WHY "WHAT IS MONEY?" IS NOT THE ULTIMATE QUESTION

INTRODUCING AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORY OF VALUE

Hey Folks,

Not too long ago, Whitney Webb appeared on podcast called “What is Money?”

I hadn’t heard of the show before, but the host did a great job of interviewing her. He also name-dropped James C. Scott, which is always a good sign. My interest was piqued.

Fast-forward a bit and I was doing some research on Bitcoin, because I was thinking of coming out as a Bitcoin Maximalist and I wanted to make sure I’d crossed my t’s and dotted my i’s.

I came across the following video, which boldly states that “What is Money?” is “The Most Question in the World Today.”

I immediately disagreed, of course. It’s an important question, sure, and I’m happy that so many people are trying to figure out the global financial system works, but surely there are things more important than money. Have people not noticed that it’s the fucking apocalypse?

This really got me thinking. If “What is Money?” isn’t the most important question in the world today, then what is? What is it that we’re really trying to understand? The life, the universe, and everything? Then why are we talking about money?

It also got me thinking. I’m a big believer that it you can’t define a word, you shouldn’t use it. So what is money?

The easy anarchist answer would be: “Whatever the people with the most guns and gold say it is.”

As Chairman Mao said: “Political power grows out the barrel of a gun.” And the golden rule of politics is “He who has the gold rules”.

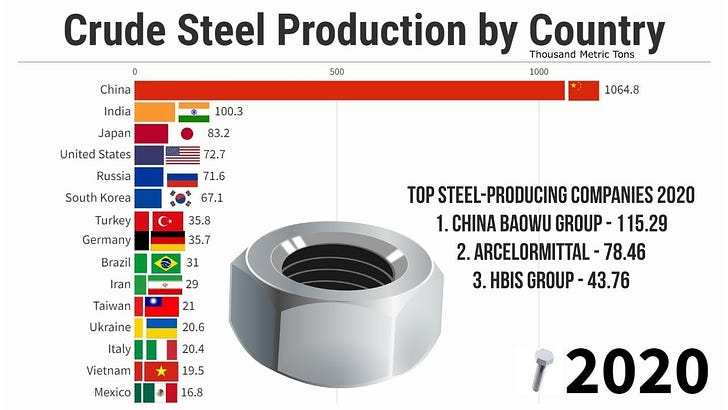

Incidentally, this quickly led to a major insight for me: the Chinese Communist Party now rules the world.

HAIL TO THE RED DAWN!

Hey Folks, Today I am thinking about the triumph of good over evil, because it is Easter. I’m also thinking about the impending collapse of the Zionist-Anglo-American World Empire. It’s obviously immanent. But it seems to me that just about everyone is in denial about it.

They’ve been employing the tried-and-true traditional Chinese strategy for dealing with belligerent foreigners: flood them with riches until they’re soft and flabby, then take over once they’re not longer a threat to you.

Why do we need Money?

But I still felt that “What is Money?” wasn’t the real question. Technically, money’s just a balance sheet of circulating debt. It’s a medium of exchange that you use to pay for goods and services. It’s also a store of value.

But socially, it’s far more than that. Money is the system by which we are ruled. The need for money is one of the defining features of modern civilization. If you don’t have money for food, you’ll go hungry. If you don’t have money to pay rent, someone with a gun will eventually show up and evict you from your home.

As a friend once said, “Money isn’t everything. Not having it is.”

Yet anatomically modern humans have existed for somewhere between 200 and 300 thousand years. For 99%+ of the time we’ve existed as a species, we didn’t need money. So what the fuck happened?

If you tell someone that money only exists because people are brainwashed to accept a scarcity mentality, they’ll probably roll their eyes and tell you to get real. Everyone knows that you need money to live in the modern world, but why?

Well, it’s obvious, isn’t it? Because you need to pay for things you need, like food and a house to live.

But why can’t you just grow your own food, build your own house, and live off-grid in some kind of community where you exchange goods and services amongst yourselves without any bank-issued currency?

Oh yeah, because you need money to buy land building supplies, not to mention building permits, taxes, insurance, and on and on and on. You literally do need money to live in Canada or the U.S. Even the Amish need money, if only to pay tax.

How in the world did things come to this?

This is why anarchists should engage with the question of “What is Money?” Because asking that question will lead the serious thinker to an inescapable conclusion: We are ruled by a gang of crooks.

As Proudhon put it:

To be ruled is to be kept an eye on, inspected, spied on, regulated, indoctrinated, sermonized, listed and checked off, estimated, appraised, censured, ordered about by creatures without knowledge and without virtues. To be ruled is at every operation, transaction, movement, to be noted, registered, counted, priced, admonished, prevented, reformed, redressed, corrected.

If Money is a Store of Value, then What is Value?

Whether we like it or not, this is the world we live in. Unfortunately, most people accept it. We were all taught from a young age to accept this as normal. Children are easy to brainwash.

Most people do not see money as a total system of control, they see as a “store of value” and a “medium of exchange”, and they are indeed both of those things.

If you trade your labour for wages, you can exchange those wages for goods and services. Pretty simple.

But if money is a store of value, then what is value? And if it wasn’t for money, then how would we acquire the good and services we can’t produce for ourselves?

There we go. I think that’s the real question we’re trying to ask.

THERE WAS A TIME BEFORE MONEY AND THERE WILL BE A TIME AFTER MONEY

People value money because they can use it to get things they want. In everyday life, it is a reliable way to get what you what. If you’re hungry, you can go to a restaurant, pay for a meal, and thereby satiate your hunger. Money is a reliable way to satisfy many desires. I like having money a lot better than being broke. If you don’t like having money, it’s probably because you’ve got too much.

Furthermore, when you go to an ATM to take out money, it always gives you the right amount. It’s pretty amazing, actually. What other technology works 100% of the time?

It honestly seems magical, and arguably it is. If magic just means “action at a distance”, it’s undeniably magical. But one also cannot avoid the suspicion that it is evil. After all, it seems to have a special affinity for the worst kinds of crooks imaginable, such as arms manufacturers, bankers, con artists, and pushers of addictive drugs. How could such people have won our trust?

As everyone who has studied crypto now understands, money is ultimately imaginary. It works because people believe in it, sure, but the fact remains that it works. How? Bank are some of the most evil institutions on the planet, yet we trust them with our life’s savings. Why? Is money just straight up sorcery?

Before we dive in, I’d like to ask you to watch the first forty seconds of this video, because it contains a bunch of crypto enthusiasts giving their answers to the question “What is Money?”

They include:

“I think that, if I really had to be specific… I think my best answer would be: it’s a balance sheet.”

“Money… If it’s doing its job, we’re completely unaware of it.”

“Essentially, money is a denominator that everyone uses as a currency, a common frame of reference.”

“We exchange money so we each agree where we’re going to put our attention.”

“My personal, like, thinking is that money is information.”

“Money is just a tool, and tools are instruments that save us time.”

“The meaning that you pronounce upon money is the verdict that you pronounce upon your life.”

So… it’s, like, everything or something?

How did people live before money?

Whitney Webb had by far the best take: “Money is a human invention. But humans existed before money.”

