What would sex-positive sex education look like?

In which I suggest we look toward anthropology for answers.

Hey Folks,

As you know, I’m very into political anthropology.

It’s not just me, by the way. There seems to have been quite a revival in interest in the subject lately, which I take as a sign that people are realizing that our entire civilization is profoundly fucked-up somehow.

Anarchists have been saying this for decades, by the way.

If you want to get yourself caught up with the latest and hottest trends in political philosophy, I suggest checking out the What is Politics? YouTube channel.

Anyway, one of the reasons to study anthropology is to get ideas about how human societies might organize themselves differently. Another is to gain another perspective on our own society. Comparative anthropology can help us to understand how profoundly abnormal our own society is.

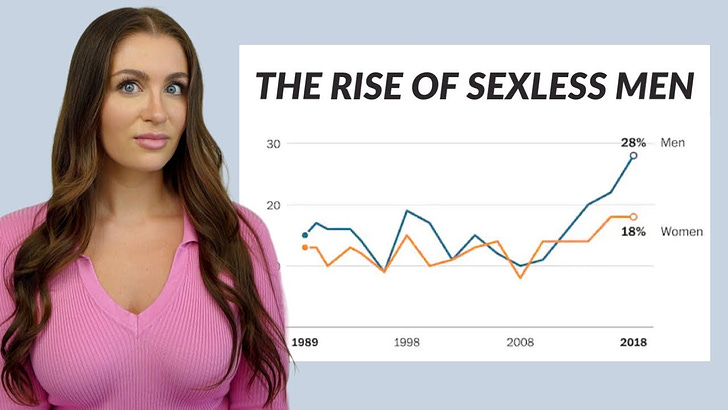

One of the ways that our society is abnormal is its attitude towards sex and marriage. Part of the problem is that young people nowadays are learning about sex through porn. Another part of the problem is that it has become normal for women to wait until they are thirty before deciding they want to have children, at which point about most of their years of fertility are behind them. Simply put, many women are waiting until it’s too late to decide that they want to have children.

This is by no means true for everyone, but it is true for many people, according to my mom.

My mom is now semi-retired, but she is a nurse who specializes in lactation. She has spent most of her career working in pre- and post-natal healthcare, meaning that she is in a very good position to understand female psychology as it relates to this issue. According to her, this is a big societal problem, but no one is talking about it.

A lot of people have come to the same conclusions, but there has yet to be any sort of movement to explore the roots of this problem, let alone to suggest solutions. This is matter of sex education.

Conservatives seem to want to go back to “the way things used to be”, but I don’t think that they’ve thought things all the way through. Sex education has been horrible for decades.

As my friend Kit Colt put it, the basic message of sex education in the 90’s was:

“You could get AIDS, you could get herpes, you could get gonorrhoea or chlamydia… you could get all these sexually-transmitted diseases, or worse… you could get a girl pregnant.”

Think about that. The government taught us all that getting pregnant was worse than getting a deadly disease. We were brainwashed to think that babies were at best a burden, at worst a curse.

Girls were taught that having a baby was a great way to “ruin your life”. Thirty years later, here we are.

Anyway, I just finished reading a very interesting ethnography called The Forest People, written by Colin Turnbull in 1962.

It is about a forest-dwelling Central African tribe of pygmies known as the BaMbuti. Their culture may be among the most ancient in the world, and they live in stateless societies without money. In short, they are anarcho-communists.

Furthermore, they are regarded by anthropologists as hyper-egalitarian, which is to say that they have full gender egalitarianism. Anthropologists nowadays are a bit reluctant to point out that many societies they used to call egalitarian are only really egalitarian between adult males. Truly egalitarian societies, in which men and women have equal decision-making power over decisions that affect them, are much less common. However, they do exist, and the NaBmuti are one example of such a society.

At the time when Colin Turnbull wrote The Forest People, the NaMbmuti lived alongside a tribe called the BaBira, who lived on plantations and belonged to a different ethnic group which was originally from somewhere else.

