IS FARTING SEXY? IS VOMIT SACRED? ARE PHOTOS OF NAKED CHILDREN NECESSARILY PORNOGRAPHIC?

Why there's no such thing as politically correct anthropology.

Hey Folks,

Lately, I’ve been reading a lot of anthropology, which involves reading ethnographies.

If you didn’t know, an ethnography is an account of a society written by someone who has lived amongst members of that society, usually for a year or two.

If you’re iffy on what the word ethnography means, exactly, I suggest watching this handy two-minute explainer video.

The reason that I’m studying anthropology is because it contains a vast repository of tried-and-true political ideas. Along the way, however, I come across all kinds of fun facts, some of which I’d like to share with you.

One of the fun parts about reading anthropology is finding out how different cultures assign meaning to different things in very different ways. This can be surprising, and entertaining.

One would think, for instance, that vomit would be universally associated with the emotion of disgust.

Apparently, this is not so. According to an ethnography written of the Kwakiutl people of Vancouver Island, vomit was imbued with surprising significance within their system of meaning.

According to a 1981 essay by Stanley Walens:

For the Kwakiutl, vomit is not a substance of filth. Vomit is to a culture with oral metaphors what semen is to a culture with sexual metaphors: an important category of material existence, a symbol of undifferentiated matter with no identifying features and a total potential for becoming. All the power of vomit is potential, not realized. Vomit is the first stage of causality, the state of existence that precedes order and purpose. All things about to begin the process of becoming—fetuses, corpses, the universe before Transformer changed it—are symbolized by vomit. The act of vomiting is not an act of rejection but a positive act of creation, a necessary step in the process of transformation.

Vomit is the transformed identity of the most precious of spirit gifts— food. All food, even though it may not be regurgitated, becomes vomit at one stage in the digestive process. Food and vomit are complementary aspects of single substance: the bodies of animals transformed into, respectively, cultural and spiritual forms. Vomit is thus the symbol of transformed substance: and the cycle of ingestion, digestion, and regurgitation is a metaphor for the cycle of death, metempsychosis, and rebirth.

Isn’t that fascinating? It really makes you think, doesn’t it? If you happened to be born into Kwakiutl society 200 years ago, you would not necessarily be disgusted by vomit. You might, in fact, think it quite natural to believe that the universe might have been created through the act of vomiting. Nor would such a metaphor necessarily be distasteful to you. Isn’t that a mindfuck?

Part of the fun of reading ethnography is attempting to see one’s own culture through new eyes, to identify aspects of our own culture which could be seen as entirely bizarre when viewed from an outsider’s perspective.

As much as we might feel that our thoughts and desires are our own, we are shaped by our culture in ways that are imperceptible to us.

This is certainly true when it comes to the sexual mores which happen to be current within any given culture at any moment in time.

Many have noted that different European cultures have different characteristic kinks. The English seem to have a predilection for bondage, spanking, and stern discipline. The French seem to take special pleasure in eroticizing Catholic religious tropes. American men love cheerleaders; American women love cowboys. As for the Germans… no comment.

One thing that I never imagined is that there would be an entire culture that would eroticize flatulence, but according to one credible source, there is.

What you are about to read is an excerpt from an ethnography of a nomadic tribe of hunter-gatherers in Bolivia called Nomads of the Long Bow. It was written in the 1940s, so please pardon the politically incorrect language.

Oh yeah, and so long as I’m talking about political correctness, I thought I’d throw in a picture of some naked children just to make a point.

I grew up reading National Geographic, which would often feature pictures of naked or semi-naked indigenous people, and I don’t remember anyone having a problem with that. Do you?

Now, however, I’m actually not sure if it’s even legal for me to post this picture of Siriono tribespeople. This goes to show how quickly attitudes can change.

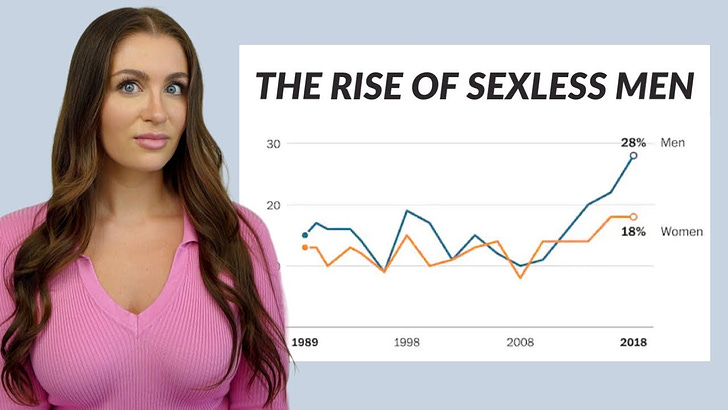

Nowadays, internet pornography is ubiquitous and is silently wreaking havoc on society. Sexual imagery is everywhere, yet we are deep in the midst of the Great Sex Drought.

