CONSENSUS: WHEN IT WORKS AND WHEN IT DOESN'T

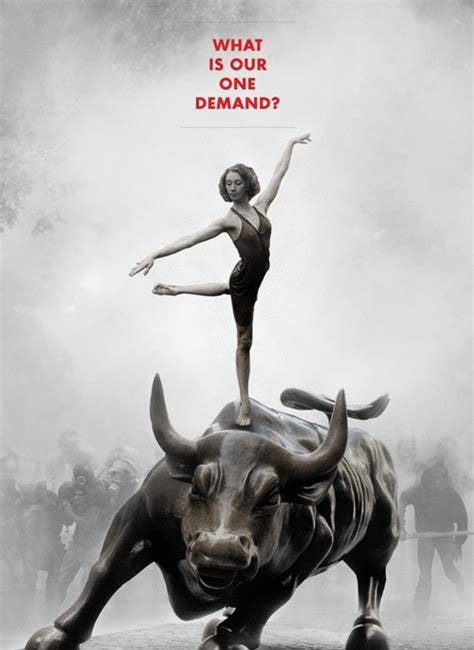

How Consensus Spread from Quakers to Feminists to Anarchists to #OccupyWallStreet

Hey Folks,

So, lately I’ve been doing a deep dive into Occupy Wall Street, trying to understand what went wrong.

So far, my biggest takeaway has been that Occupy’s biggest failure was its refusal to make demands.

Some people will tell you that Occupy failed because the organizers decided early on to use General Assemblies to make decisions by consensus, and that it simply didn’t work. I don’t disagree with this assessment. I participated in Occupy Ottawa, and I got real sick of the GAs pretty dang quick.

Because their first encounter with anarchist decision-making was negative, many people reached the facile conclusion that “consensus doesn’t work”.

My reason for writing is to make a simple point: sometimes consensus does work, and we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Today I want to put consensus process under the microscope and try to figure out when it works and when it doesn’t.

To do that, some historical context is helpful. It’s important to understand that the intent of the original organizers of Occupy was to revive the spirit of the Global Justice Movement, a.k.a. the anti-globalization movement.

The decision to use consensus decision-making at General Assemblies was made by people familiar with how activists did things during the era heyday of the millennial anarchist movement. You know - the Battle of Seattle, the Battle of Quebec, all of that.

Back in the nineties, anarchists developed ways of organizing that avoided the top-down, hierarchical structure that then typified the Left.

Consensus decision-making was seen as an anarchist alternative to Robert’s Rules of Order, which is how trade unions usually make decisions.

I now think it was a mistake that General Assemblies could have worked in a setting like Occupy, where most people were unfamiliar with consensus decision-making process.

This is different from saying that “consensus doesn’t work”. If you look at actually-existing stateless societies, past or present, you will find that they do make decisions by consensus, and have for millennia.

David Graeber’s anarchism was based on the two years that he spent doing anthropological fieldwork in Highland Madagascar, where consensus process is a deeply-embedded part of Malagasy culture.

Anarchists are sometimes accused of a fanatical and quasi-religious devotion to consensus process, and there is some truth to this.

This makes sense when you realize that consensus process, as practiced by anarchists, can be traced back to the Quakers, a pacifist denomination of Christianity in which consensus is a fundamental part of their religious practice.

According to one Quaker YouTuber, their practice is about “looking for obedience to the Will of God.”

If you watch this video, you will understand what was going on at Occupy better.

Does the quasi-religious nature of consensus process make more sense now?

If you believe in the basic premise of anarchism, which is to say that you believe that it is possible for humans beings to get along with the threat of violence to keep us all in line, you believe in consensus.

But as Occupy made abundantly clear, sometimes consensus process definitely doesn’t work. That’s indisputable.

My conclusion is that consensus only works when there is a culture of consensus, and that a culture of consensus takes time to build. It can’t be summoned into being overnight amongst a loose collection of people who barely know each other. And that’s to say nothing of undercover cops, wingnuts, sectarians, and political parties.

Consensus takes time to wrap your mind around, and I think that it would be a damn shame if people walked away from Occupy concluding that “consensus doesn’t work”. But it does have certain drawbacks. It is susceptible to sabotage by malicious actors, for instance. It works best when everyone present earnestly desires to submit their individual wills to the best interests of the Greater Good. For this to work, people have to be already on the same page about exactly that Greater Good is. This is why having a basis of unity is so important.

Did Occupy have a basis of unity? If so, what was it?

At the end of the day, consensus works when people have common goals, good intentions, are reasonable, and act in good faith. Take away any of those ingredients, and you’ve got a recipe for frustration.

Despite the drawbacks, I am pro-consensus, which is to say that I am pro-consensus-building. That should be the goal of everyone who wants to see a more peaceful world.

Consensus is often seen as aiming at a type of unachievable uniformity of thought, but this is fundamentally wrong. Anarchists do not pursue ideological conformity as a political goal. They aim at social relations in which no one group forces its will upon others. Simply put, the goal of consensus is social peace.

I’m not as hardcore as the Quakers are, by the way. To me, consensus does not mean reaching decisions that everyone loves. It is about reaching decisions that everyone can live with. More precisely, it is about reaching decisions that no one violently objects to. That’s kind of key if you want there to be less violence, wouldn’t you say?

What should Occupy have done differently? Well, obviously, that’s something that I’ve been giving a lot of thought to. I still haven’t reached definite conclusions, but I’ve been getting a lot out of your comments. So please, keep them coming!

Today’s selection is a brief history of how consensus decision-making arose over the course of the past five decades. As previously noted, it originated with Quakers, who were heavily involved in anti-war organizing during the Vietnam War, as well as the civil rights movement.

