WHAT IS THE SHAMANIC TRACE? (MY MIND IS BLOWN!)

WHAT IS FLUID HISTORY? WHAT IS REVERSION? WHAT IS CULTURAL INVERSION/SCHIZMOGENESIS? WHAT IS EXODUS? WHAT IS ETHNOGENESIS?

The Effigy Mound builders adopted the idea of the mound from Cahokian/Mississippian Civilization, but they changed the entire meaning of the mounds into a symbolic language that transpires both within Nature and about Nature simultaneously.

If it were not for the ravages of time and the Wisconsin dairy industry, we would possess an entire “Koran”, as it were, of “waymarks on the horizons” of Nature—a “Bible” of lessons about the correct relations among humans, animals, plants, and spirits. Most of the “book” is missing and the rest in fragments—but those fragments lie before us openly on the ground.

As “words” in a language of images, each Emblem seems to hold within itself the fractal image of the whole System, the entire emblematic landscape.

If we offer tobacco, and receptive silence, they may still speak.

-Peter Lamborn Wilson

HEY FOLKS,

HOLY FUCK! I just read an incredible book and it was one of them books that makes you go: HOLY FUCK!

The book is called The Shamanic Trace by Peter Lamborn Wilson and technically it’s not even a book. It’s an essay contained within a book called Escape from the 19th century, which was published in 1998.

Now, I don’t know if your average reader would get anywhere near excited as I am about this essay, which is about an indigenous society that built huge mounds in the effigies of different animals, birds, and human figures in what is now Wisconsin.

But it just so happens to be about something that I have been very interested in lately - the idea that the cultural anarchism of indigenous Turtle Islands had been the result of a hard-won battle with an oppressive state centred in a place called Cahokia, which is now St. Louis, Missouri.

THOSE WHO WALK AWAY FROM CAHOKIA (WHAT IS ETHNOGENESIS?)

Hey Gang! As you know, I’m a big believer that anarchist theory is in need of a big overhaul, and I’ve been doing my best to play my part. Lately, I’ve been wondering how many of my readers are actually familiar with post-left anarchist theory. I’m guessing that some of you probably think that post-left anarchism is a new thing, but it is absolutely not.

Basically, there is way more evidence to support the anarchist revolution theory of the Fall of Cahokia than I was previously aware. The history is fascinating!

Wilson goes so far as to suggest that after the Cahokians were defeated, some of them travelled south and became the Aztecs. This makes me wonder whether they might have anything to do with the abandonment of Teotihuacan, which I have never understood.

So, basically, we might eventually be able to agree on the exact location of Aztlan - it seems that it may well have been St. Louis, Missouri. If the author of the classic train-hopping novel Evasion is to be believed, there is a horribly negative terrible energy to East St. Louis to this day. To be fair, though, he was judging it based on the slum next to the train yard. But there was a lot of cannibalism and ritual murder that took place in St. Louis, and apparently it’s still a violent place to this day. Crazy.

But that’s just scratching the surface of what an incredibly mind-blowing book/essay this is.

Peter Lamborn Wilson also presents original evidence and by far the most compelling interpretation of the Effigy Mound Builder culture I had ever heard. He did fieldwork, visiting “about a hundred” mounds and consulting with multiple knowledge Winnebago knowledge keeper, which it seems that no credential archaeology had bothered doing. He seems to have even located a member of an indigenous secret society which preserves the sacred knowledge of that lineage. How mind-blowing is that?

If you didn’t know that there are indigenous secret societies all throughout Turtle Island, now you do!

Wilson then introduces the idea of “the Clastrian machine”, which refers to cultural mechanisms within indigenous society that prevent the emergence of hierarchy. The name is a tribute to Pierre Clastres, an anarchist anthropologist who wrote a classic book called Society against the State, in which he explains how culture acts as a force which prevents the emergence of dominance behaviour.

Some people think that anarchists believe indigenous people were innocent children who never had dominant urges or tyrannical impulses, but those people don’t get it. Hunter-gatherers are people just like us - no better, no worse. It’s just that culture that causes people to behave in certain ways that allow them to live in harmony. And in cultures that have stood the test of time, there’s certain ways of dealing with certain problems, and all cultures have to have ways of dealing with the problem of a tyrannical leader. One of the purposes which a functional culture must serve is that of counter-dominance.

This is very similar to an idea that I got from David Graeber - that of imaginary counterpower. Put together, the two ideas are more than the sum of their parts.

Put it all together, and what have you got? The makings of a whole new way of conceiving of political possibility, along with a set of analytical tools and vast reservoir of theory. It’s a pretty frigging exciting time to be into this stuff!

What is Counter-Dominance?

Hey Gang, Lately, I’ve been on a big anthropology kick. In a recent piece, I announced my intention to introduce some interesting concepts I’ve come across by in my studies. In that piece, I picked ten political terms that I think are valuable and polled my readers about whether they were familiar with them.

In Defence of David Graeber and his Theory of Imaginary Counterpower

David Graeber was a rationalist, democratic, technophilic socialist. He uncritically supported democracy, and was unable or unwilling to accept that it subordinates individuals, he was uncritical of leftist causes (such as feminism) and continually focused his ‘activism’ through statist party politics, he was uncritical of professionalism (firing shots …

THE BEST POLITICAL IDEAS ARE IN ANTHROPOLOGY

I feel like I’ve been wandering around in a desert of ideas and suddenly find that I’m at some kind of all-you-can-eat buffet. It turns out that the ideas were always there waiting to be discovered, but I wasn’t looking in the right place. The right place to look is in anthropology.

When you read Mauss, Clastres, Graeber, and Wilson together, an increasingly clear picture begins to emerge. There are certain things that every culture that wishes to remain one of equals must do, and those can be enumerated and expanded upon.

Then we can look at the different solutions that different cultures have had to those problems and consider what we might be able to learn from them.

And that’s what we should do, if you ask me. We need to figure out where we want to get to before we can figure out how to get from here to there. So we do need a vision, and the vision needs to be compelling. You really shouldn’t go around trying to convince people of things that you don’t yourself believe, so we need to really think things through before we go proposing actual strategies.

As I have said before, my preferred strategy is Cultural Inversion, Exodus, and Ethnogenesis. The goal is to create a permanent counterculture which develops its own ways of meeting its needs outside of the system. The idea of counter-economics, which Derrick Broze promotes, is part of this also.

The Shamanic Trace also introduces the idea of REVERSION, which is another term that I think that we start using.

Reversion is the opposite of progress. It involves returning to an earlier state instead of advancing to a new one. If people were agriculturists, but then abandoned agriculture and took up foraging instead, they are said to have reverted to hunting-gathering. But what if they were slaves? Their reversion, in that case, would be an improvement upon their former state as unfree labourers.

The Myth of Progress casts Forward Momentum in Time as if it were some good in and of itself, but such is not the case. If you took a wrong turn, sometimes the smartest thing you can do is go backwards. When we reimagine collapse, we should reimagine reversion. When we look at the ways different societies are changing now, let’s keep in mind that they could also change back to the way they used to be. Culture does not move unidirectionally.

In the case of the Effigy Mound Builders, it seems that they rejected the hierarchy and brutality of the Cahokian culture. Indeed, many of the mounds are, according to preserved indigenous knowledge, monuments to agreements made between nations. They may be read as monuments to cooperation.

Anyway, really, just read the book/essay. Then read it again. Then let a few years go by and read it again. This is a serious barnburning razzling-dazzler of a book. I’m seriously blown away by this man’s encyclopedic knowledge of world mysticism. It’s bonkers.

This book should be a classic, yet it’s incredibly obscure!

Anyway, I will probably write something about the Clastrian machine eventually, but for, I really just want you to read The Shamanic Trace. It’s a highly significant piece of the puzzle.

Thank you for much to the Immediatism podcast for producing an audio version of this book/essay, which you can find here.

I hope that you enjoy The Shamanic Trace, and don’t forget to leave a comment!

for the wild,

Crow Qu’appelle

The Shamanic Trace

(For the Dreamtime Avocational Archaeology Group)

“In the Big Rock Candy Mountains,

the jails are made of tin,

And you can walk right out again

as soon as you are in.”