The following passage describes the attitudes towards sexuality of the two tribes, which could hardly have been more different. I would say the attitude of the villagers “sex-negative”, and the attitude of pygmies “sex-positive”. I would expect to find that hyper-egalitarian societies would be characterized by an attitude of sex-positivity.

Anyway, I thought that it would be very interesting for some of you out there. If this sounds like a topic you’d be interested in learning about, you can access the rest of this article by becoming a paid subscriber.

Enjoy!

ELIMA: THE DANCE OF LIFE

by Colin Turnbull, excerpted from The Forest People (1962)

With the Pygmies and the villagers coming into contact, both as individuals and groups, it was inevitable that over the years each should adopt some of the other's customs.

The contact between them was sometimes intimate and friendly… Most frequently its purpose was just a matter of barter, and at all times each regarded the territory of the other as a foreign place.

When a custom was adopted by one people, they gave it their own particular character and meaning, and frequently changed it so that it was all but unrecognizable, except through the common use of the original name. Such was the case with the molimo (the ritual of death), and such was also the case with the elima.

Who borrowed from whom is a difficult question, and perhaps not a very important one. The difference that emerges in the process of borrowing is much easier to see and adds much more to our understanding.

To both peoples, the elima is concerned with the arrival of a young girl at the age of maturity, her transition from girlhood to the full flowering of womanhood. This coming of age is marked more dramatically for girls than for boys by the physical changes that take place. Both Pygmies and villagers recognize the significance of the first appearance of menstrual blood, and both celebrate it with a festival which they call "elima." But there the similarity ends.

My friend Amina told me a great deal about the elima among the BaBira, and I learned more from older women in different villages that I lived in from time to time.

Everywhere, right through to the very edge of the forest, I found the same story among the villagers. Blood of any kind is a terrible and powerful thing, associated with injury and sickness and death. Menstrual blood is even more terrible because of its mysterious and regular recurrence. Its first appearance is considered by the villagers as a calamity — an evil omen. The girl who is defiled by it for the first time is herself in danger, and even more importantly, she has placed the whole family and clan in danger. She is promptly secluded, and only her mother (and, I suspect, one or two other close and senior female relatives) may see her and care for her. She has to be cleansed and purified, and the clan itself has to be protected, by ritual propitiation, from the evil she has brought upon them. At the best, the unfortunate girl is considered a considerable nuisance and expense.

It is generally assumed that the girl was brought into this condition by some kind of illicit intercourse, and her mother demands of her who is responsible. This is the girl's chance to name the boy of her choice, whether or not she has even so much as spoken to him. He is then accused and has to make suitable offerings which are necessary not only to help in the protection of the girl and her family, but also for his own protection, since he has been linked with her verbally, however untruthfully. He may then deny the charge, and if the girl's parents think he would make a suitable husband, there may be some litigation. Or they may consider him unsuitable, and let the matter drop. If he likes the girl and accepts the responsibility, this constitutes the first step toward official betrothal. If he disclaims all responsibility, then the girl has to try again; until she has a husband the danger is thought to remain.

The period of seclusion varies from tribe to tribe, and even from village to village. Sometimes it is just for a week or two; sometimes it lasts a month or more. And sometimes it lasts until the girl is betrothed and can be led from her room of shame to be taken away by her husband. At the final wedding ritual, she is ceremonially cut off from her family, and told that she is now her husband's responsibility and must fend for herself and not come running home every time she gets beaten. The point, of course, is that if she does this, her husband can claim back the wealth he will have already paid over in the expectancy of her fidelity and success as a wife and bearer of children. And by the time the disaster occurs her family will almost certainly have spent the money to obtain a bride for one of her brothers.

The whole affair is a rather shameful one in the eyes of the villagers, as well as a dangerous one. It is something best concealed and not talked about in public. The girl is an object of suspicion, scorn, repulsion, and anger. It is not a happy coming of age.