In many ways, we have much more sexual freedom than our grandparents or great-grandparents did, but do we live in a truly sex-positive society? Are our attitudes towards sex truly healthy? Are people more sexually fulfilled than they were before the internet revolutionized our imaginations?

Personally, I doubt it. What I see is the commodification of sexual imagery serving the interests of a great marketing machine. For most people, sexual liberation remains as elusive as ever.

Fewer and fewer people are having sex. Fewer people are falling in love, forming long-term intimate relationship, or getting married. More marriages are ending in divorce.

Behold, the great irony of the Great Plastic Age - in an age where we have greater sexual freedom than ever before, we are having less sex than ever before.

What would sex-positive sex education look like?

Hey Folks, As you know, I’m very into political anthropology. It’s not just me, by the way. There seems to have been quite a revival in interest in the subject lately, which I take as a sign that people are realizing that our entire civilization is profoundly fucked-up somehow.

What is to be done about this? I don’t claim to know. But one thing that we will have to acknowledge at some point is this:

WE ARE NOT NORMAL.

SEX AND THE LIFE CYCLE

Excerpted from Nomads of the Long Bow by Allan R. Holmberg

The Siriono say of a person in whom sexual desire is aroused that he is ecimbdsi. To be ecimbdsi is all right when sexual activity is confined to intercourse with one’s real spouses, and occasionally with one’s potential spouses, but one who takes flagrant advantage of his sex rights over potential spouses to the neglect of his real spouses is accused of being ecimbdsi in the sense of being promiscuous. Such accusations not infrequently lead to fights and quarrels.

Romantic love is a concept foreign to the Siriono. Sex, like hunger, is a drive to be satisfied. Consequently, it is neither much inhibited by attitudes of modesty and decorum, nor much enhanced by ideals of beauty and charm. The expression seéubi (“I like”) is applied indiscriminately to everything that is enjoyable, whether it be food to eat, a necklace to wear, or a woman to sleep with. There are, of course, certain ideals of erotic bliss, but under conditions of desire, these readily break down, and the Siriono are content to conform to the principle of “any port in a storm.”

In general, men prefer young women to old. In speaking of their sexual affairs, men always express a fondness for a yukwdki (i.e., a girl of about the age of puberty), while they refer with distaste to akondémbi acikwa (literally, “tortoise rump,” i.e. a woman who is old and has a wrinkled rump like that of a tortoise). The preference for youth is also clearly noticeable among the women, who on occasion have intercourse (obviously pleasurable) with their husbands’ younger brothers even before the latter show signs of puberty. Besides being young, a desirable sex partner—especially a woman—should also be fat. She should have big hips, good-sized but firm breasts, and a deposit of fat on her sexual organs. Fat women are referred to by the men with obvious pride as eréN ekida (fat vulva) and are thought to be much more satisfying sexually than thin women, who are summarily dismissed as being ikdNgi (bony). In fact, so desirable is corpulence as a sexual trait that I have frequently heard men make up songs about the merits of a fat vulva. Unfortunately, I was never able to record them.

In addition to the criteria already mentioned, certain other physical signs of erotic beauty are also recognized. A tall person is preferred to a short one; facial features should be regular; eyes should be large. Little attention is paid to the ears, the nose, or the lips, unless they are obviously deformed. Body hair is an undesirable trait and is therefore depilated, although a certain amount of pubic hair is believed to add zest to intercourse. A woman's vulva should be small and fat, while a man’s penis should be as large as possible.

Although love is not idealized in any romantic way by the Siriono, a certain amount of affection does exist between the sexes. This is clearly reflected in the behavior that takes place around the hammock. Couples frequently indulge in such horseplay as scratching and pinching each other on the neck and chest, poking fingers in each other's eyes, and even in making passes at each other’s sexual organs. Lovers also spend hours in grooming one another—extracting lice from their hair or wood ticks from their bodies, and eating them; removing worms and spines from their skin; gluing feathers into their hair; and covering their faces with uruku (Bixa orellana) paint. This behavior often leads up to a sexual bout, especially when conditions for intercourse are favorable.

Sexual advances are generally made by the men, who employ various approaches to obtain their end, depending upon the circumstances existing at the moment. During the day, when there are people around, a man usually whispers his desires to a woman, and the couple steals off into the forest. If a man is out in the forest alone with a woman, however, he may throw her to the ground roughly and take his prize without so much as saying a word. During the night, when the Siriono do not venture out of their hut and when all sex activity takes place in the hammock, a man with desire simply waits until the house quiets down and then wakes up the woman with whom he wishes to have intercourse. At this time, of course, extramarital relations almost never occur.

