overweening claim that “tribal societies offer an extraordinary window into how our ancestors lived for millions of years” (my emphasis).

This is nonsense. Many scientists debunk the idea that contemporary tribes reveal anything significantly more about our ancestors, of even a few thousand years ago, than we all do. Obviously, self-sufficiency is and was an important component of the ways of life of both; equally obviously, neither approach or approached the heaving and burgeoning populations visible in today’s cities. In these senses, any numerically small and largely self-sufficient society might provide something of a model of ancient life, at least in some respects. Nevertheless, tribal peoples are simply not replicas of our ancestors.

Britain’s foremost expert on prehistoric man, Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum, for example, routinely cautions against seeing modern hunter-gatherers as “living fossils,” and repeatedly emphasizes that, like everyone else, their “genes, cultures and behaviors” have continued to evolve to the present. They must have changed, of course, or they simply would not have survived.

It is important to note that, although Diamond’s thesis is that we were all once “hunter-gatherers” and that this is the main key to them being seen as our window into the past, in fact most New Guineans do little hunting. They live principally from cultivations, as they probably have for millennia. Diamond barely slips in the fact that their main foodstuff, sweet potato, was probably imported from the Americas, perhaps a few hundred or a thousand years ago. No one agrees on how this came about, but it is just one demonstration that “globalization” and change have impacted on Diamond’s “traditional” peoples for just as long as on everyone else. Disturbingly, Diamond knows these things, but he does not allow them to spoil his conclusions.

But he has come up with a list of practices he thinks we should learn from “traditional” societies, and all this is well and good, though little of it appears particularly radical or novel. He believes we (Americans, at least) should make more effort to put criminals on a better track, and try to rehabilitate rather than merely punish. He feels we should carry our babies more, and ensure they’re facing forward when we cart them around (which is slightly odd because most strollers and many baby carriers face forward anyway). He pleads with us to value old people more … and proffers much similar advice. These “self-help manual” sections of the book are pretty unobjectionable, even occasionally thought-provoking, though it is difficult to see what impact they might really have on rich Westerners or governments.

Diamond is certainly in fine fettle when he finally turns to the physiology of our recent excessive salt and sugar intake, and the catastrophic impact it brings to health. His description of how large a proportion of the world is racking up obesity, blindness, limb amputations, kidney failure, and much more, is a vitally important message that cannot be overstressed. Pointing out that the average Yanomami Indian, at home in Amazonia, takes over a year to consume the same amount of salt as can be found in a single dish of a Los Angeles restaurant is a real shocker and should be a wake-up call.

The real problem with Diamond’s book, and it is a very big one, is that he thinks “traditional” societies do nasty things which cry out for the intervention of state governments to stop. His key point is that they kill a lot, be it in “war,” infanticide, or the abandonment, or murder, of the very old. This he repeats endlessly. He is convinced he can explain why they do this, and demonstrates the cold, but necessary, logic behind it. Although he admits to never actually having seen any of this in all his travels, he supports his point both with personal anecdotes from New Guinea and a great deal of “data” about a very few tribes—a good proportion of it originating with the anthropologists mentioned above. Many of his boldly stated “facts” are, at best, questionable.

How much of this actually is fact, and how much just personal opinion? It is of course true that many of the tribes he cites do express violence in various ways; people kill people everywhere, as nobody would deny. But how murderous are they exactly, and how to quantify it? Diamond claims that tribes are considerably more prone to killing than are societies ruled by state governments. He goes much further. Despite acknowledging, rather sotto voce, that there are no reports of any war at all in some societies, he does not let this cloud his principal emphasis: most tribal peoples live in a state of constant war.

He supports this entirely unverifiable and dangerous nonsense (as have others, such as Steven Pinker) by taking the numbers killed in wars and homicides in industrialized states and calculating the proportions of the total populations involved. He then compares the results with figures produced by anthropologists like Chagnon for tribes like the Yanomami. He thinks that the results prove that a much higher proportion of individuals are killed in tribal conflict than in state wars; ergo tribal peoples are more violent than “we” are.

There are of course lies, damned lies, and statistics. Let us first give Diamond the benefit of several highly debatable, not to say controversial, doubts. I will, for example, pass over the likelihood that at least some of these intertribal “wars” are likely to have been exacerbated, if not caused, by land encroachment or other hostilities from colonist societies. I will also leave aside the fact that Chagnon’s data, from his work with the Yanomami in the 1960s, has been discredited for decades: most anthropologists working with Yanomami simply do not recognize Chagnon’s violent caricature of those he calls the “fierce people.” I will also skate over Kim Hill’s role in denying the genocide of the Aché Indians at the hands of Paraguayan settlers and the Army in the 1960s and early 1970s. (Though there is an interesting pointer to this cited in Diamond’s book: as he says, over half Aché “violent deaths” were at the hands of nontribals.)