THE PYGMY RITUAL OF ELIMA

For the Pygmies, the people of the forest, it is a very different thing. To them blood, in the usual context in which they see it, is equally dreadful. But they recognize it as being the symbol not only of death but also of life. And menstrual blood to them means life.

Even between a husband and wife, it is not a frightening thing, though there are certain restrictions connected with it. In fact, the Pygmies consider that any couple that really wants to have children should "sleep with the moon." So when a young Pygmy girl begins to flower into maturity, and blood comes to her for the first time, it comes to her as a gift, received with gratitude and rejoicing — rejoicing that the girl is now a potential mother, that she can now proudly and rightfully take a husband. There is no mention of fear or superstition, and everyone is told the good news.

The girl enters seclusion, but not the seclusion of the village girl. She takes with her all her young friends, those who have not yet reached maturity, and some older ones.

In the house of the elima, the girls celebrate the happy event together. Together they are taught the arts and crafts of motherhood by an old and respected relative. They learn not only how to live like adults but also how to sing the songs of adult women. Day after day, they are reminded that they are leaving their childhood behind and are entering into a new and rich experience of life. They are instructed in the ancient songs and stories of the Pygmy people, and they learn from the life experience of their elders. At the end of their seclusion, they emerge as young women, their hair newly dressed, their bodies smeared with oil and powders, adorned with beads and glistening shells, and ready to join the adults in the great festival of the elima.

At this time they are not only admired and envied by their younger friends, but also by the young men who have been watching them from a distance. For among the Pygmies it is the girl who chooses her husband, and if she has not yet made up her mind, this is her chance to show off her charms and test the mettle of her suitors. If she knows her own mind, then she has already made her choice, and she and her family have been watching her young man with interest. If he has what it takes to win her, then he will be welcomed into the family, and his family will be glad to receive her wealth. If not, then she will tell him to go away, and the family will not feel so bad about losing the wealth they have already spent.

At the end of the festival, the girls are led away, each with her chosen husband, to be formally introduced to his family and to begin her new life as a married woman. And they leave behind them a new generation of girls, who will one day go through the same ceremony and take their place among the women of the forest.

The girl enters seclusion, but not the seclusion of the village girl. She takes with her all her young friends, those who have not yet reached maturity, and some older ones.

In the house of the elima, the girls celebrate the happy event together. Together they are taught the arts and crafts of motherhood by an old and respected relative. They learn not only how to live like adults but also how to sing the songs of adult women. Day after day, night after night, the elima house resounds with the throaty contralto of the older women and the high, piping voices of the youngest. It is a time of gladness and happiness, not for the women alone but for the whole people. Pygmies from all around come to pay their respects, the young men standing or sitting about outside the elima house in the hopes of a glimpse of the young beauties inside. And there are special elima songs which they sing to one another, the girls singing a light, cascading melody in intricate harmony, the men replying with a rich, vital chorus. For the Pygmies, the elima is one of the happiest, most joyful occasions in their lives.

And so it was with happiness that we all heard that not one but two girls in our camp had been blessed by the moon.

At first, it was just Akidinimba, daughter of Manyalibo's sister. Akidinimba was a notorious flirt who considered herself the most beautiful girl in the world. She was just sufficiently plump to be envied by less well-endowed girls, but not so plump that her maidenly figure was lost. She was particularly proud of her breasts, which were certainly the largest in that part of the forest, and she showed them off to advantage when dancing, by adopting an unusually springy gait. As her breasts bounced up and down, the eyes of all the bachelors followed their movement with pleasure. Everyone agreed that Akidinimba's elima would be a lively one.