It was later adopted by feminists in the 1970s, and from there spread to the Global Justice Movement. It was also popularized by the success of the Zapatistas, who have their own form of consensus decision-making based in their traditional Maya culture.

It’s worth noting that almost all Zapatistas are devout Catholics who revere the Virgin of Guadelupe. I bring this up to make the point that it seems that consensus process tends to appear as part of a package that includes spiritual faith.

What I have for you today is excerpted from David Graeber’s Direct Action: An Ethnography. It is a dialogue taken from a workshop in May 2000, at the height at the Global Justice Movement. I believe it shows that the understanding of consensus process was much more sophisticated at that time then it was during Occupy.

If you don’t know what an ethnography is, by the way, it will only take you two minutes to find out!

I found this time capsule very interesting, and I hope you do too!

For a More Joyful World,

Crow Qu’appelle

CONSENSUS: WHEN IT WORKS AND WHEN IT DOESN’T

by David Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography

CONSENSUS AND FACILITATION

Let me turn now to some of the ethnographic baselines: meeting dynamics, consensus, and the art of facilitation. As promised, I will begin with the first facilitation training I myself attended, in the spring of 2000. This was a [Direct Action Network] training: since DAN continually rotated facilitators, it was felt everyone in DAN should at least be capable of playing that role. The crew consisted of three trainers, Mac and Lesley, the two Toronto natives who had been with NYC DAN since its inception, and Jim, a fortyish activist then working with Hudson Valley DAN, along with about a dozen activist trainees. All were relatively recent DAN recruits, ranging from Chris, a seventeen-year-old punk guitarist, to Nat, a woman in her seventies, long active in Marxist groups, who had become increasingly involved in anarchist ones over the last few years. Everyone had at least some experience with consensus process, and was familiar with at least some of the theory behind it.

Facilitation Training, Charas El Bohio

Sunday, May 21, 2000

[We start with a go-round where everyone, the three trainers and eight or nine trainees summarize their own experience with consensus, which ranges from working in food coops or cooperative bookstores to direct action training at A16 or observing spokescouncils in Seattle. You never know, Jim observed, when you might be in a situation that requires knowing how to facilitate—especially in smaller groups. There are some people who are just naturally good facilitators, but anyone can learn to do it, and, if nothing else, it’s not fair to expect the same people to have to do it all the time.]

[Lesley explains the agenda, pointing to a sheet on butcher paper taped to the wall.]

AGENDA

INTRODUCTION AND EXPERIENCE (10 min.)

WHAT WORKS AND WHAT DOESN’T (20 min.)

CONSENSUS—WHAT IS IT? (20 min.)

FACILITATION TOOLS (30 min.)

ROLE PLAY (10 min.)

DAN AGENDA (20 min.)

FEEDBACK (open)

Mac: I thought maybe we should start explaining why we’re organizing the training this way. We’ve kind of based our approach on popular education models where the idea is first you build a common analysis of how all of us see something—in this case, consensus—and then try to put that analysis into effect.

Lesley: That’s the idea, anyway. We’ll see if it actually works.

Mac: Then the model of how to do a workshop, we got from this book… [he hands out photocopies] Actually, we’ve never done this before, so it’s kind of an experiment. If it doesn’t work, we can always try something else.

WHAT WORKS? WHAT DOESN’T?

Jim: Okay, so, shall we start by asking people to talk about particularly effective forms of consensus decision-making they’ve observed, moments or approaches or techniques they thought worked really well, and what they liked about them? Then later we can move on to things that didn’t work so well.

Neala: I really like it when you take a little time at the beginning of a meeting to get to know each other. In a lot of meetings; everyone just jumps into the matter at hand, and there’s no way to set people at ease with each other, establish a sense of mutual peace, begin to develop the sense of a group mind.

Jim: So you’re saying an icebreaker of some sort?

Christa: Yes, whether it’s a listening exercise, where everyone pairs off and one is supposed to talk for one minute about something that’s been on their mind a lot that day, and the other isn’t allowed to say anything, but just has to listen—and then they switch off. Or something silly, like when everyone goes around in a circle and says what kind of animal they’d most like to be.

Sara: Or if it’s people who don’t know each other, just why they decided to come to the meeting.

Neala: Or what they’d like to see come out of it.

[Lesley has a blank sheet with “works/doesn’t work” at the top, and a magic marker, which she is whimsically waving in the air. She stops and writes “ icebreakers.” ]

Sara: I really like brainstorming sessions—what do you call it? “Popcorn.” When you set aside ten minutes when everyone gets to just call out ideas, whatever comes into their heads, no matter how stupid or ridiculous, and no one is allowed to comment on or criticize them, but can only call out one of their own. It’s times like that when I’ve felt I’ve really been in the presence of a group mind… well, especially when after the brainstorming session, you can actually start to patch together a proposal that brings all the best ideas together.

Mark: Restating proposals. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve sat through a ten-, fifteen-minute argument and it turned out that the only reason people were arguing is because they didn’t understand what was actually being proposed. People keep raising all sorts of concerns and objections that end up proving completely irrelevant once they’re reminded of the actual wording of the thing.

Lesley: [pen in hand, brow furrowed ] Now, that’s sounding like it might actually be for the “what doesn’t work” column. What do you think?

Christa: Why don’t we put it on both: “losing track of the proposal” on one side, “restating” on the other. [She does.]

Walter: I think it’s really useful when the facilitator steps in to remind everyone of their commonalities—whether it’s the principles of the group, or the reasons we’re trying to come to agreement on something to begin with. I’ve seen several times when it seemed everyone was at loggerheads over some minor point, or it was descending into some kind of stupid pissing contest, and if you have a skillful facilitator, they can step in to subtly remind everyone why they’re all here in such a way the whole issue just melts away and seems stupid.