So what did people do before money was invented?

That is the subject that this essay will answer. It is mostly on David Graeber’s Toward An Anthropological Theory of Value, but I’ll add a few thoughts of my own.

I think that this might be one of the most important things I have ever written, as it builds upon the questions that I raised in An Anarchist Theory of Evolution.

I have chosen to make this post available to paid subscribers for a week or so before releasing to everyone.

This will give you some time to think about your own answer to the question “What is Money?”

I know I just made a joke at the expense of the “What is Money?” podcast, but I assure you that it is very much worth your time to listen to.

I suggest starting with the first episode, which features Michael Saylor, the world’s foremost Bitcoin maximalist.

I had certainly heard of Michael Saylor before, but I had no idea what a deep thinker he is. Whether you’re a fan of crypto, he’s definitely worth listening to.

I would also recommend checking out Vitalik Buterin’s explanation of money, which is admirably simple and easy to understand.

As of the current moment, the best single-sentence definition of money I’ve seen is still Elon Musk’s:

“Money, in my view, is essentially an information system for labor allocation, so it has no power in and of itself; it's like a database for guiding people as to what they should do.”

I’ll add my own, though:

“An elaborate system of disguised extortion characterized by a centralized ledger of circulating debt obligations, ultimately backed up by the threat of violence.”

WHY I AM NOT NOT A MAXIMALIST

Hey Folks, As you may be aware, the Bitcoin halving will be this month. I’m hoping that it will be happen on 4/20. If it does, I’m going to take that as a sign.

TOWARD AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORY OF VALUE

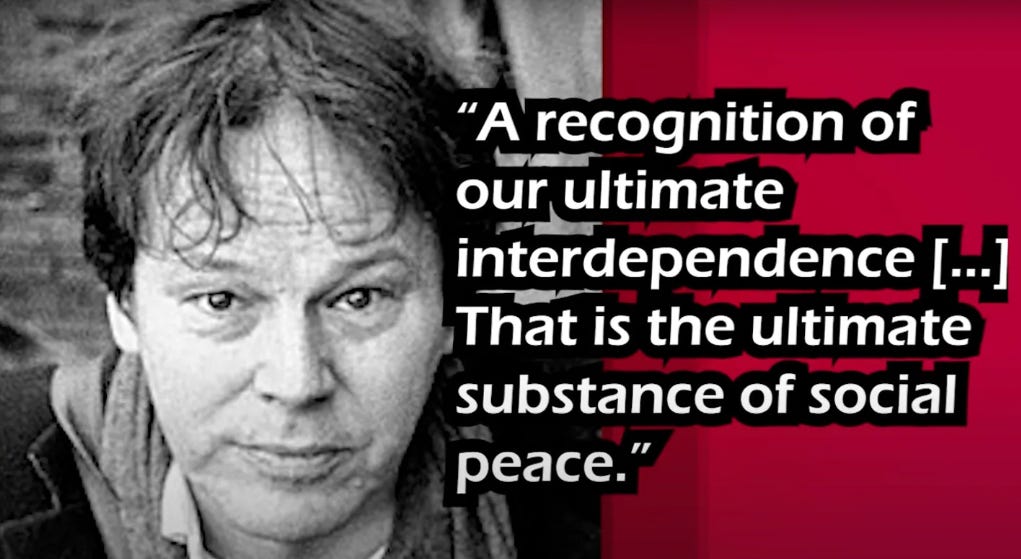

David Graeber was the greatest anarchist economist of all time.

He is best known for his magnum opus Debt: The First Five Thousand Years, the anarchist answer to The Wealth of Nations and Das Kapital.

In that book, he shows how:

Debt is the most efficient means ever created to take relations that are fundamentally based on violence and violent inequality and make them seem right and proper.

Debt: The First Five Thousand Years revolutionized the field of economics, and created ripples around the world.

Indeed, it is widely believed that the Bank of England actually adopted aspects of his analysis. I know this sounds crazy, but apparently they didn’t know what money was either. Bankers have been lying about it for so long that they had forgotten what the truth was.

Despite the fact that money is very literally circulating debt, no one had ever written a history of debt before.

How insane is that?

Debt: The First Five Thousand Years was the culmination of an intellectual project that David Graeber had begun a decade earlier in a much lesser-known book called Toward An Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams.

In the introduction to that book, Graeber explains that:

Many anthropologists have long felt we really should have a theory of value: that is, one that seeks to move from understanding how different cultures define the world in radically different ways (which anthropologists have always been good at describing) to how, at the same time, they define what is beautiful, or worthwhile, or important about it. To see how meaning, one might say, turns into desire.

It is worth noting that Graeber was the latest avatar of an intellectual lineage which can be traced back into an unbroken succession to the founders of sociology and ethnology.

His mentor was Marshall Sahlins, author of Stone Age Economics and The Original Affluent Society, the latter went on to help found anarcho-primitivism.

Sahlins was a student of the brilliant Claude Levi-Strauss, perhaps the most famous anthropologist of all time, as was Pierre Clastres, author of Society Against the State.

Claude Levi-Strauss was the student of Marcel Mauss, the founder of French ethnology and the author of Essay on the Gift, one of the most influential essays in the history of anthropology.

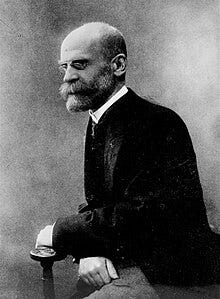

Marcel Mauss was the nephew of Emile Durkheim, who established the academic discipline of sociology. He was hugely influential in his day and is often compared to Max Weber and Karl Marx in the breadth and depth of his political thought.

The False Coin of Our Own Dreams, which was written in 2002, begins by assessing the then-current state of anthropological theory, which Graeber believed had become stagnant sometime about two decades earlier.

The standard history—the sort of thing a journalist would take as self-evident fact—is that the last decades of the twentieth century were a time when the American left largely retreated to universities and graduate departments, spinning out increasingly arcane radical meta-theory, deconstructing everything in sight, as all around them, the rest of the world became increasingly conservative. As a broad caricature, I suppose this is not entirely inaccurate.

He then summarizes assumptions which were then widely accepted in academia:

We now live in a Postmodern Age. The world has changed; no one is responsible, it simply happened as a result of inexorable processes; neither can we do anything about it, but we must simply adopt ourselves to new conditions.

One result of our postmodern condition is that schemes to change the world or human society through collective political action are no longer viable. Everything is broken up and fragmented; anyway, such schemes will inevitably either prove impossible, or produce totalitarian nightmares.

While this might seem to leave little room for human agency in history, one need not despair completely. Legitimate political action can take place, provided it is on a personal level: through the fashioning of subversive identities, forms of creative consumption, and the like. Such action is itself political and potentially liberatory.

He then goes on to compare this narrative to that of “globalization”, which he considers a euphemism for neoliberalism, the system of global debt peonage overseen by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

We now live in the age of the Global Market. The world has changed; no one is responsible, it simply happened as the result of inexorable processes; neither can we do anything about it, but we must simply adopt ourselves to new conditions.