But Manyalibo's niece was in no hurry, so for the first few days she remained in the hut of her cousin, Kondabate, and there were no particular signs of activity visible from the outside. Then we heard that Kidaya had also been blessed with the blood, and she went to join Akidinimba. Kidaya was a niece of Ekianga, and she was more modest than the really shameless Akidinimba. Kidaya was handsome rather than pretty, and she had a reputation for being able to beat up even the strongest youths if their advances were not welcome to her. So the elima promised to be exciting as well as lively.

The two girls each chose their personal assistants and called in all their young friends to join them in the hut of Kondabate and her husband, Ausu. Kondabate built on a special extension to accommodate them. This was in Apa Kadiketu, and not long afterward the elima was moved to the village, where it took over Ekianga's house. Mambunia, Masisi's brother, went with them to be the "father of the elima," to make sure that they were protected and properly cared for. Asofalinda, Kidaya's aunt, went as the "mother of the elima," to look after the personal needs of the girls, to see that they got the right food, and generally to act as chaperone. Mambunia was a bachelor, and Asofalinda a widow.

When we arrived at the village for the close of the molimo festival, the elima was well under way. The girls had already learned most of their songs, and they were now at the stage where they were taking a more active, even an aggressive interest in the eligible bachelors of the neighborhood. In the evenings, when they assembled outside their hut to sing, they were carefully guarded by their mothers and older sisters. But the girls and their attendants cast sly glances at the young men who always drew close to watch and listen. They whispered and laughed among themselves, and when they stood up to dance they often made it very clear by their gestures which boy had taken their fancy. Sometimes they chose at random simply to annoy a special lover, and boys often stalked away in a huff. That was a mistake.

At any time of the day, the girls were likely to emerge from the elima house armed with long fito whips. If you were close enough you could hear them plotting their strategy behind the door, but there was no escape once they burst out into the open. Any males, young or old, and particularly those who had shown annoyance at being teased, were liable to be chased and whipped by the eager young furies.

I myself was chased once, for a good half-mile down a forest trail, running as fast as I could. It was considered cowardly to run, but I ran with good reason, for to be whipped establishes an obligation to visit your assailant in the elima house. Once inside there is no need to do anything further, but you are subject to considerable attention if you refuse. And to get into the house, in the first place, requires no small amount of courage and strength. So I ran. Most other bachelors had less reason and no desire to escape, so they contented themselves with giving as good as they got, throwing sticks and stones at the girls, running around the village, dodging behind houses and through fields of sugarcane. The battles never lasted long, but sometimes they came to an abrupt end.

The girls often whipped old men or young boys, and in either case, it was generally considered a compliment and did not carry the same obligations that it would have done had they been eligible bachelors. But sometimes they hit too hard, and the old men resented this and shouted, while the boys simply screamed their heads off.

In one case, Mambunia would come out of his hut in a temper and send all the girls back to their house, and in the other case, Asofalinda would run amok among the girls, boxing their ears until they, in turn, cried like the children they had beaten.

But the elima beauties did not confine themselves to their own village. After all, most of the men there were relatives and so could not decently be invited into the elima house. Many strangers came to visit from other groups, but sometimes the attendance was disappointing. Then the girls would set out to visit one of their hunting camps. I followed them on one such escapade, having secured a promise first that I would be given complete immunity. It was a strange procession, the girls all oiled and painted to look their best, wearing grass skirts in imitation of the boys' initiation (an innovation that infuriated the villagers, who felt that their customs were being desecrated, and that caused open hostilities in the end), and carrying stout whips, twice as tall as they were. There were about eight of them in all, led, of course, by the irrepressible Akidinimba, bouncing her breasts up and down in a determined manner as she marched along the road, past the Station de Chasse, and over the bridge to the far side of the Epulu River. The villagers came out to look as we passed, but from a respectful distance. On other occasions, I have seen a party such as this dive into the midst of a group of village men and women, lashing out with all their might — not entirely in the friendly way in which they would whip, say, old Tungana, as a compliment to his virility.

