THE NEW ANARCHISM -Villagism, Pacifism, and the Legacy of Mohatma Gandhi

Crow Qu'appelle in conversation with Paul Cudenec

Hey everyone,

Given that the readership of this blog has been growing quickly of late, it occurs to me that many of you may be wondering what Nevermore is all about.

If so, I have good news! Paul Cudenec and I co-wrote a book which serves as a handy primer to what we call THE NEW ANARCHISM.

The book(let) is called THERE IS NOTHING MORE POWERFUL THAN AN IDEA WHOSE TIME HAS COME and was published by Winter Oak Press.

Because we want to get these ideas out into the world (and because we couldn’t afford to print physical copies), it is available for free download on the Winter Oak website.

If you find what we do valuable, we would very much appreciate it if you would be so kind as to consider supporting our work.

This work is meaningful to me, and I want to do full time, but I do need to make a living.

If you appreciate what Nevermore brings to the table, we would appreciate it if you would consider becoming a paid subscriber.

You can also make a one-time donation here on Buy Me a Coffee.

By the way, did you know that Nevermore has merch? Check out our shop here!

If any case, we are happy that our work has started resonating with a larger audience, and we hope that you guys will let us know what we can do to provide the type of content that you find valuable.

If you don’t care to support us financially right now, we also appreciate it when our readers take the time to leave comments. It helps us feel like we’re engaged in dialogue with you guys more that way. It makes our relationship more reciprocal, you know?

Anyway, I hope that you enjoy this sneak preview of THERE IS NOTHING MORE POWERFUL THAN AN IDEA WHOSE TIME HAS COME, which is the second of a series of interviews in which Paul Cudenec and I will discuss the philosophy which he lays out in The Withway. I invite the reader to check out the first interview here:

THE NEW ANARCHISM - Why an understanding of Metaphysics is essential for any truly Revolutionary Movement

Hey everyone, Given that the readership of this blog has been growing quickly of late, it occurs to me that many of you may be wondering what Nevermore is all about. If so, I have good news! Paul Cudenec and I co-wrote a book which serves as a handy primer to what we call THE NEW ANARCHISM.

Without further ado, I present:

Villagism, Pacifism, and the Legacy of Mohatma Gandhi

“I believe that if India, and through India the world, is to achieve real freedom, then sooner or later we shall have to go and live in the villages – in huts, not in palaces. Millions of people can never live in cities and palaces in comfort and peace”.

-Mohandas Gandhi

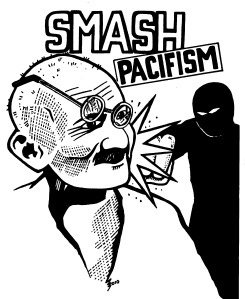

In recent years, the name of the once-revered Mohatma Gandhi has been dragged through the mud. Leftists of various stripes have assailed his legacy, accusing him of being a willing pawn of British imperialists. Anarchists have participated in this defamation, or revisionism, or whatever you want to call it. In 2011, Frank Lopez critiqued Gandhi´s pacifism in his influential documentary END:CIV. In 2012, Gord Hill went further, publishing a zine called Smash Pacifism, in which he attacks the legacies both of Gandhi and of Martin Luther King. And Peter Gelderloos and Derrick Jensen have also been hyper-critical of pacifism in their influential works How Non-Violence Protects the State and Endgame.

In the light of these developments, I read Paul Cudenec´s description of Gandhi´s vision of a post-industrial society with interest. I had been unaware of Gandhi´s philosophy of Villagism, which has a much more anarchistic character than I had previously been aware.

To give you an idea of this philosophy, I´ll cite a new quotes from Gandhi here.

“There is no doubt that most of our wants can be supplied by the villages. When we become village-minded we shall not want imitations from the West or machine-made products”.

“My idea of village swaraj is that it is a complete republic, independent of its neighbours for its own vital wants, and yet inter-dependent for many others in which dependence is a necessity.¨

¨My economic creed is a complete taboo in respect to all foreign commodities, whose importation is likely to prove harmful to our indigenous interests. This means that we may not in any circumstances import a commodity that can be adequately supplied from our country”.

Personally, I am not knowledgeable about India, and I generally try to refrain from having strong opinions on subjects about which I am uninformed. For that reason, I decided to interview Paul on the subject of Villagism, Pacifism and the legacy of Gandhi. We also touch on other subjects such as the historical roots of anarchism in anabaptism, Sufism, the Brethren of the Free Spirit, and the indigenous intellectual tradition of Turtle Island. Enjoy!

