The below essay is by Zac Hyden at Mechonomist. He is an auto mechanic and community organizer in Alabama who is also currently the Campaign Manager for Ryan Cagle in his race for a State Senate seat. Zac has been hanging out in Nevermoreland lately. He gives us a thoroughgoing reinterpretation of the American South here. It’s got rednecks, dysfunction, redemption, and revolutionary potential galore. The logo for his car repair co-op heads this post. Somehow, getting your hands dirty repairing folks’ broken-down, dysfunctional, vehicles at cost also strikes me as rednecky, redemptive, and revolutionary. (WD James, ed.)

For Hank, my son

Written on a Harbor Freight, Icon brand T8 Scan Tool

One of my favorite songs is Song of the South, a rousing Southern anthem which fuses hardship with pride, covered by Alabama from 1989. It’s one of those tunes that resonates in a way that is beyond explanation, that makes you think of your kind mother and abusive father, fireflies on hot summer nights, the Iron Bowl, sweet tea, sweet potato pie (in response to which, as Alabama’s Randy Owens sings, “I’ll shut my mouth”).

This essay is written in this spirit. I want to tell a new story about the American South that is somehow so old that it seems like common sense. It’s a story about class and race and sex. It’s about the messy complexity that is never far below the surface of everything in my home, as mundane as food and as epic as our politics. I love my home, my son and my wife, and my son and my wife and my home are all part of the same glorious whole.

Ultimately, this is my story and my story alone. I don’t speak for all of the American South, or for all working class whites, for rednecks, for liberals or conservatives, communists or anarchists. I don’t steal from the stories of Black people, of lynching, slavery, and struggles. It’s not a grand narrative; it’s my narrative, a take on the land and people that I love so dearly that I’d give up everything for them. To speak for others would rob them of their independence and autonomy, so cherished by Southernners of all flavors and rooted in our Irish past, maybe, or perhaps we invented it. Does it really matter? Nope!

I don’t take my story directly from the Civil Rights Movement, not because it wasn’t important, but because that story has been told by so many that it’s become marketing gold and resistance poo-poo, like Smiley in Do the Right Thing, twisted and distorted and on sale for two dollars a pop. No, my story is that of pirates and rebels and deviants and friends, a story less often told about the South and not often sold, but told in bars, billiard rooms, Pentecostal Churches, shops, racetracks, tailgates, but never, ever at the country club because the people at the country club have yet to hear it but maybe they will hear the thoughts in this essay and make it theirs because they make everything theirs; see the Civil Rights Movement.

But, before this story begins, I must warn you, it’s all lies because the Southern tradition is always to tell lies and in the pirate tradition is that you can always trust a dishonest person to be dishonest, and I’m dishonest.

I was born at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama on August 31st, 1978, the same year that the city’s first Black mayor was elected and a few years before George Wallace was re-elected governor with 90% of the Black vote. I grew up in the Church of Christ which is a rigidly fundamentalist Christian denomination with great music. My dad was a preacher in that church, but he was also a brutal man who terrorized me as a child.

I used to connect my father’s brutality to the Church. My first memory of my father is being tossed around my bedroom by him in a fit of rage. I was probably 6. I remember thinking that being flung around like that was kinda fun, which was probably a 6 year old’s version of self preservation. It stopped when my dad hit my head on the cross bar of a bunk bed and started laughing. I don’t know why he was laughing, but I started laughing to because I guess I knew he loved me and would never hurt me. The rest of my childhood would be his discipline backed by the threat of his rage.

I used to think that my father was the way that he was because he believed in a faith that was fundamentally brutal. The Church of Christ fucks up a lot of people because it is rigidly patriarchal in an increasingly girl-boss world. The Church of Christ is a mismatch for many, particularly women with certain types of aspirations, queer people, artists, thinkers, deviants, and pirates. The mismatch between what the Church wants and what pirates desire causes the pain of believing that you’re betraying your homes and traditions. Nonetheless, the Church works as a worldview and a way of life for millions in the South and none of this is insignificant.

I used to think my father was the South, that the South was brutal and that he was brutal because the South was brutal to him, but I’ve since learned that the South is not one thing or even several things or anything at all beyond ideas imposed from elsewhere. In the struggle to define ourselves we often adopt stereotypes imposed by Yankees, instead of crafting our own story that is neither defined by our own brutality or the brutality of the definitions imposed on us. This is harder than it looks.

My dad was bad to me because he was a fucked up dude, not because of the South or any weird shit like that. There are fucked up dudes everywhere in the world, which is another story that I’ll probably get to, and that fuckedness gets run through a culture, but it’s not because of the culture. My dad’s behavior was his and only his responsibility.

Like any good Southerner, I grew up on college football. In Alabama, you’re either an Auburn fan or an Alabama fan and people look at you sideways if you don’t choose or say “Tennessee.” Our family - Auburn fans. Hal, my father, was an Auburn alumnus, the first in his family to graduate college. I would eventually follow him there. One of my first memories was “Bo Over the Top,” when Auburn and Bo Jackson beat Alabama in the Iron Bowl for the first time in so many years. Bo Jackson is a sort of legendary, Paul Bunyan type character in Alabama who was said to have once jumped over a Volkswagen flat footed. He played at McAdory High School, which was just around the corner from my parents house outside Bessemer, pronounced Bessma. I also saw another legendary Auburn man play at McAdory - Bo Nix, the son of Patrick Nix, former Auburn QB and Iron Bowl hero who obviously named his son after Bo Jackson. Everything connects and connects with a kind of poetry and rhythm in the South.