On the far side of the Epulu, we climbed up the hill toward Eboyo, the sun beating down on us so that the chatter and laughter of the girls were almost stilled. But just before reaching Eboyo, we turned off, following a trail through an old plantation and into the forest. As the trees closed in around and above us, the girls began to sing. They sang loudly and proudly, marching with even more determination than before, their heads back, looking at the familiar leafy world that was theirs. One at a time, they sang ribald little solos, each trying to outdo the others, the rest joining in with a throaty chorus that cascaded downward like a waterfall. Each girl held her note as the others came in after her, swelling the volume of a great chord of music until they had no breath left. Then they all stopped together, sharply and suddenly, and cocked their heads to one side to listen for the echo sent back to them by the forest.

And so we continued our noisy, festive way, until we had climbed up and down the forest paths for about an hour. On this side of the Epulu, the forest was hilly, and at times the path was steep and difficult. But still, the girls sang. At last, we came to the edge of one of Sabani's hidden plantations, and the girls became silent. They made their way cautiously to the edge of a cluster of houses built in the middle of the plantation. This was where some of Sabani's relatives lived when they were keeping an eye on planting or harvesting activities. Akidinimba explained, in a gusty, confidential whisper, that her very special boyfriend, Pumba, would probably be there. She was very much in love with him, she said, far more so than with any of the other boys. And she wanted him. The only trouble was that he did not seem to want her.

Having discovered that Pumba was indeed there, dozing on a chair in the baraza of one of the houses, the girls entered the village with a rush, shouting and yelling and brandishing their whips. Pumba awoke with a start, but he was too low down in the chair and could not get up in time to escape. He was plainly terrified because in her determination to get her man, Akidinimba had detailed all the other girls to go for him alone. When Pumba finally managed to break away and run blindly into the safety of the hut, slamming the door shut behind him, his body was covered with long angry welts, some of which were bleeding. Akidinimba wiped her nose with the back of her arm and smiled grimly. Well pleased with her success, she simply sat down outside the door waiting for Pumba to emerge. Pumba knew that he was no match for a girl with such patience and perseverance. He opened negotiations from the other side of the locked and bolted door.

Akidinimba was in no hurry, so she carefully examined the door and the single window, to see if there was any chance of breaking in. But the door was stout, and the window was tightly closed by a wooden shutter. So she decided, with some statesmanship, to negotiate. In return for a promise that Pumba would be allowed to emerge free of any danger of further attack and free of any other obligations, she extracted a reluctant promise that he would attend the final stages of the elima back at Camp Putnam. A very downcast Pumba emerged and immediately started complaining that there had really been no need to beat him quite so hard. The girls asked him where the other Pygmies were, and he pointed across the plantation to the far side, where the forest stood out darkly into the blue sky. The girls told him to stay behind and not to try and warn his friends. They then set off, this time with Kidaya to the fore, picking their way across the tangle of fallen trees slowly and silently. On the far side, we entered the forest and continued southward for a short while. Kidaya, plotting her strategy like a general, sent out a couple of scouts. As a result of their report, we veered around to one side until we came to a slight rise. From the top of this, we looked down through the trees across a leafy floor, completely bare of any undergrowth except for a few ferns. Below us lay a typically picturesque Pygmy camp, shimmering in the haze of smoke from innumerable fires. It was built in two circles, joining each other as if in an attempt to become one. We could hear the idle chatter of men and women as they lay on their beds or on their hunting nets, dozing in the midday warmth. A dog wandered lazily from hut to hut, sniffing hungrily, confident that his masters were far too sleepy to bother him. The sun, directly overhead, came down through the trees in irregular, jagged shafts, so that parts of the camp were bright, others in almost total darkness. It must have been quite an old camp, for all the leaves on the huts were dry and brown.