Megan: Or more generally, when the facilitator is able to make sure everyone stays in problem-solving mode rather than debate mode. (Maybe you should write that.)

George: And while we’re at it: when the facilitator remembers to clarify when they’re speaking as facilitator, and when they’re giving their own opinion. I think it’s really important to have some phrase like “let me call on myself here” to show they’re now speaking as a member of the group, not as the person conducting the meeting.

Mac: And even that should be kept to the minimum. In DAN we always tell people that if they’re going to be bringing a proposal before the group, they can’t also facilitate that meeting.

Christa: Maybe that should be on the “doesn’t work side” too—when facilitators offer their own opinions…

George: …or don’t make it clear they are not doing so as facilitator.

Lesley: I’ll just put it on both sides again.

Jim: So I’m thinking maybe there’s no point in dealing with good process first, then bad process—maybe we should just run them both together, since that’s what we’re doing anyway.

[Before long we have created a fairly substantial two-column list, with a particularly long list of potential problems—lack of time limits, people who like to hear themselves speak, biased facilitation, speculative discussions on what to do based on contingencies that never end up having any bearing on what actually happens, bad vibes, breakdown of trust—and a number of additional good process ideas, from maintaining gender parity among speakers to the importance of having someone around to greet and orient new people who don’t understand the process.]

WHAT IS CONSENSUS?

Mac: Well, that was useful—part of the reason we like to start that way is just to give us ideas about how to improve our own process in DAN.

So, next we were going to talk a little bit about consensus, what makes it different from other forms of decision-making—particularly voting and majority rule. I’m going to start by throwing out the way that’s most different for me, which is that consensus as process. Voting is just a way of making decisions. The fact that you end things with a vote doesn’t necessarily tell you anything about the process that leads up to the vote: though usually it’s some kind of formal debate, Robert’s Rules of Order. Consensus is not just a way of coming to a decision, or, really, not even primarily a way of coming to a decision. It’s a process. A way for people to deal with each other which puts the emphasis on mutual respect and creativity, and which tries to make sure no one is able to impose their will on others and that all voices can be heard. As a process, it’s not even necessarily the most efficient way of coming to a decision. I think—I guess most of us think, if we’re involved with DAN—that it’s the process that will be most likely to produce the wisest decision, but I’d actually say that even if sometimes it doesn’t, it’s more important to reach the decision through a truly egalitarian process than to come up with the absolute ideal course of action every time. Decisions can usually be changed later anyway. And there are times when I’d even say it might be better not to reach a decision at all.

Now, there are as many styles of consensus as there are groups. Groups like DAN use a fairly formal process—though some groups use a much more formal one—other, smaller groups are much more informal in their process.

Jim: Though you know the degree of formality doesn’t only depend on the size of the group, it’s also a matter of familiarity. I’ve seen pretty large groups who’ve known each other for years, and who are used to the process, who usually dispense with the formalities entirely.

Lesley: Also: we’re not saying consensus is always necessarily going to be the best way to do things. Sometimes efficiency really is the most important—say, the cops are coming right at you and you have to decide what to do. Or when there are a lot of working people who just don’t have the time for long meetings. Or when you’re working with allies with very different traditions. A lot of people-of-color groups are very suspicious of consensus. They see it as a white granola crunchy sort of thing, and in a situation like that, it would be really arrogant to insist it’s the only way to go.

Mac: And there are situations when consensus just won’t work. When we were organizing homeless people in Toronto, we tried and tried. Meetings took forever, everybody stood up and made speeches, no one would respect the stack but they’d interrupt and argue with each other…

George: [Laughs.] Sounds like a bunch of aging Marxists.

Megan: Or, actually, most anarchists who are over forty or fifty years old.

Sara: Oh, god, I was at the Brecht Forum at a meeting of the Libertarian Book Club last week and almost everyone there were older generation anarchists. And I couldn’t believe it: have these guys ever heard of process? Or even basic respect for other human beings? They were all jumping on chairs and cutting each other off, and at one point I swear two of them were literally screaming at each other.

David: Yeah, so now you know why I stayed away from anarchist politics for the first thirty-eight years of my life.

Mac: Anyway, so in Toronto, finally we just gave up and adopted a different process.

Lesley: So how shall I write down your point? “Process versus decision”?

Mac: Yeah, that’s good. Anyway, sorry, I’ve been hogging the floor. Anyone else?

Chris: Well, I guess the idea of consensus is that it’s a way of seeking commonality. You start by assuming everyone in the room probably has a somewhat different perspective, and you’re not trying to change that, you’re just trying to see if you can create some sort of common ground.

Neala: Also, it’s supposed to be a process where everyone has an equal opportunity to participate in shaping the final decision. Unlike in majority voting, where you always end up with some alienated minority who voted against the proposal but then they just have to live with it anyway. Everyone has some input, a chance to suggest changes.

[Lesley is scribbling away]

Jessica: Though I think it’s more than that. There have been times I’ve been at meetings and there’s a proposal I didn’t even like all that much, but over the course of the discussion, it became obvious that just about everyone else thought it was a really good idea. I found there’s actually something kind of pleasurable in being able to just let go of that, realizing that what I think isn’t even necessarily all that important, because I really respect these people, and trust them. It can actually feel good. But, of course, it only feels good because I know it was my decision, that I could have blocked the proposal if I’d really wanted to. I chose not to take myself too seriously.

Lesley: So how would I write that down?

Jessica: Maybe… well, “egoism.” “Consensus disempowers egoism.” Something like that.

Mac: Great. What else?

Nat: For me, the nice thing about consensus is that everyone has their brain turned on. I don’t just go to sleep like I used to in most of the meetings I’ve ever been to because what I think actually can have some bearing on what’s happening, at any point.