One result is that schemes aiming to change society through collective political action are no longer viable. Dreams of revolution have been proven impossible or, worse, bound to produce totalitarian nightmares; even any idea of changing society through electoral politics must now be abandoned in the name of “competitiveness.”

If this might seem to leave little room for democracy, one need not despair: market behavior, and particularly individual consumption decisions, are democracy; indeed, they are all the democracy we’ll ever really need.

There is, of course, one enormous difference between the two arguments. The central claim of those who celebrated postmodernism is that we have entered a world in which all totalizing systems—science, humanity, nation, truth, and so forth—have all been shattered; in which there are no longer any grand mechanisms for stitching together a world now broken into incommensurable fragments.

One can no longer even imagine that there could be a single standard of value by which to measure things. The neoliberals on the other hand are singing the praises of a global market that is, in fact, the single greatest and most monolithic system of measurement ever created, a totalizing system that would subordinate everything—every object, every piece of land, every human capacity or relationship—on the planet to a single standard of value.

He concludes:

It is becoming increasingly obvious that what those who celebrated postmodernism were describing was in large part simply the effects of this universal market system, which, like any totalizing system of value, tends to throw all others into doubt and disarray. The remarkable thing is that they failed to notice this fact. How?

To put it bluntly: now that it has become obvious that “structural forces” alone are not likely to themselves produce something we particularly like, we are left with the prospect of coming up with some actual alternatives.

[I]f one is looking for alternatives to what might be called the philosophy of neoliberalism, its most basic assumptions about the human condition, then a theory of value would not be a bad place to start. If we are not, in fact, calculating individuals trying to accumulate the maximum possible quantities of power, pleasure, and material wealth, then what, precisely, are we?

He continues:

If one reads a lot of anthropology, one sees references to “value” and “theories of value” all the time—usually thrown out in such a way as to suggest there is a vast and probably very complicated literature lying behind them. If one tries to track this literature down, however, one quickly runs into problems. In fact it is extremely difficult to find a systematic “theory of value” anywhere in the recent literature.

There are, one might say, three large streams of thought that converge in the present term.

These are:

“values” in the sociological sense: conceptions of what is ultimately good, proper, or desirable in human life

“value” in the economic sense: the degree to which objects are desired, particularly, as measured by how much others are willing to give up to get them

“value” in the linguistic sense, which goes back to the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure (1966), and might be most simply glossed as “meaningful difference”

When anthropologists nowadays speak of “value”—particularly, when they refer to “value” in the singular when one writing twenty years ago would have spoken of “values” in the plural—they are at the very least implying that the fact that all these things should be called by the same word is no coincidence. That ultimately, these are all refractions of the same thing.

He then points out that this might seem counter-intuitive, even absurd.

A skeptic might reply: it may well be that all these concepts do have something in common, but if so, that “something” would have to be so utterly abstract and vague that pointing it out is simply meaningless.

He then insists that the three meanings really cannot be separated.

If one looks back over the history of anthropological thought on each of the three sorts of value mentioned above one finds that in almost every case, scholars trying to come up with a coherent theory of any one of them have ended up falling into terrible problems for lack of sufficient consideration of the other ones.

WHAT ARE VALUES?

One can pick up a work of anthropology from almost any period and, if one flips through long enough, be almost certain to find at least one or two casual references to “values.” But anthropologists rarely made much of an effort to define it, let alone to make the analysis of values a part of anthropological theory. The one great exception was during the late 1940s and early ‘50s, when Clyde Kluckhohn and a team of allied scholars at Harvard embarked on a major effort to place the issue of values at the center of anthropology. Kluckhohn’s project, in fact, was to redefine anthropology itself as the comparative study of values.

Nowadays, the project is mainly remembered because it managed to find its way into Talcott Parson’s General Theory of Action, meant as a kind of entente cordiale between sociology, anthropology, and psychology, which divided up the study of human behavior between them.

Psychologists were to investigate the structure of the individual personality, sociologists studied social relations, and anthropologists were to deal with the way both were mediated by culture, which comes down largely to how values become esconced in symbols and meanings.

WHAT IS SOCIALLY DESIRABLE?

So what, precisely, are values? Kluckhohn kept refining his definitions. The central assumption though was that values are “conceptions of the desirable”—conceptions which play some sort of role in influencing the choices people make between different possible courses of action. The key term here is “desirable.”

The desirable refers not simply to what people actually want—in practice, people want all sorts of things. Values are ideas about what they ought to want. They are the criteria by which people judge which desires they consider legitimate and worthwhile and which they do not. Values, then, are ideas if not necessarily about the meaning of life, then at least about what one could justifiably want from it. The problem though comes with the second half of the definition: Kluckhohn also insisted that these were not just abstract philosophies of life but ideas that had direct effects on people’s actual behavior. The problem was to determine how.

In order to compare such concepts, Kluckhohn and his disciples ended up having to create a second, less abstract level of what he called “value orientations.” These were “assumptions about the ends and purposes of human existence,” the nature of knowledge, “what human beings have a right to expect from each other and the gods, about what constitutes fulfillment and frustration”.

In other words, value orientations mixed ideas of the desirable with assumptions about the nature of the world in which one had to act.

The next step was to establish a basic list of existential questions, that presumably every culture had to answer in some way: are human beings good or evil? Should their relations with nature be based on harmony, mastery, or subjugation? Should one’s ultimate loyalties be to oneself, to a larger group, or to other individuals?

Kluckhohn did come up with such a list; but he and his students found it very difficult to move from this super-refined level to the more mundane details of why people prefer to grow potatoes rather than rice or prefer to marry their cross-cousins—the sort of everyday matters with which anthropologists normally concern themselves.

Graeber then notes that Kluckhohn’s project is now seen as a failure, noting that:

Kluckhohn himself seems to have spent the last years of his life plagued by a sense of frustration, an inability to find the breakthrough that would make a real, systematic comparative study of values possible.

He laments this fact, explaining that:

Where British anthropologists had always conceived their discipline as a branch of sociology, the North American school founded by Franz Boas had drawn on German culture theory to compare societies not primarily as ways of organizing relations between people but equally, as structures of thought and feeling. The assumption was always that there was, at the core of a culture, certain key patterns or symbols or themes that held everything together and that couldn’t be reduced to pure individual psychology; the problem, to define precisely what this was and how one could get at it.

One is left with a strange, rather contradictory picture, since this was also the time when Boasian anthropology was at the height of its popular influence and academic authority, flush with Cold War money, at a time when their books were often read by ordinary Americans, but at the same time, was burdened with a growing feeling of intellectual bankruptcy. Kluckhohn’s effort to reframe anthropology as the study of values could be seen as a last-ditch effort to salvage the Boasian project; it is nowadays seen as yet another dead end.

The mention of “Cold War money” is extremely telling, and solid evidence that Graeber was a closet conspiracy theorist.

In his 2015 book The Utopia of Rules, written after he became famous, Graeber is willing to be more explicit:

Sociologists like Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils were deeply embedded in the Cold War establishment at Harvard, and the stripped-down version of Weber they created was quickly stripped down even further and adopted by State Department functionaries and the World Bank as “development theory,” and actively promoted as an alternative to Marxist historical materialism in the battleground states of the Global South.

