Hey Folks,

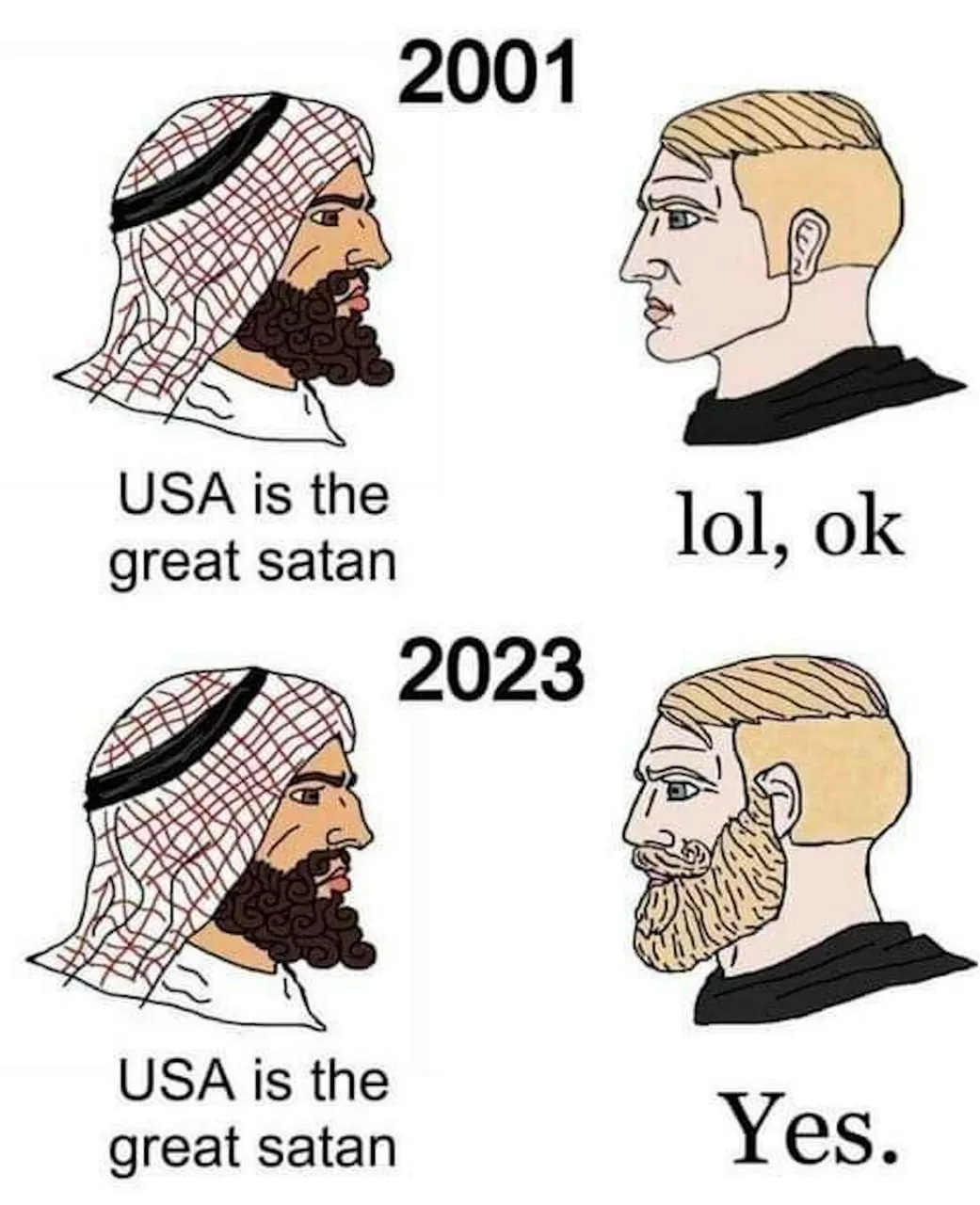

Well, it’s been 23 years since the Empire declared War on itself. This may be a small comfort, but I definitely don’t think The Project for a New American Century is going according to plan.

What I have for you this September 11th is a very interesting piece of information about the Twin Towers that has been overlooked by just about every single 9/11 Truther ever. I’ve never even heard James Corbett mention it, although I wouldn’t be surprised if someone pops up to say “Well, actually…”

Today’s post comes to you courtesy of the late, great David Graeber, who died mysteriously in 2020 and is presumed to have been poisoned by his wife, Nika Dubrovsky.

It is the twelve chapter of his magnum opus, Debt: The First Five Thousand Years, which I consider the greatest work of political economy ever written by an anarchist.

It contains information about the Twin Towers that I don’t recall hearing anywhere else; namely, that they sat atop an underground complex, built on the bedrock of Manhattan Island, where the gold reserves of the Federal Reserve were warehoused.

“Wait a minute,” I hear you asking. “What about Fort Knox?”

Well, according to David Graeber:

While the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves are indeed kept at Fort Knox, the Federal Reserve’s gold reserves, along with those of more than 100 other central banks, governments, and organizations, are stored in vaults under the Federal Reserve building at 33 Liberty Street in Manhattan, just two blocks away from the Towers. At roughly 5,000 metric tons (266 million troy ounces), these combined reserves represent, according to the Fed’s own website, somewhere between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the gold ever mined from the earth.

Dang. How did I not know that?

Anyway, there’s no reason to believe that this gold was destroyed by the attacks, but it does go to show the World Trade Centres really were the financial epicentre of the global capitalist system.

Given the rapaciousness of that system, I think that we should acknowledge that the Twin Towers were valid targets for those wishing to strike against the Empire that was responsible for so many wars, coups, plunder, debt-peonage schemes, war crimes, debt-monetization scams, and much miscellaneous fuckery.

I think we should mourn the people who died that day, but we should also recognize that the Twin Towers were a valid military target.

I, like most of you, assume that 9/11 was an inside job, and that it was carried out by members of the C.I.A. and Mossad.

If you’re in any doubt as to whether 9/11 was an inside job or not, or if you know someone who is, I suggest checking out this amazing interview in which FBI counterterrorism czar Richard Clark straight up accuses the C.I.A. of orchestrating and carrying out the attack.

This video really must be seen to be believed.

That said, we can assume that the C.I.A. agents who carried out this attacks were working on behalf of someone. This has always been assumed to be neocons like the Bush family, arms companies, oil companies, and Pentagon war hawks who wanted to secure their dominant position by controlling the world’s oil supply. But if you understand how common it is in the world of intelligence for spooks to be double or triple agents, I think it’s not as far-fetched as you might think to ask if they could have been serving more than one master.

When we look back on 9/11 after 23 years and retrospectively ask the question “Cui Bono?” (Who benefits?), the answer looks a little different now than it did in, say, 2003.