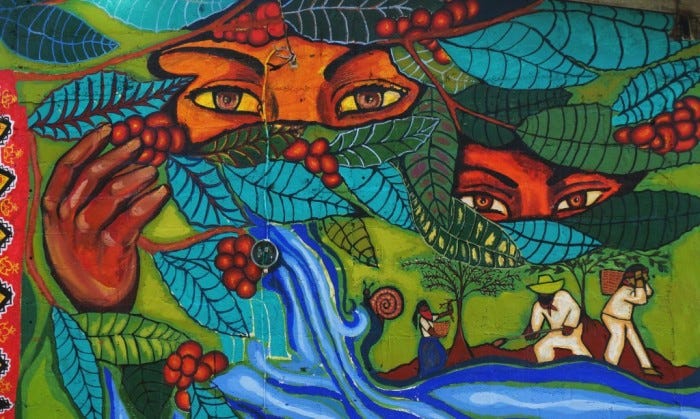

CROW - In The Withway, you speak of Mohatma Gand his philosophy of Villagism, which you define as a shared vision of decentralised communities based around traditional crafts and culture. This resonates with me because it is, broadly speaking, the goal of the indigenous sovereignty movement on Turtle Island. I remember, years ago, hearing someone describe the goal thusly. ¨There´s no sovereignty without food sovereignty, and there´s no food sovereignty without an intact land base. So we must defend the land.¨

Now I live in Chiapas, where the Zapatista movement asserts that ¨the land belongs to those that work it¨ and defends the interests of a network of autonomous villages.

So although I am only just encountering the term ¨Villagism¨ now, it seems to describe something that is already a core part of my philosophy.

Now, Gandhi is certainly a household name, and was a major inspiration to an earlier generation of anarchists (such as Ammon Hennessy and the Catholic Workers). Do you feel that his philosophy has been misrepresented in recent years?

PAUL - Yes, and deliberately so, I suspect. First of all, it was stripped of its anti-industrial and decentralizing aspects to be presented as merely a philosophy of pacificism and of Indian national independence.

Since the latter has long been a superficial historical reality (although India never really became free of the malignant imperial entity which has now mutated into globalism), it has been deprived of its radical edge and framed in a purely historical context, like the original slave trade.

We are meant to believe that, thanks to the benevolent forces of liberal-commercial progress (into which Gandhi has been somehow recuperated) all that colonial occupation and exploitation is now safely in the past!

Just to skip back to Gandhi's pacifism - for me, this was clearly the best strategy available to him. The sheer numbers of Indians were their resistance trump card.

Personally, I think we should avoid fetichizing either violence or non-violence. Each situation calls for its own response, to be determined by those involved on the basis of their own inner ethical compass.

CROW - What do you make of the recent efforts to cancel Gandhi? I think it's worth noting that anarchists such as Gord Hill have played an active role in this.

PAUL - I have heard a bit about this, but I haven't read the stuff, so I can't answer in detail. I would make two main points, though.

Firstly, what interests me are the ideas expressed directly by Gandhi and his colleagues, like the Kumarappa brothers, which have greatly inspired me. I recommend people go to those sources and read them, rather than relying on second-hand accounts which may well be designed to deceive.

The historian Carroll Quigley spells out how the imperial ruling clique, which owns pretty much everything today, has made a point of controlling not only the present (via the media), but also the past, via academia and the writing (and publishing) of history. When you throw in the extent to which so-called "radicals" have been corrupted by those same networks (on which I have written quite a lot since 2020), we are left with a bleak Orwellian picture.

The villagism, simplicity, self-sufficiency and decentralization proposed by Gandhi represent the exact opposite of the authoritarian transhumanist world totalitarianism sought by the system. It would make perfect sense for them to deliberately undermine Gandhi's thinking, via the ad hominem approach they so often favour in the absence of any real philosophical or ethical arguments.

Discrediting these ideas among those most likely to adopt them, such as anarchists, would be especially important, so the smears would have to be devised with that audience in mind. I see this sort of shallow "debunking" approach all the time regarding the organic radical thinkers whose legacy I promote.

It is always a favoured approach to claim that the writer in question was secretly working for the system all along - nothing like that to put off an actual radical! And people parrot these stupid lines, without knowing what they are talking about.

Go away and read George Orwell or Aldous Huxley, essay for essay, line for line, and tell me that you really believe they wanted to bring about the dystopias they were warning us about! It's absurd!