—Harry K. McClintock, “The Big Rock Candy Mountain”“Where there is still a people, it does not understand the state and hates it as the evil eye and the sin against customs and rights.”

—Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, I.

1. Birth of a Notion

The emergence of a State seems revolutionary in terms of la longue durée, but appears gradual in terms of human generations. The State emerges slowly, even hesitantly, and never without opposition.

“State” stands for a tendency toward separation and hierarchy. Is “capital” a different force? At the level of custom in the non-authoritarian tribe, the two are not necessarily distinguished. Accumulation of goods, for example, is seen as usurpation of power; the chief in such a case will be virtually powerless because the chiefly function is redistribution (“generosity”), not accumulation.

Where does the State emerge? In Sumer or Egypt? But separation and hierarchy must have already occurred long before the “sudden appearance” (as archaeologists say) of the first ziggurat or pyramid. We should look “back” to the first moment when the durable but fragile structure of the non-authoritarian tribe is shattered by separation and hierarchy. But such a moment leaves no trace in stone or written record. We must reconstruct it on a structural basis making the best use we can of “ethnographic parallels”. We should investigate whether myth and folklore contain “memories” of such a moment.

Now the great contribution of P. Clastres was to point out that no such thing as a “primitive” society exists or ever existed, if we mean a society that is innocent of the knowledge of separation and hierarchy.[6] The problem proposed by Rousseau to the Romantics:—how can one return to innocence?—is a non-problem. The actual situation is much more interesting. The “savages” are neither ignorant nor unspoiled. Every society, if it is a society, must have already considered the problem—the catastrophe—of separation. Humans are not blank slates, to be “spoiled” by some mysterious outside force (—where would it come from? outer space?). Separation is inherent in the very nature of consciousness itself. How could there ever have existed a time when it was unknown, since “to know” is already to separate?

The problem for “primitive” society therefore is to prevent separation from reaching catastrophic proportions and manifesting as hierarchy-eventually as “State” (and/or “Capital”). Normal humans want to preserve autonomy and pleasure for themselves—the whole group—and not give it up to a few. Therefore normal society is defined by rights and customs that actively prevent catastrophic emergence. The question whether any given individual or group is “consciously aware” of the purpose of such structures is far less important than the operative existence of the structures themselves. If “rights” allow for fair redistribution of goods, for example, and “customs” (including normative mythologies) succeed in preventing the accumulation of power, then these structures must be seen as efficient modes of reproducing non-authoritarian society, no matter what “explanation” may be given by the “ethnographic subject” or informant.

Society opposes itself to the “State”:—that is the Clastrian thesis. Its motive is clear and unambiguous, provided we understand the life of the non-authoritarian tribe not as "nasty, brutish and short" but as a process of maximizing autonomy and pleasure for the whole group. This process is closed to separation and hierarchy, so the individual maximizing of pleasure, for instance, is limited by the requirement of a rough equality of condition, and the autonomy of the individual (though it may be extreme) is limited by the autonomy of the group. The hunter/gatherer economy, dependent on small groups in ecological balance with nature, is ideally suited to this non-authoritarian structure. And as Sahlins made clear in Stone Age Economics, the hunter/gatherer economy—even in ecologically disadvantaged areas like deserts, rain forests, and the Arctic—is based on abundance and leisure.[7] (The hunter can know starvation of course-but not “scarcity”—because scarcity is the opposite of surplus or accumulation, and opposites cannot exist without each other.) In Paleolithic times, when humans occupied the richest ecologies of Earth, the hunter’s “subsistence” must have been rather idyllic. No wonder hunting survived well into the era of agriculture under the sign of a kind of magical freedom from work and routine; at one point hunting was supposed to be the privilege of the aristocracy, and resistance to authority took the form of poaching. Even in medieval times the elaborate rules for dressing game can be seen as prolongations of the essential act of the primordial hunter:—the just distribution of the kill. (This is also one of the origins of animal sacrifice.)

The non-authoritarian hunter/gatherer tribe seems to have been the universal form of human society for 99% of its existence. We have legends of lost and prediluvian “civilizations” like Atlantis, but no archaeological evidence for them. Perhaps we should take them seriously, however, as mythic reminders of the fact that separation and hierarchy could have emerged at any point in that longest of long durations we call “prehistory”. Once tools were developed by homo erectus, implying the existence of full consciousness (since tools represent a prosthesis or “doubling” of self), presumably the potential for emergent catastrophe was already complete as well. But it “failed” to emerge. The anti-authoritarian institutions analyzed by Clastres prevented it from emerging.

From a certain point of view agriculture is the one and only “new thing” that has ever happened in the world. We are still living in the Neolithic, and industry (even “information” technology!) is still a prolongation of agricultural technology—or rather agriculture as technology. If we could eat information, we might speak of a “revolution” and an end to the Neolithic. Who knows? it may happen. But it hasn’t happened yet. Civilization itself—the “culture” of cities—our conceptual world—was formed at Çatal Hüyük or Jericho (or somewhere similar) less than 10,000 years ago. Not very impressive in terms of the Long Haul!

Moreover, since Sahlin’s paradigm-shift, a great mystery hovers around the question of agriculture. Namely:—What on earth could induce any sane person to give up hunting and gathering (four hours daily labor or less, 200 or more items in the “larder”, “the original leisure society”, etc.) for the rigors of agriculture (14 or more hours a day, 20 items in the larder, the “work ethic”, etc.)? The “first farmers” had no idea of the glories of Sumer or Harappa to spur them on in their drudgery—and if they could have foreseen such glories, they would’ve dropped their seed-sticks in despair and disgust. Babylon was not destined for peasants to enjoy, after all.

A study of myths and folk tales about the origin of agriculture reveals over and over again that it was the invention of women—a logical extension of womens’ gathering, of course—and that the establishment of agriculture somehow entailed violence to women (sacrifice of a goddess, for example). The link between agriculture and ritual violence is strong. Not that hunters are ignorant of ritual violence (e.g., “primitive warfare”)—not at all. But human sacrifice, head-hunting, and cannibalism, for example, seem to belong much more to agriculturalists (and to “civilization”) than to the hunter/gatherers. Offhand I can’t think of one hunting tribe that practiced such customs—all the cannibals, etc., were “primitive agriculturalists”, or advanced agriculturalists such as “us”, who disguise our human sacrifices (in an “electric chair” no less!) as legal punishments. No doubt exceptions will be found—I simply haven’t read enough anthropology to make any categorical statements—but I will stand by my intuitions about the “cruelty” of agriculture (“raping the body of our Mother Earth”, as hunters often call it). Intense anxiety about the calendar, the seasonal year, which must be adjusted to “fit” the astral year (the image of divine perfection), leads to a view of time itself as “cruel”. The smooth time of the nomadic hunter (unstriated, rhizomatic, like the forests and mountains, like “nature”) is replaced by the grid-work, the cutting of earth into rigid rows, the year into layers, society into sections. “Division of labor” has really emerged; separation has emerged. Hence there must be cruelty. The farmers who work 14 hours a day instead of four are being cruel to themselves; logically then they will be cruel to each other.

The hunter is violent—but the farmer is cruel.

