WE SUPPORT THE STANDARD NARRATIVE!

Why anarchists agree with the Egalitarian Origins Hypothesis, the dominant narrative in anthropology about prehistoric human social organization

HEY NEVERMORONS,

Today is reader appreciation day!

NEVERMORE is not aimed at a general audience. It is for smart people, and the fact that of you are abnormally intellectually well-endowed shows regularly in the comment section.

One such comment, which I'll present as Exhibit A, was left in response to a recent piece about an amazing book by the late great anarcho-mystic Peter Lamborn Wilson (also known as Hakim Bey).

WHAT IS THE SHAMANIC TRACE? (MY MIND IS BLOWN!)

The Effigy Mound builders adopted the idea of the mound from Cahokian/Mississippian Civilization, but they changed the entire meaning of the mounds into a symbolic language that transpires both within Nature and about Nature simultaneously. If it were not for the ravages of time and the Wisconsin dairy industry, we would possess an entire “Koran”, as it…

That book, The Shamanic Trace, includes very interesting speculation on the broadest possible sweep of time that human beings can speak meaningfully about, which is what I call the WORLD-STORY.

A reader going by the name of ebear specifically challenged me on one specific question which is of critical importance, and it just so happy I’ve got a very satisfactory answer to his question! This gives me the opportunity to clarify my thinking, and I’m sure that other people have had the same question.

The statement ebear contested was: “The non-authoritarian hunter/gatherer tribe seems to have been the universal form of human society for 99% of its existence."

He asks:

What leads you to believe this? An examination of existing tribal societies (and those encountered by early explorers) reveals certain common features, such as hereditary chieftains, a warrior caste, shamans, and some form of ancestor worship. Surely these are all indicators of some form of authority? The term 'authoritarian' has an inherent bias, suggesting that authority in and of itself is a bad thing. A better term might be 'organizing principle.' Collective effort, as in hunting and gathering, had to follow some form of organized behaviour to succeed, and it seems logical that the most experienced hunters would be natural leaders, which would entitle them to certain privileges, thus implying some form of authority.

Now, the Right Honourable Mr. Ebear, Esq. is quite correct in this - not all indigenous societies are egalitarian. Far from it. Some have had customs that we would find absolutely abhorrent, and there are countless examples of very patriarchal indigenous societies, many of whom have had gerontocracy as well as patriarchy.

Quite aside - do you ever wonder why feminists don’t ever talk about gerontocracy? If Hutterite society, for instance, young men have no decision-making. One commentator summed up the political role of unmarried men thusly: “You might as well be a woman!” By focusing on only variable - sex - and neglecting other ways in which biology relates to political power, feminists oversimplify how and why decisions get made. If feminists were to criticize Hutterite society for being patriarchal, they would be missing a more critical determinant of decision-making power, which is age. Other factors could include marital status, lineage, clan, physical ability (such as skill in war or hunting), cognitive ability (intelligence), or perceived magical/shamanic power (often conceived of in terms of relation to invisible entities such as ancestors, gods, or totem animals/spirits). All these are important factors in determining whose voice gets listened to, which is ultimately what politics is all about. Feminists go astray when they think that the fact that women haven’t historically been listened to sufficiently as proof that they don’t have to listen to men! Reality don’t work that way, ladies!

CULTURE IS A WAY FOR HUMANS TO ADAPT TO THEIR ENVIRONMENTS

However, none of this invalidates the egalitarian origins hypothesis, and I’m going to explain why. I will do this using the standard narrative of human origins, because for once I’m not against the dominant narrative… (!)

I think that mainstream anthropology is totally right that culture is a way of adapting to environmental conditions. That’s what makes indigenous cultures indigenous: they are adapted to their environments.

I will favour this approach because Mr. Ebear is a big fan of Marvin Harris, O.G. Grand Poobah of Cultural Anthropology, leading me to believe that he will favour materialist explanations. I personally believe in animism and favour a non-anthropocentric view of the energetic matrix we are apart of, but I like to move back and forth across the boundaries of the rational domain. For my purposes here, I’ll colour between the lines of rationalism.

WHAT IS REVOLUTIONARY SANITY?

(Another aside on nomenclature. Confusingly, materialism has a specific meaning in anthropology. Basically cultural anthropologists believe that different cultures are different ways that humans create in response to material conditions. If bringing a banana in a boat regularly causes bad luck, for instance, a given culture may come up with a taboo against bringing bananas on boats, as is common amongst lobstermen in the Maritimes (which I learned about the hard way!).

