‘That’s cool!’

We’ve probably used the word ‘cool,’ in this sense, a million times in our lives without really knowing what it means.

Our friend Scott Ainslie over at BluesNotes has contributed this piece on the deep Yoruban roots of coolness. Who would have known it’s grounded in a whole metaphysical view of the world that includes SPIRIT POSESSION!

But it’s really about much, much more: it’s also about generating or tapping into an internal moral center of integrity, resistance, and equanimity.

I can’t resist including a song by contemporary bluesman Cedrick Burnside both meditatin’ on and exuding coolness!

-WD James (ed.)

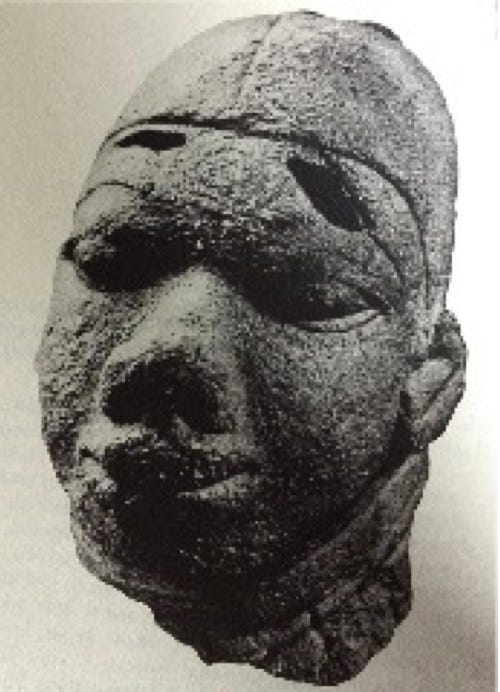

The beautiful, refined terracotta head pictured above was sculpted by an artist in the ancient Yoruba city of Ife-Ife in southwestern Nigeria (around 135 miles northeast of modern-day Lagos) between the 10th and 12th Centuries when, according to Yale Art Historian and author Robert Farris Thompson, “nothing of comparable quality was being produced in Europe.”

Representing a person of status, or an important spirit, this work gives us a face of calm modesty, benevolent dignity and discretion that is perfectly aligned with the spiritual-aesthetic values of the Yoruba culture and artist who created it. Religious and aesthetic values were inseparable for the Yoruba. Beauty requires spirit.

As Thompson notes in Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art and Philosophy:

“The Yoruba assess everything aesthetically – from the taste of a yam to the qualities of a dye, to the dress and deportment of a woman or a man.”

It may startle some to find derivatives of West African aesthetics, ideas, and terminology suffusing contemporary American music and culture, but there are specific, traceable ideas from the Yoruba that remain with us today.

We can learn a great deal about American history, culture, and tradition if we pay attention to Yoruban ideas that crossed the Atlantic, endured the Middle Passage, and penetrated the Caribbean Basin. Especially if we focus not just on what has been saved, but what has been lost.

In the mid-late 1700s, these aesthetic-spiritual traditions migrated to Caribbean and Southern slave ports and were dispersed throughout the country. Their movement was accelerated by the Haitian revolution in the early years of the 19th century.

There are three key components to the aesthetic-spiritual lives of the Yoruba that have influenced Yoruba-based cultures here in the West: Ashe, Iwa, and Itutu.

We'll take them in order, one by one.

Step One–Ashe (Inspiration)

Ashe is characterized by the Yoruba as a morally neutral power. Ashe can give or take away–it can bring life or death, help or harm, according to the purpose and the nature of its bearer. A likely English translation for Ashe is inspiration–to literally have the spirit-power come into you.

Ashe is often associated with the color red and connoted by birds. Additionally, Thompson wrote:

"Ashe is associated with ‘the mothers,’ those most powerful of elderly women with a force capable of mystically annihilating the arrogant, the selfishly rich, or other targets deserving of punishment.”

The Body & The Spirits

In Yoruba-based spiritual cultures scattered throughout the Caribbean and South America, allowing oneself to fall into a ritual trance is one of the formal goals of religious and social ceremonies.

For the ancestors to enter this plane–to help us, warn us, teach us, or protect us; to tell us where what is lost can be found, to foretell the future, or explain the past–the use of a body is required. The spirit needs a human mouth to speak, human eyes to see, human ears to hear.

The ritual surrender of someone's autonomy makes room for the ancestors to come among us.

The body in Yoruba culture, far from being profane, is a kind of lynchpin connecting the sacred world of the spirits with the daily world. The body, with all its desires and messiness, is part and parcel of the spirit world, not antipolar to it.

The body and its natural emotions are neither feared nor shamed but welcomed. There is room for them in Yoruban belief systems.

