OCCUPY'S FATAL FLAW

Why Occupy didn't make demands, and why that was a mistake

The entire Occupy Movement began with a single meme. Amazing, I know, but it really is so.

According to Wikipedia:

The original protest was called for by Kalle Lasn, Micah White and others of Adbusters, a Canadian anti-consumerist publication, who conceived of a September 17 occupation in Lower Manhattan. The first such proposal appeared on the Adbusters website on February 2, 2011, under the title "A Million Man March on Wall Street."[10]

[…]

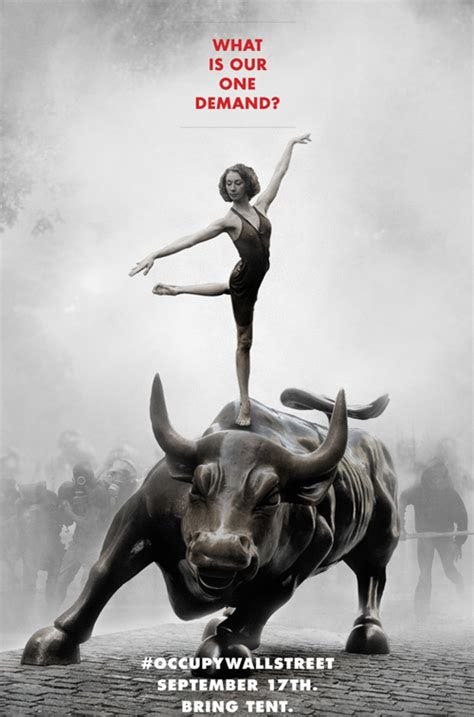

Adbusters proposed a peaceful occupation of Wall Street to protest corporate influence on democracy, the lack of legal consequences for those who brought about the global crisis of monetary insolvency, and an increasing disparity in wealth.[14] The protest was promoted with an image featuring a dancer atop Wall Street's iconic Charging Bull statue.[15][16][17]

This is that image:

In a previous post, I wrote about how Adbusters didn’t actually plan the famous occupation of Zuccotti Park. They just put the idea out there and left the rest to fate.

Let’s let that be a lesson. Fortune favours the bold.

David Graeber, who was a native New Yorker as well as a contributor to Adbusters, answered the call in a truly legendary way.

It’s truly inspiring. A single meme started a massive social movement. I guess it’s true what they say - There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

The Ballerina-on-a-Bull image will surely go down in the history of graphic design, and I think it’s worth thinking about what exactly about this one particular meme that struck such a chord.

Let’s take another look at it.

I could wax poetic about this striking image from a critic’s perspective, but I’m not going to. What I want to focus on is the question: “What is our one demand?”

It’s an intriguing question, isn’t it? It begs the question: Who are we?

The meme does not ask “What is your one demand?”, which would be easier for any one of us to answer. It asks “What is our one demand?”, directing our imaginations outside of our individual desires and into some kind of Collective Wish.

David Graeber answered the “Who are We?” question for us: We are the 99%, which is to say everyone who does nots benefit from wealth being funnelled towards the ultra-rich. Most everyone seemed to agree with this sentiment, which meant that Occupy had, from the beginning, set itself up to be a populist movement.

One then immediately runs into problems, because there is no one political ideology that can claim to represent 99% of humanity, or even just Americans. Any demand that could made in the name of the 99% would necessarily have to be a compromise. Most people are not anarchists. Nor are most people opposed to capitalism. For those with very definite ideas about what kind of political system should replace the global criminocracy that Wall Street represents, a demand to regulate the banking sector might well feel less than inspiring. Therefore, it was decided that Occupy Wall Street would begin with a type of People’s Parliament in which ideas would be discussed. Fair enough.

There were a number of proposals that had broad popular support:

Reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act (i.e. Regulate Banks)

End the Fed

End Corporate Personhood

Get money out of politics

Bail out homeowners saddled with bad mortgages due to predatory lending practices and out-of-control speculation

Cancel Student Debt

All of these would have been quite radical demands within the context of American politics, where cutthroat capitalism is often seen as part of a package that includes democracy, freedom, baseball, Mom’s apple pie, and the American way.

Unfortunately, it proved impossible to reach consensus on any of these proposed demands, and anarchists began opposing making demands on a principle.

I don’t know where this principle came from, and I think that it was misguided, to say the least. David Graeber promoted this idea, as did the Crimethinc Ex-Workers Collective. Soon, anarchists everywhere were opposed to the idea of making demands. Given how central anarchists were to Occupy, this made consensus on any demand impossible. If you ask me, this was Occupy’s fatal flaw.

The argument went something like this - by making demands, the movement would have been acknowledging the power of the state, thereby legitimizing it.

Personally, I don’t think this idea holds water. Anarchists seemed to be confusing demands with requests. There is nothing disempowering about making demands. People tend not to make demands unless they feel that they already have power.

This is one of the times when I disagree with David Graeber, but in today’s post I will nevertheless share his thoughts on why it was the right move for Occupy not to make demands. Even when I don’t agree with David Graeber, I always find his views well worth thinking about. But I do wonder whether his opposition to demands came as some kind of post-hoc rationalization, because his views on the subject of demands seem contradictory. On one hand, he says that making demands of those in power legitimizes their power, but shortly thereafter states that a demand to get money out of politics would be a revolutionary act. Which is it?

If anarchists had been thinking one or two moves ahead, they would have agreed to a demand which had broad popular appeal, but which was impossible for the state to grant. All the above demands, with the possible exception of regulating the banking sector, fell into this category.

Personally, I think that getting money out of politics, by which Occupiers meant ending the system of legalized bribery that dignifies itself under the term “corporate lobbying”, would have been a great idea. I also think the idea of ending fractional reserve banking or corporate personhood would have been absolutely revolutionary demands.

My preference, however, would have been for debt amnesty for students. It makes sense - if banks got bailed out, then why shouldn’t students? And that would have garnered wide support from educated young people, who are always a key demographic in revolutionary movements. And if that morphed from a call from debt amnesty for students to calls for a Biblical Jubilee, so much the better. That’s my revolutionary program - cancel all debts.

I wish that anarchists would have remembered the famous slogan of the Paris 1968 student revolt:

Be realistic - Demand the Impossible.

Love & Solidarity,

Crow Qu’appelle

P.S. I believe I was one of those anarchists who opposed making demands at the time, though I don’t actually remember. I changed my mind after watching this excellent video by What is Politics?, the best political YouTube channel I know of.

If I changed my mind, so can you!

WHY OCCUPY DIDN’T MAKE DEMANDS

By David Graeber, excerpted from The Democracy Project

Why did the movement refuse to make demands of or engage with the existing political system?

And why did that refusal make the movement more compelling rather than less?

One would imagine that people in such a state of desperation would wish for some immediate, pragmatic solution to their dilemmas. Which makes it all the more striking that they were drawn to a movement that refused to appeal directly to existing political institutions at all.