Maybe this is just the way cookie crumbled. Maybe the U.S. simply miscalculated and overplayed their hand. Maybe the CCP just keeps getting lucky. But I can’t help but notice that everything since 2001 keeps coming up China.

I’ll take this moment to remind you that the oft-repeated phrase “All Warfare is Based On Deception” comes from The Art of War.

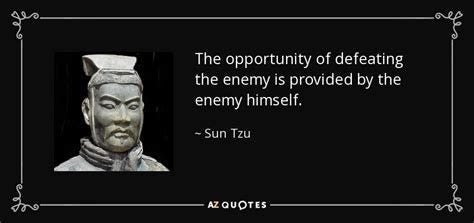

Sun Tzu also said a lot of other things that seem eerily relevant in the light of recent history.

Take this one, for example: “the opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself”.

It is clear to me by now that China has been using the rapacious greed of Wall Street against itself. It’s incredibly brilliant, if you ask me. You can’t tell me that isn’t poetic justice.

Chinese military strategy also appears to be using the King Kong chest-pounding bravado of the U.S. military against itself, which again, is straight out of The Art of War.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, I suggest watching the following video, in which General Wesley Clark describes the insanity at the Pentagon in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, when the U.S. high command drew up plans to “take out seven country in five years”, to use his words.

Fast forward twenty-three years, and the U.S. Empire is so over-extended that its complete collapse seems inevitable.

I don’t know about you, but I’m starting to think that WWIII might have actually started way back on September 11th, 2001.

And I suspect that those agents who pulled off those attacks were playing into the hands of the CCP, whether they knew it or not.

And it’s pretty obvious who’s winning WWIII, isn’t it?

One thing is for sure - that a financial war has been raging for years. If you want to understand how the pieces fit together, you absolutely must read Debt: The First Five Thousand Years.

You could also get out my David Graeber primer Mafia Capitalism 101.

I also suggest reading The Art of War, Quotations from Chairman Mao, and Sam Cooper’s Wilful Blindness.

Read those three books, and everything will click into place.

You might also want to watch that famous interview where KGB agent Yuri Bezmenov warns Americans of the extent to which their country has been infiltrated by foreign agents.

They won, folks. It’s as simple as that. And no, this has nothing to do with communism versus capitalism. This is about power, pure and simple. The CCP abandoned Marxism ages ago.

The West has been played like a violin, and it’s time to get used to the idea that China truly is top dog now.

Still don’t believe me?

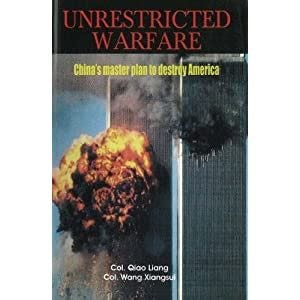

Check out the cover of this book, which was published in 1999:

I rest my case.

Yeah, yeah, it kinda sucks that a terrifyingly authoritarian regime now rules the world… but what else is new?

I prefer to look at the bright side: Palestine will soon be Free!

Solidarity Forever,

Crow Qu’appelle

P.S. Here’s the audiobook version of Unrestricted Warfare:

It can also be found on the Internet Archive here.

THE BEGINNING OF SOMETHING YET TO BE DETERMINED

(1971 – PRESENT)

Look at all these bums: If only there were a way of finding out how much they owe. —

Repo Man (1984)

Free your mind of the idea of deserving, of the idea of earning, and you will begin to be able to think.

—Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed

On August 15, 1971, United States President Richard Nixon announced that foreign-held U.S. dollars would no longer be convertible into gold, thus stripping away the last vestige of the international gold standard. This marked the end of a policy effective since 1931, and confirmed by the Bretton Woods accords at the end of World War II, which stated that while U.S. citizens could no longer cash in their dollars for gold, U.S. currency held outside the country was redeemable at the rate of $35 an ounce. By doing so, Nixon initiated the regime of free-floating currencies that continues to this day.

The consensus among historians is that Nixon had little choice. His hand was forced by the rising costs of the Vietnam War, a conflict that, like all capitalist wars, had been financed by deficit spending. The United States possessed a large proportion of the world’s gold reserves in Fort Knox (though increasingly less in the late 1960s, as other governments, most famously Charles de Gaulle’s France, began demanding gold for their dollars). Most poorer countries, in contrast, kept their reserves in dollars. The immediate effect of Nixon’s unpegging of the dollar was to cause the price of gold to skyrocket, reaching a peak of $600 an ounce by 1980. This caused U.S. gold reserves to increase dramatically in value, while the value of the dollar, as denominated in gold, plummeted. The result was a massive net transfer of wealth from poor countries, which lacked gold reserves, to rich ones, like the United States and Great Britain, that maintained them. In the U.S., it also triggered persistent inflation.

Whatever Nixon’s reasons, once the global system of credit money was entirely unpegged from gold, the world entered a new phase of financial history—one that nobody fully understands. While I was growing up in New York, I would hear rumors of secret gold vaults underneath the Twin Towers in Manhattan. Supposedly, these vaults contained not just U.S. gold reserves but also those of all the major economic powers. The gold was kept in bars, piled up in separate vaults, one for each country. Every year, when the balance of accounts was calculated, workmen with dollies would adjust the stocks, carting, say, a few million in gold from the vault marked “Brazil” and transferring them to the one marked “Germany,” and so on.

Apparently, many people had heard these stories. After the Towers were destroyed on September 11, 2001, one of the first questions many New Yorkers asked was: What happened to the money? Was it safe? Were the vaults destroyed? Some believed the gold had melted. Was this the attackers' real aim? Conspiracy theories abounded. Some spoke of emergency workers secretly summoned to cart off tons of bullion from overheated tunnels even as rescue workers labored above. One particularly colorful conspiracy theory suggested the entire attack was staged by speculators expecting the value of the dollar to crash and gold to skyrocket—either because the reserves had been destroyed or because they had planned to steal them.

The remarkable thing is that, after believing this story for years and then being convinced by knowledgeable friends that it was all a myth (one friend said, “The U.S. keeps its gold reserves in Fort Knox”), I did some research and found out that it’s partly true. While the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves are indeed kept at Fort Knox, the Federal Reserve’s gold reserves, along with those of more than 100 other central banks, governments, and organizations, are stored in vaults under the Federal Reserve building at 33 Liberty Street in Manhattan, just two blocks away from the Towers. At roughly 5,000 metric tons (266 million troy ounces), these combined reserves represent, according to the Fed’s own website, somewhere between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the gold ever mined from the earth. Children are even taken on tours of it.