Like Bo, I was a gifted child or at least everyone thought I was. My IQ tested at 162 at 6 and my childhood basically ended. My parents saw intelligence as a means to success, when in reality, late capitalism rewards mediocrity much more than intelligence. I was tracked into advanced courses and set on a path towards college and wealth beyond imagination, which at the end of the day was the only thing my father valued. I don’t know if I was really that intelligent or if, because of that stupid test, I was forced to be a genius, which I am and I acknowledge that I am, but I do so not arrogantly, but rather, with regret. To be a sensitive, creative thinker with a tyrannical father and to have no mentors (at least not until later in life) made for a very sad childhood.

My childhood was miserable, but it wasn’t without its hopeful moments. When I was 12, my father coached my Pony League baseball team and we went all the way to the finals. He was publicly funny and charismatic, which was such a stark contrast to my father at home. I wanted to play for him as did all my teammates. He was truly a special man, but very tortured. He knew people, deeply, but he didn’t know himself very well. I played catcher and didn’t strike out all season. I broke my foot playing basketball in the front driveway and unfortunately couldn’t finish the season. We lost in the championship. Even the one great story from my childhood is tinged with minor tragedy. Such is the American South.

Maybe, though, my father wasn’t the South at all. Instead, he was a Southern-born Yankee who valued money over community and conformity over eccentricity. Maybe, like Yankees all over the world, if this Southern boy didn’t follow all the rules of capitalism and modernity, he was doomed to be punished and not celebrated. And maybe this essay is an attempt to reclaim my Southernness from all Yankees.

My last memory of my father was when he called me on Father's Day to tell me he loved me. He died of suicide a week later and a little over a year after I published my memoir, which talked about my father’s abuse and rage. I will always believe that that book played some role in my father’s suicide and it is and will be a burden I carry for the rest of my life. I have blood on my hands. I didn’t pull the trigger, but I did give him the gun.

A People’s History of the American South

Telling history is a subjective art. All history is revisionist and reflects present conditions less than those of the past. The problem of the South that must forever be solved is the problem of race.

Race is a quintessentially historical and geographic project designed to ensure that the working class focuses more on differences than on commonalities and mutual self-interest. The point of the racial project is to produce antipathic subjectivities among people with different histories and cultures and to produce different histories and cultures by separating these subjectivities in time and space. This began with slavery and continues to this day in complicated ways.

Enslaved people were separated by the division between the big house and the slave house. This enforced the difference in subjectivity between affluent white planters and enslaved Africans. Poor whites were also separated spatially from the big house by working on small farms (or even on the plantation) as wage laborers and living separately from both enslaved populations and planters. Instead of two divisions as is commonly assumed, there are three and there continue to be three, two of which are quasi-wedded through the ideology of white supremacy but not in space or historicity. There were enslaved populations with erased culture and history and spatially separate; poor whites with a racialized history, yet contradictorily spatially separate; and, at the center of Southern society, Bourbon Planters.

The alliance between poor whites and planters through the bonds of whiteness has at times been strong and at other times been quite tenuous. Yet, the allegiance of poor whites to the planters has always been the lynch pin of Southern society and during the times in which this alliance has broken down, such as during and after the Civil War, the planters (and later the industrialists) have doubled down on white supremacy. The key to a revolutionary South is thus the class consciousness and allegiances of poor whites. The revolution is redneck.

We must tell a history of the South that reveals this revolutionary instinct among rednecks. The beginning of this history is totally arbitrary. It could be the Civil War where 250,000 poor whites, almost one quarter of the Confederate army, deserted. Or the Populist Movement where Black and white workers rebelled against the planters for 20 years leading planters to create the Jim Crow system. Hell, we can even point to art movements like Outlaw Country which enshrined the resistance narrative in redneck culture.

Redneck History: The Civil War

I choose to start this History of rednecks with the Civil War for a few reasons. Though Bacon’s Rebellion could be posited at the beginning but the rebellion has been romanticized to the point that the story no longer even closely resembles the actual facts on the ground, which had much less clarity on motivations and purpose of the warring factions than just an alliance of diverse bond-servants. The other is that many rednecks posit their history as beginning in resistance to an invading Northern army, a claim which I take seriously and don’t dismiss out of hand. The identification by rednecks with the Confederate army has developed over recent years, but did such identification always exist?

The answer clearly is a resounding “no.” 250,000 poor whites deserted the Confederate army during the war, one of the major causes of the fall of slavocracy. In the common understanding, the Civil War was a battle between the virtuous North freeing the slaves from the evil South with little differentiation between factions of people in either area. In fact, the great myth-making of Lincoln freeing the slaves is wholly untrue because his Emancipation Proclamation did not free enslaved people in the border states. Furthermore, this move wasn’t moral but practical. He needed more troops and he correctly calculated that if he did the Emancipation Proclamation, Northern Black people would swell the ranks of the Union Army and turn the tide of the war. He was right and the Black revolutionary force along with the Southern deserters won the war and ended formal slavery.