Certainly this came as a great surprise to members of the corporate media, so much so that most refused to acknowledge what was happening right before their eyes. From the original, execrable, Ginia Bellafante piece in the Times, there has been an endless drumbeat coming from media of all sorts accusing the movement of a lack of seriousness, owing to its refusal to issue a concrete set of demands. Almost every time I’m interviewed by a mainstream journalist about Occupy Wall Street I get some variation of the same lecture:

How are you going to get anywhere if you refuse to create a leadership structure or make a practical list of demands? And what’s with all this anarchist nonsense —the consensus, the sparkly fingers? Don’t you realize all this radical language is going to alienate people? You’re never going to be able to reach regular, mainstream Americans with this sort of thing!

Asking why OWS refuses to create a leadership structure, and asking why we don’t come up with concrete policy statements, is of course two ways of asking the same thing: Why don’t we engage with the existing political structure so as to ultimately become a part of it?

If one were compiling a scrapbook of worst advice ever given, this sort of thing might well merit an honorable place. Since the financial crash of 2008, there have been endless attempts to kick off a national movement against the depredations of America’s financial elites taking the approach such journalists recommended. All failed. Most failed miserably. It was only when a movement appeared that resolutely refused to take the traditional path, that rejected the existing political order entirely as inherently corrupt, that called for the complete reinvention of American democracy, that occupations immediately began to blossom across the country. Clearly, the movement did not succeed despite the anarchist element. It succeeded because of it.

For “small-a” anarchists such as myself —that is, the sort willing to work in broad coalitions as long as they work on horizontal principles— this is what we’d always dreamed of. For decades, the anarchist movement had been putting much of our creative energy into developing forms of egalitarian political process that actually work; forms of direct democracy that actually could operate within self-governing communities outside of any state. The whole project was based in a kind of faith that freedom is contagious. We all knew it was practically impossible to convince the average American that a truly democratic society was possible through rhetoric. But it was possible to show them. The experience of watching a group of a thousand, or two thousand, people making collective decisions without a leadership structure, motivated only by principle and solidarity, can change one’s most fundamental assumptions about what politics, or for that matter, human life, could actually be like. Back in the days of the Global Justice Movement we thought that if we exposed enough people, around the world, to these new forms of direct democracy, and traditions of direct action, that a new, global, democratic culture would begin to emerge. But as noted above, we never really broke out of the activist ghetto; most Americans never even knew that direct democracy was so central to our identity, distracted as they were by media images of young men in balaclavas breaking plate glass windows, and the endless insistence of reporters that the whole argument was about the merits of something they insisted on calling “free trade”. By the time of the antiwar movements after 2003, which mobilized hundreds of thousands, activism in America had fallen back on the old-fashioned vertical politics of top-down coalitions, charismatic leaders, and marching around with signs. Many of us diehards kept the faith. After all, we had dedicated our lives to the principle that something like this would eventually happen. But we had also, in a certain way, failed to notice that we’d stop really believing that we could actually win.

And then it happened. The last time I went to Zuccotti Park, before the eviction, and watched a sprawling, diverse group that ranged from middle-aged construction workers to young artists using all our old hand signals in mass meetings, my old friend Priya, the tree sitter and eco-anarchist now established in the park as a video documentarian, admitted to me, “Every few hours I do have to pinch myself to make sure it isn’t all a dream”.

So this is the ultimate question: not just why an anti —Wall Street movement finally took off— to be honest, for the first few years after the 2008 collapse, many had been scratching their heads over why one hadn’t —but why it took the form it did? Again, there are obvious answers. Once thing that unites almost everyone in America who is not part of the political class, whether right or left, is a revulsion of politicians. “Washington” in particular is perceived to be an alien bubble of power and influence, fundamentally corrupt. Since 2008, the fact that Washington exists to serve the purposes of Wall Street has become almost impossible to ignore. Still, this does not explain why so many were drawn to a movement that comprehensively rejected existing political institutions of any sort.

I think the answer is once again generational. The refrain of the earliest occupiers at Zuccotti Park when it came to their financial, educational, and work lives was: “I played by the rules. I did exactly what everyone told me I was supposed to do. And look where that got me!” Exactly the same could be said of these young people’s experience of politics.

For most Americans in their early twenties, their first experience of political engagement came in the elections of 2006 and 2008, when young people turned out in roughly twice the numbers they usually did, and voted overwhelmingly for the Democrats. As a candidate, Barack Obama ran a campaign carefully designed to appeal to progressive youth, with spectacular results. It’s hard to remember that Obama not only ran as a candidate of “Change”, but used language that drew liberally from that of radical social movements (“Yes we can!” was adapted from César Chávez’s United Farm Workers movement, “Be the change!” is a phrase often attributed to Gandhi), and that as a former community organizer, and member of the left-wing New Party, he was one of the few candidates in recent memory who could be said to have emerged from a social movement background rather than from the usual smoke-filled rooms. What’s more, he organized his grassroots campaign much like a social movement; young volunteers were encouraged not just to phone-bank and go door-to-door but to create enduring organizations that would continue to work for progressive causes —support strikes, create food banks, organize local environmental campaigns— long after the election. All this, combined with the fact that Obama was to be the first African-American president, gave young people a sense that they were participating in a genuinely transformative moment in American politics.

No doubt most of the young people who worked for, or supported, the Obama campaign were uncertain just how transformative all this would be. But most were ready for genuinely profound changes in the very structure of American democracy. Remember that all this was happening in a country where there is such a straitjacket on acceptable political discourse —what a politician or media pundit can say without being written off as a member of the lunatic fringe— that the views of very large segments of the American public simply are never voiced at all. To give a sense of how radical is the disconnect between acceptable opinion, and the actual feelings of American voters, consider a pair of polls conducted by Rasmussen, the first in December 2008, right after Obama was elected, the second in April 2011. A broad sampling of Americans was asked which economic system they preferred: capitalism or socialism? In 2008, 15 percent felt the United States would be better off adopting a socialist system; three years later, the number had gone up, to one in five. Even more striking was the breakdown by age: the younger the respondent, the more likely they were to object to the idea of spending the rest of their lives under a capitalist system. Among Americans between fifteen and twenty-five, a plurality did still prefer capitalism: 37 percent, as opposed to 33 percent in favor of socialism. (The remaining 30 percent remained unsure). But think about what this means here. It means that almost two thirds of America’s youth are willing to at least consider the idea of jettisoning the capitalist system entirely! In a country where most have never seen a single politician, TV pundit, or talking head willing to reject capitalism in principle, or to use the term “socialism” as anything but a term of condescension and abuse, this is genuinely extraordinary. Granted, for that very reason, it’s hard to know exactly what young people who say they prefer “socialism” actually think they’re embracing. One has to assume: not an economic system modeled on that of North Korea. What then? Sweden? Canada? It’s impossible to say. But in a way it’s also beside the point. Most Americans might not be sure what socialism is supposed to be, but they do know a great deal about capitalism, and if “socialism” means anything to them, it means “the other thing”, or perhaps better,” something, pretty much anything, really, as long as it isn’t that!” To get a sense of just how extreme matters have become, another poll asked Americans to choose between capitalism and communism —and one out of ten Americans actually stated they would prefer a Soviet-style system to the economic system existing today.

In 2008, young Americans preferred Obama to John McCain by a rate of 68 percent to 30 percent —again, an approximately two-thirds margin.

It seems at the very least reasonable to assume that most young Americans who cast their votes for Obama expected a little more than what they got. They felt they were voting for a transformative figure. Many did clearly expect some kind of fundamental change in the system, even if they weren’t sure what. How, then, might one expect such a young American voter to feel on discovering that they had in fact elected a moderate conservative?