The gold stored at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York,” according to the promotional literature, “is secured in a most unusual vault. It rests on the bedrock of Manhattan Island—one of the few foundations considered adequate to support the weight of the vault, its door, and the gold inside—eighty feet below street level and fifty feet below sea level... To reach the vault, bullion-laden pallets must be loaded into one of the Bank’s elevators and sent down five floors below street level to the vault floor... If everything is in order, the gold is either moved to one or more of the vault’s 122 compartments assigned to depositing countries and official international organizations or placed on shelves. ‘Gold stackers,’ using hydraulic lifts, do indeed shift them back and forth between compartments to balance credits and debts, though the vaults have only numbers, so even the workers don’t know who is paying whom.”

There is no reason to believe, however, that these vaults were in any way affected by the events of September 11, 2001.

Reality, then, has become so odd that it’s hard to guess which elements of grand mythic fantasies are really fantasy, and which are true. The image of collapsed vaults, melted bullion, and secret workers scurrying deep below Manhattan with underground forklifts evacuating the world economy—all this turns out not to be true. But is it entirely surprising that people were willing to consider it?

What I would like to do in this chapter is, primarily, not so much to provide a detailed analysis of how the current system works, but to look at how the long-term patterns I’ve been examining so far can be seen as playing out at the present moment, and might provide us at least a hint of where it might be heading. Because this is definitely a moment of transition. No one is going to be able to say what all this really means for another generation, at the very least. On the other hand, as an anthropologist, I cannot help but see this confused play of symbols as important in and of itself, even playing a crucial role in maintaining the forms of power it claims to represent. In part, these systems work because no one knows how they really work.

In America, the banking system since the days of Thomas Jefferson has shown a remarkable capacity to inspire paranoid fantasies: whether centering on Freemasons, Elders of Zion, the Secret Order of the Illuminati, or the Queen of England’s drug-money-laundering operations, or any of a thousand other secret conspiracies and cabals. It’s the main reason why it took so long for an American central bank to be established to begin with. In a way, there’s nothing surprising here. The United States has always been dominated by a certain market populism, and the ability of banks to “create money out of nothing”—and even more, to prevent anyone else from doing so—has always been the bugaboo of market populists, since it directly contradicts the idea that markets are a simple expression of democratic equality. Still, since Nixon’s floating of the dollar, it has become evident that it’s only the wizard behind the screen who seems to be maintaining the viability of the whole arrangement. Under the free-market orthodoxy that followed, we have all been asked, effectively, to accept that “the market” is a self-regulating system, with the rising and falling of prices akin to a force of nature, and simultaneously to ignore the fact that, in the business pages, it is simply assumed that markets rise and fall mainly in anticipation of, or reaction to, decisions by Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke, or whoever is currently the chairman of the Federal Reserve.

One element, however, tends to go flagrantly missing in even the most vivid conspiracy theories about the banking system, let alone in official accounts: the role of war and military power. There’s a reason why the wizard has such a strange capacity to create money out of nothing. Behind him, there’s a man with a gun.

True, in one sense, he’s been there from the start. I have already pointed out that modern money is based on government debt, and that governments borrow money in order to finance wars. This is just as true today as it was in the age of King Philip II. The creation of central banks represented a permanent institutionalization of that marriage between the interests of warriors and financiers that had already begun to emerge in Renaissance Italy and eventually became the foundation of financial capitalism.

Nixon floated the dollar to pay for the cost of a war in which, during the period of 1970–1972 alone, he ordered more than four million tons of explosives and incendiaries to be dropped on cities and villages across Indochina—causing one senator to dub him “the greatest bomber of all time.” The debt crisis was a direct result of the need to pay for the bombs, or more precisely, the vast military infrastructure required to deliver them. This was what was causing such an enormous strain on the U.S. gold reserves. Many hold that by floating the dollar, Nixon converted the U.S. currency into pure “fiat money”—mere pieces of paper, intrinsically worthless, that were treated as money only because the U.S. government insisted that they should be. In that case, one could argue that U.S. military power was now the only thing backing up the currency. In a certain sense, this is true, but the notion of “fiat money” assumes that money really “was” gold in the first place. In reality, we are dealing with another variation of credit money.

Contrary to popular belief, the U.S. government can’t “just print money,” because American money is not issued by the Federal government at all, but by private banks under the aegis of the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve, in turn, is a peculiar sort of public-private hybrid—a consortium of privately owned banks whose Governing Board is appointed by the U.S. president with Congressional approval, but which otherwise operates autonomously. All dollar bills in circulation in America are “Federal Reserve Notes”—the Fed issues them as promissory notes and commissions the U.S. mint to do the actual printing, paying it four cents for each bill. The arrangement is just a variation of the scheme originally pioneered by the Bank of England, whereby the Fed “loans” money to the U.S. government by purchasing Treasury bonds and then monetizes the U.S. debt by lending the money thus owed by the government to other banks. The difference is that while the Bank of England originally loaned the king gold, the Fed simply whisks the money into existence by saying that it’s there. Thus, it’s the Fed that has the power to print money. The banks that receive loans from the Fed are no longer permitted to print money themselves, but they are allowed to create virtual money by making loans, ostensibly at a fractional reserve rate established by the Fed—though in practice, even these restrictions have become largely theoretical.

All this is a bit of a simplification: monetary policy is endlessly arcane and, it sometimes seems, intentionally so. (Henry Ford once remarked that if ordinary Americans ever found out how the banking system really worked, there would be a revolution tomorrow.) There is no end to the smoke and mirrors here. For instance, while technically, the Fed cannot lend money directly to the government by buying Treasury Bonds, everyone knows that doing so indirectly is one of its primary reasons for being. And insofar as the government issues T-bonds, it is actually, in one sense, printing money: circulating debt tokens that—as one apparently paradoxical effect of Nixon’s floating the dollar—have now themselves come to replace gold as the world’s reserve currency: that is, as the ultimate store of value in the world, yielding the United States enormous economic advantages.

Meanwhile, the U.S. debt remains, as it has been since 1790, a war debt: the United States continues to spend more on its military than do all other nations on earth combined, and military expenditures are not only the basis of the government’s industrial policy; they also take up such a huge proportion of the budget that by many estimations, were it not for them, the United States would not run a deficit at all.

The U.S. military, unlike any other, maintains a doctrine of global power projection: that it should have the ability, through roughly 800 overseas military bases, to intervene with deadly force anywhere on the planet. In a way, land forces are secondary; since World War II, the key to U.S. military doctrine has always been a reliance on air power. The United States has fought no war in which it did not control the skies, and it has relied on aerial bombardment far more systematically than any other military. In its recent occupation of Iraq, for instance, it even went so far as to bomb residential neighborhoods of cities ostensibly under its own control. The essence of U.S. military predominance in the world is ultimately the fact that it can, at will, with only a few hours' notice, drop bombs anywhere on the surface of the planet. No other government has ever had anything remotely like this capability. A case could be made that this cosmic power holds the entire world monetary system, organized around the dollar, together.