[Clifford] Geertz was a student of Clyde Kluckhohn, who was not only “an important conduit for CIA area studies funds” (Ross, 1998) but had contributed the section on anthropology to Parsons and Shils’s famous Weberian manifesto for the social sciences, Toward a General Theory of Action (1951). Kluckhohn connected Geertz to MIT’s Center for International Studies, then directed by the former CIA Director of Economic Research…

At that time, even anthropologists like Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, and Clifford Geertz had no compunctions against cooperating closely with the military-intelligence apparatus, or even the CIA.

KLUCKHOHN’S COMPARATIVE STUDY OF HUMAN VALUES WAS ULTIMATELY ABANDONED

The consensus of those who even bother to talk about the episode, though, is that there was nothing inherently wrong with the project itself: rather, it failed for the lack of an adequate theory of structure. Kluckhohn wanted to compare systems of ideas, but he had no theoretical model of how ideas fitted together as systems…

Be this as it may, the project had no intellectual successors… This is true even of scholars working in Kluckhohn’s own intellectual tradition. Some of the most influential American cultural theorists of the ‘60s and ‘70s—I am thinking here especially of Clifford Geertz and David Schneider—were in many ways continuing in it, but they moved in very different directions.

THE LIMITATIONS ON ECONOMIC ANTHROPOLOGY

Practically from the beginnings of modern anthropology, there have been efforts to apply the tools of microeconomics to the study of non-Western societies.

He explains that this is because economics “has long had the additional advantage of being seen as the very model of “hard” science by the sort of people who distribute grants.”

It also has the advantage of joining an extremely simple model of human nature with extremely complicated mathematical formulae that non-specialists can rarely understand, much less criticize.

THE MINI/MAX APPROACH OF ECONOMICS

Its premises are straightforward enough. Society is made up of individuals. Any individual is assumed to have a fairly clear idea what he or she wants out of life, and to be trying to get as much of it as possible for the least amount of sacrifice and effort. (This is called the “mini/max” approach. People want to minimize their output and maximize their yields.) What we call “society”—at least, if one controls for a little cultural “interference”—is simply the outcome of all this self-interested activity.

Bronislaw Malinowski was already complaining about this sort of thing in 1922, in what is arguably the first book-length work of economic anthropology: Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Such a theory would do nothing, he said, to explain economic behavior in the Trobriand Islands:

“Another notion which must be exploded, once and for ever, is that of the Primitive Economic Man of some current economic textbooks... prompted in all his actions by a rationalistic conception of self-interest, and achieving his aims directly and with the minimum of effort. Even one well established instance should show how preposterous is this assumption. The primitive Trobriander furnishes us with such an instance, contradicting this fallacious theory. In the first place, as we have seen, work is not carried out on the principle of the least effort. On the contrary, much time and energy is spent on wholly unnecessary effort, that is, from a utilitarian point of view.”

Such examples could be multiplied endlessly, and, in the early days of anthropology, they were. It didn’t make much difference. Every decade or so has seen at least one new attempt to put the maximizing individual back into anthropological theory, even if economic theory itself usually ends up having to bend itself into ribbons in order to do so.

In fact, the effort to reconcile the two disciplines is in many ways inherently contradictory. This is because economics and anthropology were created with almost entirely opposite purposes in mind.

Economics is all about prediction. It came into existence and continues to be maintained with all sorts of lavish funding, because people with money want to know what other people with money are likely to do. As a result, it is also a discipline that, more than any other, tends to participate in the world it describes…

Economics, as a discipline, has almost always played a role in defining the situations it describes.

Nor do economists have a problem with this; they seem to feel it is quite as it should be.

Here, we must read between the lines. Graeber seems to be saying “listen, guys, economics is not a fucking science, let alone a “hard science”. Anthropology has a much better claim to be a science than economics does.

If you think about it, he’s absolutely right. Economics is the furthest thing from a science. To call economics a science is to suggest that economists are capable of neutrality, which is have no economic interests and no economic agenda, which is literally NEVER true.

Think about it: Science is about observation. It requires objectivity, which is to say a certain neutrality. Science is about testing hypotheses through repeatable experiments. It requires a certain disinterested aloofness - one must be willing to be proven wrong. Indeed, science advances through an elaborate process of attempting to disprove its own assumptions. That is what conflicts of interest corrupt science. If one is simply trying to prove what one already believes, the scientific method becomes nothing more than a ritualized way of confirming one’s biases.

This is contrary to the spirit of science, and is basically just a big waste of everyone’s time. It’s just lying with extra steps.

ANTHROPOLOGY IS COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FROM ECONOMICS

Anthropology was from the beginning entirely different. It has always been most interested in the action of those people who are least influenced by the practical or theoretical world in which the analyst moves and operates. Anthropologists are most interested in the people whose understanding of the world, and whose interests and ambitions, are most different than their own. As a result, it is generally carried out completely without a thought to furthering those interests and ambitions.

Economics, then, is about predicting individual behavior; anthropology, about understanding collective differences.

As a result, efforts to bring maximizing models into anthropology always end up stumbling into the same sort of incredibly complicated dead ends. The classic case studies of economic anthropology, for instance—Franz Boas’ reports on the Kwakiutl potlatch (1897, etc.) or Malinowski’s on Trobriand kula exchange (1922)—concerned systems of exchange that seemed to work on principles utterly different from the observers’ own: ones in which the most important figures seemed to be not so much trying to accumulate wealth as vying to see who could give the most away.

In 1925, Marcel Mauss coined the phrase “gift economies” to describe them.

Actually, the existence of gifts—even in Western societies—has always been something of a problem for economists. Trying to account for them always leads to some variation of the same, rather silly, circular arguments.

Q: If people only act to maximize their gains in some way or another, then how do you explain people who give things away for nothing?

A: They are trying to maximize their social standing, or the honor, or prestige that accrues to them by doing so.

Q: Then what about people who give anonymous gifts?

A: Well, they’re trying to maximize the sense of self-worth, or the good feeling they get from doing it.

This type of argument is likely to be made by followers of Ayn Rand, Milton Friedman, and Anton Lavey, the founder of the Church of Satan. Most recently, it has reared its ugly head under the name of “effective altruism”.

If you are sufficiently determined, you can always identify something that people are trying to maximize. But if all maximizing models are really arguing is that “people will always seek to maximize something,” then they obviously can’t predict anything, which means employing them can hardly be said to make anthropology more scientific. All they really add to analysis is a set of assumptions about human nature. The assumption, most of all, that no one ever does anything primarily out of concern for others; that whatever one does, one is only trying to get something out of it for oneself. In common English, there is a word for this attitude. It’s called “cynicism.” Most of us try to avoid people who take it too much to heart. In economics, apparently, they call it “science.”

Zing!

Still, all these dead ends did produce one interesting side effect. In order to carry out such an economic analysis, one almost always ends up having to map out a series of “values” of something like the traditional sociological sense—power, prestige, moral purity, etc.,—and to define them as being on some level fundamentally similar to economic ones. This means that economic anthropologists do have to talk about values. But it also means they have to talk about them in a rather peculiar way.

