Hey Folks,

David Graeber died four years ago today, and we still don’t know how he died.

I’ve been quite vocal that I think that the circumstances of his death were mysterious, but I don’t want to get into the weeds of that right now. I’d rather focus on how we might best honour his memory by keeping his ideas alive, which I think is what he would have wanted.

David Graeber is, in my opinion, one of the most important thinkers of the 21st century thus far. I also think that he was one of the greatest anthropologists of all time. Yet no biography of his epic life has yet appeared. What gives? How could such a thinker be so easily forgotten?

Okay, okay, that’s an exaggeration. David Graeber hasn’t been forgotten. And there has been one book of essays about his ideas which has appeared since his death, so that’s definitely something. That book is called As If Already Free, and I have written about it here.

To me, this isn’t nearly enough. David Graeber’s magnum opus Debt: The First Five Thousand Years is the anarchist answer to Das Kapital and The Wealth of Nations. It is the best book on economics that I have ever read. Before it was written, there was no such work.

Today, on the 4th anniversary of his death, I am re-committing to doing my part to honour his legacy by writing about his ideas and building upon them, because it is clear to me that the core of his message is not generally understood even by most people who interest themselves in anarchist philosophy.

I suppose that part of the problem is that, due to the grandeur of his ideas, his message for the world is unsummarizable. He left behind over 5000 pages of published writing when he died. I have read probably a bit more than half of it, and I don’t think he ever really wasted words. He just had a lot to say. I don’t think there will a single volume which will do justice to his ideas. I am convinced that his oeuvre is among the most brilliant in the anarchist canon. No one who takes a serious interest in anarchist theory should neglect it.

But David Graeber was not just a brilliant thinker, he was also a flesh-and-blood human being who walked among us. Today, I would like to honour that man by posting a touching eulogy written by Erica Lagalisse, his partner of seven years.

Stay tuned for more about the great David Graeber in the days and weeks to come!

for the Wild,

crow Qu’appelle

P.S. Here are some some videos and articles that will get you started on exploring Graeber’s ideas if you aren’t already familiar with them.

Pro tip: Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology is the place to start:

The Elvis of Anthropology

Eulogy for David Graeber

Erica Lagalisse, October 1st 2020

The feeding frenzy has begun. Everyone was best friends with David Graeber. David would have liked it – he had come to rely on superficial forms of recognition. He would also be mad (so mad) to see all the politicos who never gave him the time of day now honouring him in public. Yes, I can just see him – sitting in the bath, with his laptop perched on the side of the tub, he gesticulates wildly at Twitter. His coffee cup is leaving brown rings on the porcelain. It’s all so endearing now.

I want to honour David by sharing what I know of his wishes. From 2005 when I first wrote to him grateful for Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (2004), David and I carried on the most challenging and fun intellectual dialogue I have ever known, first by email, later in person, finally living together – we were in a relationship for seven years, engaged throughout 2013-2017. In the beginning we poured over an early manuscript of An Ethnography of Direct Action (2009), which unfolds partly in my home town Montréal, while his little-known MA thesis soon became a key reference in my own dissertation on anarchist social movements – an antidote to his own. He read very few of the feminist texts I recommended, but often cited them where I told him to. I remember he wrote Debt: The First Five Thousand Years (2011) before the Pirates book (as yet unwritten) because the economy crashed. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if he hadn’t. Maybe he wouldn’t have become famous, and we could have had a life, and he would still be here today. I saw what unfolded. I saw him shake his fists and mouth curses every time an interviewer for Debt brought up Occupy. I saw his initial attempts to avoid being dubbed ‘leader’ of that movement, while still very much wanting recognition for his scholarly work in anthropology, his life-long pride and joy.