This might seem an extreme statement by the standards of mainstream political discourse but I’m really just using the word “conservative” in the literal sense of the term. That literal sense is now rarely used. Nowadays, in the United States at least, “conservative” has mainly come to be used for “right-wing radical”, whereas its long-standing literal meaning was “someone whose main political imperative is to conserve existing institutions, to protect the status quo”. This is precisely what Obama has turned out to be. Almost all his greatest political efforts have been aimed at preserving some institutional structure under threat: the banking system, the auto industry, even the health insurance industry. Obama’s main argument in calling for health care reform was that the existing system, based on for-profit private insurers, was not economically viable over the long term, and that some kind of change was going to be necessary. What was his solution? Instead of pushing a genuinely radical —or even liberal— restructuring of the system toward fairness and sustainability, he instead revived a Republican model first proposed in the 1990s as the conservative alternative to the Clintons’ universal health plan. That model’s details were hammered out in right-wing think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and initially put into practice by a Republican governor of Massachusetts. Its appeal was essentially conservative: it didn’t solve the problem of how to create a fair and sensible health care system; it solved the problem of how to preserve the existing unfair and unsustainable for-profit system in a form that might allow it to endure for at least another generation.

Considering the state of crisis the U.S. economy was in when Obama took over in 2008, it required perversely heroic efforts to respond to a historic catastrophe by keeping everything more or less exactly as it was. Yet Obama did expend those heroic efforts, and the result was that, in every dimension, the status quo did indeed remain intact. No part of the system was shaken up. There were no bank nationalizations, no breakups of “too big to fail” institutions, no major changes in finance laws, no change in the structure of the auto industry, or of any other industry, no change in labor laws, drug laws, surveillance laws, monetary policy, education policy, transportation policy, energy policy, military policy, or —most crucially of all, despite campaign pledges— the role of money in the political system. In exchange for massive infusions of money from the country’s Treasury to rescue them from ruin, industries from finance to manufacturing to health care were required to make only marginal changes to their practices.

The “progressive community” in the United States is defined by left-leaning voters and activists who believe that working through the Democratic Party is the best way to achieve political change in America. The best way to get a sense of their current state of mind, I find, is to read discussions on the liberal blog Daily Kos. By the third year of Obama’s first term, the level of rage —even hatred— directed against the president on this blog was simply extraordinary. He was regularly accused of being a fraud, a liar, a secret Republican who had intentionally flubbed every opportunity for progressive change presented to him in the name of “bipartisan compromise”. The intensity of the hatred many of these debates revealed might seem surprising, but it makes perfect sense if you consider that these were people passionately committed to the idea it should be possible for progressive policies to be enacted in the United States through electoral means. Obama’s failure to do so would seem to leave one with little choice but to conclude that any such project is impossible. After all, how could there have been a more perfect alignment of the political stars than there was in 2008? That year saw a wave election that left Democrats in control of both houses of Congress, a Democratic president elected on a platform of “Change” coming to power at a moment of economic crisis so profound that radical measures of some sort were unavoidable, and at a time when Republican economic policies were utterly discredited and popular rage against the nation’s financial elites was so intense that most Americans would have supported almost any policy directed against them. Polls at the time indicated that Americans were overwhelmingly in favor of bailing out mortgage holders, but not bailing out “too big to fail” banks, whatever the negative impact on the economy. Obama’s position here was not only the opposite, but actually more conservative than George W. Bush’s: the outgoing Bush administration did agree, under pressure from Democratic representative Barney Frank, to include mortgage write-downs in the TARP program, but only if Obama approved. He chose not to. It’s important to remember this because a mythology has since developed that Obama opened himself up to criticism that he was a radical socialist because he went too far; in fact, the Republican Party was a spent and humiliated force, and only managed to revive itself because the Obama administration refused to provide an ideological alternative and instead adopted most of the Republicans’ economic positions.

Yet no radical change was enacted; Wall Street gained even greater control over the political process, the “progressive” brand was tainted in most voters’ minds by becoming identified with what were inherently conservative, corporate-friendly positions, and since Republicans proved the only party willing to take radical positions of any kind, the political center swung even further to the right. Clearly, if progressive change was not possible through electoral means in 2008, it simply isn’t going to be possible at all. And that is exactly what very large numbers of young Americans appear to have concluded.

The numbers speak for themselves. Where youth turnout in 2008 was three times what it had been four years before, two years after Obama’s election, it had already dropped by 60 percent. It’s not so much that young voters switched sides —those who showed up continued to vote for the Democrats at about the same rate as before— as that they gave up on the process altogether, allowing the largely middle-aged Tea Partiers to dominate the election, and the Obama administration, in reaction, to compliantly swing even further to the right.

So in civic affairs as in economic ones, a generation of young people had every reason to feel they’d done exactly what they were supposed to do according to the rulebook —and got worse than nothing. What Obama had robbed them of was precisely the thing he so famously promised: hope —hope of any meaningful change via institutional means in their lifetimes. If they wanted to see their actual problems addressed, if they wanted to see any sort of democratic transformation in America, it was going to have to be through other means.

But why an explicitly revolutionary movement?

Here we come to the most challenging question of all. It’s clear that one of the main reasons OWS worked was its very radicalism. In fact, one of the most remarkable things about it is that it was not just a popular movement, not even just a radical movement, but a revolutionary movement. It was kicked off by anarchists and revolutionary socialists —and in the earliest meetings, when its basic themes and principles were first being hammered down, the revolutionary socialists were actually the more conservative faction. Mainstream allies regularly try to soft-pedal this background; right-wing commentators often inveigh that “if only” ordinary Americans understood who the originators of OWS were, they would scatter in revulsion. In fact, there is every reason to believe that not only are Americans far more willing to entertain radical solutions, on either side of the political spectrum, than its media and official opinion makers are ever willing to admit, but that it’s precisely OWS’s most revolutionary aspects —its refusal to recognize the legitimacy of the existing political institutions, its willingness to challenge the fundamental premises of our economic system— that is at the heart of its appeal.

Obviously, this raises profound questions of who the “mainstream opinion makers really are” and what the mainstream media is for. In the United States, what is put forth as respectable opinion is largely produced by journalists, particularly TV journalists, newspaper columnists, and popular bloggers working for large platforms like The Atlantic or The Daily Beast, who usually present themselves as amateur sociologists, commenting on the attitudes and feelings of the American public. These pronouncements are often so bizarrely off base that one has to ask oneself what’s really going on. One example that has stuck in my head: after the 2000 George W. Bush-Al Gore election was taken to the courts there was immediate and overwhelming consensus among the punditocracy that “the American people” did not want to see a long drawn-out process, but wanted the matter resolved, one way or another, as quickly as possible. But polls soon appeared revealing that in fact the American people wanted the exact opposite: overwhelming majorities, rather sensibly, wished to know who had really won the election, however long it took to find out. This had virtually no effect on the pundits, who simply switched gears to saying that though what they had declared might not be true yet, it definitely would be soon (especially, of course, if opinion makers like themselves kept incessantly flogging away at it).

