CANADIAN NIGHTMARE (PART 1)

How the Port Coquitlam RCMP Protected Serial Killer Robert Pickton

Hey Folks,

Welcome to the first instalment of Canadian Nightmare!

In this series, I will doing a deep dive to prove that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police has blood on their hands vis-a-vis the gruesome crimes of serial killer Robert Pickton and his accomplices.

MY PREVIOUS ARTICLES ABOUT MISSING AND MURDERED INDIGENOUS WOMEN IN B.C.

August 13, 2022 - Ten Things You Need to Know about the Drug War Right Fucking Now

August 20, 2022 - Indigenous women are still being murdered in Vancouver, and the police are still are covering it up

August 21, 2022 - Will Five Billion Dollars be Enough to Cover Up Vancouver’s Dirty Little Secret?

October 3rd, 2023 - Robert Pickton is Eligible for Parole in 2024

March 1, 2024 - Robert Pickton is Up for Parole

May 2024 - Who Killed Robert Pickton?

June 19, 2020 - The Never-Ending Nightmare

CANADIAN NIGHTMARE (PART 1)

BASED ON THAT LONELY SECTION OF HELL: THE BOTCHED INVESTIGATION OF A SERIAL KILLER WHO ALMOST GOT AWAY

The information I will share in this series is based on a book called That Lonely Section of Hell, which was written by a former Vancouver police detective by the name of Lori Shenher.

The first thing that I’ll say about the book is that it’s a very good book. Lori Shenher writes passionately, and despite the fact that she was a cop, I couldn’t not empathize with her.

I truly believe that Shenher did her best to find the missing women, and that her investigation was stymied by her superiors. Indeed, she describes her experience with the Vancouver Police Department as highly traumatic, and she left police work after being diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. She now describes herself as a “recovering cop”.

The second thing that I’ll say about That Lonely Section of Hell is that a lot of it is about the author’s battle with PTSD. If it were only about her policing work, the book would be way shorter.

Because the part of this story that most interests me regards the Pickton case, I have decided to mine the book for the most important information it contains.

The third thing that I’ll say is that this book is the very definition of a “limited hangout”.

WHAT IS A LIMITED HANGOUT?

According to Wikipedia:

A limited hangout or partial hangout is a tactic used in media relations, perception management, politics, and information management. The tactic originated as a technique in the espionage trade.

Basically, a limited hangout is when authorities give you part of the truth, whilst simultaneously withholding key information. The intention is to mislead the public by selectively releasing part (but not all) of the truth.

According to [C.I.A. agent] Victor Marchetti, a limited hangout is "spy jargon for a favorite and frequently used gimmick of the clandestine professionals. When their veil of secrecy is shredded and they can no longer rely on a phony cover story to misinform the public, they resort to admitting—sometimes even volunteering—some of the truth while still managing to withhold the key and damaging facts in the case. The public, however, is usually so intrigued by the new information that it never thinks to pursue the matter further."

It is evident that Shenher does not reveal everything that she knows about the Pickton case. Indeed, she explicitly states:

There is no information contained in this book about the victims or their families that has not already been in the public domain through the trial of Robert Pickton or the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry.

Huh. That’s kind of disappointing, isn’t it? I was kind of hoping that a book written by a detective about a “botched investigation” would include new information.

The book is very, very compelling, but if you happen to know a lot about the Pickton case, some omissions really make you wonder.

For example, Shenher fails to mention that Canadian authorities failed to issue any cash reward for information leading to the missing women. Eventually, a $100,000 reward was offered after Vancouver police were persuaded by the producers of America’s Most Wanted, which brought the story of Vancouver’s missing women to an international audience in 1999. Shenher briefly mentions flying to the U.S. to consult to meet America’s Most Wanted production team, but she doesn’t tell the full story.

Shenher also places the blame for the botched investigation more on the Port Coquitlam RCMP than on her former colleagues at the Vancouver Police Department.

On that last point, she does make a convincing case. There is plenty to condemn about the actions (and inactions) of the VPD, but they pale in comparison to the Port Coquitlam RCMP, who seemed to have been blatantly protecting Pickton.

Although Port Coquitlam is now a residential suburb of Vancouver, it is its own municipality. It is policed by the RCMP, meaning that the VPD did not have jurisdiction to raid the farm.

At this point, none of this is particularly mysterious. We know that the RCMP has deep ties to organized crime, and it appears that the Port Coquitlam RCMP prevented the VPD from obtaining a search warrant in order to protect the Hells Angels.