When one says that a person is choosing between having more money, more possessions, or more prestige, what one is really doing is taking an abstraction (“prestige”) and reifying it, treating it as an object not fundamentally different in kind from jars of spaghetti sauce or ingots of pig iron. This is a peculiar operation, because in fact prestige is not an object that one can dispose of as one will, or even, really, consume; it is rather an attitude that exists in the minds of other people. It can exist only within a web of social relations.

This is incredibly profound.

PROPERTY IS TABOO

He then goes on to touch on some very interesting thoughts on the nature of property.

Of course, one might argue that property is a social relation as well, reified in exactly the same way: when one buys a car one is not really purchasing the right to use it so much as the right to prevent others from using it—or, to be even more precise, one is purchasing their recognition that one has a right to do so. But since it is so diffuse a social relation—a contract, in effect, between the owner and everyone else in the entire world—it is easy to think of it as a thing. In other words, the way economists talk about “goods and services” already involves reducing what are really social relations to objects; an economistic approach to values extends the same process even further, to just about everything.

This is a very interesting definition of property, one that I have not seen before. He is defining property as “the exclusive right to legitimately use an object within an existing society”.

This is what I call the “Don’t Touch My Bike” principle. In anthropological terms, this is very literally a taboo. The term taboo, which comes from Polynesia, is often defined as “not to be touched”.

In reality, the only thing spaghetti sauce and prestige have in common is the fact that some people want them. What economic theory ultimately tries to do is to explain all human behavior—all human behavior it considers worth explaining, anyway—on the basis of a certain notion of desire, which then in turn is premised on a certain notion of pleasure. People try to obtain things because those things will make them happy or gratify them in some way (or at least because they think they will).

In the end, most economic theory relies on trying to make anything that smacks of “society” disappear. But even if one does manage to reduce every social relation to thing, so that one is left with the empiricist’s dream, a word consisting of nothing but individuals and objects, one is still left to puzzle over why individuals feel some objects will afford them more pleasure than others. There is only so far one can go by appealing to physiological needs.

THE MARKET HAS NEVER BEEN FREE

Graeber then enters introduces the work of a Hungarian economist Karl Polanyi.

Polanyi’s most famous work, The Great Transformation, was an account of the historical origins, in eighteenth and nineteenth century England, of what we now refer to as “the market.” In this century, the market has come to be seen as practically a natural phenomenon—a direct emanation of what Adam Smith once called “man’s natural propensity to truck, barter and exchange one thing for another.”

Actually, this attitude follows logically from the same (cynical) theory of human nature that lies behind economic theory. The basic reasoning— rarely explicitly stated—runs something like this. Human beings are driven by desires; these desires are unlimited. Human beings are also rational, insofar as they will always tend to calculate the most efficient way of getting what they want. Hence, if they are left to their own devices, something like a “free market” will inevitably develop.

Of course, for 99% of human history, none ever did, but that’s just because of the interference of one or another state or feudal elite. Feudal relations, which are based on force, are basically inimical to market relations, which are based on freedom; therefore, once feudalism began to dissolve, the market inevitably emerged to take its place.

The beauty of Polanyi’s book is that it demonstrates just how completely wrong that common wisdom is. In fact, the state and its coercive powers had everything to do with the creation of what we now know as “the market”—based as it is on institutions such as private property, national currencies, legal contracts, credit markets. All had to be created and maintained by government policy.

The market was a creation of government and has always remained so. If one really reflects on the assumptions economists make about human behavior, it only makes sense that it should be so: the principle of maximization after all assumes that people will normally try to extract as much as possible from whoever they are dealing with, taking no consideration whatever of that other person’s interests—but at the same time that they will never under any circumstances resort to any of the most obvious ways of extracting wealth from those towards whose fate one is indifferent, such as taking it by force. “Market behavior” would be impossible without police.

Polanyi goes on to describe how, almost as soon as these institutions were created, men like Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo appeared, all drawing analogies from nature to argue that these new forms of behavior followed inevitable, universal laws… But in most societies, such institutions did not exist; one simply cannot talk about an “economy” at all, in the sense of an autonomous sphere of behavior that operates according to its own internal logic.

THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS “THE ECONOMY”

This point is worth dwelling upon for a moment.

This may surprise you, but economics did not exist before 1776, when Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations.

Wikipedia explains:

The Wealth of Nations is the first modern work that treats economics as a comprehensive system and as an academic discipline. Smith refuses to explain the distribution of wealth and power in terms of God's will and instead appeals to natural, political, social, economic, legal, environmental and technological factors and the interactions among them.

Prior to the invention of economics, the concept of economics simply didn’t exist as a concept.

What economics did was create an imaginary sphere of human activity where “economic activity” was separated from other aspects of society, notably religion and culture. This is what Graeber means when he defines “the economy” as “an autonomous sphere of behavior that operates according to its own internal logic.”

In reality, there is no such thing as the economy. It is simply a linguistic trick invented by statists to make state power seem legitimate. What economists call “the economy” is simply a name for the “process through which the society provides itself with food, shelter, and other material good. This process is entirely embedded in society and not a sphere of activity that can be distinguished from, say, politics, kinship, or religion.”

Graeber then clarifies that economists are by no means wrong about everything, and that we should understand that:

[E]conomic institutions can be seen as a means of social integration—one of the ways society creates a network of moral ties between what would otherwise be a chaotic mass of individuals—or, if not that, then at least the means by which “society” allocates resources.

He concludes:

The obvious question is how “society” motivates people to do this. Without some theory of motivation, one is left with a picture of automatons mindlessly following whatever rules society lays down for them, which at the very least makes it difficult to understand how society could ever change.

Graeber’s argument is extremely solid. If we define politics as “everything having to do with decision-making in groups” and economics as “everything having to do with the allocation of resource in groups”, that we must conclude that economics is one of the most important aspects of politics.

The important thing to understand is that 1) economics is a branch of politics, not the other way around, and 2) how resources are allocated has everything to do with the relative bargaining power of different members of society, which is say power.

LINGUISTIC VALUE

Okay, this is where we get to the advanced stuff, so I’m going to need you to play close attention here. You might want to go make yourself a couple of coffee.

As you’ll recall, Graeber identifies three large streams of thought that converge in the term “value”. They are:

“values” in the sociological sense: conceptions of what is ultimately good, proper, or desirable in human life

“value” in the economic sense: the degree to which objects are desired, particularly, as measured by how much others are willing to give up to get them

“value” in the linguistic sense, which goes back to the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure (1966), and might be most simply glossed as “meaningful difference”

I think the first two meanings are self-explanatory, but unless you’ve studied linguistics, the third will require some explanation.

Linguists have long been in the habit of speaking of the meaning of a word as its “value.”

Got that? The value of a word is the meaning of that word. Simple enough, right? Well hang onto this easily graspable concept, because things are about to get REAL trippy.

THE LINGUISTIC VALUE OF A WORD IS WHAT THAT WORD MEANS

From quite early in the history of anthropology, there have been efforts connect this usage to other sorts of value.