Possession

When the Spirit comes into someone, they are said to see with god's eyes and hear with the god's ears.

Rather than being trapped by the small, limited perspective of daily concerns, when Ashe comes in, one is literally inspired to a larger vision and provided with a much broader, all-encompassing viewpoint.

In ecstatic ceremonies when a person gives their body up to possession by the ancestors, other members of the community will gather around them to protect them from harm and witness what they say and do.

The possessed worshipper is a well-spring of spirit. People pay attention to what transpires. Thompson quotes Yoruba elders:

“When a person comes under the influence of a spirit, his ordinary eyes swell to accommodate the inner eyes, the eyes of the god. He will then look very broadly across the whole of all the devotees…”

–Flash of the Spirit, p. 9

In this worldview, developing a divinely inspired vision of who we are, what we can accomplish, and how we should carry ourselves in the world is considered a crucial first step in the spiritual and aesthetic development of a well-formed human being.

Step Two–Iwa (Character)

Cultivating a vision rooted in the spirit and the ancestors' long view is a good beginning. But not sufficient. A vision inspired by a larger perspective can present real problems.

Bringing spirit-vision into the community where it can be useful to all, requires significant discipline, force of will, and personal power–things that in English we loosely summarize as ‘character.’

Like Ashe, Iwa (good character and a spotless reputation) originates in the sacred.

When the Yoruba recognize an inspired vision (Ashe) active in combination with power to make things happen (Iwa) in a person, a work of art, natural beauty, social relations, or other forces at work in the world, they name it: Itutu.

Itutu can be used to describe beautiful sculpture, an inspired section of drumming or dancing, an act of generosity or kindness under duress, or even simple daily courtesy. Grace–in its most mundane and expansive sense–is another word that could also apply. A certain generosity and calmness of spirit is in play.

And Itutu translates as cool.

Step Three–Itutu (Coolness)

If one successfully cultivates an inspired vision of the world (Ashe) and demonstrates the will and strength of character (Iwa) to bring that vision into being, then we see that that person's actions, their visage, their comportment, their inner and outward behavior express a certain immutable nobility.

They carry themselves with dignity and modesty. They are honest and neither excessively humble nor proud. Holding to their inspired vision, their god’s eye view, they are untroubled by irritations, large and small.

When these remarkable external qualities are observed by the community at large, they are recognized as Itutu.

Recognizing Inspired Beauty & Goodness

We could all name signature leaders throughout history who have operated out of an inspired vision of how the world around them–and they, themselves–could be. Leaders who have given of themselves and sacrificed for the common good and have set exemplary standards of service to the community.

We might quibble over the list, but Mohandas K. Gandhi, Mother Theresa, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, and Dr. Martin Luther King readily come to mind. Also Malcolm X and Steven Biko. There are many others.

Famous or not, for the Yoruba, the experience of divine inspiration, the powerful development of personal character, and the achievement of Itutu remain open to us all. Not limited by gender, race, class, or religion, they are earned. They are self-evident: the evidence is in the self.

We continue to live in either the light or the shadow of these Yoruban aesthetic-spiritual values. We hear remnants of them all the time: cool, chill out.

In the terra cotta head pictured above, the inner assurance of Ashe/Inspired is portrayed by the outer signs of Iwa (surety, calmness, quiet strength, and the color red).

Neither overly smiling nor sad, the figure's peaceful countenance, the sealed lips signaling personally held counsel, and the calm, quiet, wide eyes communicate the spiritual-aesthetic accomplishments of the person or spirit portrayed. An island of calm in a chaotic world, this person was–and this work of art is–Itutu/Cool.

Beauty and Coolness

According to Yoruba elders, beauty is a part of coolness (Itutu). But of beauty and character, character is greater.

Beauty is not forever–the young become old, the flower fades; artfully made material objects wear out, break, or are stolen.

But Iwa-character retains its power–a force that can be refined throughout one’s life. Character burns brighter. Character does not fade. Character cannot be taken. It can only be destroyed from within.

“Coolness, then, is a part of character, and character objectifies proper custom.

"To the degree that we live generously and discreetly, exhibiting grace under pressure, our appearance and our actions gradually assume virtual royal power. As we become noble, fully realizing the spark of creative goodness God endowed us with…we find the confidence to cope with all kinds of situations.

"This is Ashe. This is character. This is mystic coolness. All one. Paradise is regained, for Yoruba art returns the idea of heaven to mankind wherever the ancient ideal attitudes are genuinely manifested.”

–Flash of the Spirit, p. 16

As a Yourba man myself, this information is very insightful! Thanks for taking the time to dive into this and for sharing! Will definitely be resharing across multiple platforms!