The myth-making about Yankees goes on to argue that the North was virtuous while the South was deviant by arguing that the war itself was for virtuous reasons, but like all wars, “war ain’t about one land against the next, it’s poor people dying so the rich cash checks” in the words of Hip Hop artist Boots Riley.

If looked at globally instead of provincially and jingoistically, the South appears as an internal colony of the United States with Southern colonial administrators (Southern Yankees) and Northern industrialists (Northern Yankees) benefiting from cheap raw materials and labor provided by the slavocracy. Few Southerners owned enslaved people and even fewer had any connection whatsoever to large plantations where most of the enslaved people were captives. The vast majority of these plantations existed in the Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta and the governments of the South were controlled by these wealth centers. It strains credulity to believe that a poor hog farmer in Southern Appalachia shared any interests whatsoever with a wealthy Bourbon Planter and the desertion from the Confederate Army along with the pockets of resistance to the Confederacy within Appalachia would suggest that, when push came to shove, they didn’t. White supremacy is and was always a tenuous bargain for the working class.

Simply put, Northern industrials invaded the territory of colonial administrators - planters - because of the planters’ economic advantage of enslaved labor. It was a fratricidal, rich man’s war won by a Black revolutionary force that freed enslaved people. It was aided by rednecks’ refusal to fight for the South. When it came to brass tacks, when lives were on the line, rednecks and the Black proletariat were on the same side.

Redneck History: The Populist Movement

The populist movement in Alabama during the 1880s and 1890s was a firestorm that swept across the state, fueled by the frustrations and anxieties of farmers and workers. At its core, the movement was a rebellion against the entrenched powers of wealth and privilege, which had long dominated the state’s politics and economy.

For decades, Alabama’s farmers had struggled to make ends meet, plagued by low crop prices, high interest rates, and exploitative practices by railroads and other corporations. The state’s workers, meanwhile, toiled in miserable conditions for meager wages, with little protection from the ravages of industrial capitalism.

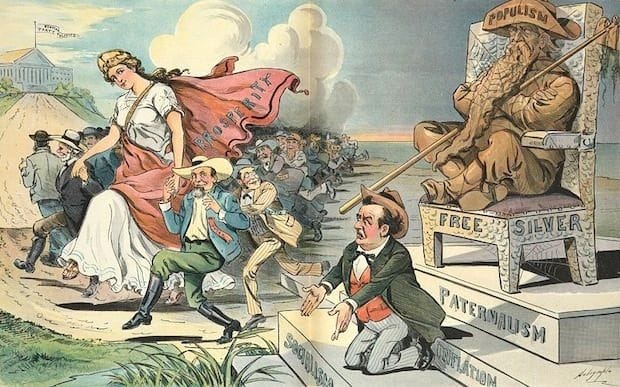

Into this cauldron of discontent, the populist movement burst forth, promising to shake the very foundations of Alabama’s power structure. Led by fiery orators and organizers like Reuben Kolb, the populists rallied farmers and workers, both Black and white, around a bold platform of reform.

At the heart of the populist agenda was the demand for railroad regulation. For years, Alabama’s railroads had gouged farmers and workers with exorbitant rates, siphoning off their hard-earned profits and leaving them destitute. The populists vowed to put an end to this exploitation, calling for the creation of a state railroad commission to regulate rates and ensure fair treatment for all.

The populists also championed the cause of progressive taxation, arguing that the wealthy elite should be forced to pay their fair share of the tax burden. For too long, Alabama’s tax system had been rigged in favor of the rich, with the poor and middle class shouldering a disproportionate share of the load. The populists demanded a more equitable system, one that would require the wealthy to contribute to the state's coffers in a meaningful way.

Another key plank of the populist platform was the creation of a state bank, which would provide low-interest loans to farmers and workers. For years, Alabama’s farmers had been forced to rely on predatory lenders, who charged usurious interest rates and drove them deeper into debt. The populists vowed to put an end to this exploitation, creating a state bank that would offer fair and affordable credit to those who needed it most.

Despite its many successes, the populist movement in Alabama ultimately fell short of its goals. The movement was undermined by internal divisions and conflicts, as well as by the fierce opposition of the state’s wealthy elite. In the end, the populists were unable to overcome the entrenched powers of privilege and wealth, and their movement slowly faded away.

Yet, despite its ultimate defeat, the populist movement in Alabama left a lasting legacy. It helped to galvanize a new generation of progressive activists, who would go on to fight for reform and justice in the decades to come. And it reminded the people of Alabama that, even in the darkest of times, there is always the possibility for change and transformation.

The Alabama Redeemer Constitution was the planters and industrialists’ response to the Populist Movement. It was designed to enshrine white supremacy legally and as the backbone for the future Jim Crow Regime. It centralized power in the state government, which disenfranchised local governments and made control of state governments easy for planters and industrialists. It also created all sorts of disenfranchising legal structures like poll taxes and literacy tests. Later, the Jim Crow Regime would spatially divide workers into Black and White communities and cultivate oppositional subjectivities by celebrating the Civil War and the so-called “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” as Southern history. It is important to know that while the Jim Crow Regime was tactically racial, it was strategically classist precisely because of the lingering threat of the Populist Movement.