Robert Pickton and his siblings, who co-owned the infamous pig farm, were connected to the Hells Angels biker gang, who have long wielded considerable power in Canada.

The B.C. RCMP are known to have deep connections to the Hells Angels, and members of that police force were regular guests at parties hosted by Robert Pickton and his brother David at a venue called Piggie’s Palace.

THE VPD INVESTIGATION INTO VANCOUVER’S MISSING WOMEN WAS STYMIED BY THE RCMP.

To me, the biggest takeaway from That Lonely Section of Hell is the extent to which the VPD’s investigation into the Pickton farm was stymied by the RCMP.

The property was located in the Vancouver suburb of Port Coquitlam, where the RCMP have jurisdiction.

Although the VPD sure doesn’t come out of this story smelling like roses, it’s clear to me that the RCMP did more to obstruct justice than the VPD did.

Oh yeah, I should probably quickly mention that in 2015, Lori underwent elective surgery and began identifying as male, adopting the name Lorimer.

To avoid confusion, I will refer to her using female pronouns, as she was female for the entire duration of her career as a detective.

WHO IS LORI (OR LORIMER) SHENHER?

Lori Shenher was a reporter for the Calgary Herald before moving to Vancouver to become a cop. At one point in her book, she confesses that her dream was to become a fiction writer. She says that she became a cop in order to gain life experience that would make her a more compelling writer.

Be careful what you wish for, I guess.

I had chosen policing in large part because it afforded me the time off and subject matter to enable me to pursue my writing as a hobby, yet I felt duty-bound to not share a large portion of what I’d seen and done. All my life, I'd assumed I would pursue fiction as a writer, but the truth was far more compelling.

The book begins with Shenher speaking about her early work with the VPD, which involved a stint as a vice cop.

In November 1991, on my graduation from the police academy, the VPD assigned me to a patrol unit on the Downtown Eastside. Shootings, break-ins, robberies, stabbings, suicides, and sexual assaults filled the hours of my shifts.

In 1993, I was pulled from my squad to work a special assignment with the now-defunct Prostitution Task Force (PTF), a two-man unit given the dual assignment of identifying Downtown Eastside sex workers and conducting undercover “John Stings.”

I posed as a sex worker two nights a week for six months, standing on the cold streets between six and ten hours at a time, making verbal deals with men to exchange sex for money. Over that rainy Vancouver winter, my life was threatened, objects were tossed at me from cars, I was nearly abducted at gunpoint, and I endured the less dramatic indignities of shivering in a too-short dress and suffering in high heels. I did not know the pain of drug withdrawal, addiction, loneliness, hunger, spousal abuse, or sleeping rough that other sex workers deal with, but still, I felt miserable.

Here’s a picture of her dressed up for undercover work.

In 1994, she was assigned to a patrol unit on Vancouver's west side, where she remained until 1996, when she joined the Strike Force, VPD’s elite surveillance unit.

In 1998, she was transferred to the Missing Persons Unit, becoming the first and only cop whose full-time job was searching for Vancouver’s missing women, most of whom were drug-addicted sex workers.

She writes:

I began my assignment in the Vancouver Police Department’s (VPD) Missing Persons Unit in July 1998, and in the first week, I received an anonymous Crime Stoppers tip that implored me to look at a man named Willie Pickton, who lived on a farm in Port Coquitlam, a community about eighteen miles outside of Vancouver.

The tipster said Pickton bragged to his friends about his ability to dispose of bodies on his property and he offered them the use of his grinder. The tipster believed Pickton could be responsible for the deaths of the missing women. Thus began my repeated futile attempts to convince the police of that jurisdiction—the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)—to investigate Pickton, while I continued my own search for the women.

Yep. You read that right. Shenher heard about Pickton in July 1998. He wasn’t arrested until 2002. You can’t make this shit up.

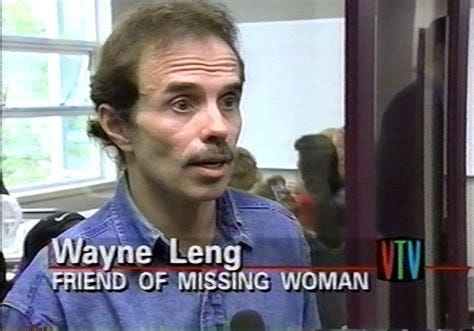

In April 1998, a woman named Sarah de Vries had disappeared, and a friend of hers, Wayne Leng, had set up a 1-800 tip line. Wayne was a single middle-aged man who worked in the automotive industry and had an interest in computers.