I will also throw only a passing glance at the fact that Diamond refers only to those societies where social scientists have collected data on homicides, and ignores the hundreds where this has not been examined, perhaps because—at least in some cases—there was no such data. After all, scientists seeking to study violence and war are unlikely to spend their precious fieldwork dropping in on tribes with little noticeable tradition of killing. In saying this, I stress once again, I am not denying that people kill people—everywhere. The question is, how much?

Awarding Diamond all the above ‘benefits of doubt’, and restricting my remarks to looking just at “our” side of the story: how many are killed in our wars, and how reasonable is it to cite those numbers as a proportion of the total population of the countries involved?

Is it meaningful, for example, to follow Diamond in calculating deaths in the fighting for Okinawa in 1945 as a percentage of the total populations of all combatant nations—he gives the result as 0.10 percent—and then comparing this with eleven tribal Dani deaths during a conflict in 1961. Diamond reckons the latter as 0.14 percent of the Dani population—more than at Okinawa.

Viewed like this, the Dani violence is worse that the bloodiest Pacific battle of WWII. But of course the largest nation involved in Okinawa was the U.S., which saw no fighting on its mainland at all. Would it not be more sensible to look at, say, the percentage of people killed who were actually in the areas where the war was taking place? No one knows, but estimates of the proportion of Okinawa citizens killed in the battle, for example, range from about 10 percent to 33 percent. Taking the upper figure gives a result of nearly 250 times more deaths than the proportion for the Dani violence, and does not even count any of the military killed in the battle.

Similarly, Diamond tells us that the proportion of people killed in Hiroshima in August 1945 was a tiny 0.1 percent of the Japanese people. However, what about the much smaller “tribe” of what we might call “Hiroshimans,” whose death toll was nearly 50 percent from a single bomb? Which numbers are more meaningful; which could be seen as a contrivance to support the conceit that tribespeople are the bigger killers? By supposedly “proving” his thesis in this way, to what degree does Diamond’s characterization differ significantly from labeling tribal peoples as “primitive savages,” or at any rate as more savage than “we” are?

If you think I am exaggerating the problem—after all, Diamond does not say “primitive savage” himself—then consider how professional readers of his book see it: his reviewers from the prestigious Sunday Times (U.K.) and The Wall Street Journal (U.S.) both call tribes “primitive,” and Germany’s popular Stern magazine splashed “Wilde” (“savages”) in large letters across its pages when describing the book.

Seek and you shall find statistics to underscore any conceivable position on this. Diamond is no fool and doubtless knows all this—the problem is in what he chooses to present and emphasize, and what he leaves out or skates over.

I do not have the author’s 500 pages to expand, so I will leave aside the problem of infanticide (I have looked at it in other contexts), but I cannot omit a response to the fact that, as he repeatedly tells us, some tribes abandon, or abandoned, their old at the end of their lives, leaving them only with what food or water might be spared, and moving on in the sure knowledge that death would quickly follow, or even hastening it deliberately.

Again, Diamond explains the logic of it, and again he tells us that, because of munificent state governments’ ability to organize “efficient food distribution,” and because it is now illegal to kill people like this, “modern” societies have left such behavior behind.

Really? So let us forget the 40 million or so dead in the Great Chinese Famine of the early 1960s. But what about the widespread, though usually very quiet, medical practice of giving patients strong doses of opiates— really strong doses—when illness and age have reached a threshold? The drugs relieve pain, but they also suppress the respiratory reflex, leading directly to death. Or, what about deliberately withholding food and fluids from patients judged near the end? Specialist nonprofits reckon there are about a million elderly people in the U.K. alone who are malnourished or even starving, many inside hospitals. So how different is what we industrialized folk get up to from some tribal practices? Are we all “savages” too?

Contrasting tribal with industrialized societies has always been more about politics than science, and we should be extremely wary of those who use statistics to “prove” their views. It all depends on what your question is, whom you believe, and most of all, exactly where you are standing when you ask it.

If, for example, you are an Aguaruna Indian in Peru, with a history of occasional revenge raiding stretching back the small handful of generations which comprise living memory (no Aguaruna can really know the extent to which such raiding was going on even a few generations ago, leave alone millennia), and if you have recently been pushed out of the forest interior into riverine villages by encroachment from oil exploration or missionaries, then your chances of being killed by your compatriots might even exceed those caught in Mexican drugs wars, Brazilian favelas, or Chicago’s South Side.