Redneck History: Jim Crow

The tragedy of Jim Crow is that a) it has never died or been defeated and b) it has worked so incredibly well. It divided the working class so well that subjectivities that were different but similar became so different that the Black and white proletariats in the South live in essentially different worlds and the antipathy on both sides is palpable in day to day life. This capitalist strategy of division was and is accomplished through a total societal system of legal, cultural, and economic Jim Crow. Southern society is based on dividing people into Black and white and has been in this iteration since the end of the Populist Movement.

I was a community organizer in Birmingham, Alabama for seven years. It was difficult. People never trusted me fully and expected me to make sacrifices that I did in fact make but shouldn’t have. Routinely, Black people in Birmingham would reference sundown towns as if going to small rural towns that were mostly, but not completely, white was remarkably dangerous, something akin to the height of Jim Crow and the Klan. The collective memory of those places is one of danger even if that danger no longer exists.

Similarly, people from Cullman and Clanton remark on crime in urban areas as if a Black gang member was going to jump out from behind a building and steal their 1995 Ford F150 with 300,000 miles on it. Both cultural understandings of othered places are false, but persist. Far beyond the legal structures of Jim Crow, and far more powerful, are the subjectivities created by separating in space people who have shared so much. Both of these misunderstandings are perpetuated and policed by people in each community who gain local power and notoriety by playing to their people’s baser instincts.

Jim Crow never really died either. King’s Birmingham Movement did nothing but force segregationists like Sid Smyer, revered in Birmingham because of his statement “I’m a segregationist, but I’m not a damn fool,” a sentiment shared by many of Birmingham’s leaders, the Big Mules, but not uttered in the 60s. Segregationists didn’t actually change when the structures of Jim Crow were deconstructed; they just got smarter and quieter. Nonetheless, Birmingham is still the most segregated city in the South and the well kept, fat and happy Black political class is totally beholden to these same Big Mules. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Make no mistake, the same people rule Birmingham and Alabama who have always ruled, connected to global power, but much quieter, more invisible, and a bit less violent.

Redneck History: The Battle of Blair Mountain

The term redneck has, probably apocryphally, been attributed to a five day resistance in West Virginia that was a response to the Matewan Massacre in which coal miners fought the Baldwin-Felts Detective agency. They called themselves rednecks because they wore red neckerchiefs symbolizing their solidarity and it was the second instance of an aerial bombing by the US government on American soil. The first was in Tulsa a few months earlier.

Importantly, these rednecks were not white. They were white, immigrant, and Black and they all fought together in class solidarity against the company and their thugs. I say this is important because here again we see that when the chips are down, Black and white proletariats find themselves on the same side, not at each others’ throats as our rulers would have you believe. In fact, not only are Black and white proletarians not on opposite sides, they share the same identity: redneck. This is quite important and must be explicated.

Redneck is not a racialized identity though the powerful have attempted to connect it with whiteness for generations. As my conservative friend, Joe Fontine says, “it’s a way of life” that includes deep commitment to family and community, disciplined, hard work, a kind of redneck stoicism, resourcefulness, and fairness. The stoicism part is important.

One of the tenets of stoicism is that one must accept one’s lot in life. This couldn’t be more true than it is for rednecks. A redneck is never oppressed. A redneck cannot be oppressed because a redneck is responsible for themself and for their communities and for their lot in life. If there are problems with either, it’s the rednecks’ responsibility to solve them, not slink into victimhood. There is never a person over a redneck and if there is a person who acts like they’re over a redneck, they’re likely to get an earful of colorful language or worse, possibly an ass-beating.

Objectively, I don’t think this attitude serves us all that well because clearly there are people oppressing us and our refusal to see it means that many issues in redneck communities go unaddressed either because to address them would admit victimhood or because the oppressor is of good character, meaning they know how to play all the correct cultural games.

Finally, if there are oppressors in the community like Boss Hoggs and Roscoe P. Coltrane from the Dukes of Hazzard, they must be obvious, stupid, and easily outsmarted. “Someday the mountain might get ‘em but the law never will” as Waylon so eloquently sang to us. but the notion of systems of domination that can’t be addressed directly with honesty and wit is beyond the rednecks’ cultural interpretation.

Redneck History: The Hanks

There is no singular person more important to Redneck History than Hank Williams. A crooner who sang about topics taboo in country music like drinking, cheating on your girl, premarital sex, love and loss. Hank Williams is author of what are now known as “sad country songs” in David Alan Coe’s words. Ole Hank founded the transgressive theme in country music and birthed what would later become Outlaw Country. He was fired from the Grand Ole Opry, loved Montgomery, particularly Delraida, and died young of bad habits. His romance with his wife Audrey was legendary, and his mentor, legendary bluesman Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, who also died young, is buried across the tracks in Montgomery.

Every redneck story is told the way Hank told it. Humble beginnings, rough and tumble adolescence and early adulthood, love and loss, maturity, and redemption. This is my story too, without a doubt and I imagine that on some level, it will be my son Hank’s story as well. These are the myths that we have to tell to be initiated into redneck culture and that’s just the way it is.