These are the same purveyors of conventional wisdom who contorted themselves to misread the elections of 2008 and 2010. In 2008, in the midst of a profound economic crisis, we saw first a collapse of a disillusioned Republican base and the emergence of a wave of young voters expecting radical change from the left. When no such change materialized and the financial crisis continued, the youth and progressive vote collapsed and a movement of angry middle-aged voters demanding even more radical change on the right emerged. The conventional wisdom somehow figured out a way to interpret these serial calls for radical change in the face of a clear crisis as evidence that Americans are vacillating centrists. It is becoming increasingly obvious, in fact, that the role of the media is no longer to tell Americans what they should think, but to convince an increasingly angry and alienated public that their neighbors have not come to the same conclusions. The logic is much like that used to dissuade voters from considering third parties: even if the third-party challenger states opinions shared by the majority of Americans, Americans are constantly warned not to “waste their vote” for the candidate that actually reflects their views because no one else will vote for that candidate. It’s hard to imagine a more obvious case of a self-fulfilling prophecy. The result is a mainstream ideology —a kind of conservative centrism that assumes what’s important is always moderation and the maintenance of the status quo— which almost no one actually holds (except of course the pundits themselves), but which everyone, nonetheless, suspects that everyone else does.

It seems reasonable to ask, How did we get here? How did there come to be such an enormous gap between the way so many Americans actually viewed the world —including a population of young people, most of whom were prepared to contemplate jettisoning the capitalist system entirely— and the opinions that could be expressed in its public forums? Why do the human stories revealed on the We Are the 99% tumblr never seem to make it to the TV, even in (or especially in) “reality” television? How, in a country that claims to be a democracy, did we arrive at a situation where —as the occupiers stressed— the political classes seem unwilling to even talk about the kind of issues and positions ordinary Americans actually held?

To answer the question we need to take a broader historical perspective.

Let’s step back and revisit the question of financialization discussed earlier. The conventional story is that we have moved from a manufacturing-based economy to one whose center of gravity is the provision of financial services. As I’ve already observed, most of these are hardly “services”. Former Fed chairman (under Carter and Reagan) Paul Volcker put the reality of the matter succinctly when he noted that the only “financial innovation” that actually benefited the public in the last twenty-five years was the ATM machine. We are talking little more than an elaborate system of extraction, ultimately backed up by the power of courts, prisons, and police and the government’s willingness to grant to corporations the power to create money.

How does a financialized economy operate on an international level? The conventional story has it that the United States has evolved from being a manufacturing-based economy, as in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s when the country exported consumer goods like cars, blue jeans, and televisions to the rest of the world, to being a net importer of consumer goods and exporter of financial services. But if these “services” are not really “services” at all, but government-sponsored credit arrangements enforced by the power of courts and police —then why would anyone not under the jurisdiction of U.S. law agree to go along with it?

The answer is that in many ways, they are under the jurisdiction of U.S. law. This is where we enter into territory that is, effectively, taboo for public discussion. The easiest way to illustrate might be to make note of the following facts:

The United States spends more on its military than all other countries on earth combined. It maintains at least two and a half million troops in 737 overseas military bases, from Paraguay to Tajikistan, and, unlike any other military power in history, retains the power to direct deadly force anywhere on earth.

The U.S. dollar is the currency of global trade, and since the 1970s has replaced gold as the reserve currency of the global banking system.

Also since the 1970s, the United States has come to run an ever-increasing trade deficit whereby the value of products flowing into America from abroad far outweighs the value of those America sends out again.

Set these facts out by themselves, and it’s hard to imagine they could be entirely unrelated. And indeed, if one looks at the matter in historical perspective, one finds that for centuries the world trade currency has always been the money of the dominant military power, and that such military powers always have more wealth flowing into them from abroad than they send out again. Still, the moment one begins to speculate on the actual connections between U.S. military power, the banking system, and global trade, one is likely to be dismissed —in respectable circles, at least— as a paranoid lunatic.

That is, in America. In my own experience, the moment one steps outside the U.S. (or perhaps certain circles in the U.K.), even in staunch U.S. allies like Germany, the fact that the world’s financial architecture was created by, and is sustained by, U.S. military power is simply assumed as a matter of course. This is partly because people outside the United States have some knowledge of the relevant history: they tend to be aware, for instance, that the current world financial architecture, in which U.S. Treasury bonds serve as the principal reserve currency, did not somehow emerge spontaneously from the workings of the market but was designed during negotiations between the Allied powers at the Bretton Woods conference of 1944. In the end, the U.S. plan prevailed, despite the strenuous objections of the British delegation, led by John Maynard Keynes. Like the “Bretton Woods institutions” (the IMF, World Bank) that were created at that same conference to back up the system, these were political decisions, established by military powers, which created the institutional framework in which what we call the “global market” has taken shape.

So how does it work?

The system is endlessly complicated. It has also changed over time. For most of the Cold War, for instance, the effect (aside from getting U.S. allies to largely underwrite the Pentagon) was to keep cheap raw materials flowing into the United States to maintain America’s manufacturing base. But as economist Giovanni Arrighi, following the great French historian Fernand Braudel, has pointed out, that’s how empires have tended to work for the last five hundred years or so: they start as industrial powers, but gradually shift to “financial” powers, with the economic vitality in the banking sector. What this means in practice is that the empires come to be based more and more on sheer extortion —that is, unless one really wishes to believe (as so many mainstream economists seem to want us to) that the nations of the world are sending the United States their wealth, as they did to Great Britain in the 1890s, because they are dazzled by its ingenious financial instruments. Really, the United States manages to keep cheap consumer goods flowing into the country, despite the decline of its export sector, by dint of what economists like to call “seigniorage” —which is economic jargon for “the economic advantage that accrues from being the one who gets to decide what money is”.

There is a reason, I think, why most economists like to ensure such matters are shrouded in jargon that most people don’t understand. The real workings of the system are almost the exact opposite of the way they are normally presented to the public. Most public discourse on the deficit treats money as if it were some kind of preexisting, finite substance: like, say, petroleum. It’s assumed there’s only so much of it, and that government must acquire it either through taxes or by borrowing it from someone else. In reality the government —through the medium of the Federal Reserve— creates money by borrowing it. Far from being a drag on the U.S. economy, the U.S. deficit —which largely consists of U.S. war debt— is actually what drives the system. This is why (aside from one brief and ultimately disastrous period of a few years under Andrew Jackson in the 1820s) there has always been a U.S. debt. The American dollar is essentially circulating government debt. Or to be even more specific, war debt. This again has always been true of central banking systems at least back to the foundation of the Bank of England in 1694. The original U.S. national debt was the Revolutionary War debt, and there were great debates at first over whether to monetize it, that is, to eliminate the debt by increasing the money supply. My conclusion that U.S. deficits are almost exclusively due to military spending is derived from a calculation of real military spending as roughly half of federal spending (one has to include not only Pentagon spending but the cost of wars, the nuclear arsenal, military benefits, intelligence, and that portion of debt servicing that is derived from military borrowing), which is, of course, contestable.