Again, we are talking about symbolic power. It’s a form of power that works largely insofar as it remains symbolic. During the Cold War, the United States and USSR were considered superpowers because their leaders had the means, through their nuclear arsenals, to destroy humanity with the flick of a switch. Obviously, this power could only be translated into political influence insofar as it wasn’t actually exercised. In a more subtle way, this is still true of U.S. cosmic pretensions. They don't work by direct threat but by creating a political environment defined by knowledge of utterly disproportionate access to violence. That sense of absolute power tends to erode the moment violence is used more than sparingly, and largely in symbolic ways.

How Does It Work Economically?

Because of the United States’ trade deficits, huge numbers of dollars circulate outside the country. One effect of Nixon’s floating of the dollar was that foreign central banks have little they can do with these dollars except to use them to buy U.S. Treasury bonds. This is what is meant by the dollar becoming the world’s “reserve currency.” These bonds, like all bonds, are supposed to be loans that will eventually mature and be repaid, but as economist Michael Hudson, who first began observing the phenomenon in the early ’70s, noted, they never really do:

“To the extent that these Treasury IOUs are being built into the world’s monetary base, they will not have to be repaid but are to be rolled over indefinitely. This feature is the essence of America’s free financial ride, a tax imposed at the entire globe’s expense.”

What’s more, Hudson notes, over time, the combined effect of low-interest payments and inflation is that these bonds actually depreciate in value, adding to the tax effect, or as I preferred to put it in the first chapter, “tribute.” Economists prefer to call it “seigniorage.” The effect, though, is that American imperial power is based on a debt that will never—can never—be repaid. Its national debt has become a promise, not just to its own people but to the nations of the entire world, that everyone knows will not be kept.

At the same time, U.S. policy insists that those countries relying on U.S. Treasury bonds as their reserve currency behave in exactly the opposite way: observing tight money policies and scrupulously repaying their debts.

As I’ve already observed, since Nixon’s time, the most significant overseas buyers of U.S. Treasury bonds have tended to be banks in countries that were effectively under U.S. military occupation. In Europe, Nixon’s most enthusiastic ally in this respect was West Germany, which then hosted more than three hundred thousand U.S. troops. In more recent decades, the focus has shifted to Asia, particularly the central banks of countries like Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea—again, all U.S. military protectorates. In addition, the global status of the dollar is reinforced by the fact that, since 1971, it is the only currency used to buy and sell petroleum, with any attempt by OPEC countries to begin trading in any other currency stubbornly resisted by OPEC members Saudi Arabia and Kuwait—also U.S. military protectorates. When Saddam Hussein made the bold move of switching from the dollar to the euro in 2000, followed by Iran in 2001, this was quickly followed by American bombing and military occupation.

How much did Hussein’s decision to buck the dollar weigh into the U.S. decision to depose him? It’s impossible to say. His decision to stop using “the enemy’s currency,” as he put it, was one in a series of hostile gestures that likely would have led to war in any event. What’s important is that there were widespread rumors that this was one of the major contributing factors, and therefore, no policymaker in a position to make a similar switch can completely ignore the possibility. Much though their beneficiaries do not like to admit it, all imperial arrangements ultimately rest on terror.

The immediate effects of the advent of the free-floating dollar marked not a break with the alliance of warriors and financiers on which capitalism itself was originally founded, but something that looks like its ultimate apotheosis. Neither has the return to virtual money led to a great return to relations of honor and trust. Quite the contrary. However, we are talking about the very first years of what is likely to be a centuries-long historical era. By 1971, most of these changes had not even begun. The American Express card, the first general-purpose credit card, had been invented only thirteen years before, and the modern national credit card system had only really come into being with the advent of Visa and MasterCard in 1968. Debit cards came later, creatures of the 1970s, and the current, largely cashless economy only came into being in the 1990s. All of these new credit arrangements were mediated not by interpersonal relations of trust but by profit-seeking corporations, and one of the earliest and greatest political victories of the U.S. credit card industry was the elimination of all legal restrictions on what they could charge as interest.

If history holds true, an age of virtual money should mean a movement away from war, empire-building, slavery, and debt peonage (waged or otherwise), and toward the creation of some sort of overarching institutions, global in scale, to protect debtors. What we have seen so far is the opposite. The new global currency is rooted in military power even more firmly than the old was. Debt peonage continues to be the main principle of recruiting labor globally: either in the literal sense, in much of East Asia or Latin America, or in the subjective sense, whereby most of those working for wages or even salaries feel that they are doing so primarily to pay off interest-bearing loans. The new transportation and communications technologies have just made it easier, making it possible to charge domestic workers or factory laborers thousands of dollars in transportation fees, and then have them work off the debt in distant countries where they lack legal protections.

Insofar as overarching cosmic institutions have been created that might be considered in any way parallel to the divine kings of the ancient Middle East or the religious authorities of the Middle Ages, they have not been created to protect debtors but to enforce the rights of creditors. The International Monetary Fund is only the most dramatic case in point here. It stands at the pinnacle of a great, emerging global bureaucracy—the first genuinely global administrative system in human history, consisting not only of the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization, but also of the endless host of economic unions, trade organizations, and non-governmental organizations that work in tandem with them—created largely under U.S. patronage. All of them operate on the principle that “one has to pay one’s debts”—unless one is the U.S. Treasury or perhaps American Insurance Group—since the specter of default by any country is assumed to imperil the entire world monetary system.

All true. But again, we are speaking of a mere forty years here, in what is likely to be a 400- or 500-year epoch. Nixon’s gambit, what Hudson calls “debt imperialism,” has already come under considerable strain. The first casualty was precisely the imperial bureaucracy dedicated to the protection of creditors (other than those owed money by the United States). IMF policies of insisting that debts be repaid almost exclusively from the pockets of the poor were met by an equally global movement of social rebellion (the so-called “anti-globalization movement”—though the name is profoundly deceptive), followed by outright fiscal rebellion in both East Asia and Latin America. By 2000, East Asian countries had begun a systematic boycott of the IMF. In 2002, Argentina committed the ultimate sin: they defaulted—and got away with it.

Subsequent U.S. military adventures were clearly meant to reestablish the nation’s symbolic, cosmological power—that is, to terrify and overawe—but in that respect, they do not appear to have been very successful. Partly because they demonstrated that the U.S. military was unable to totally overcome far weaker rivals, and partly because, to finance them, the United States had to turn not just to its military clients, but increasingly to China, its chief remaining military rival. After the near-total collapse of the U.S. financial industry, which despite having been very nearly granted rights to create money at will, still managed to accumulate trillions in liabilities it could not pay, the U.S. lost even the ability to argue that debt imperialism guaranteed stability.