I’ve chosen three songs from Hank, Hank, Jr., and Hank III, father, son, and grandson of the American South to illuminate important themes in redneck culture. The first (I Saw the Light by Hank Sr.) is struggle, loss and redemption, the second (A Country Boy Can Survive by Hank, Jr.) is resiliency, and the third (Not Everybody Likes Us by Hank III) is independence.

Hank here appears as a man on his last legs. Not necessarily a bad man, but a man who’s made tons of mistakes and has many bad habits, a man who’s experienced loss. He finds God and is redeemed. There is an interesting, possibly apocryphal story of how this song came about. Apparently, Hank had been traveling and came across the hill in Prattville and saw the lights of Montgomery and exclaimed, “Praise the Lord, I Saw the Light.” The light is the light of Montgomery, my hometown, a place where the Confederacy marched up Dexter Avenue in 1860 and King marched up the same street in 1955.

This song juxtaposes the American South with the American North, the internal orient with the occident. It argues for a moral and practical superiority of the oppressed American South because we are capable of living independently, while those in the Global North do not have those same skills. It’s a tale of the superior morality of the oppressed American South.

This is one of my favorite songs ever written and could in fact be the anthem of this paper. You may not like it, but it’s going to make you crazy. Rednecks are not supposed to say these things and we’re definitely not supposed to be smart as a whip.

The American South as Internal Orient

After I graduated high school, much to the chagrin of my teachers and parents, I forewent a scholarship to David Lipscomb University, a Church of Christ school to be an automotive technician. For the next seven years, I smoked weed, drank alcohol, chased women, hung out with friends, and discovered much about myself that was suppressed by church, school and family.

I struck up a friendship with a guy named Jason Bowman over Magic: the Gathering games at the local comic shop. I also struck up a friendship with his father who I’ve grown to admire over the years. Jerry, Jason’s father, was a machinist who owned his own engraving shop that did a lot of contract work with the military. He was the model of masculinity that I truly needed. He worked hard and worked with his hands, but was kind, loving, sensitive, and had a ton of long-term friends who he valued deeply. He was and is like a father to me. What Jerry has built with his family and friends is closer to utopia than anything that I could ever imagine. This crystallized in 2020 during the pandemic and after my father died of suicide.

Mable Mountain

The South is a lot of things. It is diverse, beautiful, brutal, and kind. But, there are moments where you can see with clear eyes the inherent utopia in the Southern way. It is there. One of those moments happened at a Memorial Day gathering of old friends at a farm on a mountain outside of Guntersville, a beautiful place, God’s country. My wife and I were on the last leg of our overlanding trip across the state and I found what I’d always been looking for, which, as it usually is, was right in front of me.

Jerry is a machinist who owns a successful engraving business in Huntsville, Alabama. I’ve known him for almost 25 years and I met him in a moment when I was shaking off the trauma of my childhood. He is my model for masculinity and I admire him very much. I met him through his son, Jason, whom I’ve talked about in other places. Jerry is the type of person who is influential, but quietly so in his own loud opinionated way. People seek out his advice and his counsel, his friendship, and really his care

He built a passive solar house on his farm that my wife, Robyn, absolutely fell in love with. It’s really cool and creative and has an open air column in the center for air and heat circulation. The farm is 90 acres and covers much of the east side of Mable Mountain. He shares the property with his children and Al, a friend of close to 60 years. and his wife, Lynn. Al and his wife are Black.

Jerry’s politics can most accurately be described as Fordist liberal. Tax and spend, welfare state, education, etc, an approach that is rapidly making a comeback. His wife, Kay is a Trump supporter, mostly because of abortion. Kay is a devout Christian, while Jerry hates church, well not hates exactly, but it’s not for him.

We arrived the night before Memorial Day and talked about life and family and politics with Jerry while Kay was at work. I told Jerry that my father had killed himself. I knew the next day would be all work because if you go to Jerry’s farm, you will work. So we woke up early and helped Jerry and Kay get ready for the get together. People began arriving and the men worked outside lifting heavy shit and the women cooked. I went into the kitchen mostly because you get the greatest nuggets listening to women in the kitchen.

Lynn was clearly in charge. I haven’t been in many Black women’s kitchens in my life, but there was something definitely different about her kitchen as opposed to the ones that I’m used to. There was a slight awkwardness about it; not so much uncomfortable, but kinda like “ok, I’m not exactly sure what’s going on, but I like it.” Robyn was just vibing and it was clear that she was comfortable in a Black woman’s kitchen. This may seem like a great antiracist accomplishment, but it’s really because of privilege. She’s Vanderbilt educated in anthropology and knows how to read a room, especially a room of Black women in the South. Kay popped in from working outside and said she didn’t like vinegar in the potato salad. Yes, race was there, but it was something different. It was worthy of celebration, not divisiveness. Was there power? Of course, there always is, but that power was rooted not in political ideologies or being right; it was rooted in the bonds of relationships forged not over days, weeks, months, or even years, but over a lifetime.

Jerry pulled me aside to ask if I was alright about my father. I told him that I was estranged from my family because I would not live the rest of my life sweeping that man’s evil deeds under the rug. Jerry told me, “you can’t choose your parents, but you can choose to not be them.” A year of counseling, and Jerry brings peace to my soul in 13 words.