Sara: Plus you have to actually listen to what other people say.

David: Actually, that’s one of the things I really like about consensus process. In majoritarian politics, you’re always trying to make your opponent’s idea look like a bad idea, so the incentive is always to make their arguments seem stupider than they really are. In consensus, you’re trying to come up with a compromise, or synthesis, so the incentive is to always look for the best or smartest part of other people’s arguments.

Chris: I’d write “creativity.” Some of the most beautiful examples of consensus I’ve ever seen have been when everyone seems at loggerheads, you have two different proposals and there seems no possible way to reconcile them, it’s starting to look like the group’s divided 50/50 and everyone’s starting to dig in their heels, and then, suddenly, someone just pops out with a completely new idea and everyone instantly is like, “oh, okay. Let’s do that then.”

Mac: Actually that’s a really important point because it’s a common misunderstanding that consensus is mainly about compromise—so then critics will say consensus process means that when you do come to a decision, it always tends to come out kind of wishy-washy. That’s not true. Sometimes it’s about compromise. But it’s also about leaving things maximally open to collective creativity, so sometimes instead of trying to reach a compromise you can just make up a completely new proposal.

Megan: Plus, you can come to decisions as radical as the group making them…

[And so on. At the end we spent a minute or two talking about the challenges and pitfalls, mainly the dangers “consensus by attrition,” when a determined minority tries to wear everyone else out, but most of these had already been laid out in the “ doesn’t work” section.]

HISTORY

Mac: I’ll just do this briefly. Now, of course there are a lot of Native American societies who have been making decisions by consensus for thousands of years. In the United States, though, consensus process really goes back to the Quakers; it only began to be adopted by activist groups with the anti-war and anti-nuclear movement in the 1970s, which a lot of Quakers were involved with. There were sections of the civil rights movement that used consensus—SNCC did, but others, like the Southern Christian Leadership Council, didn’t. SDS, and others active in the ‘60s anti-war movement, also used consensus to some degree.

In the 1970s, feminists really changed and developed the idea—a lot of feminist groups adopted consensus as a kind of antidote to some of the more obnoxious macho leadership styles of the 1960s, and that’s when the kind of consensus process we’re using now really came into being. From there, it was adopted in the anti-nuke campaigns in the 1970s and 1980s, and became widely adopted in the environmental movement, particularly in radical environmental groups like Earth First! It’s from there it really came to DAN.

The labor movement does not use consensus. They use Robert’s Rules of Order. Even though labor solidarity is a big part of DAN. That can create a cultural clash sometimes. Actually, in Police & Prisons we sometimes have the same problems because a lot of the groups we’re working with are organized totally differently.

Nat: So, one thing I’ve always wondered is: do we do things this way because we think it’s the most effective, or is the idea that this is the way things will work in the future, that we’re starting to create our dreams now.

Jim: Well, ideally, it should be a little of both.

Sara: But you say labor hasn’t really embraced consensus. So, have there been any attempts to apply these ideas to organizing workplaces, or anything, I guess, other than planning actions or little co-ops and the like?

Jim: It’s certainly not unknown. The IWW have definitely done some experiments with collectivization, worker-run enterprises that… I’m pretty sure they operated by some kind of consensus process. And actually there are a fair number of nonprofits or even capitalist firms that use some version of consensus in their day-to-day operation. I’ve seen a list somewhere: it’s actually surprisingly long. Everything from the US Forestry Service to Saturn and Harley-Davidson and, of course, almost any large corporation in, say, Japan, operates by some kind of consensus. But examples like that also make it clear there’s consensus and there’s consensus; you do even very egalitarian-seeming process within what’s still a totally hierarchical, top-down organization and the process itself become a form of coercion or oppression, a way of constantly forcing you to pretend to agree with decisions in which you really had no say.

TERMINOLOGY

The basic terms, according to the new sheet on the wall, are:

PROPOSALS

FRIENDLY AMENDMENTS

STAND-ASIDES and BLOCKS

MODIFIED CONSENSUS

Lesley: So, I’ll assume we’re all familiar with the basic structure of a DAN meeting. We generally have two facilitators, one male, one female, and they usually take turns, with, at any time, one of them actually leading discussion, and the other managing the stack of speakers. Keeping stack is actually an important skill, because you don’t want to leave people standing there with their hands up for ten minutes until they get called on. You want to be able to catch their eye, nod, or send some kind of little signal that they’re on the stack, and then keep track of the order, even if you don’t necessarily know who they are—so you might have to call on “the woman with the green shirt,” or “the man in red in the front.” In which case it’s important to be consistent. I always use shirt color if I can’t remember the name. Obviously you’re not going to be calling on “the fat chick in the front,” or “the guy with the gigantic nose ring,” but you’d be amazed how almost anything you single out about someone might have a subtle effect of making them feel alienated or… well, singled out. So keep it uniform.

So anyway: proposals. A proposal is a suggestion as to a course of action that someone’s putting before the group. Proposals can be presented by an individual or by a group—in DAN, the usual idea is that important proposals are brought to DAN General by representatives of one of the working groups. But it doesn’t have to be, anyone can actually propose something.

Sara: Does a proposal have to be written down?

Lesley: No. We ask working groups to bring theirs in writing, but half the time they don’t remember, and individuals’ proposals are almost never written out.

Someone: Does a proposal have to refer to a course of action?

Lesley: Actually, that’s a good question. Does it? Well, I guess it depends on how you define the term. For example, when you first put a group together, you have to come to consensus around your principles of unity. Or you can consense on, say, endorsing someone else’s action, or on the text of some outreach literature. But, generally speaking, it’s something you want to do. The one thing you definitely don’t use consensus for is for questions of definition: like should US intervention in Somalia be considered an example of imperialism or something like that. You’re not trying to define reality. You’re trying to decide what to do.