On July 27, 1998—my first day working in the VPD Missing Persons Unit—a man named Bill Hiscox phoned Wayne's tip line suggesting that Robert William Pickton be considered a suspect in the disappearance of Sarah and the other missing women.

It would be several days before this information would reach me, and I would work feverishly to interview Hiscox myself and search for any links between the victims and the Pickton farm.

WAYNE LENG IS A CANADIAN HERO

Wow! How fucking crazy is that? It sounds like this Wayne Leng guy basically solved this case, doesn’t it? Shouldn’t we be celebrating this guy as a Canadian hero?

Shenher continues:

Once I possessed a basic grasp of the victim files, I had Wayne Leng come in for an interview in mid-August of 1998. All of our telephone dealings to that point had been uneventful. Wayne was small and compact and wore glasses. He spoke softly, with a slightly high-pitched voice, and he seemed gentle and kind. I found him to be helpful, conscientious, and knowledgeable about the Downtown Eastside—all traits that alternately comforted and worried me. I continued to ask myself if he could be a serial killer. The only way to rule him in or out was to go at him hard, and I did. I questioned him about why he would put everything in his life on the back burner for this woman who had such problems, who so clearly couldn't give Wayne the kind of love that he had to give. He simply said he was patient and knew she had the potential to live a good life and be a solid citizen. Try as I might, I couldn’t anger him—specifically, I couldn’t bring him to express anger at Sarah.

I asked Wayne if he would be willing to take a polygraph, and he agreed, saying he would do whatever I asked if it would help. He would call me several times a week with information…

In a July 1998 conversation with Wayne Leng, Bill Hiscox said that a “Willie” Pickton had a large farm in Port Coquitlam, a suburb of Vancouver, and often bragged about his ability to grind up bodies and dispose of them. He knew a woman who had been in Pickton’s trailer and had seen several women’s purses and identification cards and “bloody clothing in bags.” Leng encouraged Hiscox to call me, but instead, he called Crime Stoppers and left a tip that Pickton was someone we should look at. A few weeks later, he left a second tip with the same message. As is typical with Crime Stoppers tips, Hiscox left these anonymously. When the tips reached me, I immediately researched everything I could get my hands on about the man I would come to know as Robert William Pickton.

[…]

I sat down at the RCMP Police Information Retrieval System (PIRS) terminal and entered Pickton’s name and date of birth. Electrified, I read that he had one entry on his criminal record—a 1997 stay of proceedings for attempted murder and forcible confinement in Port Coquitlam. As I searched through the details, I learned the victim was a sex worker picked up from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, and both she and Pickton had nearly died from knife wounds that night.

“BINGO!” I shouted, nearly jumping up out of the chair, thinking, This is what a serial killer looks like!

[…]

From this research, I tracked down the Coquitlam RCMP officer who had been in charge of the file, Corporal Mike Connor. A couple of days after we received Hiscox’s tip, I reached Mike on the phone. It was obvious that Pickton was someone he wanted in jail and thought about often, and that this particular event bothered him deeply.

He told me that Pickton had picked up [Wendy Lynn Eisletter], an Indigenous woman and Downtown Eastside sex worker, and taken her to his farm in Port Coquitlam for sex. Somehow, the date had gone wrong, and Pickton and [Eisletter] ended up in a life-and-death struggle in which they each received serious stab wounds—Pickton a single wound, [Eisletter] multiple wounds. Both managed to get themselves to the hospital, and despite having cardiac arrest twice on the operating table, [Eisletter] lived. Pickton’s injuries were less severe, but he later alleged that the interaction with [Eisletter] had left him with hepatitis.

“Do you know why the charges were stayed?” I asked Mike, certain he’d be able to tell me the reasons behind the Crown’s decision to drop the case.

“No. It seemed as though it had something to do with her drug use, that they didn’t think she'd make a credible witness because of her habit.”

“What does that have to do with anything?” I asked, incredulous.

“I don’t know. I'll go out and have a talk with the Crown prosecutor again now that this has come up,” he went on. “I never really understood it, either. If she'd died on the table, we'd have had him cold for murder.”

We agreed that we would keep in touch and that I would let him know if I tracked down the Crime Stoppers caller we would come to know as Hiscox. After talking to Mike, I was certain Pickton was worth pursuing. In the meantime, Leng continued to push Hiscox until he finally agreed to contact me.