David was both brilliant and problematic. He was someone who learned early on to avoid physical and emotional discomfort by dissociating into mental play. His childhood was painful and characterized by rejection – he probably cultivated imaginative distractions to get by. Perhaps he was already difficult as a child. Perhaps as a working-class boomer (vs. middle class millennial) no allowances were to be made for him being “on the spectrum”. In any case David could not feel his body. If he tried to place his attention even briefly in his chest, on his breathing, he felt he would suffocate and die. He could never remember it being otherwise. I think being inside his body just hurt too much, emotionally and physically. Thinking had been better than feeling for a long time.

Later on I will need to vent about how it was largely his (growing) social privileges that enabled him to get through life without realizing his dissociation or hitting bottom – a woman like David is not considered a “mad professor” or “package deal” but a “flaky psychobitch”, and a person of colour with his temperament might easily be murdered by police. Part of my heart still goes out to him when I remember us, alone together, riddled with our respective traumas, fervently discussing every major Western philosophical text on Desire – Hegel, Schopenhauer, Kojeve, Butler, Lacan, Deleuze, De Beauvoir, Kristeva – because that was the closest we could get to intimacy. So many word games, inside jokes and giggles papered over our deep loneliness. There once was a German named Hegel, whose Logic was shaped like a bagel, he was very clever, but his wife said whatever, I’d rather be hanging with Schlegel. On more active days we would write jokes about classical Greek figures in the genre of Nasruddin tales.

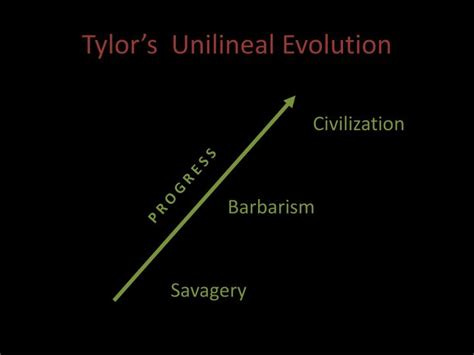

David was a magnificent nerd. He was also a great researcher and rigorous scholar and deserves to be remembered as he most wished – for his contributions to anthropology. Not only for popularizing the discipline, and inspiring students with his enthusiasm and approachability, but because his research intervened in long-standing classical disciplinary debates on value, sacrifice, kingship, hierarchy and social change, in what he did tend to glorify as the ‘grand tradition’. That tradition is indeed colonial and masculine. I was the first to complain (literally) about that book he wrote with Marshall Sahlins On Kings (2017) that somehow avoids addressing how Kings are not Queens. Yet there remains certain value in the anthropological archive, however begotten by violence and trauma, just as there is value in David’s expansive, lop-sided intelligence, however begotten by violence and trauma – and constitutive of it. Both things are true. David was one of few living anthropologists well-versed and politically-motivated enough to show us how classical anthropological methods can continue to teach us about humanity and our collective possibilities for social change. As I explain in my upcoming essay Anthropology (2021), I find David’s cross-cultural study of property, hierarchy and ‘avoidance’ – one of his traditional endeavours, and early replies to Dumont (1970) – useful to think with in my own ethnography of “good politics”, even if it needed qualification to address questions of race and gender: Within the game of “good politics”, successful identity-appropriation requires successful self-appropriation.

David knew the Bullshit Jobs book (2018) was fluffy, by the way. His paper-thin pride (and the material conditions of production) would never let him admit it on social media, but to me in private he called it his sell-out book. Simon and Schuster offered a pretty penny and he took it, as he wanted to be able to finally buy a house (in London …) instead of renting into his sixties. We can be smug about this, or acknowledge that he was searching for a sense of economic security that many who criticize him already enjoy.

I could see the frustration of David’s double-bind, wherein many political activists derided him as an establishment man, while for many academics his credential as a scholar was weakened by his political engagements. It especially annoyed David that people called him an “anarchist anthropologist”, as if having a political interest in anarchism should qualify his status as an anthropologist. In many ways fame did not treat David well. We could say he got pulled this way and that. Meanwhile, the Pirates book and the Sacrifice book both got pushed down the line by the forthcoming Wengrow book. It’s the Pirates book I always wanted to see. David was always so happy when talking about Madagascar.