We ate and I DJ’d playing Gary Clark, Jr. Both Al and Jerry asked me who it was at separate moments and I think they said that it reminded them of the same artist, though I’m not sure that I remember that correctly. Can you imagine the power in that friendship, a Black and white boomer who’ve been friends since they were nine years old? Can you imagine what they’ve seen together and what they’ve experienced together? It’s a treasure and it’s fucking rare as chicken’s teeth.

The family that Jerry and Kay and Al and Lynn have built together is what the South could be. There are Trump supporters, white liberals, Black people, and even a dyed in the wool revolutionary, but none of that shit matters. All that matters is the relationships forged over decades of life and death, of being there for each other no matter what the odds or obstacles. That my friends is the utopia of the Southern way, and I never wanted to leave.

Yet, this story is never told. The story of Southern peace and patience, of healthy masculinity, of life-long cross racial friendships, of diversity. The failure to tell this story must be named and defined. That process of telling the story of the South as a place of lack and deviance is called internal orientalism.

Orientalism is a concept developed by Palestinian author Edward Said. He argued that the Global South was constructed as deviant and backwards as a way to construct a virtuous Global North and to act as cover and justification for the exploitation of the Global South by the Global North. In the United States context, narratives about the American South being backwards and deviant serve as justification for the exploitation of American South labor and natural resources by Transnational Corporations and particularly private equity.

Mable Mountain is the actual South. The internal orientalized South is the Redneck Horror of Northwest Georgia in the film Deliverance.

Deliverance is a story of civilized urban men traveling to a rural area outside of Atlanta to conquer it. The film is supposed to be an allegory for nature fighting back against exploitation, but it instead merely characterizes rural people as alternatively sexually violent, backwards, and deviant or as overly kind and hospitable. None of the Southern characters have any depth or complexity. They’re presented as little more than animals.

As a film it reinforces well worn orientalizing narratives of the American South—that it is backwards, close to nature, violent, sexually deviant, and exotic—much like the characterization of the Global South by the Global North. While the film is attempting to show the moral failure of modernity, it in fact only reinforces modern life’s rhetorical dominance over the American and Global South. The American South is many things, like all places, but its utopia does exist on Jerry Bowman’s Mable Mountain, which though geographically identical to the mountains of Deliverance, is an entirely different world. .

The other piece to internal orientalism is material for which the rhetorical provides cover for exploitation. In Alabama, my home, the most profitable industry is timber. Our only billionaire, Jimmy Rane, and he’s not quite a billionaire yet, is a timber baron. 70% of all land in Alabama is in timber and in a shocking number, 62% is absentee owned, often by private equity in Manhattan. The other major industry in Alabama is manufacturing, which is almost completely deunionized, exploiting Alabamian labor for the profit of Transnational corporations.

Even the stories told about the Civil War, about a virtuous North battling a deviant South, with little nuance serve orientalizing purposes. Together with the argument that Jim Crow was about racial hatred and the more modern divisive discourses, and the narrative and material landscape seems almost impenetrable to those of us who want our home to be better and who truly love it. The basic mechanics of this is to erase class in favor of race and divide, divide, divide.

The South’s Revolutionary Future

All of this is the backdrop for current conditions in the American South and really the globe. Problems that were once local are now inescapably global and the Global condition is one of collapse. Collapse of global empire and global ecosystem collapse. Capitalism cannot sustain and a new system must be created. I believe this and I believe the American South can be ground zero for creating such a system because it’s close enough in proximity to the Empire to have some resources and far enough away to break away. In addition, redneck culture is uniquely positioned to build the institutions necessary to survive collapse.

The world could break a couple of ways. There could be a great Global awakening where leaders realize that they’re going to have unlimited power over a pile of ashes. I’m not optimistic that this will happen. What is more likely is that the state gets paired down to its basic functions—supporting an increasingly distant capital and policing. The vast majority of people will be left to fend for themselves. This is where we kind of are anyway as the proliferation of budding institutions of mutual aid attests to. But, these institutions and networks of organizations lack a unifying framework and I believe that framework to be an ethical one.

Rednecks are tough and independent. Rednecks are tough people. We’ve survived poverty, the Civil War, the Great Depression, the opiate crisis, racism, bigotry, and just about anything else thrown at us individually or collectively. This toughness has to be embodied by new institutions. If there is one thing about the future that is certain is that it will be tougher, much more difficult than the past. “We can skin a buck and run a trot line; a country boy can survive.”

The mendacity of modern institutions must cease. The desire by modern leaders to perpetuate their power by weaving webs of lies and deception is a gigantic barrier to addressing collapse and during and post-collapse institutions must be founded on telling the truth as it sees it to the people it serves no matter how difficult that is. The problem with this is most people want to be told a comforting lie over a harsh truth. Harsh truths are coming one way or the other. Honesty and forthrightness is a key redneck value.

Rednecks can do just about anything. My friend Joe Fontine is a plumber, electrician, roofer, auto mechanic, and carpenter. Resourcefulness and resilience is also a redneck value and a quality that must be inculcated by institutions. Modern institutions value the specialized pushing of paper when we need diverse hard skills like the skills of Papa Joe.