Of all the people in Pickton’s circle, it is Hiscox I have the most respect for, because he is the one person who seemed driven by altruism. He became involved at his own peril and without any personal agenda that I’m aware of. He had his own problems, including drug addiction, alcohol abuse, and difficulties with his marriage. Work was scarce and he was collecting welfare benefits. For more than a decade, his substance abuse had frequently landed him in jail for violence or property crimes, and his record was long. He has since spoken quite openly about his struggles.

But Bill Hiscox understood the concept of doing the right thing, and among the vast number of men who had been on the Pickton property over the past twenty years, he was the only one who put himself on the line and told me when we first spoke, “What's going on at this place is wrong, and if girls are getting killed, he [Pickton] needs to be stopped.” Despite the scores of men and women who had heard the rumors, had seen the oddities, had been to the parties and participated—perhaps unwillingly, perhaps not—in the depraved games we learned about after Pickton’s 2002 arrest, Hiscox was the only one who felt it was important enough to say something…

“AN EXCELLENT WITNESS”

Within these short weeks, I'd been led to an excellent potential suspect, and I could barely contain my excitement. This was exactly the type of tip I had envisioned receiving when I took this case, and I eagerly followed it up. I imagined what could be happening on that farm. I knew Pickton possessed at least one backhoe, and I pictured him digging bunkers, perhaps to hold his captives alive or to bury them. My mind ran through all sorts of possibilities as I prepared myself to question Hiscox about what he knew of the place. I researched other cases like this in the U.S. and the U.K. and knew that hidden rooms and torture chambers were not outside the realm of possibility for such depraved killers. I felt an urgency to get on the farm in case there was a chance that any of the women might be rescued. I lay awake at night plotting legal ways we could get on the farm to learn more.

I ruminated on my conversation with Mike Connor about why the 1997 charges against Pickton had been stayed. He was obviously frustrated by his impression that Crown counsel hadn’t felt confident of a conviction because of [Eisletter’s] drug use and alleged unreliability. I found this bizarre. One hundred percent of my court experience had been in the Provincial Court of British Columbia and the B.C. Supreme Court, and if every case involving offenders and victims with drug problems or credibility issues were thrown out, those courtrooms would be vacant.

I also knew from my time on the Downtown Eastside that a drug problem didn’t automatically turn a person into an idiot or a liar or give them amnesia. We agreed that had [Eisletter] died from her injuries, the case would be a slam-dunk murder or at least manslaughter conviction. Mike told me he was exploring ways to have that case reopened, and I sensed he was understating how important this was to him. We agreed to meet and review the file, which we did a bit later in August, after Mike returned from summer vacation.

Reading Mike’s file filled me with a deep sense of foreboding. I felt even more strongly that we were onto something with Pickton. Over and over, I kept thinking, Nobody tries this the first time out of the gate; he’s done it before. I viewed the entire case rather clinically at this point; there was no room for emotion or thinking of my victims as real people. I felt the protective professional detachment from emotion that had served me so well in my career thus far—though that wouldn't last.

As I looked more closely at the files of the missing women reported to our office, I saw the spike in numbers starting in 1995. From 1978 to 1992, six women remained missing and I couldn't see any who were missing from 1993 to 1995. With a jolt, I realized there were three women still missing from 1995, two from 1996, and five from 1997. And 1998 was shaping up to surpass them all with eleven, and the year wasn’t over. Twenty-one Downtown Eastside women missing since 1995. I didn’t need Rossmo’s analysis to tell me someone was killing these women, but backing up my suspicions with science might help me get the resources I was going to need.

I became more convinced that Pickton was our man. Mike and I agreed to place an entry in the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) system flagging Robert Pickton as a person of interest in the missing women investigation and asking any police members who came in contact with Pickton to page both Mike and me at any time, twenty-four hours a day.

From the time I first became aware of Pickton, in July, I had been trying to locate [Eisletter] for an interview, but she had been living on the street, and whenever I would find out where she had slept the previous night, she’d be gone by the time I got there. On August 21, my opportunity finally arrived.

[Eisletter] had been arrested. After a wild cocaine binge in skid row, she resisted arrest and drove off in a police car left running at the scene when the officers it belonged to—one of them a very good friend of mine—had tried to arrest her. She drove into a wall in the same block and found herself facing a number of charges in the Burnaby Correctional Centre for Women.

[Eisletter] and I knew each other from my patrol days on the Downtown Eastside, and when I asked to interview her at the correctional center, she was cooperative and affable; she had been there several days, free of the drugs that made her paranoid and violent. We talked for nearly two hours, and she told me about that fateful night in March 1997 when she had met Robert Pickton. Her story was riveting. I had no doubt that she was telling the truth and that she had been in a fight for her life.