So we might expect to find the moment of emergence of the “State” somehow associated with the “Agricultural Revolution”. For some time after reading Sahlins (and misinterpreting him) I looked for a direct link between the catastrophe of agriculture and the catastrophe of State-and-Capital. But I couldn’t find it. True, separation has occurred. But separation does not appear to lead “all at once” to hierarchy. In fact “primitive” farmers are just as staunchly non-authoritarian as the hunters. Perhaps we need to revive the old idea of a “stage” of horticulture as opposed to agriculture per se. The gardener works hard, but also still hunts, both for meat and for pleasure (and for the sake of preserving an actual and ritual relation with “nature”). Even free peasants are fiercely independent, and horticulturalists are quite “ungovernable”. Hard work is seasonal for the gardener, with plenty of time left for laziness and feasting. The Dyaks, gardeners and headhunters, have an extreme zerowork mentality, and spend as much time as possible lying about drinking and telling stories (see Nine Dyak Nights.[8]) The gardeners’ chief has the most yams or pigs, but is also obliged to beggar himself by giving feasts—his “power” is constantly deconstructing itself in potlatch. Warfare is still “primitive”, in that it still operates to diffuse and centrifugalize power and wealth rather than accumulate it. The war chief is still a temporary appointment; his power ends with the end of war. Custom and right still protect group autonomy, and still prevent the effective emergence of the State. It may still prove to be the case that the State is an epiphenomenon of agriculture; but the key would not lie in the crop-growing process itself. since cultivation of the earth can be carried out without accumulation. The key is the invention of surplus and scarcity. The whole thrust of the “Clastrian machine” (if I can use this term to describe the entire system of rights and customs that resists State-emergence) is not aimed at any economic technique, and in fact can survive even the great transition from hunting to horticulture. It is aimed against the accumulation of wealth and power, which must be resisted by keeping wealth and power in maximum (potential) movement. Accumulation is stasis—stasis is scarcity. Scarcity implies surplus (opposites cannot exist without each other)—and surplus implies appropriation. Agriculture makes surplus possible—but not necessary. The State begins with the breakdown of the “Clastrian machine”.

Fine. But where did it happen? And when, and how? It might be interesting to consider the possibility that it never really happened at all. If we are all still living in the Neolithic, then it must be true that we are all somehow still living in the Paleolithic as well. We still have our immemorial rights and customs (i.e., customs “older than memory”) that preserve for us the remnants of our autonomy and pleasure. These fragments are not “lost” but perhaps severely reduced in scope and scale, limited to secret corners and cracks where the monolithic power of State-and-Capital cannot penetrate. I believe this to be the case in a sense, and this paper will be devoted to tracing those rights and customs as they appear out of prehistory, so to speak, and enter into history, and persist. History itself can be viewed as a process of Enclosure, a fencing-in and reduction of the area ruled by “custom” in our sense of the word (which we owe to E. P. Thompson).[9]

Yet this process remains (by definition?) incomplete. Autonomy and pleasure have failed to disappear; the rule of State and Capital depends in part on a spectacular delusion, and pretense of the erasure of customs. And even when autonomy does disappear, it is sustained by a kind of secret tradition, rooted in the Paleolithic, that guarantees its re-appearance. (Again: the “tradition” need not be conscious to be “real”.) The “Clastrian machine” never breaks down—entirely.

Nevertheless, something happened! We have the evidence at Uruk. I saw evidence myself at Aztalan in Wisconsin, the site of the farthest-north extension of the Mississippian or Cahokian culture of pre-Columbian North America, where agricultural city dwellers killed and ate hundreds of human beings (some archaeologists speak of the “Southern Death Cult”). The ziggurats, mounds, and pyramids reveal the very structure of these catastrophic societies:—hierarchy has burst its ancient bonds, freed itself of the restraints of “right and custom”, and triumphed over a beaten class of peasants and slaves. The strictures of the old tribal laws and myths of equality and abundance and against separation and hierarchy have proven so weak as to seem non-existent, never existent. State and/or Capital has triumphed. Autonomy and pleasure have become property.

We may never be able to track down the “moment” of the State. But one thing we can be sure of:—it didn’t just happen, on its own, spontaneously, and according to some law of evolution. No climate change or population growth pushed an innocent and unresisting mass of humans into History. Humans were involved. The State (as G. Landauer said) is a human relation, a relation amongst humans and within humans.[10] It is always possible. But so is resistance.

In a sense the State can be seen as a revolt against the old rights and customs. We cannot call it the revolt of a “class” because non-authoritarian societies have no classes. But it does have roles, functions, divisions. Hunter/gatherer, men/women, chiefs/people, shamans/non-shamans. One or more of these divisions must have revolted against the others. If the shamans revolted we would expect the emergence of a “priestly” State; if the chiefs or warriors, a “kingly” State; if the women, a “matriarchy”—and so forth. Unfortunately we can find examples of all these, and mixtures as well. An analysis of primitive institutions cannot provide us with an answer, because each of these institutions in itself is designed to prevent the State, not to facilitate it. As Blake would say, each of these institutions possesses its emanation or form and its spectre; the former holds the latter in check. The revolt we’re looking for would be a spectral emergence, therefore, and thus perhaps impossible to see.

In order to throw light on this problem we need two things: a more complete definition of the “Clastrian machine” (Clastres himself dealt mostly with primitive warfare); and a number of examples of how it works not only in “primitive” societies but also and especially in “historical” societies, where it operates as opposition to separation and hierarchy. Once we can view the mechanism more clearly perhaps we can “read it back” and see where catastrophe would be most likely to occur. Of course we must avoid any “mechanistic” interpretations—our “machine” is organic, complex, even chaotic. But some generalizations may prove feasible, even so. Our hope lies in the continuity of the institutions in question, their “traditions”, their cohesion toward meaning. Rather than seeing “rights and customs” merely as Paleolithic survivals or extrusions of non-authoritarian mores into a later and more developed authoritarian totality, we should see them as representing the consideration of catastrophe that society has always already made, and that resists all corrosion despite its infinite mutations, regressions, compromises, and defeats—a consciousness that persists, and finds expression.

In order to define more clearly the “Clastrian machine”, then, we need to name its parts—which, for the sake of brevity, we will limit to three: “primitive warfare”, the “Society of the Gift”, and shamanism. We might examine any customs of non-authoritarian peoples in the expectation that all of them will harmonize (however indirectly) with the double function of realizing autonomy and pleasure and suppressing separation and hierarchy. But these three areas of custom are directly concerned with the social economy or dialectic we want to examine. Do we have a problem of categorization here, in trying to compare three such “separate spheres” under the rubric of some apparently unified or universal force? But Society itself has already done so:—it combines war, economy, and spirituality within its “universe”. Admittedly the world of ethnographic discourse is not a clearly-bounded pure and impermeable abstraction; nevertheless we would be unable to sociologize or anthropologize to any extent whatsoever if we could not assume that a given society experiences itself on certain levels as a whole. We have located the “Clastrian machine” on such a level; our demonstration will depend on comparing our examples according to this hypothesis. In order to suggest the persistence of the “machine” through history we shall have to expand our search beyond the “perfect case” of the non-authoritarian hunter/gatherer or horticulturalist tribe (which in any case exists for most of us only in ethnography, archaeology, folklore, etc.); we need to examine cases from eras in which Society is losing or has already lost power to the State (and/or Capital), and in which the “machine” now acts as an oppositional force, or for the facilitation of autonomous zones within the space of Power.

2. Machinations

According to Clastres, “primitive” warfare and “classical” warfare are radically different phenomena. Warfare as we know it, from Sun Tzu to Clausewitz, is waged on behalf of separation, appropriation, hierarchy, accumulation of power. In this sense we are still waging classical war, despite its supposed apotheosis into the “purity” of instantaneity and cyber-spectacle (“information war”). For us, warfare is centripetal, drawing power towards the center. Primitive war, however, is centrifugal—it causes power to flee the center. First, warriors have no (political) power except on the warpath. Second, war is considered an affair of personal glory (“immortal fame”), not a means of acquiring property, slaves, or land. The rare prisoner is either killed or adopted into the tribe; there is no “surplus of labor”. Third, in fact, and most importantly, any booty must be shared out with the whole tribe—the warrior acquires nothing for himself alone, nor does the warband enrich itself as a sodality at the tribe’s expense. Fourth, actual death is rather rare in such war; there is no “excess manpower” to spare. Honorable wounds (or even symbolic wounds, as in “counting coup” among the Plains Indians in North America) and clever thefts are more highly valued than martyrdoms. But the primitive warrior soon comes to understand that a life devoted to war can end only in a glorious death, or in a miserable old age of poverty and powerlessness-since the tribe is very careful to see that he accumulates neither wealth nor authority.[11] Hence the well-known “melancholy” of the primitive warrior, so often noted in the literature. The “uncleanness” of the warrior, frequently expressed in ritual and myth, represents the anxiety about his role shared by the tribe as a whole. If the warrior revolts against tribal custom and seizes power and wealth for himself (an obvious temptation), he has committed what G. Dumezil called “the sin of the warrior”[12]—in effect, the creation of “classical warfare”.