They could do the same thing to me and you, when we're dead and gone and unable to defend ourselves. There's a definite modus operandi there, which has been analysed with regard to Wikipedia, for instance.

History is re-written to suit the needs of the system. Once you realise that the system exists, that it knows no moral qualms, and that it is eminently capable of fabricating history, then frankly it becomes absurd to imagine that it would not do so!

Once you realise that many "radicals" and "anarchists" are fake, and controlled by the system, then you become very wary of narratives coming from that direction which only protect and reinforce the dominant worldview. Question everything!

CROW - As long as we are discussing Villagism, I think it would be appropriate to bring up the example of anabaptist groups such as the Quakers, Mennonites, Hutterites, and Amish.

If you are advocating for Villagism as a revolutionary strategy, I think that it behooves you to study the examples of these movements, all of which have been living exactly such an ideology for hundreds of years.

If I understand you correctly, you are advocating for secession from industrial society and the formation of autonomous communities which do not depend on the industrial system. Furthermore, you advocate for a type of spiritual perspective.

It sounds a lot like what you´re advocating for is a strategy of going Amish. How does your philosophy differ from that of the Amish and where do the two overlap?

PAUL - I don't know a lot about the Amish philosophy, I'm afraid, but if it's about communities becoming independent from the system, then I am obviously sympathetic. I am in contact with networks here in France that are aiming for the same thing - since the Covid moment, the interest and urgency has soared.

Of course, the big problem is that the system will not simply sit back and let people slip out of its control. Industrial society was only created in England in the first place by enclosing common land and thus forcing people out of their traditional lives of so-called subsistence. Uprooted and dispossessed, they were forced to accept wage slavery in the system's new factories.

Seeking autonomy today is also to declare war on the system. But if enough people, everywhere, try it at the same time (in the narrow window of concentrated resistance that the system has itself provoked), and are prepared to defend themselves to the very end, has the system got the physical means to make us all submit? I suspect not, which is why I consider this approach a cause for hope.

As far as spirituality goes, I don't think you can live simply, on the land, in a small stable community, and not feel the soulful sensitivity to place, people, belonging, landscape, animals, seasons and a slow passing of time, hinting at the eternal, that has been torn away from us by the modern industrial racket.

CROW - As you are aware, I was raised Mennonite, which is a pacifist anabaptist denomination of Christianity.

An important part of my upbringing was being aware of the history of my people. As you are aware, not all anabaptists were originally pacifists. There were revolutionaries who preached for full-on war against the Roman Catholic Church and the states with which it was allied.

These revolutionaries are known to history as the People of the Sword, whereas the People of the Staff, from whom I am descended, advocated for secession, economic self-suffiency, and refusal to serve in the military. It would be hard to argue against the fact that the strategy of the People of the Staff has yielded better results than that of the violent anabaptist revolutionaries who took over Munster in the 16th century. And this leads me to my interest in pacifism as an effective political strategy.

Whereas the People of the Sword have long since vanished, the People of the Staff have spread to every corner of the Earth. There are over two million Mennonites worldwide, with countless autonomous or semi-autonomous communities spread throughout the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Yet anabaptists are rarely mentioned in contemporary anarchist discourse. Why do you think this is?

PAUL - I think it just doesn't fit in with the narrow definition of anarchism today adopted by so many of its adherents, to the great detriment of the philosophy. Any form of religion or even spirituality is a complete no-no, for many comrades. Christian anarchism is regarded as strange and marginal.

CROW - One of the thing that I appreciate about your work is how you trace anarchist ideas back much prior to the French Revolution, when the word anarchism was invented. It should be common knowledge, I think, that anarchism is derived from anabaptism, but atheist anarchists seem to downplay this fact. Why do you think it is that anarchists have so long had such a limited interest in their own history?

PAUL - As you know, there is more than one way of seeing anarchism. The first book I ever read about the subject, many years ago now, was George Woodcock's classic 'Anachism', and there he mentions anabaptism as part of the movement's "family tree". Peter Marshall, in 'Demanding the Impossible' also traces the philosophy back to, and indeed beyond, that period, and it has always seemed obvious to me that anarchism was the continuation of something that already existed. That's how things work!

But there are others whose definition of anarchism is much narrower and confined to the political movement giving itself that name. That is also legitimate, but confusion is caused, as ever, by the use of the same word to describe different things.