I am opposed to materialism in the vernacular sense - the Darwinian-Marxist idea that consciousness comes from matter, which I associate with determinism, reductionism, and eugenics. I’m absolutely not at all against cultural materialism, which is perhaps best thought of as sanity. If it were up to me, I would prefer to use a different term for the sake of clarity, but there are are a lot of things I would change about our political vocabularies if it were up to me. But if I didn’t think that material conditions were importance, I wouldn’t have dedicated my life to environmental activism. Political sovereignty is impossible without food sovereignty, and food sovereignty is impossible without an intact land base. Eventually I will clarify the difference between scientific materialism and cultural materialism when I get around to elucidating my theory of Revolutionary Sanity, which is part of my strategy to pitch anarchism in a way that will appeal equally to Volvo-driving soccer moms, proletarian urbanites, and Latin American campesinos.)

Because Mr. Ebear’s comment is so thought-provoking, I will share the whole thing:

"Moreover, since Sahlin’s paradigm-shift, a great mystery hovers around the question of agriculture. Namely:—What on earth could induce any sane person to give up hunting and gathering (four hours daily labor or less, 200 or more items in the “larder”, “the original leisure society”, etc.) for the rigors of agriculture (14 or more hours a day, 20 items in the larder, the “work ethic”, etc.)?"

I don't regard this as any great mystery, and I believe Marvin Harris adequately addressed the problem in "Cultural Materialism." Hunting and gathering is risky business and has no guarantee of success, so characterizing it as four hours a day of easy effort sounds like the thoughts of someone who's never actually hunted for their food. Bear in mind, many hunter-gathers had to follow herds. That meant they often had to pick up and move at a moment's notice. They were also subject to natural disaster, among them grass or forest fires, which would drive away game, or kill them and possibly the tribe as well. On the gathering side, women had to range further afield as the season progressed, since the nearby early picking would become depleted. This exposed them to predators, often without the protection of men who were by necessity off hunting. No doubt a lot of children were lost this way, which would be highly demoralizing.

Under such circumstances, once someone noticed that seeds dropped along the way grew into the same plants you had to travel distance to find, it was logical to plant them closer to home, thus the beginning of agriculture. This doesn't work too well if you're nomadic unless you have established seasonal camps, but that would often be the case, and the seeds you planted the year before would be fully grown when you returned.

Speaking of herds, once you had the idea of planting seeds for easy access, it couldn't have been too long before the same idea was applied to herds. Why follow them around when you can capture their young, enclose them and breed them? So animal husbandry is the natural outcome of primitive agriculture, and the two are intimately entwined in everything that follows.

With enclosure comes the need for defence, first against predators, later against hostile tribes who adopt plunder as a survival strategy. Fortunately the skills of the hunter are the same as the warrior, so a caste emerges whose task is primarily defence of the settlement, while others tend to the herds or to the fields. So there's your early social division giving rise to hierarchy and some form of authority, based on handed down knowledge. You don't get to be an authority for very long unless your ideas actually work.

As for the 'the rigors of agriculture' again, spoken like someone who's never farmed. There are two busy periods in agriculture, preparing and planting, followed by harvesting and processing. Between the two there's not a lot to do, other than chase off vermin. Success depends on a good harvest that will get you through winter of course, supplemented by hunting winter game, but other than that there's not much work other than keeping the paths clear of snow, the wood for fires having already been gathered in sufficient amount.

Speaking of winter, there's good reason to believe that it fostered the growth of intelligence in our species. The reason is fairly simple. You have to plan ahead if you're going to survive harsh winters, so this creates an evolutionary bias that selects for foresight. No such bias exists in sunnier regions where food is abundant on a year-round basis. This partially explains the rise of advanced civilization in colder climes. Warmer climes with advanced civilizations almost universally appear around river estuaries where irrigation became the dominant organizing principle. The Indus, Nile, Euphrates, Ganges, Yangtze, etc. Grist for a future mill.

Back to the herds, specifically cows and horses. Many reasons are put forth for the collapse of Pre-Colombian civilizations. The strongest argument I've heard is that they lacked cows and horses. With cows you get draft animals thus plowed fields, leading to surplus. You also get a steady supply of meat and fresh milk. With horses you get a draft animal for transportation and defence. Properly managed, this allows for expansion of your domain as the population increases as a result of abundant food leading to better nutrition, along with more free time to devote to chasing tail. Don't let anyone tell you that hunting and gathering is easier than agriculture. It just isn't true or we'd all still be doing it.