Thus for Clastres primitive warfare was the perfect model of rights and customs institutionalized as a force for the dissipation and centrifugality of power as separation. Primitive war serves precisely the purpose of Society in resisting the emergence of the State. It is not really “primitive” in the sense of being a crude and imperfect foreshadowing of classical war; in fact, it is a highly sophisticated complex evolved for distinct “political” purposes. Violence, which appears as a “natural” human trait, must not be allowed to cause separation within the tribe. Violence must be used to protect and express the egalitarian structure of the non-authoritarian group, not to threaten it. Violence is the price of freedom, as the 18th century revolutionaries might have expressed it—but not of appropriation and slavery.

The idea of the Economy of the Gift as a “stage” in social development was clarified by M. Mauss and refined by G. Bataille and others.[13] Here it would be misleading to speak of “primitive exchange” or “primitive communism”, since it is not a matter of property-in-movement or property-in-common but of the failure of property to emerge. The potlatch of the Northwest Amerindian tribes, as we know it from ethnographic literature, is perhaps not the ideal model for elucidating the “Gift”; its “classical” form of “conspicuous consumption” is now seen as perhaps owing too much to pressure from an encroaching money-economy to be considered as an organic expression of the economy of reciprocity. Potlatch in this form might better be considered in the light of Bataille’s “Excess”—the necessity for non-exchange in a society of “primitive abundance”. The original “pre-Contact” form of potlatch would perhaps have included a wider system of smaller but more numerous and frequent ceremonies, in which the essentially redistributive nature of potlatch might be seen more clearly. If we accept an historical development from the economy of the Gift to the economy of redistribution to the society of exchange, then potlatch would belong to the second “stage”, not the first. And this would make ethnographic sense, since the Tlingit, Haida, and other tribes were in fact highly civilized town-dwellers with authoritarian chieftaincies, hereditary usages, division of labor, monumental architecture, etc.—more comparable to Çatal Hüyük or even pre-Dynastic Egypt than to, say, the Inuit, Australian Aborigines, rain forest pygmies, or even “primitive” horticulturalists. The true economy of the Gift is to be found among such non-authoritarian peoples. It originates in the equal sharing-out of game and gathered food, and is anything but arbitrary or “spontaneous”. Every person has a “right” to the Gift, and knows exactly what will constitute reciprocity. But nothing “enforces” the Gift except “rights and customs” (and the possibility of recourse to violence). The Gift is “sacred”—and generosity is “divine”—because the very structure of the social depends utterly and absolutely on the free movement of the Gift. The Gift in turn is related to the Sacrifice, in which the spirits that provided the game (and who in effect are the game) are included in the kinship structure of the tribe by the gift of a portion of the kill (usually blood or smoke) in return for the gift of life’s very sustenance. This structure also holds for plants and the “lesser mysteries” of gathering—which will evolve into the grand sacrificial ideology of the Neolithic. The Gift is the voluntary sacrifice that “atones” for the violence of the hunt or the cruelty of agriculture, and "at-ones" the fabric of society by including everything (animals, plants, the dead, the living, the unseen) in symbolic unity and renewal. Property fails to appear in such a society because everything that might be property is already Gift; the possibility of exclusive possession has been pre-empted by usage and by donation, or donativeness, to coin a term.

In reality however, the three “stages of economic development”—gift, redistribution, and exchange—cannot be seen as a crude linearity or conceptual grid or diachronic fatality. Each is overlaid, super-inscribed, contaminated, magnetized, and compromised with the others in a palimpsestic permeability of cross-definitions, paradoxes, and dialectical violence. The economy of the Gift is also obviously an economy of redistribution and exchange, in broad general terms. We somewhat arbitrarily reserve the term redistribution to refer to the chiefs (and later the States) in their function as ritual conduit of wealth for the people—it flows to the “top” and is redistributed “justly” and as widely as possible. As we’ve seen, in some tribes this means the chiefs are periodically bankrupted by the custom of excessive generosity they must honor—and even the “classical Civilizations” of Sumer, the Indus Valley, Egypt, or the Mayans experienced ceilings or upper limits on their power of accumulation, due to the ancient rights and customs of redistributive justice. In a sense, then, the structure of redistribution is a prolongation of certain aspects (or “survivals”) of the structure of the Gift; the Gift is still embedded in the economy that now overcomes or (at least) absorbs it. The imperative of redistributive justice, to which even the most despotic of despots must pay lip service, if not true devotion, consists in fact of the “Clastrian machine” at work within the authoritarian structure of the ancient kingships and theocracies. Not even king or priest must interfere with this justice, which is (therefore) cosmic in nature—an eternal truth—a morality.

Now the mystery of the third stage of economic development—“exchange”—as K. Polanyi pointed out[14] —is its failure to appear. In the ideal terms of Classical Economics, exchange was always the purpose and telos of any “earlier” or “more primitive” economic form. Property was inherent in these forms as the flower in the seed, and only needed to “evolve” toward the dawn of “the Market” eventually to be born as full-fledged 19th century Capital. The assumption is that all societies are based on greed and competition, but that we moderns have at last realized a rational system to maximize the positive (wealth-generating) aspects of this eternal law of nature while suppressing the negative aspects by legislation. But Polanyi, as an economic anthropologist, was able to prove that no known human society ever based itself or its economy on the presumption of greed and competition as laws of nature. On the contrary, the economics of the Gift and of Redistribution are based on a deliberate refusal of such a possibility. They represent the “Clastrian machine” at work against the emergence of “pure exchange”, which has always already been foreseen and suppressed by the Social for itself and in itself. The one and only social system based on “exchange” is that of 18th and 19th century European capitalists and their class-allies among the intelligentsia. Even in the 20th century, the “Market” still failed to emerge, thanks to the redistributive ideologies of Roosevelt, Hitler, and Stalin—who for all their evil still paid lip service to the immemorial ideal of economic justice. In fact “exchange” really only emerges in 1989 with the collapse of the movement of the Social, already hopelessly betrayed by its own leaders and thinkers. For the first time in history, the Market today rules unopposed. Or so it believes. In fact, of course, the “earlier” economies of Gift and redistribution are still present “under” the inscriptions and prescriptions of the Capital State. They cannot be erased, and they cannot be considered as “failed precursors” to the triumphalist Market. If they have been forced underground into a “shadow economy” of barter, “black work”, fluid cash and alternative forms of money, etc., they nonetheless persist and find expression. The totality of Capital remains illusory—and in fact has its true being in “virtuality” and “simulation”. The very completeness of its victory, which seems to culminate a long, drawn-out process of gradual encroachment, evertightening enclosure, and relentless erosion of “empirical freedoms”, presents Capital all at once with the question posed to it by its very universality.

This question could perhaps best be expressed in terms of money.

Symbolic exchange already exists within the economy of the Gift. Malinowski’s Pacific Argonauts, who trade splendid but useless works of ritual art over thousands of miles of open sea, practiced a closed system in which symbols could only be exchanged for symbols, not for “real wealth”. In fact the process was a kind of Bataillesque Excess, not a form of money. The extremely important but little-studied trade in ceremonial polished-stone axe-heads that pervaded all of late Paleolithic and early Neolithic Eurasia and Africa, may offer another example. Earlier axe-heads tend to be full-sized and utilitarian, while later ones move toward delicacy, miniaturization, and aesthetic perfection. The axe-heads had an obvious spiritual value for numerous and wide-spread cultures, ranging from Neanderthal to Minoan Crete. It’s interesting to note that an early form of Chinese coinage took the shape of small axe-heads. It’s possible that the Paleolithic axe-heads were not merely traded for other symbolic goods, but also for “real wealth”, in which case they could be considered “money”. If so, however, it must have been a money hedged around with taboos in order to prevent its becoming an opening to separation and hierarchy through “primitive accumulation”, because we have no evidence that the ceremonial axe-heads changed society the way money changes society. No doubt these objects took their place in a complex system based on reciprocity rather than the “profit motive”!