Her recollection of the events mirrored her previous statement perfectly—typical for someone who has been through significant trauma and is telling the truth. Lies are easy to tell once, but they are almost impossible to retell identically. Listening to her, I couldn’t understand why anyone wouldn't find her or her story credible. She would have made an excellent witness in court; she just would have needed someone to take care of her and ensure that she wasn’t using drugs on the days of her testimony.

ENTER BILL HISCOX

In August 1998, I made several unsuccessful attempts to reach Bill Hiscox at the number he left Leng, and we finally spoke on the phone early in September after I tracked him down to a men’s shelter. I left him a message, and he returned my call later that night. A phone conversation is never optimal when dealing with a source, but it marked a beginning I hoped would lead me to a face-to-face meeting so that I could better determine his credibility and his motivation for coming forward.

We spoke easily, and I found him to be reasonable and lucid. He made no mention of a reward—not that one had been offered yet—and he did not ask for payment. He spoke intelligently and answered thoughtfully, and I liked him.

"I'm not working out there anymore," Hiscox told me. "He’s a creep, odd duck, you know? Like, we just never got on that well. I think he just put up with me because Lee said I was okay."

"How did the grinder thing come up?" I asked.

"I dunno. We'd be sitting around, shooting the shit, and Willie'd say, ‘Hey, if any of you guys ever need to get rid of a body, I got this here grinder that works like a hot damn. You're welcome to it.’ And that was Willie, always giving people his stuff, then getting pissed if people took advantage."

"Did he only offer the grinder the one time?"

"No, I remember him saying it a few times, like to other people. He seemed kinda proud of it."

"So, why were you so hot to talk to the police about him?" I wanted to test him a little, see if he was motivated by money or a grudge.

"Well, why do you think?" He seemed annoyed at my question. "If he’s killing girls, he needs to be stopped. I may be a lot of things, but I know what’s right, you know? What Willie’s doing, it isn’t right. If that was my sister, I’d sure as shit want someone speaking out to stop it."

So, turns out that this is what a Canadian hero looks like:

He told me he was trying to clean up his life and get his own place. He told me about his friend Lisa Yelds, nicknamed Lee, a good friend of Pickton’s who arranged for Hiscox to work on the farm as a laborer. This was typical of Pickton—he seemed to have platonic relationships with women living on his property and sexual relationships with sex workers.

Although Hiscox characterized Yelds as a close friend of Pickton’s, he said she had expressed concerns to Hiscox that Pickton might be drugging her and possibly touching her while she was unconscious, but she wasn’t certain. Neither she nor Pickton drank alcohol or used drugs. Hiscox often described Pickton as a “creepy guy” and told me how Pickton had picked up a sex worker downtown, taken her back to his place for sex, then stabbed her. I knew he was talking about [Eisletter].

"Did you know the girl he stabbed?" I asked.

"Nah, no idea. Some girl he picked up downtown, I think. He was pissed, said she gave him hepatitis. Said he’d pay us to bring her back to the farm so he could finish her off."

"You heard him say that?"

"Oh yeah, a few times to different people. Lee said he asked people to find her all the time. He blamed her for his being sick."

I was keenly interested in having a conversation with Lisa Yelds or finding a way to place an undercover operator in a position to befriend her, but Hiscox was certain she would not want to talk. From Hiscox’s description of her, it was clear that she was at best incredibly anti-police and was not interested in helping anyone other than her closest longtime friends. It was obvious that Hiscox felt affection and loyalty toward her, in part because their friendship extended back many years.

Both Yelds and Hiscox were afraid of the Picktons’ biker associates and of being known as police informants within their own peer group. In the 1980s and ’90s, the Picktons were well known in the community. Their parties were notorious in the Port Coquitlam area.

The family owned several large properties that they would eventually sell to the city, which subdivided them for developments and big-box stores such as Home Depot. Before that, Robert and his brother, Dave, lived on one property, and on another property a mile down the road, there was a large barn known as Piggie’s Palace, where, according to local lore, those parties took place and were well attended by many in the community, including elected officials and police. Although there were rumblings of illegal after-hours liquor activity, for the most part, it sounded like relatively good clean fun, at least on the surface.

Down the road from Piggie’s Palace was quite another story. Robert lived in the small dirty mobile office trailer farther back from the road, and Dave inhabited the house near the front of the large lot. Large mounds of recently moved earth, piles of junk metal and lumber, derelict cars, and numerous backhoes littered the property. The brothers owned and operated P&B Salvage Company, and the farmland was their storage area. There was also a barn and attached slaughterhouse where Robert butchered his pigs and lambs, selling the meat to friends and local sellers.