So, in the absence of horses and cows, pre-Colombian civilization reached a Malthusian limit of growth and either reverted to cannibalism (Aztecas) or the people wandered off and reverted to earlier hunter-gatherer forms. The Mayans didn't disappear - I've met many of them and can tell you they're most definitely still there. Great people too BTW. They just couldn't sustain the level of civilization they achieved without cows and horses and so reverted to the mean. Same applies to the Incas. They had llamas, but if you've ever met a llama you know they're no good as draft animals, and that is the crucial point where societies transition from enslavement of people to enslavement of animals. Cats, and dogs fall in this category as well. Cats to keep rodent away from your grain, dogs to protect against predators and assist in hunting.

Proof of concept exists in the rapid emergence of the Plains Indian horse culture, as exemplified by the Lakota people. Horses that escaped the Spanish formed wild herds that were quickly domesticated by the native tribes that followed the buffalo. The advantages were obvious. No more risky hunting on foot, or driving buffalo over cliffs which was wasteful and diminished the herd. Now you could just ride along side and pick them off in sufficient amounts. Also, when it came time to move, the horses doubled as draft animals. The arrival of the Spanish had a profound effect on the plains cultures, most of whom never met a single Spaniard. Just their horses.

Another obvious outcome of enclosure is specialization. Various new tasks emerge with enclosure, and so a division of labour and their attendant hierarchies emerge. Arguably the need for specialization was a determining factor in the emergence of intelligence. I recall a half-joking theory I came across that probably contains a grain of truth. The guy who could chip flint and knew where to find it would likely guard that secret, thus ensuring his status within the tribe. He'd be far too valuable to risk losing in a dangerous hunt, and so stayed behind where he divided his time between chipping arrow heads and boinking the women. Thus his genes got passed on with greater frequency than the hunters. The same was probably true of the guy who knew how to make fire, not to mention the shaman, who might have been one and the same.

I can't stress enough the importance of Marvin Harris' contribution to anthropology. He took the mystery out by looking for the material causes of human behaviour. Most of what I just wrote came from him. Unfortunately I no longer have the book (lent it and never got it back...grrr!) so this is all from memory and apologies for any inaccuracies or omissions

Great comment, Ebear. The rest of you dinguses could really learn something from this guy.

This seems as good a moment as any to throw in a very interesting history lesson about the history of indigenous people in Wisconsin, which is what The Shamanic Trace is about.

Also, do you guys know that Negativland is still making music? Not only that, they’ve somehow gotten even better!!!

Check this shit out - it’s the musical equivalent of Marshall McLuhan overdosing on ketamine!

What? You don’t know who Negativland is? Seriously? They’re like the new Crass! Or at least the new Chumbawamba!

Hmm. Maybe I shouldn’t include so many obscure references to anarcho-punk. I wonder what percentage of my audience are punks. Probably not more than a quarter.

Hmm, maybe I’ll take a poll.

Or better yet, two polls!

Well, in any case, here’s something everyone can enjoy:

WHAT IS THE STANDARD NARRATIVE OF HUMAN ORIGINS?

In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow spend a lot of time and energy critiquing “the standard narrative” about human origins in anthropology. They do so with reference to such mainstream narrative gatekeepers like Jared Diamond, Francis Fukuyama, Yuval Noah Harari, and Stephen Pinker. The only problem with this is that none of the aforementioned authors are anthropologists. They are hardcore statists and flagrant apologists for neoliberalism who have spent their careers arguing that things are the way they are because “them’s the breaks, fool”. Everything they publish justifies the status quo and discourages revolutionary action.

As Dr. Scrotes explains:

[T]he narrative that Graeber & Wengrow spend the early chapters in the book pretending to debunk, isn’t actually a narrative that anyone with any expertise really believes.

It’s a deliberate convenient oversimplification of a much more complicated picture that has all sorts of interesting exceptions and reversals and timelines that are too complicated to explain in a short article or even a book that isn’t specifically about the palaeolithic, or about the origins of inequality.

And the people they keep referring to, Jared Diamond, Noah Hararri, Francis Fukuyama – these aren’t even experts in subjects relevant to human origins, they’re popular writers with expertise in other fields who use the elevator pitch version of the conventional narrative of human origins in order to make points about other things.

This is infuriating, and disingenuous, and it really makes me wonder whether David Graeber actually wrote The Dawn of Everything, which was published posthumously a year after his mysterious sudden death.