A most persuasive argument was made by the German scholar Bernhard Laum and his followers, who assert that the origin of money is in the Sacrifice.[15] Each part of the animal in venery and in sacrifice has its designated recipient as gift. Incidentally this constitutes a kind of pecking order, a potential form of separation that must be “rectified” by the concept of rights and customs. This rectification holds good within the intimacy of the hunting band or horticultural village-but when the group becomes too large to share in a single sacrifice (for example, in a typical agricultural Neolithic town of 500 or so), then tokens must be distributed among the whole group, while the sacrifice itself is reserved to the “priests” (a custom that survives into Greece and Judea, of course). These tokens eventually take the shape of “temple souvenirs”, which are later traded (because they have “numinous value” or mana) for real wealth. Hence the first coins, from 7th century Be Asia Minor, are issued by temples, stamped with numinous symbols, and made of symbolic metal (electrum, a mixture of solar gold and lunar silver). The idea of money as numismatic numina explains how money will be able to reproduce itself even though it is not alive (money is the sexuality of the dead). When "money begets money", the old rectified egalitarianism of the sacrifice is shattered by the possibility of accumulation and appropriation (“usury”). Religion has in a sense inadvertently let loose the demon of money in the world, which explains religion’s ambiguous relation to the stuff. For religion, all exchange is usury—and yet religion is the very fountainhead of money itself. Jesus of Nazareth, for example, is said to have felt this paradox with particular poignancy.

The temple-token theory of money’s origin is instructive but not conclusive—since in fact money makes a much earlier appearance—(somewhere in the proto-Sumerian millennia of the mid-to-late Neolithic)—as pure debt. Its pre-history can be traced in the rubbish-heaps and tells of archaeological digs in the Near East, in the form of clay tokens representing units of material wealth (we can guess this because some of them have the obvious shapes of hides, animals, containers, plants, etc.). Later on one finds clay envelopes containing sets of clay tokens, with symbols of the tokens pressed into the clay to record the envelope’s contents. At some point around 3100 BC in Uruk, some clever accountants realized that if you have symbols of tokens on the outside of the envelope you don’t need actual tokens inside the envelope. You can manage much more easily with a clay tablet impressed with symbols. Thus writing was invented.[16]

Now the clay tokens can only have been symbols of exchange—but obviously not money in the way coins are money. They were records of debt. It’s easy to see that the token-system developed along with the Temple cult, since the tokens are found in or near Temple storehouses. We can guess that the primitive tokens represent promises to pay, and we can surmise that the Temple was the focus of accumulation and redistribution for the whole community. We can presume this because the earliest cuneiform tablets that can be deciphered seem to show such a system (or State!) already long established and taken for granted. There are promises to pay the Temple, and there are “cheques” issued by the Temple—in effect, “money”. Once again we see money emerging from a religious matrix.

Money can be defined as a symbolic medium of exchange—although on the basis of the “sacrificial” origin-theory it might be more accurate to call money a medium of symbolic exchange. In Sumer however these perhaps complementary definitions can be subsumed into a much older and deeper definition:—money is debt. As soon as debt begins to circulate, credit appears—since opposites cannot exist without each other. Your debt is my credit, just as your scarcity is my surplus, and your powerlessness is my power. Just as mana once seemed to adhere to the temple souvenir and made it more valuable than the “cost” of the useless symbolic metals that composed it, so also “wealth” now seems to adhere to money itself, even to mere paper, despite the fact that the “medium” is strictly imaginary (a consensus-hallucination), and that the “wealth” in question is nothing but debt, “promise to pay”, sheer absence. The anarchist P.-J. Proudhon once hypothesized that money must have been invented by “Labor”—the poor—as a clever means of forcing primitive accumulation into motion, so that some wealth might flow at least as “wages”.[17] lt’s an intriguing notion, because it reveals that money in interest-free and immediate circulation—“innocent” money, so to speak-can appear as a form of empirical freedom. But Proudhon was wrong about the origin of money, if not about a certain aspect of its fate. Money originates and emerges in history as debt. But it has a “pre-history” as appropriation. The egalitarian economy of the Gift—which does not know money—can be shattered only by the economy of surplus and scarcity. Now these terms can have meaning only for human beings:—some few will enjoy surplus, the rest must experience scarcity. Slavery, tribute, and debt are all forms of scarcity. Without writing and even without arithmetic, sophisticated systems of surplus/scarcity accounting are quite possible—but writing succeeds not merely in accounting but in representing surplus and scarcity, a form of control that appears as “magical” because it emanates from the Temple, and because it effects action-at-a-distance. At this point the Temple became a Bank, a moment that can still be traced in the architectural details of modern banks-and at the same time, it became a bureaucracy (or perhaps we should say the bureaucracy, since all bureaucracy is somehow the same bureaucracy).

Money is still today heavily inscribed (almost “overdetermined”) with religious and heraldic symbolism, an obvious clue to its true “origin”. But once the idea of money is born into the world (with writing as midwife, not mother), the link between money and writing can be broken. Anything can be money provided people believe it to be money:—cows, cowrie shells, huge stones, gold dust, salt. All that need be grasped is the notion of representation-the notion of separating wealth from the symbol of wealth and then simultaneously (and “magically”) recombining them as “money”. This kind of separation and paradoxical thinking can only be achieved by a society already split by separation and hierarchy, surplus and scarcity. Money does not create the State, though it may serve to mark the border between a “primitive State” and the full-fledged genuine article,[18] In clashes between a money economy and a non-money economy (say between Europeans and Natives in 16th century America), money itself inevitably acts as an opening wedge into the psyche of the infected people, since it bears with it all the “interest” that animates the society of separation. The Cargo Cults serve as modern-day examples of this process, as do millenarian cults with the opposite objective of refusing money and “White Man’s goods”,[19] Money reveals its true nature in such borderland situations where it comes into conflict with gift economies and non-authoritarian tribes, or even with quite sophisticated (but essentially moneyless) civilizations such as the Aztecs, Incas and Mayans. The “Clastrian Machine” goes into overdrive in an attempt to ward off catastrophe not from within its own society but from outside it. Both the beautiful ideals of the millenarians and their violence are attempts to construct a theory and praxis of resistance out of a “way of life” that had always already considered the catastrophe of its breakdown into separation and hierarchy. Once the economy of the Gift is destroyed and then even its memory is effaced (except in folklore and custom), resistance must take other forms. But the ideals, secretly enshrined in tradition, never die out entirely. They may come to take quite bizarre and superstitious forms, fragmentary, unconscious, ineffable—but they persist. Peasant revolts, bread riots, the cloud-cuckoo-lands of mad heretics and rebels, forest outlaws and poachers-thus for example did the primordial tradition of resistance find expression in medieval Europe.[20] The ideal of reciprocity, and (failing that) the ideal of redistribution, can never be entirely effaced and replaced by the idea of exchange. The very moment of the apparent triumph of the Market—of exchange—will inevitably call forth the old, old dialectic once again (like the phoenix reborn from its ashes)—and the re-appearance of the cause of the Gift.