One of my redneck friends says “friendship is security.” Americans don’t have friends and many familial relationships are strained. Researchers argue that it is impossible to maintain friendships with more than 100 people. This seems like an astronomical number in comparison to the number of friends Americans actually have. Friendships are not based on ideological purity, intelligence, skills, and any form of transaction, but of one thing—care for one another. That is, in a word, love.

The final redneck value is freedom, which cannot, and should not be explained because freedom explained for one person or group is oppression to another.

On top of these values, four institutions must be built—mutual aid, cooperatives, unions, and popular education. I could go on and on about what these should be, but luckily for us, they exist in Alabama and telling the story of how these came into being will serve to demonstrate what new institutions, what new redneck time and space must look like.

We began working on cooperatives in Birmingham, Alabama in 2010 when a queer activist, Anna McCown, a Black woman community leader, Virginia Ward, and I founded Magic City Agriculture Project, a community development and antiracist organization. Our first project was to aid Ms. Ward’s church, Hopewell Missionary Baptist Church, in starting a community garden in the Grasselli neighborhood, a poor, almost exclusively Black community.

We had exactly zero idea what we were doing, but we were doing it with more and more people including hiring an executive director, Rob Burton and continuing to promote gardening in the city. We also engaged in antiracist activism online and held antiracist training.

Almost all this shit was remarkably stupid, particularly the antiracist stuff. I was doing interviews and panels about race all over the city, making a big name for myself by calling everyone and their mother privileged. In retrospect, it’s kinda funny—this bearded, redneck Berkeley radical running around a Black city playing hero ball on race. I regret most of it, but it did endear me to Black people. White people hated me.

And that’s the rub; antiracism is great to Black people but terrible to white people, the people we’re supposedly trying to convert and it is conversion. Antiracism is more akin to religion than to a scientific philosophy, complete with sinners and saints, saviors, Pharisees, and Rome. The only unforgivable sin is being a white man and it’s not even a behavior. White men are the original sinners.

The crazy thing is that for all the bull in the China shop activism, my alcoholism, and just overall braindeadness, we did manage to get a mayor elected, Randall Woodfin. By 2017 our and others organizing had grown to include a number of different organizations including Black Lives Matters-Birmingham (tha’st a-whole-nother story that I’ll tell you sometime) and the coalition got behind a young attorney who reached out to Rob and I in 2015 about a plan we created for cooperatives in Birmingham. Randall got elected, turned on us immediately after inauguration, and the rest of that sorry ass story is history.

I moved to Montgomery, got out of organizing and went back to work as an automotive technician, never intending to get into politics again.

Paradoxically, going back into the shop was the best thing that ever happened to me politically. I learned that all the ideologies and philosophies that I held so dear not only never made it to the shop floor, but also, in the few instances that they did, they were resoundingly derided. That’s not to say that us rednecks had nothing to say. In fact, much of this article is an attempt to take what rednecks say and turn it into a systemic philosophy of liberation. One of the main things that we say, half joking, is that auto mechanics are essentially “peasants.”

My friend Neil said this to me one night while we were all in his backyard, they were drinking, and we were all tinkering around with some shit-box. Neal is an ASE certified master automotive technician and a sort of mechanic guru to me. I was way behind after getting out of the industry for 11 years and Neal was pivotal in me getting caught up because the technology had changed a ton.

Anyway, Neal said that mechanics were “peasants,” which I don’t know if he’s done a deep dive into anthropologist Eric Wolf’s work, but the metaphor is apt. Technicians are skilled laborers, fully integrated into the modern world, have a measure of financial independence, and are deeply misunderstood and resoundingly shit on by society. All this is to say that redneck is a big category politically, but at least some of us are peasants.

In the years that I worked at the Toyota dealership with Neal, I began to critique anti-racism and critical race theory. I also began deconstructing my work in Birmingham, what we did and why it all went down in such a fucked up way. I came to a few conclusions:

I helped everyone but myself and my own people.

I acted like a white savior.

I abandoned Marxist principles in favor of identity politics. Because of this, I failed to do an accurate material analysis on Randall Woodfin, instead believing that because he was a young, Black man, he was on our side. Woodfin was a prosecutor before being elected mayor.

Because I had essentially no principles whatsoever, I opened myself to being used and manipulated by all sorts of nefarious political agents.

Critical race theory (CRT) does not work logically or as a movement ideology.

I guess I have to defend this last fucking claim, but I’m going to do it with as few words and efficiently as possible. There’s no such thing as a “white person.” It is an empirically unverifiable category. If there is no such thing as white people, then there can be no such thing as whiteness or white dominant culture or whiteness and by extension Blackness has nothing to do with skin color at all and are simply names for types of culture. It cannot be argued that rednecks, who are racialized white, have a dominant culture of any kind since we are thoroughly dominated and the characteristics of our culture don’t fit any definition of whiteness. If whiteness doesn’t track to any phenotype at all, the word shouldn’t connect to white skin. Whiteness is nothing but bourgeois culture with a splash of middle class respectability.

The biggest problem with CRT is the conflation of race and culture. White is not a culture because a surfer in Santa Cruz, CA shares nothing in common with an auto technician in Montgomery, Alabama besides skin color and even that is suspect since it’s rare for someone to have actual white skin unless they have albinism. The same applies to brown and Black as well. An Igbo tribal leader and a Detroit graffiti artist share no cultural traits. Neither does a Mayan and an Iranian, both brown people. Race is an essentially meaningless concept that is nothing more than an exercise of pure divisive power to manipulate and control the working class and it works this way no matter what “side” deploys it.