Much more intercourse takes place in the bush than in the house. The principal reason for this is that privacy is almost impossible to obtain within the hut, where as many as fifty hammocks may be hung in the confined space of five hundred square feet. Moreover, the hammock of a man and his wife hangs not three feet from that of the former’s mother-in-law. Furthermore, young children commonly sleep with the father and mother, so that there may be as many as 4 or 5 people crowded together in a single hammock. In addition to these frustrating circumstances, people are up and down most of the night, quieting children, cooking, eating, urinating, and defecating. All in all, therefore, the conditions for sexual behavior in the house are most unfavorable. Consequently, intercourse is indulged in more often in some secluded nook in the forest.

Between married couples, a good deal of sexual intercourse takes place in the late afternoon in the bush, near the water hole or stream upon which the band is camped. It is rarely indulged in more than once a day. When the afternoon meal has been eaten, and before retiring, couples often proceed to the water hole to bathe and, after bathing, indulge in sexual intercourse. Unmarried couples and potential spouses, of course, must take advantage of whatever opportunities arise. A favorite spot for sexual indulgence between potential spouses, when there is one near the camp, is a patch of ripening maize, which is generally both near at hand and secluded.

The sexual act itself (nyeméno or tiki étiki) is a violent and rapid affair. There are few if any preliminaries. Kissing is unknown, but oral stimulation is not absent; lovers have the habit of biting one another on the neck and chest during the sex act. Moreover, as the emotional intensity of coitus heightens to orgasm, lovers scratch each other on the neck, chest, and forehead, so that they often emerge wounded from the fray. Although people are proud of them, these love scars sometimes cause trouble (in case of extramarital intercourse), because they are visible evidence of the infidelity of a husband or wife.

During coitus in the bush, the woman lies on her back on the ground with her legs spread apart and her knees flexed. The man rests his knees on the ground between her legs; his elbows also rest on the ground on both sides of her body, leaving his hands free for scratching activity. The male plays the most active role during coitus, moving on the woman with considerable force and rapidity. The woman, however, does not remain completely passive, but adjusts herself to the movements of the man.

Emotional pitch is intense during coitus, which is often accompanied by farting, a habit from which considerable pleasure is apparently derived.

When intercourse takes place in the hammock, the positions are essentially the same, but it is more difficult to maneuver because of the added movement of the hammock. Sometimes during the height of the act, a man’s knees slip through the strings of the hammock, and his whole emotional set is disturbed. Informants frequently made jokes about their fellows in this respect. I even knew one man who injured himself rather seriously when his knee struck the ground.

Generally speaking, great freedom is allowed in matters of sex. A man is permitted to have intercourse not only with his own wife or wives but also with her (their) sisters, real and classificatory. Conversely, a woman is allowed to have intercourse not only with her husband but also with his brothers, real and classificatory, and with the husbands and potential husbands of her own and classificatory sisters. Thus, apart from one’s real spouse, there may be as many as eight or ten potential spouses with whom one may have sex relations. There is, moreover, no taboo on sex relations between unmarried potential spouses, provided the women have undergone the rites of maturity. Virginity is not a virtue.

Consequently, unmarried adults rarely, if ever, lack for sexual partners and frequently indulge in sex. In actual practice, sex relations between a man and his own brothers’ wives, and between a woman and her own sisters’ husbands, occur frequently and without censure, but intercourse with potential spouses more distantly related occurs less often and is apt to result in quarrels or lead to divorce.

Food is one of the best lures for obtaining extramarital sex partners. A man often uses game as a means of seducing a potential wife, who otherwise might not yield to his demands. A concrete case will best illustrate the manner in which this is done. Aciba-eéko (Long-arm) had a potential wife, a classificatory cross-cousin, whom he had been trying to seduce for some time without success; she had consistently refused him her favors for fear of provoking a quarrel with her husband. One day, however, when there was little or no meat in camp and the woman’s husband was off on the hunt, Aciba-edko returned with his family from a chase on which he had been absent for several days and on which he had been successful in bagging considerable game, including a peccary which was very fat. His potential wife, being hungry, was most anxious to secure a share of the catch. She waited until Aciba-edko was alone—his wives had gone for palm cabbage and water—and approached him with the following request: “ma nde s6ri tai etima; sedidkwa” (“Give me a peccary leg; I am hungry’).

He replied, “éno, cuki ¢uki airdne” (“O.K., but first sexual intercourse”). She replied, “ti,manédi gadi” (“No, afterward, no less”). He said, “ti, ndmo gadi” (“No, now, no less”), She replied, “eno, maNgitiP” (“O.K., where?”). He answered, “aiiti” (“There”), pointing in the direction of the river. Both of them set out, by different routes, for the river, and returned, also by different routes, the woman carrying firewood, about half an hour later. He secured his prize; she, hers.