In such circumstances there would undoubtedly be much more homicide in Aguaruna-land than that faced by well-heeled American college professors, but also much less than that confronted by inmates in Soviet gulags, Nazi concentration camps, or those who took up arms against colonial rule in British Kenya, or apartheid South Africa.

If you find yourself born a boy in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in the center of the world’s richest nation, your average lifespan will be shorter than in any country in the world except for some African states and Afghanistan. If you escape being murdered, you may end up dead anyway, from diabetes, alcoholism, drug addiction, or similar. Such misery, not inevitable but likely, would not result from your own choices, but from those made by the state over the last couple of hundred years.

What does any of this really tell us about violence throughout human history? The fanciful assertion that nation states lessen it is unlikely to convince a Russian or Chinese dissident, or Tibetan. It will not be very persuasive either to West Papuan tribes, where the Indonesian invasion and occupation has been responsible for a guessed 100,000 killings at least (no one will ever know the actual number), and where state-sponsored torture can now be viewed on YouTube. The state is responsible for killing more tribespeople in West Papua than anywhere else in the world.

Although his book is rooted in New Guinea, not only does Diamond fail to mention Indonesian atrocities, he actually writes of, “the continued low level of violence in Indonesian New Guinea under maintained rigorous government control there.” This is a breathtaking denial of brutal state-sponsored repression waged on little armed tribespeople for decades.The political dimensions concerning how tribal peoples are portrayed by outsiders, and how they are actually treated by them, are intertwined and inescapable: industrialized societies treat tribes well or badly depending on what they think of them, as well as what they want from them. Are they “backward,” from “yesterday”; are they more “savage,” more violent, than we are?

Jared Diamond has powerful and wealthy backers. He is a prestigious academic and author, a Pulitzer Prize winner no less, who sits in a commanding position in two American, and immensely rich, corporate-governmental organizations (they are not really NGOs at all), the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Conservation International (CI), whose record on tribal peoples is, to say the least, questionable. He is very much in favor of strong states and leaders, and he believes efforts to minimize inequality are “idealistic,” and have failed anyway. He thinks that governments which assert their “monopoly of force” are rendering a “huge service” because “most small-scale societies [are] trapped in … warfare’ (my emphasis). “The biggest advantage of state government,” he waxes, is “the bringing of peace.”

Diamond comes out unequivocally in favor of the same “pacification of the natives,” which was the cornerstone of European colonialism and world domination. Furthermore, he echoes imperial propaganda by claiming tribes welcome it, according to him, “willingly abandon[ing] their jungle lifestyle.”

With this, he in effect attacks decades of work by tribal peoples and their supporters, who have opposed the theft of their land and resources, and asserted their right to live as they choose—often successfully. Diamond backs up his sweeping assault with just two “instances”: Kim Hill’s work with the Aché; and a friend who recounted that he, “traveled half way around the world to meet a recently discovered band of New Guinea forest hunter-gatherers, only to discover that half of them had already chosen to move to an Indonesian village and put on T- shirts, because life there was safer and more comfortable.”

This would be comic were it not tragic. The Aché, for example, had suffered generations of genocidal attacks and slavery. Was Diamond’s disappointed friend in New Guinea unaware of the high probability of carrying infectious diseases? If this really were a recently “discovered” band, which is highly unlikely, such a visit was, to say the least, irresponsible. Or, was it rather a contrived tourist visit, like almost all supposed “first contacts” in New Guinea where a playacting industry has grown up around such deception? In either event, West Papuans are “safer” in Indonesian villages only if they are prepared to accept subjugation to a mainstream society which does not want them around.

As I said, I ought to like this book. It asserts, as I do, that we have much to learn from tribal peoples, but it actually turns out to propose nothing that challenges the status quo.

Diamond adds his voice to a very influential sector of American academia which is, naively or not, striving to bring back out-of-date caricatures of tribal peoples. These erudite and polymath academics claim scientific proof for their damaging theories and political views (as did respected eugenicists once). In my own, humbler, opinion, and experience, this is both completely wrong—both factually and morally—and extremely dangerous. The principal cause of the destruction of tribal peoples is the imposition of nation states. This does not save them; it kills them.

Were those of Diamond’s (and Pinker’s) persuasion to be widely believed, they risk pushing the advancement of human rights for tribal peoples back decades. Yesterday’s world repeated tomorrow? I hope not.

You wrote "Stephen Fry, by the way, is the author of Beyond War...". I think you meant Douglas ;-)