David: So you’ll never get in a situation like in the ISO—or, I think it was their British branch, the SWP—where I heard that all the anthropologists were purged recently because they didn’t agree with the party line that humans had only really become human in the Neolithic. (I don’t know if this is really true.)

Mac: Yeah, the whole idea is to make sure that kind of crazy shit never happens. Insofar as we even talk about such questions—like “are we an anti-capitalist organization?”, “are we opposed to all forms of hierarchy?”—it’s going to be in the mission statement, or principles of unity. And those are important because they’re the basis on which you block. But, we also try to keep those limited to points which will have some bearing on action.

Lesley: So, generally speaking, a proposal is a suggestion for action put before a group. As facilitator, the first thing you do when someone has made a proposal is ask for clarifying questions: to make sure everyone is clear on exactly what’s being proposed. Then you ask if anyone has any concerns: problems such a course of action might cause, reasons why it might not be the best course of action to take. (As facilitator, you’ll find it’s sometimes a little tricky distinguishing clarifying questions from concerns.) Sometimes, at this point, it becomes obvious there’s a strong feeling against the proposal, and the person who presented it might just decide to withdraw it. Alternately, people might propose one or more friendly amendments, to address the concerns, which—if the person making the proposal accepts them—then become part of the proposal.

Jim: It’s good to have a scribe for this—someone writing everything down for when you have to restate the proposal in its current form.

Lesley: Or someone might decide instead to put out an alternative proposal. Or you might end up with a whole bunch of them. Though it tends to get real messy if you get past two or three.

Mac: There are techniques for getting rid of annoying proposals that no one really likes. For instance, in Police & Prisons, we’ll sometimes say “maybe we should form a working group to discuss that,” and pass around a sign-up sheet for the working group. And then, of course, no one signs up.

Lesley: But this is the main role of the facilitator: to walk the group through, clarify what the proposals are, what problems or issues folks might have with them, whether anything needs to be added, or modified. It can get really tricky if there’s more than one proposal on the table. There are a series of tools you can use in that case. You can have a verbal go-round, and ask everyone to weigh in on the question. Or you can try a non-binding straw poll: a show of hands. That’s not the same as a vote, because it’s not actually a way of coming to a decision, but it can give you a sense of the room and, often, if you discover one proposal has very strong support and the second, almost none, that’s really all you need to know. Or you can go over each in turn “does anyone still have serious concerns with proposal #1?”

Jim: Bear in mind here that proposals are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Lesley: Yes, the one thing you always want to encourage people to do is to break down dichotomies, point out the ways people are all saying the same thing. Even in very practical things, it’s the job of the facilitator to try to define the common ground: “So I’m hearing a very strong feeling that we shouldn’t do anything that’s very militant until Tuesday, and also a lot of concerns that we not endanger the surrounding community. Now, is there anyone who feels we shouldn’t do a militant action at all, even on Tuesday?”…

Jim: Or it can go the other way. If you keep restating the proposals, you can sometimes discover that people are actually interpreting words differently, and there really are very different ideas as to what’s going on.

Lesley: Finally, hopefully, you’ve boiled things down to one proposal and you’re up to the point of actually trying to find consensus. At that point, you ask if there are any stand-asides, or any blocks. Now, in the case of a stand-aside, there’s actually different interpretations of what that means. One is that you’re in effect saying “I won’t participate in this action myself, but I have no problem with the rest of the group doing it.” Another is that you’re against the idea, but you don’t feel it’s so serious a problem you’d actually leave the group over the issue. It’s a way to register a minor objection, and it’s important that after you do come to consensus, you give everyone who stood aside a chance to explain why they objected, and to have them registered in the meeting notes if they want them to be.

If there are a lot of stand-asides, say, five or six in a group of twenty, then that’s a serious problem. It means the process broke down at some point, because those people should have had the chance to voice their objections before it came to that.

As for blocks, it’s a really nice thing to know that you can block a proposal, that if you feel that strongly about something you could stop a proposal dead in its tracks, but it’s basically a safeguard. If you do it, things can get ugly. Because you’re basically saying, “this violates the fundamental principles of the organization and I can’t allow it.”

Mac: Of course it’s also totally critical because without the power to block, it’s not consensus. That’s why we’ve tried to get some kind of mechanism for blocking into Continental DAN, even though it’s hard to figure out how you’d do it in a large federative structure.

Lesley: It’s not to be done lightly. Usually, if you block, you run the danger of isolating yourself, people will often be tempted to badger a blocker—so it’s important to bear that in mind as facilitator and make sure the person is being respected.

Jim: One person I once saw—this was like a facilitator’s worst nightmare—it was at an anarchist convention, and there was this one guy who just blocked everything because he was against consensus on principle. I’m never quite sure what, had I been facilitator, I would be able to do about that. [He looks to Mac.]

Mac: Well, a block is supposed to be based in the founding principles or reasons for being of the group, so I’d say you could challenge it on that basis. If the group is based on consensus, it’s hard to see how blocking because you don’t like consensus could be consistent with that. That would be the very definition of an unprincipled block.

Jim: Yes, but then, isn’t it also a basic principle of consensus decision-making that you can’t challenge another activists’ motives? You have to give them the benefit of the doubt for integrity and good intentions. So how do you challenge them on that?

Mac: Well, when you say “unprincipled block,” I think that means not rooted in the group’s principles of unity. You’re not saying that the person is personally unprincipled. Sounds like you’re dealing with a person who’s being totally honest and principled about his motives, they’re just not the principles of the group. Which kind of raises the question of why he came to their meeting in the first place. I’d tell him: why not join a group whose principles he likes, or if that doesn’t exist, try to start a new one?