None of the sex workers I spoke with agreed to go on the record with what they saw and experienced on the property shared by Robert and Dave, but several told me stories of depraved sex “games,” many involving non-consensual sex acts and torture; drugs laced with unknown hallucinogens; and pigs exhibiting an unnatural interest in humans.

As one woman described to me shortly after the Pickton search began in 2002:

"I was in the trailer, you know, we were partying and some of the guys were getting pretty into it, taking girls into the other room and around the side. Dope everywhere. I was using a lot back then, so my memory isn’t the best, but I knew what I was doin’. Someone gave me some smack and as soon as I shot it, I felt sick, really weird, not like trippin’, more like sick. Just not the way a high feels.

"So, I say I’m going out for some air and no one really stops me, so much is going on and everyone's fucked up, right? And I go around the trailer, it’s a really nice night, not raining for once. My head’s swimming, so I just walk. I'd never been out there before, so I walk for some air and I turn a corner and there’s a pigpen. I grew up in the country, I know pigs, so I walk over to the fence to have a look, I’m feeling a little better. And out of fucking nowhere these pigs are throwing themselves at the fence where I’m standing like they want to get at me. I never seen pigs act like that, pigs are gentle. But it was like they could smell me, smell my woman-ness. They scared the shit out of me and I got the fuck away from there."

Hiscox agreed to think of ways to obtain more information from Yelds but wasn’t confident she would cooperate. He offered to try to spend some time on the farm, but I suggested he do so only if it was convenient for him and if that appeared normal to Yelds and Pickton. I didn’t want him doing anything outside of his normal routine, and I didn’t want to give him the impression that I was directing him. At this point, I didn’t know enough about him to have him acting as an agent for the police, and I didn’t want him doing anything to put himself at risk or to tip Pickton off that he might be a police source. We agreed to speak again in a few days, and I continued to assess his true involvement in the activities on the Pickton farm.

I marveled at his dedication to trying to do the right thing, even when it was less than convenient for him. I never got the sense it was about money; he received no money from me or from the RCMP during the investigation, and he never asked me for anything that might have been available to him as a source. The most he ever got before Pickton’s arrest was a cup of coffee from Mike and me.

My goal that day was to get to know as much about Hiscox, Yelds, and Pickton as possible. Hiscox responded fully and thoughtfully to my questions and gave me personal details about his life, his history, and his hopes for the future. He told me he was the tipster to Crime Stoppers and also said that Wayne Leng had given some members of the media his name. He had been contacted in July for information, but he did not provide any, and eventually they stopped hounding him. He clearly wasn't after public notoriety.

Hiscox had met Pickton and his brother, Dave “Piggy” Pickton, through Lisa Yelds, who also arranged for Hiscox to work for the brothers for a couple of months at P&B Salvage. He found Robert Pickton very quiet, with no sense of humor, and didn’t like being around him, but he assured me he had no problems with Pickton; there was no money owed between them, and they were not involved in drugs or other criminal activities together. Since sources often minimize their business dealings with other shady characters, I took this information with a grain of salt and remained open to the idea that they could be more closely connected.

Yelds and Pickton used to date and still got together here and there. Pickton had no other girlfriend that Hiscox knew of and used the services of sex workers regularly, a piece of information Hiscox also learned from Yelds. He characterized Yelds and Pickton as “best friends.”

“Lee said Willie asked her to get him syringes; she always gets him things in exchange for meat. She’s like his contact for stuff.”

“What are the syringes for? She doesn’t use, right?”

“No. She said he wants them for a girl named [Eisletter], half clean and half dirty needles.”

“Any idea why?”

“No idea. I never heard of that before, the clean and used thing. Lee says Willie wants to get this girl. Lee thinks to hurt her in some way. I think this [Eisletter] might be the girl who gave him hep, maybe. I don’t know.”

Hiscox felt certain Lisa Yelds wouldn't talk to me because she was loyal to Pickton as a friend and business associate.

Yelds was a longtime biker associate and someone who would never “rat out” a friend—especially to the cops. Hiscox characterized Yelds as someone who “just doesn’t give a crap” and was a borderline “psycho” at times herself. He said someone could be lying on the ground bleeding and she’d just step over him or her and carry on. He said she was generally quite cold but was loyal to Hiscox because they grew up in foster care together and she had stuck up for and protected him when he was a kid. Hiscox reiterated several times how much she hated cops.