We crept right up to the nearest hut without being seen, and then Kidaya ran lightly across the clearing and gave the sleeping youth of her choice a sound thwack with her whip. He leaped up, not so much in fear or anger as in surprise and in shame that he should have been caught. He grabbed for his bow and picked up a small stone which he fired back at Kidaya as he ran away. Kidaya laughed with delight. This was a sure sign that her overtures had been accepted.

The whole of the camp was awake before the rest of the girls had had time to whip more than a few boys, and it soon became alive with lashing whips and flying sticks and stones. The women and children crept into the backs of their huts for shelter, while the men ran from rubbish dump to rubbish dump, gathering the banana skins they used as ammunition. When they could not find any, they used whatever came to hand. A slice of banana skin fired from a taut bow at close quarters can be quite painful, and the girls found that the boys were putting up a good fight. So they picked up a few vine baskets that had been left lying around and using these as shields they advanced on their quarry.

The fight got more and more fierce, and at one time the boys managed to drive the girls right back into the huts. Then they stood at the entrances and fired their pellets of banana skin inside, giving rise to squeals of anguish. But Kidaya was too tough to be done down so easily. She emerged from her shelter without even a basket for protection and made a dash for the nearest fire. As she bent down to pick up a burning log, her particular boyfriend fired a pellet that struck her on her buttocks with a smack. Kidaya spun around and hurled the log with all her might; then she rubbed her backside affectionately and smiled. The other girls also began throwing logs, and soon there was hardly a fire left in the camp, and burning logs were scattered everywhere. The men retreated to the outskirts of the clearing and stood uncertainly, peering around trees or over the tops of huts, their bows and banana skins at the ready.

But the girls felt they had achieved their end. Each one had marked her victim, who was bound by the strongest bonds of self-respect to respond to the challenge and brave the elima house itself. Pumba, who had followed at a safe distance, sat disconsolately on a log that Akidinimba had thrown at him in a friendly way, and he did not even look up as we left.

The girls sang all the way home; even when they left the forest and made their way back across the Epulu, gleaming orange and gold in the late afternoon light, they sang. They sang so that everyone should know that they were the Bamelima, the people of the elima, girls who had been blessed with the blood and were now women.

There were occasions when the mood was different. One evening in particular, after a relatively quiet day, nearly all the women of the group gathered together outside the elima house. It was toward the end of the time that had been set, in an arbitrary fashion, for the duration of the festival. The Pygmies felt they had been in the village long enough, and the elima was interfering with their hunting. As much as the young men enjoyed hunting, the attraction of the elima house offered strong competition. If the boys were away too long, due to pressure from their parents, the girls complained that they were not being treated properly. Everyone agreed that this was an insoluble conflict, unless the elima was either brought to an end or moved out to the forest. It was not only the boys that were away from the hunt, but also the women and girls, who would otherwise have been gainfully employed gathering and helping to drive more animals into the men's nets. And the women said they were having far too good a time in the village. So it was decided to bring the elima to an end.

During this time, the older women paid more and more attention to what was going on and gathered almost nightly outside the house to join in the singing. But one evening was different in that almost every woman in the group was there. There were even some women from Cephu's group, which had temporarily detached itself and was now some miles away. They gathered early, before it was fully dark.

The bright blue sky was deepening without any of the wild tinges of color that so often come at dusk, and the tiny puffs of cloud that drifted across remained a shining, fluffy white, even when the sky was almost black.

The women brought sticks of fire with them, and some of them cooked and ate their evening meal right there outside the elima house; others just sat around and gossiped, huddling close to the fires from habit, though in the village, it was still warm. Inside the house, the girls were singing, but the women outside did not join in. The men sat before their huts, watching and waiting. Finally, the door opened and the girls trooped out. The younger ones came first, their bodies decorated with modest blobs of white paste made from clay; then came Akidinimba and Kidaya and their attendants, resplendent and magnificent, yet strangely shy. They must have spent hours working on themselves and one another, for they were covered with elaborate patterns skillfully drawn with fingers and thin sticks, also using the white clay. Akidinimba had taken particular trouble to paint her breasts with intricate circles of lines punctuated with blobs, something like a grapevine gone to seed, whereas the more demure Kidaya had concentrated on her buttocks, and these were covered with a hundred carefully painted little stars. Each girl had her favorite style, and each was different. They looked around coyly, to make sure they were being admired, and sat down at the edge of the group of women.