Christa: But I thought the idea of a block is that you’re saying “this is an issue so important to me I’d be willing to quit the group over it”? Not necessarily a matter of founding principles.

Mac: Well, it doesn’t have to be, though it’s true some interpret it that way.

Chris: At A16, in my affinity group, we had a proposal to build a roadblock out of materials from a nearby construction site, and someone blocked it because they thought we didn’t have the right to carry off stuff that didn’t belong to us and that didn’t have anything to do with the IMF or World Bank. But our affinity group didn’t actually have any formal principles of unity. So how would that be justified?

Lesley: Well, usually the idea is, either you’re saying a proposal violates your founding principles, or that it violates the basic reasons for being or purposes of the group. So there’s wiggle room. But generally speaking, you don’t want to be super-legalistic about this kind of thing. Or maybe it’s better to say, if people start getting super-legalistic, then that’s usually a sign you have a real problem in the group.

Megan: At one point, at A16, we were outside the jail—there were about sixty of us outside doing jail solidarity. We had expected that our lawyers would be allowed in to see the arrestees, but the cops turned them all away. Some of us wanted to put on a really loud and defiant protest. There was a crew with puppets and drums who were really into the idea of having a big parade around the jail. But someone pointed out that it wasn’t just activists who were being held in there, that there were families of other inmates who also wanted to get in. We’d formed a circle and were trying to decide what to do. If we raised a ruckus, let alone tried a lockdown, then all those others wouldn’t be able to get inside. Someone blocked against anything that would make so much noise it would make problems for other visitors. So some of the puppet folks announced, “We have no consensus, here, so we’re going to start a new affinity group for people who still want to have a parade.”

Mac: Well, yeah, you can have some, um, creative solutions to that sort of impasse.

Christa: So did they have the parade?

Megan: Actually, I’m not sure what happened. It was around then that I left. I think they had a parade, but it was much more low-key than they’d originally intended. What’s more, I think a lot of the problem was that the blocker was a newcomer, most people didn’t know her, which complicated things.

Lesley: Actually, that’s another thing facilitators have to figure out ways to deal with—because if there’s a new person, if you don’t, often they won’t be taken as seriously.

Sara: Can it ever come down to openly questioning the motivations of the blocker? Like, you don’t actually know if that woman wasn’t a cop.

Mac: Well, I suppose in that case you could, but I would be really careful about publicly suggesting someone might be a cop.

Lesley: Actually, I’d say no. You can’t question a person’s motivations. That’s a matter of basic principle. But you can question their reasoning. Or, as facilitator, you can try to reframe things, ask the person, “Well, what would you need in order to feel comfortable with the proposal?” That’s if you’re pretty sure someone is prepared to block. And, if they actually do block, then sometimes it’s a good idea to suggest that the blocker join the working group that originally brought the proposal, or, anyway, work with whoever it was to see if they can’t come up with some kind of alternative they’d be willing to live with.

Which actually leads to another concept, modified consensus. DAN itself hasn’t actually decided if it has an option to fall back on this, but…

Neala: Wait a minute: I thought it had.

Mac: Well, yeah, technically, I think it’s in our principles, but we’ve never actually defined what that would mean in practice.

Lesley: Modified consensus would be, for example, if you have just one or two blocks, but others felt it was absolutely critical to force the issue, you might have an option to go to a weighted vote: say, two-thirds majority, or seventy or eighty percent Sometimes, you won’t even be able get that kind of majority, because the fact that one person felt strongly enough to block will be enough to convince a lot of other people to change their minds and vote against the proposal. Anyway, there are other forms of modified consensus: for example, consensus minus one, where if someone blocks, you go around to see if there’s at least one other member of the group who feels their argument is compelling enough that they’d back it up. Some groups use consensus minus two or three, and so on. Anyway, the critical thing here is this is a last resort; you only fall back on it if you’ve done everything possible to get consensus and you just can’t. I’ve been involved in a lot of groups with a modified consensus option, but not one where we actually had to use it—which I’m very happy to be able to say, because the whole idea makes me really uncomfortable. No one has ever been able to explain to me how the whole idea really squares with the principle of consensus.

Jim: The groups that really tend to use modified consensus the most are very large groups, like spokescouncils, where people don’t really know each other, and sometimes you just don’t have time to allow any one person to hijack the process.

George: Wasn’t there supposed to be a case of one DAN chapter on the West Coast where some ISO people wanted to show how consensus couldn’t really work, so they just blocked everything? Sort of like Jim was talking about at the anarchist convention.

Jim: Oh. I hadn’t heard about that.

Mac: [sighs] Yeah, that was San Francisco DAN. It almost destroyed the group. There were only three ISOers, but they tried to systematically sabotage the process to force people to go over to majority vote.

David: What did they end up doing?

Mac: Well, one day, there was a meeting where the ISO people didn’t show up, so everyone immediately put through a proposal that the group would operate on consensus minus three.

TOOLS AND RULES

Jim: So we thought we’d end with some tools and resources for facilitators, which you may or may not want to use. The first of these is a timekeeper. That’s important because, in making the agenda, you definitely want to have people agree on how much time you want to allocate to each item, but there’s no point in doing that unless someone’s paying attention and is able to tell everyone that time for discussion is over and someone will have to propose an extension if we’re going to go on. I like to keep my own time, but some use a timekeeper, or have the co-facilitator do it.