Like primitive warfare and the economy of reciprocity, shamanism is a part of the “Clastrian machine” and an almost-inevitable feature of hunting and gardening societies. (Obviously I’m using the word “shamanism” quite loosely.) The important thing to note about the shaman is that he or she is not a priest. The line of demarcation may grow quite fuzzy, but on either side of the line one can discern quite distinct realities. The priest serves separation and hierarchy and the shaman does not. The shaman is not paid a salary and is not a “specialist”, does not necessarily receive a “line of succession” from teachers, and does not "worship God".[21] The shaman must hunt or keep a garden like anyone else. In many tribes, “everyone shamanizes” to some extent, and “the” shaman is simply a first-among-equals, not at all comparable to a modern “specialist”. Initiation for the shaman may or may not be mediated by other shamans, but inevitably it consists of direct unmediated contact with spirits or “gods”. No succession is involved, and no faith. The shaman does not look on “worship” as a one-way street, or as debt to be paid; the shaman works with the spirits and even compels them. Great shamans are even greater than great spirits. Even so, the shaman has no “authority” except that of the successful practitioner. In many tribes a shaman who fails too often (or even once!) may be killed. Shamans may be chiefs or warriors or advisors to chiefs and warriors, but in the end possess no more political power than chiefs or warriors. In non-authoritarian society everyone shamanizes a bit, and is also a bit of a chief and a warrior—even the women and children (who have mysteries and sodalities of their own, and perhaps also voices in the assembly). Thus although shamanism as an institution fulfills Durkheimian functions of social cohesion, it also serves as a dissipative or centrifugal force in relation to accumulation of power. Most significantly, the shaman does not represent the spirits but makes them present (either with entheogenic plants, or by becoming possessed, or by the “trickery” of sucking out witch-objects, etc.). Spirits that are present are experienced by “everyone”, not just by the shaman. The priest by contrast may no longer be capable even of an exclusive “experience” of presence, much less able to facilitate it for his entire congregation. Among the Huichol of Mexico only the shamans see and communicate with the “Great Spirits” while eating peyote but everyone else on the Pilgrimage also eats peyote, and witnesses the shaman communicating with the Spirits. But with or without entheogens, shamanism is experiential and therefore “democratic” (or rather, rhizomatic)—while priestcraft is based on mediation and faith, and is therefore separative and hieratic.

The shaman is directed by the “Clastrian machine”, so to speak, inasmuch as he or she is prevented from acquiring unjust accumulations of power—but the shaman also directs the machine, inasmuch as the spirits always vote for the supremacy of “rights and customs” that guarantee or at least safeguard autonomy for society. It’s interesting to consider the shamans as not only the visionaries of their societies but also as the intellectuals. They “think with” plants, animals and spirits rather than with philosophies and ideologies. Shamans are “outsiders” in many ways and yet they occupy a kind of “center” of their societies, a focal-point of social self- and co-definition. In societies of separation the intelligentsia are “insiders” (priests, scribes) but displaced, out of focus, and finally powerless.

Thus we have named at least three parts of the complex of rights and customs that expressed Society against the State—war, economics, and spirituality. They are a unified entity inasmuch as society itself is “one”, first in its opposition to the emergence of the State, and then (later) in its resistance against the hegemony of the State. In the former case, their unity is effective; in the second case, it is shattered and even fragmented—but still on some level a recognizable whole. For instance, even the classical and modern societies still harbor “survivals” of reciprocity and redistribution, or shamanic experience, or violence as a defense of autonomy. But even in such fragmented conditions there persists a deeper “substructure” in which a living connectedness among these parts can be experienced. For example, on one level war, reciprocity, and spirituality all have to do with death and the Dead, and with the relation between the Dead and the Living. Since classical and modern social paradigms cannot “speak to the condition” of the Dead with the same directness and unity as the “ancient ways”, we still live with vestiges, shreds, hints, and unconscious apprehensions of those old ways—we still live “in” the Paleolithic.

It seems that only in some relation with the primordial “rights and customs” can we hope to resist the totality of separation and strive for the degree of autonomy and pleasure our imaginations can encompass. Of course the paradigm of hierarchy has long ago proven itself adept in the appropriation of opposition; it makes shamans into priests, chiefs into kings, warriors into an instrument of oppression; and the spectrum of human potential it transmutes into caste and class. But once all the old roles have seemingly been appropriated, somehow they re-appear outside the bounds of control or even definition. Shamanic talents crop up in salesmen and housewives (especially after the re-emergence of ceremonial entheogenism in the 1960s); non-authoritarian structures suddenly appear within institutions:—the “facilitator” and the “talking stick” replace Robert’s Rules of Order. The courage of the warrior deserts the hi-tech battlefield and manifests in gangs of young criminals; and the old slogan of the peasant revolts—“Land and Liberty!”—refuses to go away.

My contention is that the “Clastrian machine” goes on manifesting itself long after its original non-authoritarian social matrix has been destroyed and seemingly lost in the amnesiac obsessions of “History”. Writing, which serves power, has only deepened the amnesia with its deliberate lies and its perpetuation of stupidities. History as writing must be circumvented and evaded in order to come at the truth.

What truth? For example: that the “nomadic war machine” subverts the very centripetality of classical war, and is always veering off into chaos. That there are whole economies that know nothing of money or exchange (economies of emotion, of language, of sensation, of desire). That there exists an unbroken underground tradition of spiritual resistance, a kind of hermetic “left” that has roots in Stone Age shamanism, and flowers in the heresies of the “Free Spirit”. We must now turn to tracking the traces of that spirit—the “Clastrian machine”—through the tangled thickets of historiography, ethnography, -graphia itself.

3. Wild Man

In the search for exemplary cases I will focus on shamanism more than on warfare or economics. All institutions of right and custom can be visualized as pillars holding up the edifice of non-authoritarian society; and even when the house is in ruins, reduced to the slums or margins of Civilization, the unity of the original structure can still be discerned. Of all the pillars, however, shamanism claims for itself a certain centrality:—axis mundi, in effect—conceptual focus of the whole social construction. And even in the decay and ruination of the Social, shamanic “remnants” still appear in axial positions in the geographic or conceptual spaces of exile, dispossession, and depletion. In other words, as the field of rights and customs is gradually enclosed, the spirit of resistance “loses its body” and is deprived of its geographical, tactical, and economic materiality, till only "spirit" remains. A defeated or enslaved people will be reduced to tales and memories of former glory; till one day the people, spurred by those memories, rise to re-embody them in material resistance. And as shamanism is precisely that which pertains to spirit (ésprit), we must look to shamanism, or to its fragmented survivals, or even to its “trace”, in order to see the continuity of the “Clastrian machine” in History.

Hélène Clastres (wife of P. Clastres) has provided us with vital epistemological tools for our search in her Land-Without-Evil, a study of the mysterious mass migrations of the Tupi-Guarani of South America in search of an earthly utopia, the “Land-without-Evil”.[22] Urged on by visionary shamans, the tribes would wander off after signs and wonders, abandoning their fields and villages in defiance of the chiefs and elders, and often come to grief through starvation or enslavement by another tribe, or be turned back by impassable mountains or oceans. H. Clastres shows that these remarkable movements began well before any contact with Europe, and in fact took another form in the post-Contact era. Originally it appears that the migrations occurred as a result of a struggle between the shamans and the chiefs. Perhaps under the distant and indirect influence of the Incas or other High Civilizations, the chiefs were asserting more and more power within the tribes, upsetting the egalitarian and non-authoritarian structures of Tupi-Guarani society. The migrations involved leaving agriculture behind and “reverting” to hunting and gathering. The new nomadic way of life, which was far from normal for these people, was interpreted by the shamans as a shamanic quest involving the entire people, not just the shamans.

Chiefly power was disestablished simply by walking away from the chiefs. The Land-without-Evil was an image of the tribe as it should be and once was, according to proper right and custom. If the strategy failed because the Land-without-Evil could not be found (since it was an ideological construct and not a real place) , nevertheless the shamans succeeded for brief periods in revivifying the old autonomy and inspiring the people with visionary fervor. The quests occurred over and over again for generations and were still going on when the repercussions of the Conquest were beginning to be felt. Gradually the migrations assumed a new form in response to these different forces, and began to resemble the sort of millenarian movements familiar to the student of the colonial process. Shamans and others emerged as military leaders, and “primitive warfare” was added to shamanic power in uprisings and rebellions—all doomed to fail. The “Clastrian machine”, already out of balance in pre-Contact times, struggled against dissolution with drastic means, even with a kind of mass suicide—but against the money-economy and technology (and germs) of the Europeans these “embodied” forms of resistance were simply crushed.