They began singing then, together with the women, much more seriously than they had ever done before. They sang as though they were women. They sang right through the evening and now and then stood up and danced in a bashful circle around one of the fires. They sang songs whose words had no particular significance, but which in themselves were of the greatest significance, being songs sung only by adult women. That was why so many of the mothers and grandmothers had assembled, to welcome their daughters into their midst again, no longer as children, but as friends and partners in adult life. Some of the women looked sad, for they knew that this meant that the girls would soon get married, and then they would almost certainly leave to join their husbands in other camps.

Akidinimba was very different from her usual boisterous self. She was still self-assured, and she bounced her breasts up and down as flagrantly as ever, but perhaps she was subdued by the thought that she was no longer the leader of a group of young girls, but only a young and inexperienced member of womanhood, with all the responsibilities this entailed. Kidaya too was thoughtful. While the others sang, Kidaya sat with her back to them, fondling a large clay cooking pot. She tapped on it with her fingers, keeping time to the music. Then she drew it close and held the mouth of the pot against her stomach, bending her head down to listen to the effect. It evidently pleased her, because she continued the experiment by taking hold of her breasts and forcing them into the mouth of the pot, squirming around until she was comfortable.

Then she moved her body rhythmically, producing a variety of curious sounds, not only in the tone of the drumming of her hands, but by making sucking noises as the air was forced in and out. When she tired of that, she put the pot between her knees and sang quietly into the mouth of it, getting a deep reverberating effect. This sounded so much like the molimo that the men started, and one of the women turned and said something sharply to Kidaya. Kidaya herself was a little startled and put the pot away from her. She relapsed into a thoughtful mood, slowly and deliberately rubbing herself with her hands, wiping off all the beautiful decorations so laboriously painted on her body by her friends. When the singing ended and the girls retired for the night, Akidinimba was still as decorative as when she first appeared, but Kidaya was just a mass of streaked and dirty gray. And there were tears in her eyes.

During the last week, the elima battles reached their highest pitch, both sides making the most of the opportunity while it lasted. The elima was, on the surface, a pretty happy-go-lucky affair, and what went on inside the hut was best left to the imagination. But in fact, it all had a very definite purpose, and was closely supervised by the watchful eyes of Asofalinda and Mambunia. For the Pygmies, the elima is not just a puberty rite for girls; it is a celebration of adulthood, and just as much for boys as for girls. For Akidinimba and Kidaya certain physical changes had taken place which marked them as women, but for boys, there are no such self-evident changes. They have to prove their manhood. Village boys do this by entering the initiation schools, but even though Pygmies enter the same schools, it is for a different purpose, quite unconnected with adulthood as they see it. For them, the elima serves the purpose, or at least a part of it.

In the elima, the boy has to show considerable courage to fight his way into the house after he has been invited. In the last week, the women maintain constant guard outside, and they are well supplied with all sorts of ammunition. If they want to keep any particular boy away from their daughters, they are perfectly capable of doing it. And when a boy finally succeeds in breaking his way through, he still has to face a possible beating from the girls inside. If he has not been invited by having been beaten beforehand, he will certainly have to go through it now.

As well as this, in order to prove himself a man, the boy has to kill "a real animal." That is to say, not a small one, such as a child might kill, but one of the larger antelopes, or even a buffalo, so proving that he is not only capable of feeding his own family but also able to help feed the older members of the group who can no longer fend for themselves.