The Bretton Woods decision was, essentially, to internationalize this system: to make U.S. Treasury bonds (again, basically U.S. war debt) the basis of the international financial system. During the Cold War, U.S. military protectorates like West Germany would buy up enormous numbers of such T-bonds and hold them at a loss so as to effectively fund the U.S. bases that sat on German soil (the economist Michael Hudson notes that, for instance, in the late 1960s, the United States actually threatened to pull its forces out of West Germany if its central bank tried to cash in its Treasury bonds for gold); similar arrangements seem to exist with Japan, South Korea, and the Gulf States today. In such cases we are talking about something very much like an imperial tribute system —it’s just that, since the United States prefers not to be referred to as an “empire”, its tribute arrangements are dressed up as “debt”. Just outside the boundaries of U.S. military control, the arrangements are more subtle: for instance, in the relationship between the United States and China, where China’s massive purchase of T-bonds since the 1990s seems to be part of a tacit agreement whereby China floods the United States with vast quantities of underpriced consumer goods, on a tab they’re aware the United States will never repay, while the United States, for its part, agrees to turn a blind eye to China systematically ignoring intellectual property law.

Obviously the relationship between China and the United States is more complex and, as I’ve argued in other work, probably draws on a very ancient Chinese political tradition of flooding dangerously militaristic foreigners with wealth as a way of creating dependency. But I suspect the simplest explanation of why China is willing to accept existing arrangements is just that its leadership were trained as Marxists, that is, as historical materialists who prioritize the realities of material infrastructure over superstructure. For them, the niceties of financial instruments are clearly superstructure. That is, they observe that, whatever else might be happening, they are acquiring more and more highways, high-speed train systems, and high-tech factories, and the United States is acquiring less and less of them, or even losing the ones they already have. It’s hard to deny that the Chinese may be onto something.

I should emphasize it’s not as if the United States no longer has a manufacturing base: it remains preeminent in agricultural machinery, medical and information technology, and above all, the production of high-tech weapons. What I am pointing out, rather, is that this manufacturing sector is no longer generating much in the way of profits; rather, the wealth and power of the 1 percent has come to rely increasingly on a financial system that is ultimately dependent on U.S. military might abroad, just as at home it’s ultimately dependent on the power of the courts (and hence, by extension, of repossession agencies, sheriffs, and the police). Within Occupy, we have begun to refer to it simply as “mafia capitalism”: with its emphasis on casino gambling (in which the games are fixed), loan-sharking, extortion, and systematic corruption of the political class.

Is this system viable over the long term? Surely not. No empire lasts forever, and the U.S. empire has lately been —as even its own apologists have come to admit of late— coming under considerable strain.

One telling sign is the end of the “Third World debt crisis”. For about a quarter century, the United States and its European allies, acting through international agencies such as the IMF, took advantage of endless financial crises among the poorer countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America to impose a market fundamentalist orthodoxy —which invariably meant slashing social services, reallocating most wealth to 1 percent of the population, and opening the economy to the “financial services” industry. These days are over. The Third World fought back: a global popular uprising (dubbed by the media the “anti-globalization movement”) made such an issue out of such policies that by 2002 or 2003, the IMF had been effectively kicked out of East Asia and Latin America, and by 2005 was itself on the brink of bankruptcy. The financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, which struck as U.S. military forces remained embarrassingly quagmired in Iraq and Afghanistan, has led, for the first time, to a serious international discussion of whether the dollar should remain the international reserve currency. At the same time, the formula the major powers once applied to the Third World —declare a financial crisis, appoint a supposedly neutral board of economists to slash social services, reallocate even more wealth to the richest 1 percent, and open the economy to even more pillaging by the financial services industry— is now being applied at home, from Ireland and Greece to Wisconsin and Baltimore. The response to the crisis coming home, in turn, has been a wave of democratic insurrections, beginning in U.S. client states in the Middle East, and rapidly spreading north across the Mediterranean and on to North America.

The remarkable thing is that the closer the insurrectionary wave spread to the center of power, to the “heart of the world’s financial empire” as our Chinese friends put it, the more radical the claims became. The Arab revolts included every sort of people, from Marxist trade unionists to conservative theologians, but at their core was a classically liberal demand for a secular, constitutional republic that allowed for free elections and respected human rights. The occupiers in Greece, Spain, Israel were more often than not studiously anti-ideological —though some were more radical than others (anarchists played a particularly central role in Athens, for example). They insisted that they were focusing on very specific issues of corruption and government accountability, and thus appealed to perspectives across the political spectrum. It was in the United States that we saw a movement kicked off by revolutionaries that began by posing a direct challenge to the very nature of the economic system.

In part, this is simply because Americans really had no one else to blame. An Egyptian, a Tunisian, a Spaniard, a Greek, can all see the political and economic arrangements under which they live —whether U.S.-supported dictatorships, or governments completely subordinate to the reign of finance capital and free market orthodoxy— as something that’s been imposed on them by outside forces, and which therefore could, conceivably, be shrugged off without a radical transformation of society itself. Americans have no such luxury. We did this to ourselves.

Or, alternately, if we did not do this to ourselves, we have to rethink the whole question of who “we” are. The idea of “the 99 percent” was the first step toward doing this.

A revolutionary movement does not merely aim to rearrange political and economic relations. A real revolution must always operate on the level of common sense. In the United States, it was impossible to proceed in any other way. Let me explain.

Earlier I pointed out that the U.S. media increasingly serves less to convince Americans to buy into the terms of the existing political system than to convince them that everyone does. This is true however only to a certain level. On a deeper level, there are very fundamental assumptions about what politics is, or could be, what society is, what people are basically like and what they want from the world. There’s never absolute consensus here. Most people are operating with any number of contradictory ideas about such questions. But still, there is definitely a center of gravity. There are a lot of assumptions that are buried very deep.

In most of the world, in fact, people talk about America as the home of a certain philosophy of political life, which involves, among other things, that we are basically economic beings: that democracy is the market, freedom is the right to participate in the market, that the creation of an ever-growing world of consumer abundance is the only measure of national success. In most parts of the world this has come to be known as “neoliberalism”, and it is seen as one philosophy among many, and its merits are a matter of public debate. In America we never really use the word. We can only speak about such matters through propaganda terms: “freedom”, “the free market”, “free trade”, “free enterprise”, “the American way of life”. It’s possible to mock such ideas —in fact, Americans often do— but to challenge the underlying foundations requires radically rethinking what being an American even means. It is necessarily a revolutionary project. It is also extraordinarily difficult. The financial and political elites running the country have put all their chips in the ideological game; they have spent a great deal more time and energy creating a world where it’s almost more impossible to question the idea of capitalism than to create a form of capitalism that is actually viable. The result is that as our empire and economic system chokes and stumbles and shows all signs of preparing to give way all around us, most of us are left dumbfounded, unable to imagine that anything else could possibly exist.

One might object here: didn’t Occupy Wall Street begin by challenging the role of money in politics —because, as that first flyer put it, “both parties govern in the name of the 1%”, which has essentially bought out the existing political system? This might explain the resistance to working within the existing political structure, but one might also object: in most parts of the world, challenging the role of money in politics is the quintessence of reformism, a mere appeal to the principle of good governance that would otherwise leave everything in place. In the United States, however, this is not the case. The reason tells us everything, I think, about what this country is and what it has become.

Why is it that in America, challenging the role of money in politics is by definition a revolutionary act?