Movements are based on solidarity, not division.

Then, the pandemic hit. Bouncing around in my head had been an idea for a free auto repair shop, but I had had no plans to get back into organizing. When the pandemic hit, I felt like my automotive skills, my leadership qualities, and my friendships were going to be needed to address community needs. So, I got together with old comrades from Birmingham and some new ones from Montgomery and we created The Automotive Free Clinic.

As part of The AFC, we created a study group, again during the pandemic, which had the pretense of reading Marx, but was really about maintaining connections while everyone was isolated. We did this all throughout the pandemic and for about a year afterward. Part of our study was on structures of decentralization, including pirates, organized crime, anarchist theory and movements, and the like. The point of this study was to lay the groundwork for a social movement in the American South of which this paper is a major contributing philosophy. Over the next five years, The AFC would repair upwards of 700 vehicles at cost for community members. It’s an effective community-based, mutual aid institution.

In 2023, The AFC and partner organizations The Habitual Bee, Alabama Center for Rural Organizing and Systemic Solutions (ACROSS), and Sand Mountain Cooperative Education Center (SMCEC) launched the Educational and Economic Resources Organizing Network. In subsequent years, the network has grown to include a number of mutual aid, labor, cooperative, and educational organizations across the American South.

ACROSS - a disaster recovery organization in Camp Hill, Alabama, a 90% Black rural community.

SMCEC - a popular education and cooperative development organization in Guntersville, Alabama, an Appalachian tourist enclave.

Hot Dogs and Harm Reduction - a harm reduction organization in West Virginia

The Habitual Bee - a Black History and urban agricultural organization in Charlotte, NC

The Automotive Free Clinic

Jubilee House - a Christian ministry doing small scale agriculture, a free store, and harm reduction in Parrish, Alabama.

Asheville Garage Goblins - an AFC style shop in Western North Carolina

The Valley Labor Report - a union oriented media organization in Northern Alabama

Conceptually, this network is organized under the principles of pirate anarchism or communism. Each organization is fully autonomous with its own unique structure, philosophy, and organization. There is no centralized authority that dictates to any organization how to do their work. The network exists for cooperation purposes—to share information and resources. Each “pirate ship” can operate on its own volition and can share with other “pirate ships” useful information. Importantly, this type of pirate organization was useful in fighting and surviving colonial powers in the New World.

Pirates and outlaws aren’t really concerned with the government or policy, but if we were, we’d ask for land reform for the working class and reparations for Black and indigenous people. Everybody gets something; Black and indigenous people get more, which is no different from the demands of social movements in the Global South. The South is an internal orient: why not cash in on this trope?

Underpinning all of this is a philosophy of toughness, honesty, resourcefulness, and love, the values rooted in redneck culture. These values and this organizational form are how we survive the coming collapse and it’s not just a theory; it exists in reality.

Conclusion

“I ain’t asking nobody for nothing, I cain’t get it on my own;

You don’t like the way I’m livin’, you can just leave this long haired country boy alone.”

Charlie Daniels

What I want for the South is mostly to be left alone and for us to solve our own problems. Race, gender, addiction, sexuality, poverty, despair, religion, and everything else, we can solve or at least deal with. We don’t need big non-profit, big church, and big corporation going on save-a-ho missions in the American South. We ain’t hoes and we don’t need to be saved.

This goes for the do-gooder crowd, and I’m not totally against y’all as long as you don’t come down here with a bunch of big talk and big plans and just listen for a few years, but big corporation needs to get the fuck out. Y’all ain’t doing shit but extracting wealth from our people. We can already take care of ourselves; we don’t need no fucking “job creation.”

The South ain’t perfect. Our biggest flaw is not racism or homophobia or misogyny or any of the other internally orientalized stories that people tell about us. No, our number one problem is provinciality. It’s not seeing that everything could be remarkably different, that with the exposure to a bit more than what our leaders allow us to see, we could turn the American South into a paradise. We have everything we need—the culture, the practical skills, the history, the philosophy, and the mother fucking grit to do it.

We just need a bit of imagination and to get the Yankees, the ones from the Global North and our own home grown local Yankees, out of our communities.

“…gone, gone with the wind; ain’t nobody looking back again.”

Let's see, a Waylon, David Allen Coe, all 3 Hank Williams, and a Charlie Daniels reference all in one post; sir, I believe you and I could discuss outlaw country music even if I am a born and bred Yankee from Chicago, identify more with rednecks and outlaws then I do with those around me in my community. Hank Williams III has a great voice, his singing style is reminiscent of Willie Nelson's, but as Waylon sings Bob Wills is still the king.

If we were having Thanksgiving dinner I’d get up and clap, credit you with a hell of an oration, skip a few quibbles, and tell you to turn up Hank Sr. - “Settin’ the Woods On Fire” will fit the bill nicely - after you pass the dressing. And FYI, in case you’re wondering: there are a lot of us northerners cut from the same cloth who subscribe to that redneck ethos.