Despite the volume of information he gave me about Yelds, I got the feeling he didn’t want me to know too much about her. He gave me her phone number but said he doubted she would talk to me. He didn’t feel he could even approach her to let her decide, but he said if I went with him and met her casually and we didn’t tell her I was a cop, she would probably relay a lot of this info about Pickton in front of me.

I hesitated to call Yelds, since I was afraid that might put Hiscox at risk if he returned to the farm. He agreed to introduce an undercover operator to Yelds if we asked him to—perhaps portraying her as a new girlfriend if we decided to use him as an agent. He assured me that Yelds would not be suspicious; apparently, she did not like Hiscox’s estranged wife and would not think it odd for him to bring a new girl around to meet her. We didn’t discuss the details or implications of the operation, but I got the sense that Hiscox hoped I could be the undercover operator.

Although I had had numerous undercover assignments in my career, I hadn’t undertaken one that might turn into a days- or weeks-long operation. I was an investigator now, and although the prospect was enticing, I knew there were better people for the job. Six months earlier, I’d have jumped at an offer, but I felt a strong commitment to the work I'd begun with the missing women. I decided I would turn down the offer if asked and maintain my role as file coordinator and lead investigator.

Hiscox said Yelds told him within the past week that Pickton had some “weird things around the house,” and this led to her divulging he had several women’s purses, items of jewelry, and bloody clothing in bags and that her impression was he kept them as trophies.

“She says she thinks he could be responsible for those missing Vancouver girls,” Hiscox told me.

“Is she scared of him?” Hiscox laughed at this.

“What’s so funny?” I asked.

“You just gotta know Lee,” he said, shaking his head, still chuckling. “It doesn’t surprise me she'd still hang with him. That’s just how she is. She doesn’t give a damn.”

“Do you think she’s in danger? Are you worried about her?”

“Nah. You gotta know Lee. She'll be cautious. She said she keeps one eye open around him now.”

I drove back to Vancouver feeling hopeful we could make some inroads into Pickton’s activities through Lisa Yelds.

When I got back to my office, I told [my supervisor] about my dealings with Hiscox, and we agreed that this should be an RCMP investigation, since the farm was in the Coquitlam RCMP jurisdiction. I had already phoned and left a message for Mike Connor on my way home.

Mike and I played phone tag for several days and finally spoke in late September. He was excited by this new information and the progress I was making with Hiscox, but he was also deeply concerned about the threat to [Eisletter]. We felt it was imperative that he find her and warn her she could be in danger.

We also agreed that Mike would request the services of Special O—the RCMP surveillance unit—to follow Robert Pickton. Within two days, Mike had arranged for surveillance coverage on Pickton from four o'clock in the afternoon until whatever time they “put him to bed”—surveillance jargon for when the team members feel the likelihood that the target will go out again before dawn is minimal. For a man suspected of picking up sex workers in the later hours, this would not be easy.

[…]

At any rate, we were given three days of Special O’s time, and Pickton did little to arouse suspicion. He did not try to pick anyone up; nor did he spend any significant time on the Downtown Eastside other than to conduct what appeared to be business relating to his farm.

You read that right. Pickton was put under surveillance for a mere three days. What kind of serial killer is so prolific that he kills someone every other day?

In the meantime, I had heard from Mike that many members of the Coquitlam RCMP knew the players in a well-established criminal group in Coquitlam, including Yelds. He asked me whether my source had mentioned her, and I had to tell him yes.

On October 13, I tracked Hiscox down to a Maple Ridge drug treatment center. I left a message for him, and he returned my call within an hour. Mike also told me that his superiors had no appetite for an undercover operation. At least Mike was there to advocate for the file and protect Hiscox, and that was somewhat comforting to me.

Hiscox was not happy when I told him that the RCMP wanted to contact Yelds directly, but he agreed to meet with Mike and me. He remained very concerned Yelds would discover he’d been talking to the police. He said he would trust whatever I decided and would do what I thought was best. I felt the weight of responsibility that he would place this degree of faith in me, and I vowed to do everything I could to look out for his interests as long as he continued to be on the level with me. I told him that I thought passing him over to the RCMP—ideally, Mike would handle him—would be better than them going straight to Yelds, and he agreed. But he wanted to be out of the picture sooner than later, and he didn’t want Yelds to know that he had led the cops to her.

In October 1998, Shenher met again with Hiscox, along with Port Coquitlam RCMP constable Mike Connor.

“Can you go through everything that happened that led you to contact Lori, from the beginning for me? I know it’s repetitive for you, but it'll help me know where we're at,” Mike asked.