One of the most interesting can be found in Evans-Pritchard’s The Nuer, a discussion of the “value” of the word cieng, or “home.” For a Nuer, Evans-Pritchard notes, the “value” of this word varies with context; a speaker can use it to refer to one’s house, one’s village, one’s territory, even Nuerland as a whole.

But it is more than a word; the notion of “home,” on any of these levels, also carries a certain emotional load. It implies a sense of loyalty, and that can translate into political action. Home is the place one defends against outsiders. So we are talking about value in the sociological, “values” sense as well.

“Values,” Evans-Pritchard says, “are embodied in words through which they influence behavior”. Or, alternatively, the notion of “home,” when it serves to determine who one considers a friend, and who an enemy, in the case of potential blood-feuds, “becomes a political value” as well.

Note here how “value” slips back and from “meaning” to something more like “importance”: one’s home is essential to one’s sense of oneself, one’s allegiances, what one cares about most in life.

This was a fascinating start, but it never really went anywhere. When a contemporary anthropologist speaks of the value of words, instead, they are almost invariably referring back to the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure, founder of modern, structural linguistics.

In his Course of General Linguistics, Saussure argued that one could indeed speak of any word as having a value, but that this value was essentially “negative.”

By this he meant that words take on meaning only by contrast with other words in the same language. Take for example the word “red.” One cannot define its meaning, or “value,” in any given language, without knowing all the other color terms in the same language; that is, without knowing all the colors that it is not.

We might translate a word in some African language as “red,” but its meaning (or value) would not be the same as the English “red” if, say, that other language does not have a word for “brown.”

People in that language might then be in the habit of referring to trees as red. The most precise definition of the English “red,” then, would be: the color that is not blue, not yellow, not brown, etc.

It follows then that in order to understand the “value” of any one color term one must also know those of all the others in that language: the meaning of a term is its place in the total system.

This is a tricky idea to wrap your mind around, so I encourage to pause for a moment and watch this video, which explains how different languages divide up the colour spectrum in different ways.

It’s a good use of ten minutes, I promise.

In other words, the meaning of words only makes sense within a system of meaning, but the meaning of things is shaped by the language we speak.

Saussure ultimately believed that “linguistics should be considered just one sub-field of a master discipline that he dubbed semiology, the science of meaning.”

Saussure’s arguments of course had an enormous impact on anthropology, and were the most important influence on the rise of Structuralism—which took off from Saussure’s suggestion that all systems of meaning are organized on the same principles as a language, so that technically, linguistics should be considered just one sub-field of an (as yet non-existent) master discipline that he dubbed semiology, the science of meaning.

Saussure’s approach was more about vocabulary than grammar, more about nouns and adjectives than verbs. It was concerned with the objects of human action more than with the actions themselves. Not surprising, then, that those who tried to follow Saussure’s lead and actually create this non-existent science tended to be most successful when exploring the meaning of physical objects. Objects are defined by the meaningful distinctions one can make between them. To understand the meaning (value) of an object, then, one must understand its place in a larger system.

In other words:

Nothing can be analyzed in isolation. In order to understand any one object, one must first identify some kind of total system. This became the trademark of Structuralism: the point of analysis was always to discover the hidden code, or symbolic system, which tied everything together.

Almost inevitably, though, the question became how to connect this sort of value to value in either of the other two senses.

To understand why people want to buy things we have to understand the place that thing has in a larger code of meaning.

The word “value” may refer to the price of something or the meaning of something, or in general to that which people hold “dear,” either morally or monetarily. So, value in each sense is ultimately the same. Things are meaningful because they are important. Things are important because they are meaningful.

You with me? How fucking trippy is that? Everything comes down to language.

Graeber then takes a very long time to say something that is obvious to anyone who has ever worked in sales: people determine the value of items by means of comparison.

The colour red, for instance, defined by what it is not. It is that segment of the visible light spectrum which is not blue and not green.

When asking a question such as “What is Money?”, this may prove helpful. If we understand that money is debt, and we ask ourselves what the opposite of debt is, we may conclude that money is the opposite of free exchange. We might even conclude that money is the ordering principle of an unfree society, which would explain why money didn’t exist before states.

He continues:

Similarly, Structuralist approaches in anthropology—as exemplified in the works of Claude Levi-Strauss—tend to focus on how members of different cultures understand the nature of the universe, and for this they can be remarkably revealing; but the moment one tries to understand how, say, one thing is seen as better—preferable, more desirable, more valuable—than another, problems immediately emerge.

People do not buy things simply because they recognize them as being different than other things in some way. Even if they did, this would do nothing to explain why they are willing to spend more on certain things than others.

In other words, there is literally no way to objectively measure human desire. Saussure’s “science of meaning” is impossible, because science

There is a Spanish saying that goes “De los gustos no hay nada escrito”.

In other words, there’s no accounting for taste.

Some people like Mozart, and some people like grindcore.

Some like fine art, others prefer scat porn.

Fashion plays a part, but at the end of the day, you like what you like.

THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS POLITICAL CORRECT ANTHROPOLOGY

One thing that Graeber does not mention that Claude Levi-Strauss, the greatest of the Structuralists, ultimately decided that all human cultures were elaborate mechanisms for “the exchange of women”.

The only author who has made a consistent effort to develop a theory of value along Structuralist lines is Louis Dumont.

Dumont is of course best known for having been almost single-handedly responsible for popularizing the concept of “hierarchy” in the social sciences. His notion of value, in fact, emerges directly out of his concept of hierarchy.

Classical Structuralism, according to Dumont, was developed as a technique meant to analyze the formal organization of ideas, not values. Carrying out a structural analysis means, first, identifying certain key conceptual oppositions—raw/cooked, pure/impure, masculine/feminine, consanguinity/affinity, etc.—and then mapping out how these relate to one another, say, within in a series of myths or rituals, or perhaps an entire social system. What most Structuralists fail to realize, Dumont adds, is that these ideas are also “values.” This is because with any such pair of terms, one will be considered superior. This superior term always “encompasses” the inferior one.

The notion of encompassment is in turn the key to Dumont’s notion of hierarchy. One of his favorite illustrations is the opposition of right and left. Anthropologists having long noted a tendency, which apparently occurs in the vast majority of the world’s cultures, for the right hand to be treated as somehow morally superior to the left. In offering a handshake, Dumont notes, one must normally extend one hand or the other. The right hand put forward thus, in effect, represents one’s person as a whole—including the left hand that is not extended.

Hence, at least in that context, the right hand “encompasses” or “includes” the left, which is also its opposite. (This is what he calls “encompassing the contrary.”) This principle of hierarchy, he argues, applies to all significant binary oppositions—in fact Dumont rejects the idea that two such terms could ever be considered equal, or that there might be any other principle of ranking, which as one might suspect has created a certain amount of controversy, since it pretty obviously isn’t true.

So: meaning arises from making conceptual distinctions. Conceptual distinctions always contain an element of value, since they are ranked.

Even more important, the social contexts in which these distinctions are put into practice are also ranked. Societies are divided into a series of domains or levels, and higher ones encompass lower ones—they are more universal and thus have more value. In any society, for instance, domestic affairs, which relate to the interests of a small group of people, will be considered subordinate to political affairs, which represent the concerns of a larger, more inclusive community; and likely as not that political sphere will itself be considered subordinate to the religious or cosmological one, where priests or their equivalents represent the concerns of humanity as a whole before the powers that control the universe.