The principle behind buying influence is that money is power and power is, essentially, everything. It’s an idea that has come to pervade every aspect of our culture. Bribery has become, as a philosopher might put it, an ontological principle: it defines our most basic sense of reality. To challenge it is therefore to challenge everything.

I use the word “bribery” quite self-consciously —and, again, the language we use is extremely important. As George Orwell long ago reminded us, you know you are in the presence of a corrupt political system when those who defend it cannot call things by their proper names. By these standards the contemporary United States is unusually corrupt. We maintain an empire that cannot be referred to as an empire, extracting tribute that cannot be referred to as tribute, justifying it in terms of an economic ideology (neoliberalism) we cannot refer to at all. Euphemisms and code words pervade every aspect of public debate. This is not only true of the right, with military terms like “collateral damage” (the military is a vast bureaucracy, so we expect them to use obfuscatory jargon), but on the left as well. Consider the phrase “human rights abuses”. On the surface this doesn’t seem like it’s covering up very much: after all, who in their right mind would be in favor of human rights abuses? Obviously nobody; but there are degrees of disapproval here, and in this case, they become apparent the moment one begins to contemplate any other words in the English language that might be used to describe the same phenomenon normally referred to by this term.

Compare the following sentences:

“I would argue that it is sometimes necessary to have dealings with, or even to support, regimes with unsavory human rights records in order to further our vital strategic imperatives”.

“I would argue that it is sometimes necessary to have dealings with, or even to support, regimes that commit acts of rape, torture, and murder in order to further our vital strategic imperatives”.

Certainly the second is going to be a harder case to make. Anyone hearing it will be much more likely to ask, “Are these strategic imperatives really that vital?” or even, “What exactly is a ‘strategic imperative’ anyway?” There is even something slightly whiny-sounding about the term “rights”. It sounds almost close to “entitlements” —as if those irritating torture victims are demanding something when they complain about their treatment.

For my own part, I find what I call the “rape, torture, and murder” test very useful. It’s quite simple. When presented with a political entity of some sort or another, whether a government, a social movement, a guerrilla army, or really, any other organized group, and trying to decide whether they deserve condemnation or support, first ask “Do they commit, or do they order others to commit, acts of rape, torture, or murder?” It seems a self-evident question, but again, it’s surprising how rarely —or, better, how selectively— it is applied. Or, perhaps, it might seem surprising, until one starts applying it and discovers conventional wisdom on many issues of world politics is instantly turned upside down. In 2006, for example, most people in the United States read about the Mexican government’s sending federal troops to quell a popular revolt, initiated by a teachers’ union, against a notoriously corrupt governor in the southern state of Oaxaca. In the U.S. media, this was universally presented as a good thing, a restoration of order; the rebels, after all, were “violent”, having thrown rocks and Molotov cocktails (even if they did throw them only at heavily armored riot police, causing no serious injuries). No one to my knowledge has ever suggested that the rebels had raped, tortured, or murdered anyone; neither has anyone who knows anything about the events in question seriously contested the fact that forces loyal to the Mexican government had raped, tortured, and murdered quite a number of people in suppressing the rebellion. Yet somehow such acts, unlike the rebels’ stone throwing, cannot be described as “violent” at all, let alone as rape, torture, or murder, but only appear, if at all, as “accusations of human rights violations”, or in some similarly bloodless legalistic language.

In the United States, though, the greatest taboo is to speak of the corruption itself. Once there was a time when giving politicians money so as to influence their positions was referred to as “bribery” and it was illegal. It was a covert business, if often pervasive, involving the carrying of bags of money and solicitation of specific favors: a change in zoning laws, the awarding of a construction contract, dropping the charges in a criminal case. Now soliciting bribes has been relabeled “fund-raising” and bribery itself, “lobbying”. Banks rarely need to ask for specific favors if politicians, dependent on the flow of bank money to finance their campaigns, are already allowing bank lobbyists to shape or even write the legislation that is supposed to “regulate” their banks. At this point, bribery has become the very basis of our system of government. There are various rhetorical tricks used to avoid having to talk about this fact —the most important being allowing some limited practices (actually delivering sacks of money in exchange for a change in zoning laws) to remain illegal, so as to make it possible to insist that real “bribery” is always some other form of taking money in exchange for political favors. I should note that the usual line from political scientists is that these payments are not “bribes” unless one can prove that they changed a politician’s position on a particular element of legislation. By this logic, if a politician is inclined to vote for a bill, receives money, and then changes his mind and votes against it, this is bribery; if however he shapes his view on the bill to begin with solely with an eye for who will give money as a result, or even allows this donor’s lobbyists to write the bill for him, it is not. Needless to say these distinctions are meaningless for present purposes. But the fact remains that the average senator or congressman in Washington needs to raise roughly $10,000 a week from the time they take office if they expect to be reelected —money that they raise almost exclusively from the wealthiest 1 percent. As a result, elected officials spend an estimated 30 percent of their time soliciting bribes.

All of this has been noted and discussed —even if it remains taboo to refer to any of it by its proper names. What’s less noted is that, once one agrees in principle that it is acceptable to purchase influence, that there’s nothing inherently wrong with paying people— not just one’s own employees, but anyone, including the most prestigious and powerful —to do, and say, what you like, the morality of public life starts looking very different. If public servants can be bribed to take positions one finds convenient, then why not scholars? Scientists? Journalists? Police? A lot of these connections began emerging in the early days of the occupation: it was revealed, for instance, that many of the uniformed police in the financial district, who one might have imagined were there to protect all citizens equally, spent a large portion of their working hours paid not by the city but directly by Wall Street firms; similarly, one of the first New York Times reporters to deign to visit the occupation, in early October, freely admitted he did so because “the chief executive of a major bank” had called him on the phone and asked him to check to see if he thought the protests might affect his “personal security”. What’s remarkable is not that such connections exist, but that it never seems to occur to any of the interested parties that there’s anything that needs to be covered up here.

Similarly with scholarship. Scholarship has never been objective. Research imperatives have always been driven by funding from government agencies or wealthy philanthropists who at the very least have very specific ideas about what lines of questions they feel are important to ask, and usually about what sorts of answers it’s acceptable to find to them. But starting with the rise of think tanks in the 1970s, in those disciplines that most affect policy (economics notably), it became normal to be hired to simply come up with justifications for preconceived political positions. By the 1980s, things had gone so far that politicians were willing to openly admit, in public forums, that they saw economic research as a way of coming up with justification for whatever it is they already wanted people to believe. I still remember during Ronald Reagan’s administration being startled by exchanges like this one on TV:

ADMINISTRATION OFFICIAL: Our main priority is to enact cuts in the capital gains tax to stimulate the economy.

INTERVIEWER: But how would you respond to a host of recent economic studies that show this kind of “trickle-down” economics doesn’t really work? That it doesn’t stimulate further hiring on the part of the wealthy?

OFFICIAL: Well, it’s true, the real reasons for the economic benefits of tax cuts remain to be fully understood.

In other words, the discipline of economics does not exist to determine what is the best policy. We have already decided on the policy. Economists exist to come up with scientific-sounding reasons for us doing what we have already decided to do; in fact, that’s how they get paid. In the case of the economists in the employ of a think tank, it’s literally their job. Again, this has been true for some time, but the remarkable thing is that, increasingly, their sponsors were willing to actually admit this.