How did David Graeber die?

Hey Gang, For the better part of a year, I’ve been pretty obsessed with David Graeber, the anarchist activist best known for his central role in the Occupy Movement. I’ve read three of his books, tons of his articles, watched countless interviews, and listened to a lot of his lectures.

THE STANDARD NARRATIVE IN ANTHROPOLOGY IS THE EGALITARIAN ORIGINS HYPOTHESIS

But anyway, here’s the short answer to your question: our Stone Age ancestors are presumed to have lived in small nomadic bands of hunter-gatherers through the vast majority of our species’ existence.

If you believe in evolution, you believe that we evolved from animals, meaning that we practiced a specific type of subsistence known as immediate-return hunting and gathering. In this form of foraging, food is not stored for later consumption.

The most primitive societies practice immediate-return hunting and gathering, and we know from the anthropological record tend to be egalitarian.

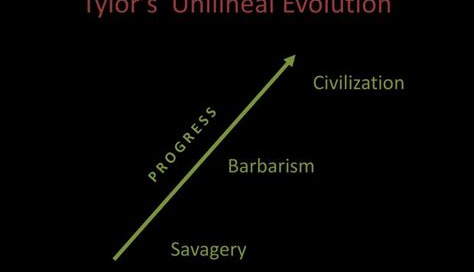

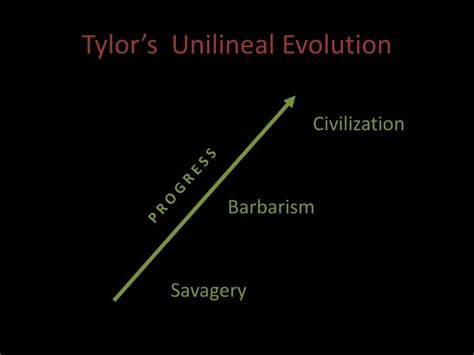

By the way, as politically incorrect as Lewis Henry Morgan’s “stages of evolution” are, mainstream anthropology still does subscribe to cultural evolutionism, because there is a general trend for societies to move from simpler forms of subsistence and social organization to more complex ones.

The simplest societies are primitive, and I think that people should question why it is that they find that term offensive. Complex does not mean good. There are forms of complexification that represent cultural devolution. Everyone hates bureaucractic red tape, for instance. And the most elegant equations in math are also the simplest. Primitivists believe something similar - that the simplest survival strategies are best.

I’m not planning to go to bat for the term primitivism, though, because Darren Allen has proposed an alternative which I prefer.

PRIMIVITISM VS. PRIMALISM - WHICH IS MORE BASED?

Ted Kaczynski, the notorious ‘domestic terrorist’ and radical author (who died last month) also went into the Woods. After he was arrested and his work became widely known, he became, for a short time, the darling of anarcho-primitivists such as John Zerzan, and with good reason, as

Plus, primitivism is associated with John Zerzan and Kevin Tucker, and they don’t seem to want to have anything to do with us.

DOES JOHN ZERZAN UNDERSTAND METAPHYSICS?

HEY FOLKS, A bit more than a year ago, I began publishing a series of critiques of postmodernism under the name THE INSANE STUPIDITY OF ANTI-ESSENTIALISM. I’ll be honest - it began as a way of indirectly critiquing trans ideology. At the time, it was still taboo to point out that one’s biological sex is not a matter of belief, but of fact.

Where evolutionists go wrong is in believing that all change is progress and that human societies proceed only in one direction - towards greater complexity and centralization of power. This is because European intellectuals have traditionally held the view that their culture is superior because civilization allows for the creation of specialized class of professional book-readers, and because intellectuals always are all for higher learning because they tend not to like getting their hands in the dirt.

I’m not hating, by the way - I’m jealous of people who can make money learning things!

Anyway, the standard narrative about human assumes that culture is downstream of subsistence strategies, and that because human beings are pack animals and because evolution has prepared human beings to cooperate because doing so increase our odds of survival. Basically, it’s an evolutionist argument. It is assumed that nature will weed out cultures which fail to adapt to their environments.

Yes, this is somewhat deterministic, and might appear to reduce human agency, but guess what? When we’re talking about the broad sweep of time in the vast amorphous dreamtime of prehistory, the decisions of individuals isn’t what we’re looking at. We’re looking at general tendencies over huge amounts of time.