To illustrate the severity of the financial crisis, here are some statistical charts culled from the pages of the St. Louis Federal Reserve web page.

Here is the amount of U.S. debt held overseas:

Meanwhile, private U.S. banks reacted to the crash by abandoning any pretense that we are dealing with a market economy, shifting all available assets into the coffers of the Federal Reserve itself:

Allowing them, through yet another piece of arcane magic that none of us could possibly understand, to end up, after an initial near $400-billion dip, with far larger reserves in their own balance sheets than they had ever had before.

At this point, some U.S. creditors clearly feel they are finally in a position to demand that their own political agendas be taken into account.

CHINA WARNS U.S. ABOUT DEBT MONETIZATION

Seemingly everywhere he went on a recent tour of China, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher was asked to deliver a message to Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke: “stop creating credit out of thin air to purchase U.S. Treasuries.”

On August 15, 1971, United States President Richard Nixon announced that foreign-held U.S. dollars would no longer be convertible into gold—stripping away the last vestige of the international gold standard. This marked the end of a policy that had been effective since 1931, and confirmed by the Bretton Woods accords at the end of World War II: while United States citizens were no longer allowed to cash in their dollars for gold, all U.S. currency held outside the country was redeemable at the rate of $35 an ounce. By doing so, Nixon initiated the regime of free-floating currencies that continues to this day.

The consensus among historians is that Nixon had little choice. His hand was forced by the rising costs of the Vietnam War—like many capitalist wars, financed by deficit spending. The United States was in possession of a large proportion of the world’s gold reserves, stored in Fort Knox (though these reserves were decreasing by the late 1960s, as other governments, most famously France under Charles de Gaulle, began demanding gold for their dollars). Most poorer countries, by contrast, kept their reserves in dollars. The immediate effect of Nixon’s action was to cause the price of gold to skyrocket, hitting a peak of $600 an ounce by 1980. This caused U.S. gold reserves to increase dramatically in value, while the value of the dollar, as denominated in gold, plummeted. The result was a massive net transfer of wealth from poor countries, which lacked gold reserves, to rich ones, like the United States and Great Britain. In the U.S., it also triggered persistent inflation.

Whatever Nixon’s reasons, the unpegging of the dollar from gold ushered in a new phase of financial history—one that nobody fully understands. Growing up in New York, I would hear rumors of secret gold vaults beneath the Twin Towers in Manhattan. Supposedly, these vaults contained not only U.S. gold reserves but also those of major economic powers. The gold, stored in bars, was said to be kept in separate vaults for each country, and each year, as accounts were settled, workmen would adjust the stocks accordingly, moving gold between countries as necessary.

After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, one of the first questions many New Yorkers asked was: What happened to the money? Was it safe? Were the vaults destroyed? Many wondered if the gold had melted or if emergency workers had been called in to cart off the bullion as rescue efforts took place above. One particularly colorful conspiracy theory claimed that the entire attack was staged by speculators who, like Nixon, expected the value of the dollar to crash and that of gold to skyrocket—whether because the reserves were destroyed or because they had planned to steal them beforehand.

What is remarkable about these stories is that, after initially dismissing them, I later discovered that they were partly true. While the United States' gold reserves are kept at Fort Knox, the Federal Reserve’s gold reserves, along with those of more than one hundred other central banks and organizations, are indeed stored in vaults beneath the Federal Reserve building at 33 Liberty Street, two blocks from the Towers. Together, these reserves represent somewhere between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the gold ever mined from the earth.

According to promotional literature from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York:

“The gold stored at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is secured in a most unusual vault. It rests on the bedrock of Manhattan Island—one of the few foundations considered adequate to support the weight of the vault, its door, and the gold inside—eighty feet below street level and fifty feet below sea level...”

Bullion is loaded into one of the Bank’s elevators and sent down five floors to the vault floor. If everything is in order, the gold is moved to one of 122 compartments assigned to various countries and international organizations, or placed on shelves. Gold stackers use hydraulic lifts to shift the bullion between compartments as credits and debts are settled, though the vaults themselves are numbered, so even the workers don’t know which countries are involved in each transfer.

There is no reason to believe these vaults were affected by the events of September 11, 2001.

Again, it’s never clear whether the money siphoned from Asia to support the U.S. war machine is better seen as "loans" or as "tribute." Still, the sudden advent of China as a major holder of U.S. treasury bonds has clearly altered the dynamic. Some might question why, if these really are tribute payments, the United States’ major rival would be buying treasury bonds in the first place—let alone agreeing to various tacit monetary arrangements to maintain the value of the dollar, and hence, the buying power of American consumers. But I think this is a perfect case in point of why taking a long-term historical perspective can be so helpful.

From a longer-term perspective, China’s behavior isn’t puzzling at all. In fact, it’s quite true to form. The unique thing about the Chinese empire is that it has, since the Han dynasty at least, adopted a peculiar sort of tribute system whereby, in exchange for recognition of the Chinese emperor as world-sovereign, they have been willing to shower their client states with gifts far greater than they receive in return. This technique seems to have been developed almost as a kind of trick when dealing with the “northern barbarians” of the steppes, who always threatened Chinese frontiers: a way to overwhelm them with such luxuries that they would become complacent, effeminate, and unwarlike. It was systematized in the “tribute trade” practiced with client states like Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and various Southeast Asian states. For a brief period from 1405 to 1433, it even extended to a world scale under the famous eunuch admiral Zheng He. He led a series of seven expeditions across the Indian Ocean, his great “treasure fleet”—in dramatic contrast to the Spanish treasure fleets a century later—carrying not only thousands of armed marines but endless quantities of silks, porcelain, and other Chinese luxuries to present to local rulers willing to recognize the authority of the emperor.

All this was ostensibly rooted in an ideology of extraordinary chauvinism (“What could these barbarians possibly have that we really need, anyway?”), but applied to China’s neighbors, it proved to be extremely wise policy for a wealthy empire surrounded by smaller but potentially troublesome kingdoms. In fact, it was such wise policy that the U.S. government, during the Cold War, more or less had to adopt it, creating remarkably favorable terms of trade for those very states—Korea, Japan, Taiwan, certain favored allies in Southeast Asia—that had been traditional Chinese tributaries, in this case to contain China.

Bearing all this in mind, the current picture begins to fall into place. When the United States was far and away the predominant world economic power, it could afford to maintain Chinese-style tributaries. Thus, these very states, alone among U.S. military protectorates, were allowed to catapult themselves out of poverty and into first-world status. After 1971, as U.S. economic strength relative to the rest of the world began to decline, these countries were gradually transformed back into a more old-fashioned sort of tributary. Yet China’s entry into this dynamic introduced an entirely new element. There is every reason to believe that, from China’s point of view, this is the first stage of a very long process of reducing the United States to something like a traditional Chinese client state. And, of course, Chinese rulers, like the rulers of any empire, are not primarily motivated by benevolence. There is always a political cost, and what we are beginning to see now are the first glimmers of what that cost might ultimately be.