But shamanism was not erased by colonization in South America—in fact, it has renewed itself again and again, and still persists today. Indeed, it may even be experiencing something of a renaissance. To understand how shamanism continues to serve as (at least) a conceptual space of resistance, even after “Contact” with monotheism and capitalism, we may turn for instruction to M. Taussig’s brilliant study of ayahuasca healing cults, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man.[23] On the one hand, Taussig points out, the conquerors always regard the conquered (the “natives”) as radical Other, despised sub-humans, devoid of culture, better off dead, etc., etc. This is the daylight or conscious side of colonialist “racism”, so to speak. But it has a night side as well—because, on the other hand, the natives retain some advantages that the conquerors would rather not think about too clearly, lest their superiority should begin to appear to them as less than absolute. For instance, the conquerors are strangers in a strange land, but the natives are at home. They are “wild men”, but this implies a connection with locality that the colonialist cannot share. They know where to find animals and plants-often the early colonists would starve unless the natives fed them, and this momentary dependence still rankles in the collective memory of the colonial gentry [e.g., “Thanksgiving” as a festival of guilt in North America]. Above all the native knows the spirit of place and possesses a magic that appears uncanny, ambiguous, or even dangerous to the colonist—depending on degree of credulity, in part, but also on a general background of Christian imagery, fear of the unknown, and the genuine bad health of the colonists. Sooner or later the conquerors come to believe that for certain afflictions only the Natives possess a remedy. Catholicism, which is already open to “superstition” at the popular level, is perhaps more open to such influences than Protestantism. New England Puritans were not known to consult Algonkin medicine-men, but in South America such situations could arise more easily. In the case of the Ayahuasca cults, the natives possessed a distinct advantage in their knowledge of an “efficacious sacrament” in the form of an entheogenic plant mixture used in shamanic healing. Structurally and to some degree actually the cults pertain neither to the world of the pure-blood colonists nor the pure-blood forest Indians, but to the mixed-blood Mestizos who belong to both worlds and to neither, who are both a bridge and a chasm between cultures. But the axis of the cults, so to speak, tips toward the Forest, and traces itself to aboriginal shamanism. Here it is the Colonists who are outsiders—and yet the Colonists are among the enthusiastic patrons of the healing cults. (And nowadays the expanding Ayahuasca religions like Unio Vegetal are made up almost entirely of “Whites”.) The fact is that shamanism has effected a curious reversal of colonial energies, in which elite anxiety gradually turns into a kind of romanticism (“noble savages”, etc.) and then into an actual dependence on “native” sources of power. Perhaps no one thinks of this situation as “revolutionary”—and certainly Ayahuasca shamanism can do little to disestablish actual elite power—but it must be seen as a kind of mask for subtle forms of resistance.

Taussig’s thesis represents a major break-through in the consideration of shamanism as a system interacting with the whole world, and not as a “pristine”, remote, exotic, and self-enclosed object of analysis without any relevance outside the sphere of anthropology or the history of religions. In short, he has given us a politique of shamanism to match in importance Clastres’ politique of primitive warfare. The model of the hidden power of the oppressed, which is so frequently a shamanic power, prepares us to perceive even subtle models in which the overt signs of shamanism and resistance may be muted almost to the point of invisibility. In fact, since Taussig makes creative use of W. Benjamin in constructing his thesis, we might borrow and adapt Benjamin’s phrase “the utopian trace” and speak of a shamanic trace that may be present even in institutions or images lacking all open connection with shamanism per se. In the ayahuasca cults the links with "pristine" shamanism (assuming it exists as other than a structural model) are quite clear. But in other examples we might examine, the “trace” will be obscured to the point of unconsciousness, just as the trace of "utopia" is obscured by the advertisement in which it is embedded as an image of promise. The difference between utopian trace and shamanic trace is that the former is often deliberately “put into” the advertisement in order to exacerbate commodity fetishism by raising unconscious hopes that cannot be fulfilled; whereas the latter intrudes itself in certain phenomena, so to speak, as an unconscious welling-up or manifestation of “direct experience”. This authentic or valid or veridical experience is the keynote and sine qua non of shamanic reappearance. In this sense the shamanic trace is also “utopian”, since it may involve the desire for such experience rather than the experience itself The desire may take “perverse” forms but even at its most attenuated we can still recognize it as a movement of the “Clastrian machine”, and as a sign that autonomy and pleasure still claim their right and custom.

Shamanism, History, and the State, a collection of essays edited by N. Thomas and C. Humphrey, is dedicated to Taussig and is largely devoted to exploring the opening he has made to shamanism as a “political” form.[24] On the back of the book a statement by Taussig himself appears, speaking of the ways in which “it shows 'shamanism' to be a multifarious and continually changing 'dialogue' or interaction with specific, local contexts. . . . This collection tries to demonstrate through 'case studies' just how different 'shamanism' becomes if seen through a lens sensitive to the history and the influence of institutions, such as the state, which seem far removed from it.” In the whole of this excellent volume, however, there is not one mention ofthe work of P. Clastres or H. Clastres. I cannot imagine why this should be so, unless perhaps a certain post-Marxist slant of the Taussig “school” has prejudiced it against Clastres, who was an anarchist, and polemicized against Marxist anthropology. Perhaps mistakenly, it seems to me that Taussig’s findings (and those of his "school") are complementary to those of Clastres. What Clastres demonstrated is that "primitive" society constructs for itself a “machine” (my term) to resist the emergence of the State. Taussig shows that one part of this machine, shamanism, goes on resisting the State even after the appearance and apparent triumph of separation and hierarchy. Shamanism, History and the State clarifies Taussig’s work in a number of ways. For example, Peter Gow in “River People: Shamanism and History in Western Amazonia,” examines certain ayahuasca healing cults (not the same ones discussed by Taussig) and finds that although they proclaim themselves to have originated with Forest Indians, in fact they were spread historically by Mestizos and geographically by the Christian missions and the rubber industry in the late 19th century. These cults too belong not to “the Forest” in reality but to the periphery or border between town and wilderness—and not so much to some “pristine” paganism as to resistance against official Christianity. It seems to me that Gow has nicely illustrated both Taussig’s thesis and Clastres’ thesis. On one hand the cults represent a turning-back or even a “reversion” (however romantic and unrealizable) to more primordial customs; on the other hand they represent a “going-forth”, a resistance, a demand for rights.

In an attempt to harmonize the two schools, we should look for examples that have not been treated by either, and attempt analyses based on both. The first theme I want to examine is “reversion”, and the example I’ve chosen has never (so far as I know) been discussed by anyone.

4. Emblematick Mounds

The idea of “reversion” is in the air, anthropologically speaking. In brief, the conviction is growing that many supposedly pristine examples of “primitive” societies studied by ethnographers may in fact be drop-outs from History—that is, they may have reverted to a more primitive state from a more “advanced” one at some point (usually unknown). In an evolutionist view of society this reversion must appear unnatural or perverse: why would anyone give up the benefits of, say, agriculture and revert to hunting and gathering? Or the benefits of rational monotheism for backward shamanic cults? Obviously such reversionary peoples must be inferior, unless they simply had no choice in the matter. But this old progressivist view is no longer so popular. The new orthodoxy implies that because of reversion all “primitivity” is suspect. The pristine ethnographic subject does not exist as an object of cognition. The neo-conservative version of this orthodoxy goes on, therefore, to critique all positive evaluations of “primitive” as mere romanticism or special pleading. The views of such anthropologists as Sahlins and Clastres are under attack as out-moded 60s hippie hot air. There are no “primitives” at all, much less “good” primitives. Any enthusiasm about the original leisure society, the economy of the Gift, or shamanic spirituality, is only a leftist illusion covering up the real reality of “eternal Market values” and the preordained triumph of technology, etc., etc.

A great deal of this new orthodoxy depends on certain presuppositions it makes about “reversion”. The old evolutionist prejudice is still at work, to the point where reversion can be seen as a nullification of all meaning. The word “reversion” is used to end a discourse that it should instead inaugurate. In Clastrian terms, reversion can be interpreted as a victory against the emergence of “higher” forms of separation and hierarchy.