One result of this manufacture of intellectual authority is that real political debate becomes increasingly difficult, because those who hold different positions live in completely different realities. If those on the left insist on continuing to debate the problems of poverty and racism in America, their opponents would once more feel obliged to come up with counterarguments (e.g., poverty and racism are a result of the moral failings of the victims). Now they are more likely to simply insist that poverty and racism no longer exist. But the same thing happens on the other side. If the Christian right wants to discuss the power of America’s secular “cultural elite” those on the left will normally reply by insisting there’s isn’t one; when the libertarian right wishes to make an issue of the (very real) historical connections between U.S. militarism and Federal Reserve policy, their liberal interlocutors regularly dismiss them as so many conspiracy-theorist lunatics.

In America today “right” and “left” are ordinarily used to refer to Republicans and Democrats, two parties that basically represent different factions within the 1 percent —or perhaps, if one were to be extremely generous, the top 2 to 3 percent of the U.S. population. Wall Street, which owns both, seems equally divided between the two. Republicans, otherwise, represent the bulk of the remaining CEOs, particularly in the military and extractive industries (energy, mining, timber), and just about all middle-rank businessmen; Democrats represent the upper echelons of what author and activist Barbara Ehrenreich once called “the professional-managerial class”, the wealthiest lawyers, doctors, administrators, as well as pretty much everyone in academia and the entertainment industry. Certainly this is where each party’s money is coming from —and increasingly, raising and spending money is all these parties really do. What is fascinating is that, during the last thirty years of the financialization of capitalism, each of these core constituencies has developed its own theory of why the use of money and power to create reality is inherently unobjectionable, since, ultimately, money and power are the only things that really exist.

Consider this notorious quote from a Bush administration aide, made to a New York Times reporter shortly after the invasion of Iraq:

The aide said that guys like me were “in what we call the reality-based community”, which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.”… “That’s not the way the world really works anymore”, he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality”.

Such remarks might seem sheer bravado, and the specific remark refers more to military force than economic power —but in fact, for people at the top, when speaking off record, just as words like “empire” are no longer taboo, it’s also simply assumed that U.S. economic and military power are basically identical. Indeed, as the reporter goes on to explain, there’s an elaborate theology behind this kind of language. Since the 1980s, those on the Christian right —who formed the core of George W. Bush’s inner circle— turned what was then called “supply-side economics” into a literally religious principle. The greatest avatar of this line of thought was probably conservative strategist George Gilder, who argued that the policy of the Federal Reserve creating money and transferring it directly to entrepreneurs to realize their creative visions was, in fact, merely a human-scale reenactment of God’s original creation of the world out of nothing, by the power of His own thought. This view came to be widely embraced by televange-lists like Pat Robertson, who referred to supply-side economics as “the first truly divine theory of money creation”. Gilder took it further, arguing that contemporary information technology was allowing us to overcome our old materialistic prejudices and understand that money, like power, is really a matter of faith —faith in the creative power of our principles and ideas. Others, like the anonymous Bush aide, extend the principle to faith in the decisive application of military force. Both recognize an intimate link between the two (as do the heretics of the right, Ayn Rand’s materialist acolytes and Ron Paul —style libertarians, who object to both the current system of money creation and its links to military power).

The church of the liberals is the university, where philosophers and “radical” social theorists take the place of theologians. This might appear a very different world, but during the same period, the vision of politics that took shape among the academic left is in many ways disturbingly similar. One need only reflect on the astounding rise in the 1980s, and apparent permanent patron saint status since, of the French poststructuralist theorist Michel Foucault, and particularly his argument that forms of institutional knowledge —whether medicine, psychology, administrative or political science, criminology, biochemistry for that matter— are always also forms of power that ultimately create the realities they claim to describe. This is almost exactly the same thing as Gilder’s theological supply-side beliefs, except taken from the perspective of the professional and managerial classes that make up the core of the liberal elite. During the heyday of the bubble economy of the 1990s, an endless stream of new radical theoretical approaches emerged in academia —performance theory, Actor-Network Theory, theories of immaterial labor— all converging around the theme that reality itself is whatever can be brought into being by convincing others that it’s there. Granted, one’s average entertainment executive might not be intimately familiar with the work of Michel Foucault —most have probably barely heard of him, unless they were literature majors in college— but neither is the average churchgoing oil executive likely to be familiar with the details of Gilder’s theories of money creation. These are both, as I remarked, the ultimate theological apotheoses of habits of thought that are pervasive within what we called “the 1 percent”, an intellectual world where even as words like “bribery” or “empire” are banished from public discourse, they are assumed at the same time to be the ultimate basis of everything.

Taken from the perspective of the bottom 99 percent, who have little choice but to live in realities of one sort or another, such habits of thought might seem the most intense form of cynicism —indeed, cynicism taken to an almost mystical level. Yet all we are really seeing here is the notorious tendency of the powerful to confuse their own particular experiences and perspectives with the nature of reality itself— since, after all, from the perspective of a CEO, money really can bring things into being, and from the perspective of a Hollywood producer, or hospital administrator, the relation among knowledge, power, and performance really is all that exists.

There is one terrible irony here. For most Americans the problem is not the principle of bribery itself (much though most of them find it disgusting and feel politicians in particular are vile creatures), but that the 1 percent appear to have abandoned earlier policies of at least occasionally extending that bribery to the wider public. Since, after all, bribing the working classes by, for instance, redistributing any significant portion of all this newly created wealth downward —as was common in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s— is precisely what both parties’ core constituencies are no longer willing to do. Instead, both Republicans and Democrats seem to have mobilized their activist “base” around a series of constituencies whose ultimate aspirations they have not the slightest intention of ever realizing: conservative Christians, for example, who will never really see abortion illegalized outright, or labor unions, who will never really see the legal hurdles placed in the way of organizing genuinely removed.

The answer to the initial question, then, is that in the United States, challenging the role of money in politics is necessarily revolutionary because bribery has become the organizing principle of public life. An economic system based on the marriage of government and financial interests, where money is transformed into power, which is then used to make more money again, has come to seem so natural among the core donor groups of both political parties that they have also come to see it as constitutive of reality itself.

How do you fight it? The problem with a political order based on such high levels of cynicism is that it doesn’t help to mock it —in a way, that only makes matters worse. At the moment, the TV news seems divided between shows that claim to tell us about reality, which largely consist of either moderate right (CNN) to extreme right (FOX) propaganda, and largely satirical (The Daily Show) or otherwise performative (MSNBC) outlets that spend most of their time reminding us just how corrupt, cynical, and dishonest CNN and FOX actually are. What the latter media says is true, but ultimately this only reinforces what I’ve already identified as the main function of the contemporary media: to convey the message that even if you’re clever enough to have figured out that it’s all a cynical power game, the rest of America is a ridiculous pack of sheep.

This is the trap. It seems to me if we are to break out of it, we need to take our cue not from what passes for a left at all, but from the populist right, since they’ve figured out the key weak point in the whole arrangement: very few Americans actually share the pervasive cynicism of the 1 percent.