All of this serves to underline a reality that has come up constantly throughout this book: money has no essence. It’s not “really” anything; therefore, its nature has always been and presumably always will be a matter of political contention. This was certainly true throughout earlier stages of U.S. history, as the endless nineteenth-century battles between goldbugs, greenbackers, free bankers, bimetallists, and silverites so vividly attest. Or consider the fact that American voters were so suspicious of the idea of central banks that the Federal Reserve system was only created on the eve of World War I, three centuries after the Bank of England. Even the monetization of the national debt is, as I’ve already noted, double-edged. It can be seen—as Jefferson saw it—as the ultimate pernicious alliance of warriors and financiers; but it also opened the way to viewing government itself as a moral debtor, and freedom as something literally owed to the nation. Perhaps no one put it more eloquently than Martin Luther King Jr. in his “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963:

“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

One can see the great crash of 2008 in the same light—as the outcome of years of political tussles between creditors and debtors, rich and poor. True, on a certain level, it was exactly what it seemed to be: a scam, an incredibly sophisticated Ponzi scheme designed to collapse with the full knowledge that the perpetrators would be able to force the victims to bail them out. On another level, it could be seen as the culmination of a battle over the very definition of money and credit.

By the end of World War II, the specter of an imminent working-class uprising that had haunted the ruling classes of Europe and North America for the previous century had largely disappeared. This was because class war was suspended by a tacit settlement. To put it crudely: the white working class of the North Atlantic countries, from the United States to West Germany, were offered a deal. If they agreed to set aside any fantasies of fundamentally changing the nature of the system, they would be allowed to keep their unions, enjoy a wide variety of social benefits (pensions, vacations, health care …), and, perhaps most importantly, know that their children had a reasonable chance of leaving the working class entirely, through generously funded and ever-expanding public educational institutions. One key element in all this was a tacit guarantee that increases in workers’ productivity would be met by increases in wages—a guarantee that held good until the late 1970s. Largely as a result, the period saw both rapidly rising productivity and rapidly rising incomes, laying the basis for the consumer economy of today.

Economists call this the “Keynesian era,” since it was a time in which John Maynard Keynes’ economic theories, which already formed the basis of Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States, were adopted by industrial democracies worldwide. With them came Keynes’ rather casual attitude toward money. The reader will recall that Keynes fully accepted that banks do, indeed, create money “out of thin air,” and that for this reason, there was no intrinsic reason that government policy should not encourage this during economic downturns as a way of stimulating demand—a position that had long been dear to the heart of debtors and anathema to creditors.

Keynes himself had in his day been known to make some fairly radical noises, for instance calling for the complete elimination of that class of people who lived off other people’s debts—the “euthanasia of the rentier,” as he put it—though all he really meant by this was their elimination through a gradual reduction of interest rates. As in so much of Keynesianism, this was much less radical than it first appeared. Actually, it was quite squarely in the great tradition of political economy, hearkening back to Adam Smith’s ideal of a debtless utopia and especially David Ricardo’s condemnation of landlords as parasites, their very existence inimical to economic growth. Keynes was simply proceeding along the same lines, seeing rentiers as a feudal holdover inconsistent with the true spirit of capital accumulation. Far from advocating revolution, he saw it as the best way of avoiding one:

I see, therefore, the rentier aspect of capitalism as a transitional phase which will disappear when it has done its work. And with the disappearance of its rentier aspect much else in it besides will suffer a sea-change. It will be, moreover, a great advantage of the order of events which I am advocating, that the euthanasia of the rentier, of the functionless investor, will be nothing sudden … and will need no revolution.

When the Keynesian settlement was finally put into effect after World War II, it was offered only to a relatively small slice of the world’s population. As time went on, more and more people wanted in on the deal. Almost all of the popular movements from 1945 to 1975, even perhaps revolutionary movements, could be seen as demands for inclusion: demands for political equality that assumed equality was meaningless without some level of economic security. This was true not only of movements by minority groups in North Atlantic countries who had first been left out of the deal—such as those for whom Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke—but also of what were then called “national liberation” movements from Algeria to Chile, which represented certain class fragments in what we now call the Global South. Finally, and perhaps most dramatically, there were the feminist movements of the late 1960s and 1970s.

At some point in the 1970s, things reached a breaking point. It would appear that capitalism, as a system, simply cannot extend such a deal to everyone. Quite possibly, it wouldn’t even remain viable if all its workers were free wage laborers. Certainly, it will never be able to provide everyone in the world the sort of life enjoyed by, say, a 1960s auto worker in Michigan or Turin with his own house, garage, and children in college—and this was true even before so many of those children began demanding less stultifying lives. The result might be termed a “crisis of inclusion.” By the late 1970s, the existing order was clearly in a state of collapse, plagued simultaneously by financial chaos, food riots, oil shocks, widespread doomsday prophecies of the end of growth, and ecological crises—all of which, it turned out, served as ways to put the populace on notice that all deals were off.

Once we start framing the story this way, it’s easy to see that the next thirty years, from roughly 1978 to 2009, followed nearly the same pattern. The deal had changed, though. When both Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the UK launched systematic attacks on the power of labor unions and on the legacy of Keynes, they were explicitly declaring that all previous deals were off. Everyone could now have political rights—even, by the 1990s, most people in Latin America and Africa—but political rights would become economically meaningless. The link between productivity and wages was severed: productivity rates have continued to rise, but wages have stagnated or even atrophied.

Relatively minor element. In this light, we can see that what Adam Smith ultimately did, in creating his debt-free market utopia, was to fuse elements of this unlikely legacy with an unusually militaristic conception of market behavior characteristic of the Christian West. In doing so, he was surely prescient. But like all extraordinarily influential writers, he was also just capturing something of the emerging spirit of his age. What we have seen ever since is endless political jockeying between two sorts of populism—state and market populism—without anyone noticing that they were talking about the left and right flanks of exactly the same animal.

The main reason we’re unable to notice this, I think, is that the legacy of violence has twisted everything around us. It’s not just that war, conquest, and slavery played such a central role in converting human economies into market ones; there is literally no institution in our society that has not been affected to some degree. The story told at the end of Chapter Seven, of how even our conceptions of “freedom” itself came to be transformed, through the Roman institution of slavery, from the ability to make friends, to enter into moral relations with others, into incoherent dreams of absolute power, is perhaps the most dramatic instance—and the most insidious because it leaves it very hard to imagine what meaningful human freedom would even be like.