Once a boy has gained access to the elima hut, he may flirt or even sleep with the girl who invited him. The elima gives an opportunity for boys and girls to get to know each other intimately, and such friendships often end in marriage. On the other hand, it gives two lovers a chance to discover that they are unsuited to each other before becoming betrothed officially. From what I was told by older men and women as well as by the bachelors who took part in this elima, it is even possible to have intercourse, but with certain restrictions. These restrictions must be effective in preventing conception because nowhere have I ever heard of a girl becoming pregnant in an elima house. A boy may sleep with a girl only if she consents.

The tacit consent of her mother has already been given by his having been allowed to gain access to the elima house. If he sleeps with her then he must not leave the house and has to stay there until the festival is over, subject to the same restrictions as the girls. But he may decide on just a mild flirtation. Or he may — and this is considered a master move — simply turn around and leave the house without having paid the slightest attention to any of the girls. Whatever happens, there are always young women, such as Kondabate, to keep an eye on their younger companions and see that they do not get into trouble.

The conclusion of this particular elima was an anticlimax. The Pygmies are not a ritualistically minded people; to them, the important thing about any festival is that they should openly express their emotions and accept the realities of whatever situation the festival marks. Instead of living in constant fear of the spirits of the dead, performing elaborate rituals to remove the souls of the departed as far away as possible and as quickly as possible, the Pygmies sing in their memory for months on end, during the molimo. And so, during the elima, they sing to celebrate the blessing of potential motherhood conferred on the fortunate girl or girls. The month or two that the festival lasts give them time to adapt themselves to the new situation, but they have no need for elaborate ritual acts. When the girls appeared that night and sat down with the women and sang with them before all the camp, that was a formal public acknowledgment of their new status as women. And yet the elima dragged on for several days afterward.

Part of the reason, of course, was that if they ended with a feast, in the tradition of the villagers, the villagers would be so pleased that they would probably contribute most of the food. And so it was in this case. For all other practical purposes, the elima had come to an end the night they sang together. But the girls had another reason; they wanted to placate the villagers. Sabani in particular had been extremely upset about the nonorthodox way this elima had been conducted. He, and many others, felt it was wrong for the girls to go wandering about from village to village, sometimes sleeping overnight in camps several miles away. This was unheard of. It was, to the villagers, as though a colony of lepers were wandering at large. But even more they resented the liberties the girls took with village custom. There is a certain dress that village elima girls are meant to wear because the special leaves of which it is made have the magical power of protection; other dress is ineffective and invites disaster. The Pygmy girls, however, found that the ineffective leaves were far more attractive. As they themselves said, "This plant makes such pretty skirts; why should we make ourselves ugly with that plant? This is a time to rejoice." They also liked to imitate the village boys' initiation, and this so infuriated and worried the village traditionalists that they threatened to invoke the most powerful curses on all the girls. And so the girls put on a traditional ending, village style, to appease them. On a Sunday morning, they came out of their house as soon as the first light of dawn flecked the sky with gold. They went down to the banks of a forest stream, where it widened out into a silent pool, and bathed themselves in half-hearted imitation of an elaborate village ritual. Then they oiled their bodies and donned oily new bark cloths and returned to dance in the village. They danced in a tight little circle while the women cooked the food. The villagers came to watch approvingly and to see that the food was properly distributed, for only certain people may eat it. They also made sure that all the leaves which had been used as a sleeping mattress in the elima house were thrown away and the house cleaned thoroughly. In this way, they satisfied themselves that no harm would come to "their" Pygmies. The ancestors would be appeased by the feast, and the evil spirit that hovered around the unclean girls would be driven away.

The girls found it all rather tedious and boring, and as soon as they were able, they broke off from their dancing and went wandering around the village. Akidinimba was in search of Pumba, who had failed her badly in the final ceremony. The others visited from house to house, in the hopes of gifts and compliments. The older women sat around and enjoyed the food for as long as it lasted; then they broke up and went about their business as though nothing had happened.

The men, for some time, had been talking about where they would build the next hunting camp.