Then there’s the scribe, which I think is really important. Especially if it’s before a big action and there’s huge amounts of information to keep track of, and you can’t assume that everyone in the room is taking notes. In the past, I often forgot to make sure there was a minute-taker, and sometimes it really came back to haunt me because people would have different memories about what we actually decided. In big formal DAN meetings, you want to make sure at the very least there’s someone writing down all the proposals, precisely what’s been consensed on, with all the friendly amendments and so on. It’s also useful to keep a permanent record of important decisions in some place that’s publicly available, like a web page, because that becomes like the institutional memory of the group. If you don’t, it can become the basis for a tacit power structure, because some people have immediate access to that information just because they’ve been around for a long time, or keep track of it—they can suddenly interrupt a discussion and say, “but wait a minute! we already decided that a year ago”—and other people just don’t know. One of the key things you’ll find in an egalitarian group is that access to information becomes the main basis for emerging power structures, so you have to do everything possible to try to nip that sort of thing in the bud.

What else?

Water. Having a small bottle of water next to you in a meeting is really helpful. That’s not just for facilitators—everyone should have access to water. If you find your throat is so dry you’re constantly reaching for the water, then that’s a good sign you’re talking too much and should shut up.

Lesley: Food, too. It’s not a bad idea to have some kind of food in the back of the room, especially if the meeting is likely to go on for hours. And you should pay attention to make sure there aren’t other factors that might be keeping some people from attending your meetings: lack of childcare, for example, or translators.

Mac: We’ve already talked about straw polls. If you have various proposals on the floor, it’s a useful technique to gauge people’s feelings. Also, if it’s something which couldn’t possibly turn on a matter of principle, like, should we have the next meeting on Tuesday or on Wednesday, sometimes a straw poll is all you need. Um, what else?

Jessica: What about hand signals? At the coop I was part of in Oberlin, we had a whole series of hand signals: the facilitator could ask for people’s feelings towards a proposal and you could either give a thumbs up, thumbs down, or thumbs sideways if you were undecided.

Mac: Everybody uses different ones. In DAN of course we twinkle, you know, waving your fingers in the air to express strong support or approval for a proposal or someone else’s point—though a few people find the whole idea of “twinkling” kind of a flaky California thing.

Jessica: At Oberlin we’d do “knocking,” you make a fist and gesture like this.

Mac: There’s a million of them. Some people use little devil fingers—you know, like you’d put behind someone’s head in a photograph if you’re six years old and think that sort of thing is really clever?

Lesley: But there’s a few standard ones that are kind of useful. A lot of groups use a gesture for “direct response”: if someone makes a point and you have factual information that bears directly on it, but very directly, like, “no, they cancelled that event,” or one speaker is actually asking you a question and you want to reply. You have to be very careful with that one. Because you really don’t want things to descend into cross-talk, which means then you can end up with some kind of ego contest between two people and everyone else is annoyed and shut out. It’s usually better to keep to the stack, and let the conversation end up being a little frustratingly circuitous, than giving people an excuse to be all self-important and dominate the conversation. There’s also the little triangle you make with your fingertips that means “point of process”—that’s another way to cut into the stack, but that’s just for comments you’re making directly to the facilitator, for example, “aren’t we supposed to still be discussing the other proposal?” or “didn’t we already decide this last week?”

Christa: I have a question about go-rounds. Do you find them effective? And when do you use them?

Lesley: You have to be careful with go-rounds. It’s a nice way to encourage people who might be too shy or unsure of themselves to speak to offer an opinion, but they take a lot of time. You definitely have to set time limits. Even if you allow, say, one minute per speaker, if there’s sixty people in the room, that’s an hour right there. So they’re best with small groups. On the other hand, if it is a small group, and it’s very important, you can even try two go-arounds, to see if people’s ideas evolve when they hear what other people have to say. If it’s a big group it’s better to fall back on the old “let’s just hear from people who haven’t spoken so far” trick. That last one is useful because, say, if white men are completely dominating the conversation and none of the women or people of color are talking, you can point that out, it sounds a bit patronizing to say “let’s hear from some women for a change.” Or, “let’s hear from some African-Americans.” But asking for people who haven’t already spoken can have pretty much the same effect.

George: What about the whole “hearing” thing?

Lesley: Huh?

George: You know, when the facilitator says, “I’m hearing a lot energy around the idea of such and such.”

Lesley: Well, usually that’s a way of trying to catch the sense of the room, to suggest there’s some sort of emerging consensus on the part of the group, at least around certain aspects of a proposal. Of course, it’s only a suggestion. In part, it’s a way of testing, because sometimes, if you say, oh, I don’t know, “I’m hearing a lot of support for the idea of a parade of some sort” then someone will immediately say “No, actually, I don’t think there should be any kind of parade at all.”

Jim: We’re kind of running out of time here so let me just throw out a couple other techniques very quickly. Some of these are things which, well, on the West Coast they often have a vibes-watcher, whose job is to keep track of the emotional quality of the room. If people are getting bored, or tense, or angry, or someone is feeling alienated or excluded, or, for that matter, if it’s too hot or there’s not enough light, they step in and intervene. Here, it’s usually the facilitator who has to keep track of these things, which can make things really difficult because you’re juggling so many other responsibilities at the same time. The most important thing, though, is to be able to intervene if things are starting to get too tense and confrontational. Often, if you just call a time-out, let people stand up, stretch, let folks go out and smoke a cigarette or get water if they want to, when they come back, the entire mood is usually different and what seemed like major problems beforehand just look silly or unimportant. Some facilitators even suggest yoga, or breathing exercises.

Lesley: Or one big favorite is group back rubs.

Mac: And then there’s the whole idea of the reconciliation committee. If there’s a block, sometimes, you might call a time-out and use the occasion to talk to the principals, the person making the proposal and the person who blocked, and maybe one or two other people you know they both trust, and see if you can’t get them to step out of the room together to talk the whole thing through and then come back to the meeting with a new proposal.

Neala: You know, I wouldn’t object to a little stretching break right now.