Perhaps the most innovative aspect of Dumont’s theory is the way that the relations between different conceptual terms can be inverted on different levels. Since Dumont developed his model in an analysis of the Indian caste system, this might make a good illustration.

On the religious level, where Brahmans represent humanity as a whole before the gods, the operative principle is purity. All castes are ranked according to their purity, and by this standard Brahmans outrank even kings. In the subordinate, political sphere in which humans relate only to other humans, power is the dominant value, and in that context, kings are superior to Brahmans, who must do as they say. Nonetheless Brahmans are ultimately superior, because the sphere in which they are superior is the most encompassing.

None of this, of course, applies to contemporary Western society, but according to Dumont, the last three hundred years or so of European history have been something of an aberration. Other societies (“one is almost tempted to say, ‘normal ones’”) are “holistic,” holistic societies are always hierarchical, ranked in a series of more and more inclusive domains. Our society is the great exception because for us, the supreme value is the individual: each person being assumed to have a unique individuality, which goes back to the notion of an immortal soul, which are by definition incomparable. Each individual is a value unto themselves, and none can be treated as intrinsically superior to any other. In most of his more recent work in fact Dumont has been effectively expanding on Polanyi’s arguments in The Great Transformation, arguing that it was precisely this principle of individualism that made possible the emergence of “the economy.”

In the footnotes, we get a hint that Graeber is talking about gender relations:

[I]n the secular sphere, it is women who give birth to men (a clear gesture of encompassment), on the higher level of cosmic origins, it was the other way around, with Eve produced from Adam’s rib.

Throughout Graeber’s work, you will encounter things that make you wonder what his true feelings regarding gender relations are.

He is clearly sympathetic to Structuralist perspectives, yet he doesn’t mention the conclusion that Structuralism ultimately reached. Could this have been out of deference to the social mores of the early 21st century, when questioning the fundamental assumptions of feminists was unthinkable?

ARE WOMEN SLAVES?

Hey Folks, As you’re probably aware, I’ve been exploring a very deep rabbit hole lately - the question of how civilization spread across the entire world, and how we can recast the story of humanity so as to create a social reality that is better optimized to human needs and desires.

Why does Graeber ignore the fact that cultures are intergenerational survival strategies?

If we understand every human culture as a way of adapting to material conditions, one conclusion is inescapable: human cultures evolve over time as strategies for survival. In other words, they are about reproduction.

If we’re going to talk about culture in any kind of meaningful, big-picture way, we’re going to have acknowledge that successful reproduction depends on three things:

Fertility

Mating

Child-rearing

VALUE IS TO DESIRE AS SUPPLY IS TO DEMAND

Throughout Toward An Anthropological Theory of Value, Graeber ignores that in every culture, two of the most desired and most valuable things are 1) a desirable mate, and 2) children.

I agree with Graeber that value is to desire as supply is to demand. So why does he ignore universal desires?

What do human beings ultimately want?

Well, when they’re children, they want to play and have fun. When they’re old enough, they want to play and have fun sexually. Eventually, they want to have children. Once they have children, they want to provide the best possible environment for their children. Once their children are grown, they want prestige - in other words, they want to be respected by the younger members of their society.

I hold these desires to be universal. I would expect to find them in every culture that has ever existed since the beginning of time. If we are looking for human universals, we should start here.

These desires are by no means a comprehensive list, by the way. Different cultures will encode different values, which is turn will lead to different tastes, which also change over time. I would also expect to find fashion in every culture ever, and one of the features of fashion is that it changes over time.

Fashion, the desire to be approved of by one’s peers, is absent from Graeber’s analysis, but it is known aspect of human psychology. Sociologists have a nifty term for it: the “social desirability bias”.

This is complicated by the fact that people lie about their desires all the time, which is where the concepts of “Emic” and “Etic” come in.

Here, watch this video:

One of the things that people most commonly lie about is sexual desire.

If a woman would absolutely love to fuck her best friend’s husband’s brains out, you can bet that she’ll never admit it.

This is what makes talking about desire so tricky. We are all expected to pretend not to have desires that are socially unacceptable.

But the question is politically important, because what do think starts wars?

I’ve got three words for you: Helen of Troy.

Men fight over women more often than anything else, and women are, if anything, even worse.

WIVES AND HUSBANDS ARE TABOO

Let’s revisit the definition of the word taboo. If you’ll recall, it means “not to be touched”.

According to Graeber, property is “the exclusive right to legitimately use a thing”.

So what do you think marriage is?

If you have a husband, you own his penis. If you have a wife, you own her vagina.

This is true even if you’re in an open marriage. In open marriages, the legitimate right of a wife to fuck someone else is conferred by the consent of her husband, and vice-versa.

Can you not see that property rights arise from customs of sexual exclusivity? How do you think those started?

According to Terence McKenna, the origin of the state is the recognition of male paternity.

This may surprise some of you, but there are descriptions in the anthropological record of cultures in which people had no idea that babies had fathers. They must have known that women could not have children before their first menstruation, but it apparently never occurred to them that babies were the result of any specific act of copulation… After all, before the invention of pregnancy tests, it would have probably taken two or three months before a women even knew she was pregnant.

Graeber briefly acknowledges this is a later chapter, saying in passing that:

Trobriand opinions on the subject of procreation have been the subject of endless debate, ever since Malinowski announced that the Trobrianders he knew claimed that sexual intercourse was not the cause of pregnancy.

According to Malinowski:

While women could not become pregnant if they had never had sex at all, as soon as the womb had so been “opened,” pregnancy occurred when certain ancestral spirits called baloma entered a woman while she was bathing, whether or not the woman in question had recently had sex. Descent was strictly through the mother’s line; the men had nothing to do with it.

AN ANARCHIST THEORY OF EVOLUTION

And the heart grieves in its madness, tracing that sore. Bitterness blooms its own rare fruit Out of the spiked earth, scars of alienation Lost is the primeval oneness What unity prevails? Desire. That the bomb should drop, great cities go down, all the heckling nations rub each other out.

WAS THE FALL FROM GRACE CAUSED BY THE RECOGNITION OF MALE PATERNITY?

According to Terence McKenna, the Terror of History became when human beings figured out that babies had fathers.

At that point, they began to attempt to jealously guard access to female fertility, so as to be ensured that they could be assured that their partner’s children were biologically theirs.

This must surely have been resisted by females, who are no less naturally horny than men are.

One can easily imagine what would have happened next. The most dominant men would then claim the most sexually attractive females for themselves.

This is my theory about what caused the Fall from Grace.

The story of Man’s exile from the Garden of Eden is clearly told from a male perspective. Eve is blamed for giving into temptation, and for sharing the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge with Adam.

What was this knowledge that was responsible for destroying the earthly paradise? We aren’t told.

Could it have been the recognition of male paternity? Have men been warring for five millennia because they want to control access to female fertility?