If you are interested in learning more about why anthropologists believe what they believe about human origins, I highly recommend watching the following two videos, which I will quote from at length.

They’re both worth watching, I absolutely promise you!

First, we know that human beings started out as hunter gatherers – because almost all animals are basically hunter gatherers, which is generally defined as anyone who doesn’t practice agriculture. Homo Sapiens start showing up in the record at about 500-300kya, and evidence for farming as a means of subsistence only starts after we get into the holocene geological era which starts 12000ya, though we do have evidence of failed experiments with subsistence farming going back to 35,000 ya.

There used to be a lot of debate about why farming only shows up after the Holocene begins, but it turns out that it’s probably because there just wasn’t enough carbon dioxide in the atmosphere [i erroneously said nitrogen in the soil in the video!] to support sustained agriculture until the holocene era. And then once there was, when hunter gatherers in different places and times found themselves in conditions where hunting and gathering was no longer sustainable and there weren’t unoccupied places left to migrate to, they now had the option to switch to agriculture instead of the previous options of going to war or dying of starvation.

Now why do we think that humans started out as specifically egalitarian hunter gatherers?

Most hunter gatherers that we know about are more egalitarian than we are, but many still have various forms of inequality like gender inequality or gerontocracy, and some positions of limited authority, while some historical hunter gatherers even have had much more elaborate hierarchies with chiefs, nobility and slaves.

Meanwhile one subset of hunter gatherer societies that we know of are extremely egalitarian and deliberately so. They have all sorts of institutions and practices to make sure to make sure that no one ever accumulates much more property or authority than anyone else. Men and women form gendered organizations to defend their interests and to make sure that the other gender never gets an upper hand, they have no chiefs or authority figures and even adults don’t have much authority over older children.

As anthropologist Camilla Power articulated it recently, they’re not just communists, but anarcho communists. They have a strong sense of individuality and autonomy coexisting with an equality strong social pressure to cooperate and share all their property.

Now these are a minority of the hunter gatherers that we know of. There are only about 6 groups of cultures who fall into that category historically and comprising maybe a couple of dozen ethnic groups in total. The Hadza in the savannah in eastern Tanzania, various Kalahari desert hunter gatherer cultures, various Central African Rainforest Pygmy groups like the Mbuti, the Aka and the Mbendjele, various South Indian Mountain Forest groups like the Nayaka, Paliyan and Hill Pandaram various Malaysian rainforest groups like the Batek and Penan and the historical Montagnais-Naskapi people in the coniferous forests of quebec and Labrador who were hunter gatherers at the time of the Jesuit Relations writings in the 1600s.

So why do we think that most of our early ancestors were like this specific subset of hunter gatherers rather than all like all of the other less egalitarian hunter gatherers that we know of?

We think this, because despite the fact that these egalitarian foragers live in all sorts of geographic areas on different continents, every single one of these cultures practices or practice-d the same type of hunting and gathering economy, which happens to be the type of economy that we believe that most – but not all – of our ancestors practiced until the holocene era, and which maybe all of our earliest ancestors practiced.

And that type of economy is what anthropologist james woodburn called an “immediate return” economy where you hunt and gather and then consume what you collected within a few days without processing it in any elaborate way.

Why do we think our ancestors were mostly immediate return foragers? Again, most animals are basically immediate return foragers, and our closest relatives, bonobos, chimpanzees and gorillas certainly are, so it’s pretty safe to assume that the first homo sapiens were also immediate return foragers as well. And the further back in time we go, the less evidence we have, but most of the evidence that we do have shows that people in the middle palaeolithic, which is where we become humans – seem to have been mostly doing nomadic big game hunting, much like those recent egalitarian hunter-gatherers do.

Anyway, I hope that this answers your question, Mr. Ebear. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

And yeah, this Reader Appreciation Day post is meant to drive engagement. Obviously a comment like his took some mental energy to type out, and I want to encourage people that such effort is worthwhile.

I really do appreciate reader engagement, and not only because it’s a step in the direction of having a thousand true fans, which is probably what I need to achieve in order to make a living writing, which is my goal.

Constructive criticism (and other feedback) help me become a better writer, and more importantly, a better thinker.

So thank you to everyone who takes the time to leave thoughtful comments, and to the paid subscribers who sustain my hope that there are some people in the world who think that what I do is valuable.

As for the rest of you, go fuck yourselves!

This is really terrific stuff. Thank you for doing what you do.

A proud NEVERMORON with a BA in Anthropology, I love what you are doing!