Which we did. This was followed by a role-play, where we used what I later learned is the classic, no-frills role-play for consensus trainings where you don’t have that much time: twelve people ordering a pizza. If you have time, you can add all sorts of complications: various participants are secretly handed scraps of paper informing them they are passionately fond of anchovies, they’re vegans, and so on. The task is to see if the person named facilitator can overcome these difficulties in a fairly short period of time—in this case, two minutes, which was slightly ridiculous.

In the trainings I’ve attended since—most of which I played some part in helping to organize, though I was never the main organizer—the role-plays took up more and more time and became more and more elaborate. In one, eight people with different political views—doctrinaire Marxists, militant anarchists, reformist environmentalists—but only one banner, were to come up with a slogan to write on it (I think we ended up with “Burn Banks, Not Trees”); later, we had an exercise in which we were trying to march into a besieged church in Bethlehem and were told to disperse by heavily armed Israeli soldiers, a situation one of the organizers had recently experienced (the most effective approach, we discovered, was to send one small group to negotiate while the rest tried to slip through another way). The most interesting, perhaps, was at a different training, where twenty activists took on the role of IMC journalists in the middle of a major action. One of them had just come in with a videotape she’d shot of the chief of police murdering an activist in cold blood; there was only one copy; the building was surrounded and the police beginning to move in. That one was meant to illustrate the limits of consensus.

Jim took some time to explain the importance of keeping one’s cool as facilitator; to get oneself calm and centered beforehand. “I always take a half hour beforehand when I don’t think about anything, just relax. A walk on the beach or in the park would be ideal if that’s possible.” Then we moved into how a DAN meeting was actually structured, with the help of a recently completed structure sheet, in indelible ink, with laminated sheets on top so that facilitators could write the particulars on top of it in magic marker and wipe it away for the next meeting.

Mac explained that at the last DAN meeting, we finally consensed on a basic skeleton structure for meetings, which runs something like this:

ORIENTATION (This usually lasts ten to fifteen minutes, as people file in late. This is where we do icebreakers, usually a listening exercise, talk about the goals of the meeting,)

INTRODUCTIONS (Everyone goes around in a circle and says who they are, what other projects or working groups they might be active in)

AGENDA REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS (Where people can add items to the agenda)

EMERGENCY EVENT ANNOUNCEMENTS (No more than ten minutes)

WORKING GROUP REPORT-BACKS (Ten minutes; this is where you pass around sign-up sheets for your working group, or for projects or events)

ONGOING BUSINESS

A) Proposals brought forward from internal working groups (Ten minutes each)

B) New Business (Sixty minutes max total)

C) Group Education (We’ve never actually done this yet, but if we have something like a video to show, an outside speaker)

7. DISCUSSION NEXT MEETING (Name the new facilitator, etc.)

8. FINAL ANNOUNCEMENTS

After some minor discussion (remember to get people with announcements to specify how much time they’re going to take; if working group report-backs start to turn into long discussions, cut it off and shove it all into New Business, etc):

Jim: Being a facilitator can be extremely trying, and frustrating. It may seem like you’re trying to drag people along against their will. But you always have to remember, it’s not an adversarial relation. If you’re the facilitator, the group is your ally. They want you to succeed.

Lesley: It’s better if you let the group itself set the agenda and, especially, decide how much time to allocate for different items. The more you do so, the more they won’t mind when if you say “Okay, time is up.”

Different groups demand different styles of facilitation. If people are too passive, mellow, and agreeable, then you have to become more of a leader. Otherwise, everyone might end up passively assenting to decisions they’ll all complain about later, and start feeling like someone put something over on them. So, in cases like that, you have to make sure half the people in the room aren’t secretly swallowing their objections. Try to coax them out. Also, for larger groups, you often need a more hands-on, take-charge approach—a stronger style of facilitation.

You’ll often hear, in fact, certain activists referred to as “strong facilitators” in that sense; ones capable of aggressive intervention, especially in large groups. It’s considered an essentially admirable quality. In my experience, interestingly, strong facilitators are almost invariably women. In part, this is probably because men who behave this way very quickly tend to get on someone’s nerves. But it is also common wisdom that most of the best facilitators are women.

Awesome summary of a really important topic... both by you, Crow, and the Graeber piece you selected. Based on my own experience with Quakers and secular groups using consensus, I would add just a couple of points of clarification.

You write, "[Consensus] can’t be summoned into being overnight amongst a loose collection of people who barely know each other."

Actually I have seen it work with direct action campaigns with such ad hoc groups. And heard from a well-known Quaker/activist who told of success with a group of 500 people at some events she facilitated. But in such cases having such a skilled facilitator definitely is key.

The other comment of yours I would quibble with is "I’m not as hardcore as the Quakers are, by the way. To me, consensus does not mean reaching decisions that everyone loves. It is about reaching decisions that everyone can live with."

I would say what you describe precisely is the mindset of Quakers in their "meetings for business," since it is the practical hinge upon which agreement is possible. Granted, you rightly imply that a basis of unity, however it is understood, is a crucial starting point and underlying principle of consensus. In the Quakers' case, that is a spiritual component, so that even those "business" decisions come in what is called "Meeting for Worship for Business" to reinforce that point (with "worship" or respect of the divine spirit being common to both the above and the mostly silent "Meeting for Worship").

Lacking that organic and palpable sense of togetherness and respect, any group of humans is going to be more challenged to identify and articulate just what their basis of unity is. Though I would argue, the principle of innate human divinity and respect might be achievable even without the "religious" tradition of Quakers to cloak it in. Indeed, that's another way of looking at the whole reason for doing consensus in the first place.

Anarchism and counter-cultural communities only work if there is a frame work of spiritually based ethics to live by.