Hiscox repeated what he'd told me and delved further into Yelds’s contacts than he had with me because Mike was much more familiar than I was with the players in the Coquitlam outlaw motorcycle gang scene of years gone by. I could tell immediately that Mike saw that Hiscox was the real deal and knew all the players and history.

“Lee saw IDs and bloody clothing in bags when she was cleaning in Willie's trailer, that’s what got her to tell me about it,” Hiscox said. “She put two and two together with the offer to get rid of bodies in the grinder and the stories about the missing girls on the news and the girl who he stabbed who he says gave him hep. She thinks Willie could be a serial killer, but she’s no rat and doesn’t want to do anything about it.” He snorted lightly. “So, she tells me—and me, I can’t just sit on this, I have a duty to do something and I can’t live with my conscience and stay quiet about it.” He continued telling Mike all he had shared with me.

“Anything else you can think of?” Mike asked. “Anything new?”

“Yeah, Lee also said she saw a purse she thought belonged to a native girl, like it had one of those dream catchers hanging off it. Said she saw that one a couple of years ago now.”

[…]

“How do you think we should approach Lisa if we were going to?” Mike asked.

“You have to know Lee. She’s tough and she’s no rat. It'd have to be undercover. You couldn't, like, knock on her door and say, ‘We're the cops, can we talk to you for a sec.’” Hiscox laughed. “Yeah, she wouldn’t go for that. She'd slam the door in your face. She hates cops.”

“So, you think an undercover operation is the way to go with her.” Mike asked. “Would she trust a new person in her life?” “Not easily, for sure. But if they came with me, she'd let them in.”

At this point, Shenher’s superiors in the VPD were apparently supportive, offering her resources as she prepared to investigate further.

I called Mike Connor and told him about this offer, but something had happened on the Coquitlam RCMP end. They no longer seemed hot to speak to Yelds, for reasons unknown to me. Mike didn’t know what had changed.

It was at this point in the investigation that I began to realize how priorities shifted from one minute to the next in policing organizations—both the RCMP and the VPD—and how something that seemed to be the most pressing matter one minute could be moved to the back burner the next. It seemed that someone could just decide a file wasn’t important anymore, with no real basis in fact for that decision and no documentation, certainly none that I would be shown. This was the first of many deaths of the Pickton investigation during my time working on it.

Hiscox continue to struggle with his addiction, but never rescinded his offer to help in whatever way he could. And basically, that’s all she wrote.

Actually, that’s not quite true. One thing changed. Mike Connor, the Port Coquitlam cop who Shenher regarded as an ally, was reassigned.

According to a 2012 CBC article:

"Shenher and Connor should have got a lot more praise than what they got for doing what they did," Hiscox said, describing both as fine officers. "They really bent over backwards trying to expose this. And the [police] departments? Shame on you."

"I came forward because I had, well, I guess a bit of a conscience," said [Hiscox], who now loads trucks and has been living in Alberta of late. "When you know something's happening and nobody is doing anything about it, you gotta say something."

Shenher phoned Connor to discuss Hiscox's information after she got a hit in a shared police database matching parameters about missing sex trade workers to the near-fatal stabbing of a prostitute in March 1997. Pickton had been accused of attempted murder in the attack, but the charge was later dropped.

The two officers met with Hiscox several times, looking for ways to corroborate his second-hand information. They felt it wasn't quite enough to trigger a search warrant.

They contemplated using him as an agent in an undercover operation, but for a time, he fell off the map. Connor was promoted and transferred off the case, to his reluctance, and work on the case fizzled.

"They had him right under their radar big time and they just shut 'er down," Hiscox said, adding that to him, the case appeared "open and shut."

"The problem is the red tape and the politics of the police departments," said Hiscox, adding that improper cash flow and a disregard for the lives of sex workers, in his mind, were also likely factors…

Hiscox was never called to testify at Pickton's trial. He confirmed that he received a small portion of the $100,000 reward money that wasn't offered until several years after he went to the police. He said he's ready and willing to testify at the inquiry should he be called.

Anger and frustration still churns in the man's own gut, he said, looking back at the sickening crimes he tried to stop.

"I can see where [Shenher] got all frustrated and shaking her head too, going: 'I'm working for a department that's supposed to help people and nothing's happening,"' he said.

"Every day now, when I see these police cars go by and it says 'to serve and protect,' I go, what a joke. Who you protecting? Willie Pickton?"

After reading your previous blog and now this one, I became so wrapped up in this story that I had to order the book. 👏👏👏

These are many of my same thoughts I also have about the evil people inflict upon others. The proof is in our leaders.