Of course, a man is often frustrated in his attempts to secure extramarital intercourse by the methods indicated above. Failures in this respect, however, result not so much from a reluctance on the part of a woman to yield to the desires of a potential husband who will give her game, but more from an unwillingness on the part of the man’s own wife or wives to part with any of the meat that he has acquired, least of all to one of his potential wives. In general, the wife supervises the distribution of meat, so that if any part of her husband’s catch is missing, she suspects him of carrying on an affair on the outside, which is grounds for dispute.

Consequently, men try to pursue their extramarital intrigues as secretly as possible. Instead of attempting to distribute meat to a potential wife after game has already been brought in from the forest, they may send in some small animal or a piece of game to the woman through an intermediary and thus reward her for the favors they have already received or expect to receive in the future. I know of two such instances in which a woman’s brother played the role of messenger, and in a number of cases, I too acted as an agent for two lovers who were having difficulty in carrying out their affair. Fortunately, I was seldom suspected of collusion.

Fights and quarrels over sex are common but occur less often than fights over food. As has already been mentioned, such quarrels arise largely as a result of too frequent intercourse with a potential spouse to the neglect of the actual spouse; this is really what adultery amounts to among the Siriono. However much men are chided by their wives for deceiving them sexually, this seems to have little effect on their behavior, for they are constantly on the alert for a chance to seduce a potential wife with whom they have not had sexual relations or to carry on an affair with a yukwdki (young girl) who has passed through the rites of puberty. In plural marriages, however, I rarely noted pronounced sexual jealousy between the wives, possibly because most plural marriages are of the sororal type.

In all sexual relations, basic incest taboos must be strictly observed. That is to say, it is strictly forbidden to have sexual intercourse with any member of one’s nuclear family, except one’s spouse. Among the Siriono, these incest taboos are generalized to include non-family members who are designated by the same kinship term as those used for members of the nuclear family. Consequently, one may not have sexual relations with a parallel cousin, with the child of a sibling of the same sex, with the child of a parallel cousin of the same sex, with a sister or parallel cousin of the mother, with a brother or parallel cousin of the father, or with the child of anyone whom one calls “potential spouse.” In addition to these taboos, which are clearly reflected in the kinship system, sex relations with the following relatives are also regarded as incestuous: grandparent and grandchild, parent-in-law and child-in-law, uncle and niece, aunt and nephew, a woman and her mother’s brother’s son, and a man and his father’s sister’s daughter.

Violations of incest taboos are believed to be punished by the supernatural sanction of sickness and death. However, I never heard of a case of incest occurring among the Siriono, even in mythology. The reason for this probably lies in the fact that the sex drive is rarely frustrated to such an extent that one is tempted to commit incest.

Atypical sex behavior is also rare. I heard of no cases of rape, i.e., of intercourse with a girl who had not yet undergone the rites of puberty. When a man uses a certain amount of force in seducing a potential spouse who has passed through the rites of puberty, this is not regarded as rape.

Masturbation is likewise not a common juvenile pastime, and I never heard of it being practiced by adults. Children, especially boys, however, finger their genitals a great deal without censure, and when they are young their parents masturbate them frequently. Among the men, the pattern of fingering the penis, especially tugging on the foreskin, carries on into adult life. Since it occurs most frequently when they are standing around, it is probably an automatic reaction to anxiety; when a Siriono is worried, he usually has hold of his penis.

In so far as I could tell, only one man showed any tendency toward homosexuality, but this never reached the point of overt expression. By his fellows, he was regarded more as a woman than as a man. He had never had a wife and spent most of his time with the women. He lived next to his only brother, was regarded as harmless, and made his living largely by collecting and trading some of his products for meat. I was able to get almost no information from or about him.

Only one other case of sexual perversion came to my attention, and this was of a man called Etémi (Lazy). Besides being what his name suggests, Etémi had, according to the women, a sadistic mania for wounding them on the breasts during sexual intercourse. Consequently, they would have nothing to do with him. He had no wife and was most uncommunicative. His favorite pastime—the reason for his nickname—was resting, which he managed to do a great deal of by the following ingenious device. He was an expert at tracking tortoises. He would gather as many as ten of them at a time and hang them up alive on a beam in the house. He would then butcher one or two each day, meanwhile resting in his hammock, until the supply was gone. He spent long periods of time alone in the forest and was one of the few Siriono out of whom I could worm no information whatsoever.

Chastity not being a virtue, there are few occasions when sex is taboo among the Siriono. During menstruation, sex relations are forbidden, but during pregnancy, they are recommended and indulged in up until shortly before delivery. Following childbirth, a woman refrains from intercourse for about a month, but there is no prescribed period after delivery during which she must abstain. Following the death of a spouse, a widow or widower may resume sex relations within a matter of three days. There are, moreover, no other ritual or ceremonial occasions when adults are restricted from participation in sexual activity.