Whether you are a fan, or simply feeling curious or generous to Graeber upon his death, please do read his book on magic and slavery in Madagascar, Lost People (2007). He lost a decade and his youth – including his godforsaken working-class teeth, as all who knew him will remember, pouring every resource into that ethnography, yet it is little read. Partly because he fought so hard to publish it at 486 pages. He was proud of his dissertation research, and this literary ethnography (he was reading Dostoevsky when he wrote it – you’ll chuckle) deserves to be appreciated more than some of his popular stuff. I hope now that he is gone, it will be.

I had to leave David, yet still feel terribly sad now knowing our conversation has ended forever. I wanted so much for him to experience more and better happiness, to live long and enjoy the fruits of so much labour, feeling economically secure and self-assured, able to laugh at himself, surrounded by students, interesting characters and friends in a big house full of luxurious snacks. There would be excessive curios and scarves lying about. David was basically the Elvis of anthropology – David, I know that joke would have pissed you off, but it’s hilarious and true and awesome, and from your new digs I trust you can’t take yourself so damn seriously. You’ve finally found the magic.

I wanted more for David, and now can only ask for us to respect him in his passing – whether or not I myself agree with his ideas, he should be known for who he was: He did not agree with the academicization of anarchism (‘anarchist studies’), he felt strongly that anthropology should not give up on reality (objectivity à la ‘critical realism’), he thought both anarchism and anthropology require class analysis, he thought important decisions should be made by consensus, he despised bourgeois operators. Give him a break about the Bullshit Jobs book and read the Madagascar one. David deserves to be remembered for the values he held dear – for rigorous scholarship and for being a kind and silly person, with many redeeming qualities.

References and further reading

Dumont, L. (1970). Homo Hierarchicus. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Graeber, D. (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press

Graeber, D. (2007). Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Indiana: Indiana University Press

Graeber, D. (2009). An Ethnography of Direct Action. NY: AK Press.

Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First Five Thousand Years. NY: Melville House

Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. NY: Simon and Schuster

Lagalisse, E. (2021). Anthropology. In The SAGE Handbook of Marxism. Sara Farris, Beverley Skeggs, Alberto Toscano (Eds.). London: SAGE.

Sahlins, M. and Graeber, D. (2017). On Kings. Chicago: Hau

About the author

Erica Lagalisse

Erica Lagalisse is an anthropologist of social movements. She is a member of The Sociological Review Editorial Board, a popular educator at The Class Work Project, and a visiting fellow at both the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the Anarchism Research Group at Loughborough University. She is known for her book Occult Features of Anarchism: With Attention to the Conspiracy of Kings and the Conspiracy of the Peoples (PM Press, 2019), an intersectional study of anarchist social movements and ethnographic analysis of “conspiracy theory”. Her current research concerns how (even) anarchist activists sometimes recuperate the Black feminist challenge of intersectionality within the realm of neoliberal property relations. Find her at https://lagalisse.net/, at Patreon at https://www.patreon.com/spartacussellsout/, on Instagram @ericalagalisse, on Facebook @ericalagalisse, and on Twitter @ELagalisse.

For the record, I think Bullshit Jobs was brilliant, and not at all fluffy. But I have always found the chapter in which he kinda sorta endorses UBI (but not really) pretty frigging weird. I imagine that is what he must have been referring to if he called it his "sell-out book". Before people judge him, I suggest reading the book, or at least the UBI part, which is right at the end.

To anyone new to Graeber: you absolutely must read between the lines when reading his work. He was closeted conspiracy theorist through-and-through, and he picked his battles. Do I judge him for that? No, because he succeeded in getting his message out there to a wide audience. Disguising some of the radical content of his message was clearly part of how he did that. He snuck all kinds of things past the censors.

Pro tip: don't neglect the footnotes. He dropped plenty of hints in there.

wow!... I guess, I have my reading material sorted out for the next 10 or 20 years.