One of the perennial complaints of the progressive left is that so many working-class Americans vote against their own economic interests —actively supporting Republican candidates who promise to slash programs that provide their families with heating oil, who savage their schools and privatize their Medicare. To some degree the reason is simply that the scraps the Democratic Party is now willing to throw its “base” at this point are so paltry it’s hard not to see their offers as an insult: especially when it comes down to the Bill Clinton or Barack Obama —style argument “we’re not really going to fight for you, but then, why should we? It’s not really in our self-interest when we know you have no choice but to vote for us anyway”. Still, while this may be a compelling reason to avoid voting altogether —and, indeed, most working Americans have long since given up on the electoral process— it doesn’t explain voting for the other side.

The only way to explain this is not that they are somehow confused about their self-interest, but that they are indignant at the very idea that self-interest is all that politics could ever be about. The rhetoric of austerity, of “shared sacrifice” to save one’s children from the terrible consequences of government debt, might be a cynical lie, just a way of distributing even more wealth to the 1 percent, but such rhetoric at least gives ordinary people a certain credit for nobility. At a time when, for most Americans, there really isn’t anything around them worth calling a “community”, at least this is something they can do for everybody else.

The moment we realize that most Americans are not cynics, the appeal of right-wing populism becomes much easier to understand. It comes, often enough, surrounded by the most vile sorts of racism, sexism, homophobia. But what lies behind it is a genuine indignation at being cut off from the means for doing good.

Take two of the most familiar rallying cries of the populist right: hatred of the “cultural elite” and constant calls to “support our troops”. On the surface, it seems these would have nothing to do with each other. In fact, they are profoundly linked. It might seem strange that so many working-class Americans would resent that fraction of the 1 percent who work in the culture industry more than they do oil tycoons and HMO executives, but it actually represents a fairly realistic assessment of their situation: an air conditioner repairman from Nebraska is aware that while it is exceedingly unlikely that his child would ever become CEO of a large corporation, it could possibly happen; but it’s utterly unimaginable that she will ever become an international human rights lawyer or drama critic for The New York Times. Most obviously, if you wish to pursue a career that isn’t simply for the money —a career in the arts, in politics, social welfare, journalism, that is, a life dedicated to pursuing some value other than money, whether that be the pursuit of truth, beauty, charity— for the first year or two, your employers will simply refuse to pay you. As I myself discovered on graduating college, an impenetrable bastion of unpaid internships places any such careers permanently outside the reach of anyone who can’t fund several years’ free residence in a city like New York or San Francisco —which, most obviously, immediately eliminates any child of the working class. What this means in practice is that not only do the children of this (increasingly in-marrying, exclusive) class of sophisticates see most working-class Americans as so many knuckle-dragging cavemen, which is infuriating enough, but that they have developed a clever system to monopolize, for their own children, all lines of work where one can both earn a decent living and also pursue something selfless or noble. If an air conditioner repairman’s daughter does aspire to a career where she can serve some calling higher than herself, she really only has two realistic options: she can work for her local church, or she can join the army.

This was, I am convinced, the secret of the peculiar popular appeal of George W. Bush, a man born to one of the richest families in America: he talked, and acted, like a man that felt more comfortable around soldiers than professors. The militant anti-intellectualism of the populist right is more than merely a rejection of the authority of the professional-managerial class (who, for most working-class Americans, are more likely to have immediate power over their lives than CEOs), it’s also a protest against a class that they see as trying to monopolize for itself the means to live a life dedicated to anything other than material self-interest. Watching liberals express bewilderment that they thus seem to be acting against their own self-interest —by not accepting a few material scraps they are offered by Democratic candidates— presumably only makes matters worse.

The trap from the perspective of the Republican Party is that by playing to white working-class populism in this way, they forever forgo the possibility of stripping away any significant portion of the Democratic Party’s core support: African Americans, Latinos, immigrants, and second-generation children of immigrants, for whom (despite the fact that they are also overwhelmingly believing Christians and despite the fact that their children are so strongly overrepresented in the armed forces) this kind of anti-intellectual politics is simply anathema. Could one seriously imagine an African-American politician successfully playing the anti-intellectual card in the manner of George W. Bush? Such a thing would be unthinkable. The core Democratic constituencies are precisely those who not only have a more vivid sense of themselves as bearers of culture and community, but, crucially, for whom education is still a value in itself.

Hence the deadlock of American politics.

Now think of all the women (mostly, white women) who posted their stories to the “We Are the 99 Percent” page. From this vantage, it’s hard to see them as expressing anything but an analogous protest against the cynicism of our political culture: even it takes the form of the absolute minimum demand to pursue a life dedicated to helping, teaching, or caring for others without having to sacrifice the ability to take care of their own families. And after all, is “support our schoolteachers and nurses” any less legitimate a cry than “support our troops”? And is it a coincidence that so many actual former soldiers, veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, have found themselves drawn to their local occupations?

By gathering together in the full sight of Wall Street, and creating a community without money, based on principles not just of democracy but of mutual caring, solidarity, and support, occupiers were proposing a revolutionary challenge not just to the power of money, but to the power of money to determine what life itself was supposed to be about. It was the ultimate blow not just against Wall Street, but against that very principle of cynicism of which it was the ultimate embodiment. At least for that brief moment, love had become the ultimate revolutionary act.

Not surprising, then, that the guardians of the existing order identified it for what it was, and reacted as if they were facing a military provocation.

I stumbled upon this article written in 2012 by Naomi Wolf, whose perspective was keen regarding the scamdemic, but not so much when it comes to Zionism.

In any event, here's an excerpt: "The FBI treated the Occupy movement as a potential criminal and terrorist threat … The PCJF has obtained heavily redacted documents showing that FBI offices and agents around the country were in high gear conducting surveillance against the movement even as early as August 2011, a month prior to the establishment of the OWS encampment in Zuccotti Park and other Occupy actions around the country..."

"Why the huge push for counterterrorism "fusion centers", the DHS militarizing of police departments, and so on? It was never really about "the terrorists". It was not even about civil unrest. It was always about this moment, when vast crimes might be uncovered by citizens – it was always, that is to say, meant to be about you."

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/29/fbi-coordinated-crackdown-occupy

Soon, anarchists everywhere were opposed to the idea of making demands. If you weren't making demands, then what was the use of marching on wall street?

Protests always need demands, or a reason to be.

On one hand, he says that making demands of those in power legitimizes their power. Reality states that someone must be in power. If nobody is in power, why march and make demands? Even if it's soft power, like wall street bankers or stock markets, somebody is in power.

United America was a travesty that should have never happened.

I remember the politicians beings super happy about it, that corporations could be counted as people and donate to candidates. They said, "A corporation is a living being. It buys, it sells, it consumes, it spends money." to which I would always say, "True, but you can't kill a corporation like you can a person. corporations don't face the death penalty. Show me a corporation that can die, and I will think you're right."

Trickle down economics doesn't work. If you want to see the economy really take off, drop the draconian tax code, let us keep the money we earn by our hard work. Watch what happens when we are able to use our money the way we want to. It might surprise you.

If people weren't taxed so highly, you'd see people racing to buy an battery charged vehicle. You'd see people spending money on clothes, electronics, books, food, automobiles, and vacations.

That would stimulate the economy.

In a well ordered "Empire," we'd bring the best products from other countries, and send them our best products. We'd try to lift the rest of the world up to our level.

Even the Romans didn't try to bankrupt their vassal states, they traded with them, while providing police and military assistance.