I don't think you can separate anarchists' lack of interest in their movement's history from the general ignorance of history in contemporary society - or real history, anyway. The information people consume and share revolves entirely around what is happening right now, today, and the past is invoked merely to back up narratives which justify a particular present.

Some young identity-politics anarchists are now so trapped in their artificial techno-ideological bubble that it must, furthermore, be very difficult for them to identify with a past world inhabitated solely by "cisgendered" men and women who paid no attention to their pronouns and enjoyed no access to the internet.

CROW - In your book The Stifled Soul of Humankind, you trace anarchist ideas back even further than the Radical Reformation, proposing the theory that Europeans Crusaders may have encountered radical Sufi sects in the Middle East and brought these ideas back to Europe with them. Do you believe that Sufism is a major influence on anarchism?

PAUL - I think it goes deeper than that. Anarchism (or anarchy) is the manifestation of natural law in the human mind - it is the realisation that we are part of organic nature and that our individual freedom is, at one and the same time, necessary for the well-being of the communal whole and dependent on the well-being of the communal whole.

This deep knowing, which is part of the underlying innate pattern of the human mind, is expressed in different cultures, at different times, in slightly different forms and with different labels, such as Tao or dharma or asha.

Sufism was a continuation of this knowledge, fed by various ancient sources, which managed, by its association with the dominant regional religion, to avoid being crushed by power, or forced deep underground, in the way of European pagan survivals.

So Sufi ideals would have appealed to those Europeans in the same way that they appealed to me - as openings to an ancient mystical wisdom which had largely disappeared from view in Christian Europe.

There are definite traces of Sufi influence in medieval heresy, but these influences would also have merged with currents still surviving in Europe (not least within Christianity) to inspire the Brethren of the Free Spirit and the Cathars and the anabaptists and so on.

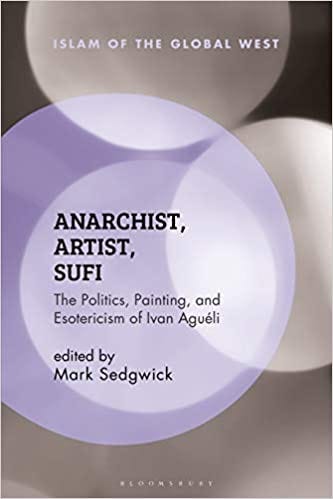

Sufism is very compatible with anarchism (as a recent book on Sufi anarchist Ivan Aguéli confirms) but it is not really the specificality of Sufism that is important here, as much as its role in reviving within us a sense of spiritual truth and freedom that is often buried beneath many layers of oppressive falsehood. Anarchy, for me, is another particular manifestation of this eternal gnosis, in a form suited to contemporary society.

However, Ihave to say that a certain kind of 2020s anarchism is no longer an appropriate vessel for this gnosis, as I am sure you would agree. In a way, this is the task you and I have set ourselves - to rescue anarchism from that oblivion and to enable it once more to become the ideological opening through which the light of ancient truth can light up the world today.

CROW - In the recent book by the late great anarchist David Graeber (R.I.P.), The Dawn of Everything, he and his co-author David Wengrow establish the major influence that the indigenous intellectual tradition of Turtle Island had in influencing the political thought of Europe.

In particular, the two authors rescue the Huron-Wendat orator Kondiaronk from obscurity, revealing him to be one of the great thinkers of the Enlightenment. This seems to further bolster your argument that there is nothing European about anarchism (except perhaps the word), and that the history of anarchism extends much, much further than is generally imagined. What do you think of Graeber and Wengrow's argument? Should we be looking to indigenous societies for inspiration on how human beings can organize themselves?

PAUL - Yes, their argument certainly rings true. For Europeans, it was as if they had rediscovered a way of living which no longer even lingered on in the collective memory, except in terms of a Golden Age or the Garden of Eden. They saw that people could live naturally, simply, happily, without all the artifice that had choked up their own world.

While the system that had enslaved them in Europe went on to enslave indigenous people elsewhere, a certain historical or anthropologial awareness was nevertheless sparked which led to deep-rooted criticism of what was now revealed to be a specific Western "civilization", rather than just some kind of permanent divinely-ordained hierarchical normality. Yes, of course indigenous societies can inspire us, not because we want to mimic their particularities, but because they reveal to us an old and healthy way of living, in harmony with the rhythms and patterns of nature, which all our ancestors once enjoyed and which will hopefully one day be enjoyed again by future generations.

FURTHER READING