The idea makes a lot of sense to mind. From “my woman”, it is a short distance to “my berry patch”, “my fishing spot”, “my village”, eventually leading to “my army” and “my country”. All are claims over the exclusive right to legitimate use of something.

Because some women are more attractive then others, this would lead to competition amongst males for the most desirable mates. This likely led to the first gangs, which were probably agreements amongst males not to fuck each other each other’s wives.

Jordan Peterson calls this institution, which has been a mainstay of patriarchal religions for thousands of years, “enforced monogamy”.

“THOU SHALT NOT FUCK ANYONE BUT ME” was most likely the first commandment, which is to say law.

The first anarchist was the first woman to say “NO! IT’S MY BODY, AND MY CHOICE. YOU DON’T GET TO TELL ME WHAT TO DO!”

And the world has been at war ever since.

THE ORIGINS OF WAR

So, to recap, I believe the origins of war can be traced back to four interrelated factors:

The invention of the institution of “enforced monogamy” (i.e. patriarchy)

Female resistance to male dominance (primal feminism)

Competition amongst men for the most sexually desirable mates (capitalism)

Male and female resistance to male domination (anarchism)

The second anarchist, by the way, was the first person to stick up for a woman’s right to choose who to fuck. I’m guessing that was a man who wanted to keep fucking his lover, but who knows? Maybe it was her mommy and daddy, or her brothers.

Over time, this would have led to schisms, creating rival gangs. May rival gangs probably hated each other because they originally one gang which split into two, likely because someone felt that their property claim over a woman’s vagina had been violated.

Given that these gangs would have also engaging in hunting and/or fishing, they would be well-positioned to begin waging war.

After all, the main difference between a hunting party and a war party is that in the latter case, you (usually) don’t eat your prey.

Along the way, female psychology evolved to adapt to these new conditions. Women realized that winning the game of life was a matter of procuring the most desirable mate. At this point, they began seeing other women as competition, because there were, of course, a limited number of desirable mates. Female solidarity has never recovered, because woman who succeed in securing a desirable mate is now in his coalition. In effect, she has joined his gang. In the end, women became just as territorial as men.

Presumably, females have always valued men as providers and protectors, and this is important to keep in mind. The female desire for male protection is likely derived from an earlier phase of our evolution, when humans were prey animals for predators such as sabre-toothed cats.

If you’re a woman and you’re resentful of male aggression, just keep it mind it’s the reason that humans survived the Stone Age. You shouldn’t be ashamed for wanting male protection, and you have always needed it. If it makes you feel any better, we need you just as much as you need us. You literally made us and every one of us. None of us was hatched from a pod. None of us fell from the sky.

Somehow, feminists started thinking that viewing women as “little more than baby-making factories”, as if it was offensive to think that the most important thing that women do is produce the next generation. Apparently it would be more liberating to work in an actual factory making bombs or something.

From a big picture perspective, the most important thing that human beings produce are human beings. Human cultures are collective intergenerational survival strategies. If you don’t want to have kids, don’t have kids, but raising children is the most important thing that women do. The same is true of men. The survival of the human race depends upon successful reproduction. That’s just a fact.

Wage slavery was sold to you as liberation, and you fell for it hook, line, and sinker. If it makes you feel any better, so did we.

If you’re wondering how this happened, by the way, I would encourage you watch the excellent BBC series Century of Self, which explains how the advertising industry helped create modern feminism in order to produce more consumers.

As Mary Harrington has noted, there is nothing inherently liberating about work. Some women are lucky to earn a living doing something they are passionate enough, but if you’re like most people, you go to work because you need the money.

Has feminism made life better women because they now have equal access to be wage slaves? How you feel about this issue probably has a lot to do with or not you’re a mother. If you’re childless, you might want to get out of the house for the sake of getting out of the house, but I would suspect that most mothers would prefer to stay home.

Feminism has failed.

Graeber sums things up by saying:

By the early ‘80s, there was a general consensus that this was the great problem of the day: how to come up with a “dynamic” theory of structuralism, one that could account for the vagaries of human action, creativity, and change.

If it were someone else, I would assume that this sentence has just meaningless mumbo-jumbo written by an academic trying to sound smart. But this is David Graeber we’re talking about here. He didn’t talk out of his ass.

I could be misconstruing things, but I think this is code for “anthropology and woke feminism are incompatible”.

Anthropology didn’t really resolve these dilemmas. For the most part, it just skipped over them. The discipline moved on to other issues: concerning the politics of ethnographic fieldwork, memory, the body, transnationalism, and so forth. Structuralism faded out of prominence, then gradually came to seem ridiculous; theories that concentrated on power (Foucault) largely replaced it; there was (and is) a general feeling that the debate was over.

As we will see in the next chapter, though, most of the new theories that seem to have made the old arguments irrelevant are, at least in many of their aspects, little more than retooled versions of the same old thing. Nor do I think that ignoring the problem is necessarily the best way to make it go away.

Now, obviously, I’m nowhere near as familiar as David Graeber with the anthropological record, but I’m honestly confused - what exactly is the problem? Men trading women? What are about the Haudenosaunee?

In a later chapter, Graeber notes:

Longhouses were governed by councils made up entirely of women, who, since they controlled its food supplies, could evict any in-married male at will. Villages were governed by both male and female councils. Councils on the national and league level were also made up of both male and female office-holders. It’s true that the higher one went in the structure, the less relative importance the female councils had—on the longhouse level, there wasn’t any male organization at all, while on the league level, the female council merely had veto power over male decisions—but it’s also true that decisions on the lower level were of much more immediate relevance to daily life.

What? The only power that women had was to prevent any male decisions they didn’t agree with? You mean total power? Is that not fucking enough for feminists?

If I understand correctly, it was usually women who arranged marriages in Haudenosaunee society.

Graeber acknowledges:

In terms of everyday affairs, Iroquois society often seems to have been about as close as there is to a documented case of a matriarchy.

I personally have yet to be convinced that human culture boils down to men trading women, but I certainly do agree that in the traditional cultures I’m most familiar with, such as the Wet’suwet’en, Haudenosaunee, and Mi’kmaq, women were exchanged between different clans. But so are men!

That’s what the clan system is all about. The key to maintaining harmonious relationships with one’s neighbours is to treat them as family, and the easiest way to do that is to encourage exogamy. It also keeps genes moving around, which leads to better human specimens.

If the clan system is what Levi-Strauss is referring when he speaks of “groups of men trading women”, I definitely don’t see what the problem is.

I’m genuinely confused, but I guess that makes sense. Graeber isn’t saying that Levi-Strauss was right, only that there are unresolved dilemmas which have been holding anthropological theory back.

TO BE CONTINUED!!!

ARE WOMEN SLAVES?

Hey Folks, As you’re probably aware, I’ve been exploring a very deep rabbit hole lately - the question of how civilization spread across the entire world, and how we can recast the story of humanity so as to create a social reality that is better optimized to human needs and desires.

I would translate "De los gustos no hay nada escrito" as something like "As tastes go, there is nothing written in stone." Here, I perceive "escrito" as meaning decreed, set down.

You’ve taught me so much. For ex, I did not know about Graeber’s work before you.