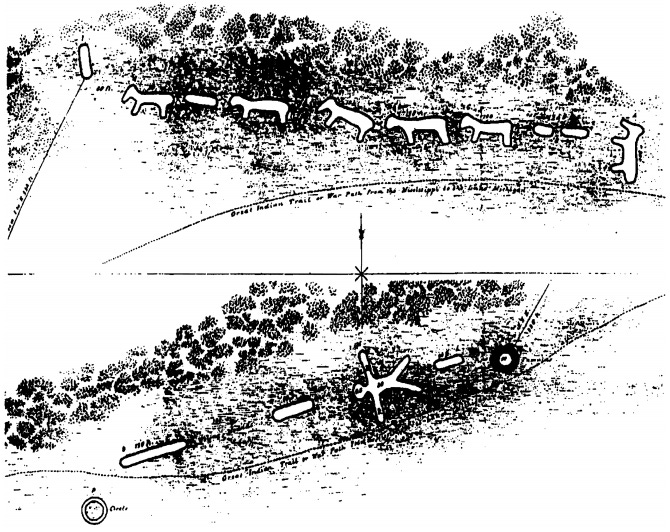

To illustrate this contention I must first begin by describing the Effigy Mounds of Wisconsin. The following section consists of a number of quotations from my own unpublished field-notes, based on two summers (1993-94) during which I saw perhaps a hundred of these mounds.[25]

The “Driftless Region” consists of a large chunk of Southern Wisconsin, with slivers in Iowa, Minnesota and Illinois. It’s called the “driftless” because during the last Ice Age (ironically known as the “Wisconsin Glaciation” since it was first studied by geologists in the northern part of the state) , the glaciers passed around this region, encircling it but not touching it, so that the earth was not flattened and stretched as in the rest of the northern part of the continent, but retained its primordial pre-Pleistocene form, gradually eroding into a landscape of “hidden valleys” and low hills, a mixture of prairie and climax forest. This region coincides precisely with the area in which the effigy mounds are found. The whole eastern half of North America is littered with mounds of various kinds, but most of them are architectural (temples, forts) or funerary tumuli. Effigy Mounds, by contrast, are built in shapes, mostly of birds or animals but also of humans and objects; they are very obviously neither military nor architectural, and only about half of them contain burials. Because they are so different from all other prehistoric American mounds, they remain baffling, mysterious, and even a little bit embarrassing to orthodox archaeology. As a result, they remain almost unknown outside the Drifcless region itself—no glossy coffee table books, no prestigious museum exhibits; they are ignored even by most afficionados of “Mysterious America”, UFOlogy, pre-Columbian contact theories, and the like. Since the 19th century, almost no interpretations of the Effigy Mounds have been propounded, either by archaeologists or occultists. In effect, the mounds have not yet “appeared” except as curiosities in a few state parks, or as the subject of a few obscure academic monographs.

This non-appearance of the mounds constitutes one of their great mysteries. Why are they not seen? Leaving aside the problem of interpretation, the immediate and most striking aspect of the mounds is their great beauty. Considered simply as “earth art” they assume at once a timeless and exquisite power; and the more one sees of them the more one realizes (despite the ravages of time, of agriculture, of archaeology, and of sheer wanton destruction, which have erased perhaps 80-90% of the mounds) that the entire Driftless region is a work of art, a worked geomantic landscape in which wilderness and culture have achieved a dialectical unity and aesthetic/spiritual cohesion. What does it all mean?—an interesting question—but not the essential question. First and foremost, the “meaning” of the mounds is not mysterious at all, but rather completely transparent:—the total enchantment of the landscape. This is not to say that the mound builders were “artists” in the modern sense—“mere artists”—or that the mounds have no other significance than the aesthetic impact of their actual physical presence. Indeed, if we consider the totality of the Effigy Mound “project” as a single art work, or as the transformation of the Driftless region itself into art, we must admit that aesthetics alone could not have animated such a vast vision. Spirituality, economics, and the “social” must have acted synergistically to create the “religion” or way of the Effigies, an entire culture (lasting from about 750 to 1800 AD) centered on mound creation as its primary expression.

As soon as we begin to investigate this culture with the epistemological tools of archaeology, however, the “mystery” of the Effigy Mounds deepens rather than dissipates—and this helps to explain the batffled silence or dull muttering of the academics in the face of such strange evidence. The Effigy Mound culture was preceded, surrounded, invaded, and superseded by “advanced” societies which practiced agriculture, metallurgy, warfare and social hierarchy, and yet the Effigy Mound culture rejected all of these. It apparently “reverted” to hunting/gathering; its archaeological remains offer no evidence of social violence or class structure; it largely refused the use of metal; and it apparently did all these things consciously and by choice. It deliberately refused the “death cult”, human sacrifice, cannibalism, warfare, kingship, aristocracy, and “high culture” of the Adena, Hopewell, and Temple Mound traditions which surrounded it in time and space. It chose an economy/technology which (according to the prejudices of social evolution and “progress”) represents a step backward in human development. It took this step, apparently, because it considered this the right thing to do.

“Ghost Eagle Nest”, Muscoda, surveyed 1886 by T.H. Lewis, re-surveyed 1993 by Jan Beaver, James P. Scherz, and the Wisconsin Winnebago Nation. Note Calumet pipe mound at lower right.

“Man Mound” near Baraboo, original etching and 1989 survey showing damage.

Above: Bear mounds at Iowa National Effigy Mounds Park.

Below: Monuments surveyed by Squier and Davis, 1848, no longer extant

Most archaeologists lose interest in Effigy Mound culture as soon as they realize this “reversion”. As grave robbers, they are disappointed by the poor or non-existent “grave goods” of the Effigy Mounds; and as civilized scientists, they are shocked and offended by the deliberate “primitivism” of a society that seems to have turned its back on the blessings of agriculture, architecture, work and war.

Since the 1960s, however, concepts have developed within anthropology which offer new epistemological tools for the interpretation of prehistoric archaeology. Marshall Sahlins, in his masterpiece Stone Age Economics, presented the first revisionist defense of hunter/gatherer societies as economies of excess (as opposed to the imposed scarcity of agricultural economics) and of immense “leisure” (as opposed to the endless work of the peasant). In the light of such an “anarchist epistemology” (to quote P. Feyerabend), we can now interpret hunter/gatherer cultures in the light of an actual resistance to social hierarchy and the emergence of “The State”. This dialectic was traced by the brilliant French post-Structuralist anthropologist P. Clastres in his classic Society Against the State, and in his unfinished (posthumous) essay on “primitive” warfare, The Archeology of Violence. The point made by Sahlins, Clastres, et at. is that Hunter/Gatherer societies know very well what “progress” implies for the victims of progress (as opposed to the winners, the priest-kings and their house-slaves)—and they reject it by means of their very social organization. Hunters know, for example, how to limit population to ecologically appropriate numbers, and they institutionalize this knowledge. Later the knowledge is deliberately suppressed by agriculturist “nobles” who desire more and more shit-workers and peasants to support them. Agriculture is not the result of any “population explosion”—it is the cause.

The Effigy Mounds apparently have something to say (that is, to show rather than to tell) about the proper technique for humans to relate to “Nature”, to the wild(er)ness, to the “Beauty Way”, as some Native Americans put it—the way of harmony and guardianship. As one sees more and more of the mounds, the initial appreciation of them as "art" broadens and deepens into more subtle and complex categories-not only aesthetic but also spiritual and even “political”. As these levels unfold, the “mystery” only intensifies, of course—and eventually evades all categorization.

The earliest commentators were so impressed by the Mounds of America that they invented an entire “mysterious race of Mound Builders” to account for them—people who couldn’t be Indians—because how could the wicked degenerate Indians have created such great monuments? This racist hogwash has long since been dissipated. Whoever the Builders were or weren’t they were certainly “Indians”, and the Effigy builders were clearly ancestors of such tribes as the Winnebago. But why did they build? What do the mounds mean? All this remains a mystery-so much so that almost no serious interpretive work has been done on the mounds—as if they constituted an embarassment to “Science”! (Is “Science” easily embarrassed? Well, I’ve seen no mention in any archaeological text of the very obvious phallic mounds. And at the Effigy Mounds National Monument Park Museum in Iowa we saw an astounding tablet carved out of red pipestone, the so-called “New Albin Tablet”, which has apparently never been published-because it depicts a shaman with an erection! (See page 97) This work is vital for our thesis—but scientific prudery has placed it on a high shelf, out of the view of children, and even adults have to stand on tip-toe to see it.)