If this book has shown anything, it’s how much violence it has taken, over the course of human history, to bring us to a situation where it’s even possible to imagine that that’s what life is really about. Especially when one considers how much of our daily experience flies directly in the face of it. As I’ve emphasized, communism may be the foundation of all human relations—that communism that, in our daily life, manifests itself above all in what we call “love”—but there’s always some sort of system of exchange, and usually, a system of hierarchy built on top of it.

These systems of exchange can take an endless variety of forms, many perfectly innocuous. Still, what we are speaking of here is a very particular type of exchange, founded on precise calculation. As I pointed out at the very beginning: the difference between owing someone a favor and owing someone a debt is that the amount of a debt can be precisely calculated. Calculation demands equivalence. And such equivalence—especially when it involves equivalence between human beings (it always seems to start that way, because at first, human beings are the ultimate values)—only seems to occur when people have been forcibly severed from their contexts, so much so that they can be treated as identical to something else. For example: “seven marten skins and twelve large silver rings for the return of your captured brother,” or “one of your three daughters as surety for this loan of one hundred and fifty bushels of grain …”

This, in turn, leads to that great embarrassing fact that haunts all attempts to represent the market as the highest form of human freedom: that historically, impersonal, commercial markets originate in theft. More than anything else, the endless recitation of the myth of barter, employed much like an incantation, is the economists’ way of exorcising this uncomfortable truth. But even a moment’s reflection makes it obvious. Who was the first man to look at a house full of objects and immediately assess them only in terms of what he could get for them in the market? Surely, he could only have been a thief. Burglars, marauding soldiers, then perhaps debt collectors, were the first to see the world this way. It was only in the hands of soldiers, fresh from looting towns and cities, that chunks of gold or silver—melted down, in most cases, from heirloom treasures like Kashmiri gods, Aztec breastplates, or Babylonian women’s ankle bracelets (both works of art and little compendiums of history)—could become simple, uniform bits of currency, with no history. They became valuable precisely for their lack of history because they could be accepted anywhere, no questions asked. And it continues to be true. Any system that reduces the world to numbers can only be held in place by weapons, whether these are swords and clubs or, nowadays, “smart bombs” from unmanned drones.

It can also only operate by continually converting love into debt. I know my use of the word “love” here is even more provocative, in its own way, than “communism.” Still, it’s important to hammer the point home. Just as markets, when allowed to drift entirely free from their violent origins, invariably begin to grow into something different—into networks of honor, trust, and mutual connectedness—the maintenance of systems of coercion constantly does the opposite: it turns the products of human cooperation, creativity, devotion, love, and trust back into numbers once again. In doing so, they make it possible to imagine a world that is nothing more than a series of cold-blooded calculations. Even more, by turning human sociality itself into debts, they transform the very foundations of our being—since what else are we, ultimately, except the sum of the relations we have with others—into matters of fault, sin, and crime, making the world into a place of iniquity that can only be overcome by completing some great cosmic transaction that will annihilate everything.

Trying to flip things around by asking, “What do we owe society?” or even trying to talk about our “debt to nature” or some other manifestation of the cosmos is a false solution—a desperate scramble to salvage something from the very moral logic that has severed us from the cosmos to begin with. In fact, if anything, it is the culmination of the process, brought to a point of veritable dementia, since it’s premised on the assumption that we’re so absolutely, thoroughly disentangled from the world that we can toss all other human beings—or all other living creatures, even, or the cosmos—into a sack, and then start negotiating with them. It’s hardly surprising that the end result, historically, is to see life itself as something we hold on false premises, a loan long overdue, and therefore, to see existence itself as criminal.

Insofar as there’s a real crime here, though, it’s fraud. The very premise is fraudulent. What could be more presumptuous, or more ridiculous, than to think it would be possible to negotiate with the grounds of one’s existence? Of course, it isn’t. Insofar as it is indeed possible to come into any sort of relation with the Absolute, we are confronting a principle that exists outside of time—or at least human-scale time entirely; therefore, as medieval theologians correctly recognized, when dealing with the Absolute, there can be no such thing as debt.

Conclusion: Perhaps the World Really Does Owe You a Living

Much of the existing economic literature on credit and banking, when it turns to the kind of larger historical questions treated in this book, strikes me as little more than special pleading. True, earlier figures like Adam Smith and David Ricardo were suspicious of credit systems, but already by the mid-nineteenth century, economists concerned with such matters were largely in the business of trying to demonstrate that, despite appearances, the banking system really was profoundly democratic. One of the more common arguments was that it was really a way of funneling resources from the “idle rich,” who, too unimaginative to do the work of investing their own money, entrusted it to others, notably, to the “industrious poor”—who had the energy and initiative to produce new wealth. This justified the existence of banks, but it also strengthened the hand of populists who demanded easy money policies, protections for debtors, and so on—since, if times were rough, why should the industrious poor, the farmers, artisans, and small businessmen, be the ones to suffer?

This gave rise to a second line of argument, that no doubt the rich were the major creditors in the ancient world, but now the situation has been reversed. So Ludwig von Mises, writing in the 1930s, around the time Keynes was calling for the euthanasia of the rentiers:

Public opinion has always been biased against creditors. It identifies creditors with the idle rich and debtors with the industrious poor. It abhors the former as ruthless exploiters and pities the latter as innocent victims of oppression. It considers government action designed to curtail the claims of the creditors as measures extremely beneficial to the immense majority at the expense of a small minority of hardboiled usurers. It did not notice at all that nineteenth-century capitalist innovations have wholly changed the composition of the classes of creditors and debtors. In the days of Solon the Athenian, of ancient Rome’s agrarian laws, and of the Middle Ages, the creditors were by and large the rich and the debtors the poor. But in this age of bonds and debentures, mortgage banks, savings banks, life insurance policies, and social security benefits, the masses of people with more moderate incomes are rather themselves creditors.

Whereas the rich, with their leveraged companies, are now the principal debtors. This is the “democratization of finance” argument and it too is nothing new: whenever there are people calling for the elimination of the class that lives by collecting interest, there will be others to object that this will destroy the livelihood of widows and pensioners.

The remarkable thing is that nowadays, defenders of the financial system are often prepared to use both arguments, appealing to one or the other according to the rhetorical convenience of the moment. On the one hand, we have pundits like Thomas Friedman, celebrating the fact that "everyone" now owns a piece of Exxon or Mexico and that rich debtors are therefore answerable to the poor. On the other hand, Niall Ferguson, author of The Ascent of Money, published in 2009, can still announce as one of his major discoveries that:

Poverty is not the result of rapacious financiers exploiting the poor. It has much more to do with the lack of financial institutions, with the absence of banks, not their presence. Only when borrowers have access to efficient credit networks can they escape from the clutches of loan sharks, and only when savers can deposit their money in reliable banks can it be channeled from the idle rich to the industrious poor.

Such is the state of the conversation in the mainstream literature. My purpose here has been less to engage with it directly than to show how it has consistently encouraged us to ask the wrong questions. Let’s take this last paragraph as an illustration. What is Ferguson really saying here? Poverty is caused by a lack of credit. It’s only if the industrious poor have access to loans from stable, respectable banks—rather than to loan sharks, or, presumably, credit card companies or payday loan operations, which now charge loan-shark rates—that they can rise out of poverty. So, actually, Ferguson is not really concerned with "poverty" at all, just with the poverty of some people, those who are industrious and thus do not deserve to be poor. What about the non-industrious poor? They can go to hell, presumably (quite literally, according to many branches of Christianity). Or maybe their boats will be lifted somewhat by the rising tide. Still, that’s clearly incidental. They’re undeserving, since they’re not industrious, and therefore what happens to them is really beside the point.

For me, this is exactly what’s so pernicious about the morality of debt: the way that financial imperatives constantly try to reduce us all, despite ourselves, to the equivalent of pillagers, eyeing the world simply for what can be turned into money—and then telling us that it’s only those who are willing to see the world as pillagers who deserve access to the resources required to pursue anything in life other than money. It introduces moral perversions on almost every level. ("Cancel all student loan debt? But that would be unfair to all those people who struggled for years to pay back their student loans!" Let me assure the reader that, as someone who struggled for years to pay back his student loans and finally did so, this argument makes about as much sense as saying it would be "unfair" to a mugging victim not to mug their neighbors too.)

The argument might make sense if one agreed with the underlying assumption—that work is by definition virtuous since the ultimate measure of humanity’s success as a species is its ability to increase the overall global output of goods and services by at least 5 percent per year. The problem is that it is becoming increasingly obvious that if we continue along these lines much longer, we’re likely to destroy everything. That giant debt machine that has, for the last five centuries, reduced increasing proportions of the world’s population to the moral equivalent of conquistadors, would appear to be coming up against its social and ecological limits. Capitalism’s inveterate propensity to imagine its own destruction has morphed, in the last half-century, into scenarios that threaten to bring the rest of the world down with it. And there’s no reason to believe that this propensity is going away. The real question now is how to ratchet things down a bit, to move toward a society where people can live more by working less.

I would like, then, to end by putting in a good word for the non-industrious poor. At least they aren’t hurting anyone. Insofar as the time they are taking off from work is being spent with friends and family, enjoying and caring for those they love, they’re probably improving the world more than we acknowledge. Maybe we should think of them as pioneers of a new economic order that would not share our current one’s penchant for self-annihilation.

In this book, I have largely avoided making concrete proposals, but let me end with one. It seems to me that we are long overdue for some kind of Biblical-style Jubilee: one that would affect both international debt and consumer debt. It would be salutary not just because it would relieve so much genuine human suffering, but also because it would be our way of reminding ourselves that money is not ineffable, that paying one’s debts is not the essence of morality, that all these things are human arrangements, and that if democracy is to mean anything, it is the ability for all of us to agree to arrange things in a different way. It is significant, I think, that since Hammurabi, great imperial states have almost invariably resisted this kind of politics. Athens and Rome established the paradigm: even when confronted with continual debt crises, they insisted on legislating around the edges, softening the impact, eliminating obvious abuses like debt slavery, using the spoils of empire to throw all sorts of extra benefits at their poorer citizens (who, after all, provided the rank and file of their armies) so as to keep them more or less afloat—but all in such a way as never to allow a challenge to the principle of debt itself. The governing class of the United States seems to have taken a remarkably similar approach: eliminating the worst abuses (e.g., debtors’ prisons), using the fruits of empire to provide subsidies, visible and otherwise, to the bulk of the population; in more recent years, manipulating currency rates to flood the country with cheap goods from China, but never allowing anyone to question the sacred principle that we must all pay our debts.

At this point, however, the principle has been exposed as a flagrant lie. As it turns out, we don’t “all” have to pay our debts. Only some of us do. Nothing would be more important than to wipe the slate clean for everyone, mark a break with our accustomed morality, and start again.

What is a debt, anyway? A debt is just the perversion of a promise. It is a promise corrupted by both math and violence. If freedom (real freedom) is the ability to make friends, then it is also, necessarily, the ability to make real promises. What sorts of promises might genuinely free men and women make to one another? At this point, we can’t even say. It’s more a question of how we can get to a place that will allow us to find out. And the first step in that journey, in turn, is to accept that in the largest scheme of things, just as no one has the right to tell us our true value, no one has the right to tell us what we truly owe.

It's a fun rabbithole to explore, this gold thing. It comes as you from many different avenues that it truly becomes a rabbit warren trying to figure it out. I'd heard about it in 2013-14-ish but by way of the more obscure "truthers", not the mainstream ones everyone knows. Then came the reading and the books and.... Many different theories of who owned it, where it came from and why was it in NY but once you start investigating it - all those different theories seem to mesh into one huge story web with a Cecil B. DeMille-type cast. And all evidentiary. Have fun!

Mainstream:

https://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/09/22/rec.buried.treasure/index.html

September 22, 2001 Posted: 5:36 AM EDT (0936 GMT)

NEW YORK (CNN) -- Buried somewhere under the World Trade Center rubble lies a fortune.

https://nymag.com/news/9-11/10th-anniversary/gold/

Earlier in the morning, before the attack, an armored truck had made its way through an underground tunnel below the World Trade Center. Inside the truck was millions of dollars’ worth of bullion. Through a maze of underground tunnels, the truck had just left a vault in which Comex, the commodities exchange, kept thousands of gold and silver bars stacked on pallets, a warehouse of megariches beneath the city surface.

"Truthers" and books:

David Guyatt's book "The Secret Gold Treaty"

Book "Gold Warriors" Sterling & Peggy Seagrave (my fav)

Dr Michael Salla, Exopolitics.org https://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sociopolitica/esp_sociopol_bilderberg_40.htm " According to the U.S. Treasury, as of November 2011, China held 1.1 trillion dollars in U.S. treasury securities. ... In fact the U.S. trade policy with China has been meticulously thought out. There is growing evidence that it is payback for the CIA’s decades long covert use of China’s “black gold” - gold that does not appear on any international gold registry. China’s “black gold” has been hidden for over six decades in order to fund a globally coordinated set of covert projects hidden from public view by the CIA and a consortium of national intelligence organizations and transnational corporations - a Global Manhattan Project." Rumour has it that it was "hidden" below WTC.

And it was all over AboveTopSecret.com and BeforeItsNews.com and RumorMillNews.com (yeah I know they all sound fishy but there's actually a lot of good stuff amidst the rubble - and it's all subject to following the trail to prove it anyway, right?) DYOR kinda thing.