Hey Folks,

As you know, I like to write about taboo.

Partly, this is because taboo topics are fun to write about. But taboos are also a very important subject in anthropology, as they are defining characteristics of different cultures.

Taboos should be of particular interest to anarchists, because as I like to repeat, stateless societies govern themselves by custom and taboo, not laws and rulers. There are thousands of examples of societies without centralized state authority. There are zero examples of societies with no taboos.

For some strange reason, the importance of custom and taboo have yet to be fully realized by anarchist theory. Part of my mission in life is to enshrine these vital concepts in their rightful place. No political imaginary is complete without them.

One thing that I’ve been meaning to write about for some time is the Biblical taboo against eating pork.

A recent post by Kevin Barrett reminded me that writing about this topic was on my to-do list.

After explaining his philosophical reasons for converting to Islam in his mid-30s, he has this to say about Islam’s “minor rules of day-to-day life”, such as the taboos against consuming pork and alcohol.

I quickly discovered that the Qur’an was right about alcohol: Wine has some good and some bad, but the bad outweighs the good. Medical science has now caught up with that view.

But what about pork? Here I can only speculate.

First and most obviously, undercooked pork is threat to health. In an era when people cooked over fires, and often lacked abundant fuel, that was a serious problem.

Pork may also have bad spiritual effects, in part because it tastes exactly like human flesh, or so the cannibals tell us…

Our ancestors were periodically driven by force of circumstance (famines, low-protein environments) to eat human flesh, a shameful and degrading practice that damages the human spirit.

It is refreshingly honest that Mr. Barrett does not claim to know for sure why Mosaic law forbids eating pork. That taboo certainly is a head-scratcher. It seems like a weird move on the part of God to create pigs, which happen to taste insanely delicious, and then forbid humans from eating them.

It reminds me of that famous scene from The Devil’s Advocate, in which Satan says:

"Let me give you a little inside information about God. God likes to watch. He's a prankster. Think about it. He gives man instincts. He gives you this extraordinary gift, and then what does He do? I swear, for His own amusement, His own private, cosmic gag reel, He sets the rules in opposition. It's the goof of all time. Look but don't touch. Touch but don't taste. Taste, don't swallow. And while you're jumpin' from one foot to the next, what is He doing? He's laughin' His sick, fuckin' ass off!

Barrett seems to be suggesting that the Biblical prohibition against eating pork was basically an early health code regulation, but that idea strains credulity. As we all know, pork can be safely prepared.

As for the notion that pork would be prohibited because it tastes too much like human flesh, that’s just bizarre. Is Barrett suggesting that pork was prohibited in order to prevent people from lusting after human flesh?

I guess that’s one explanation, but in my humble opinion there are better ones out there.

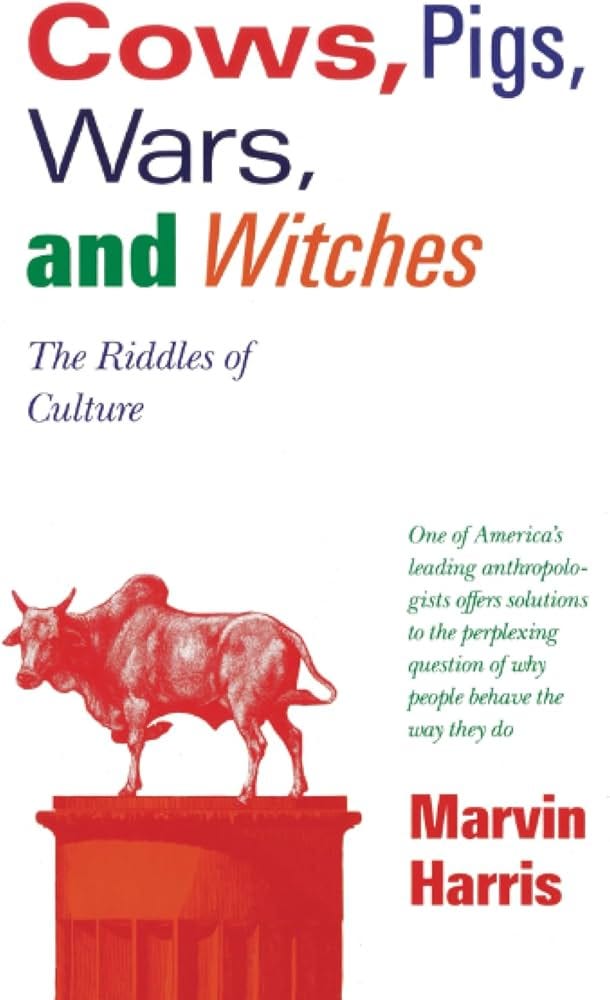

The great anthropologist Marvin Harris was of the firm conviction that the Jewish taboo against eating pork can be explained by understanding the ecological context in which it first arose.

In his brilliant book Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches, Harris pursues a rational explanation for this age-old mystery.

The god of the ancient Hebrews went out of His way (once in the Book of Genesis and again in Leviticus) to denounce the pig as unclean, a beast that pollutes if it is tasted or touched. About 1,500 years later, Allah told His prophet Mohammed that the status of swine was to be the same for the followers of Islam.

Among millions of Jews and hundreds of millions of Moslems, the pig remains an abomination, despite the fact that it can convert grains and tubers into high-grade fats and protein more efficiently than any other animal.

[…]

Why should gods so exalted as Jahweh and Allah have bothered to condemn a harmless and even laughable beast whose flesh is relished by the greater part of mankind? Scholars who accept the biblical and Koranic condemnation of swine have offered a number of explanations.

Before the Renaissance, the most popular was that the pig is literally a dirty animal dirtier than others because it wallows in its own urine and eats excrement. But linking physical uncleanliness to religious abhorrence leads to inconsistencies. Cows and pigs share the same kind of mudhole, yet the cow, too, is a revered symbol of divine grace in many parts of the world.

[…]

Faced with these contradictions, most Jewish and Moslem theologians have abandoned the search for a naturalistic basis of pig hatred. A frankly mystical stance has recently gained favor, in which the grace afforded by conformity to dietary taboos is said to depend upon not knowing exactly what Jahweh had in mind and in not trying to find out.

Harris goes on to note that: “Modern anthropological scholarship has reached a similar impasse”. He disapprovingly quotes Sir James Frazer, the renowned author of The Golden Bough, who declared that pigs, like “all so-called unclean animals, were originally sacred; the reason for not eating them was that many were originally divine.”

This is a theory that I became familiar with through the work of Paul Cudenec, who explains in his masterpiece The Withway that many Greek and Egyptian deities were anthropomorphized versions of plant and animal spirits.

For example, the Greek goddesses Demeter and Persephone are believed to be anthropomorphized representations of corn. Whereas “primitive” people may have worshipped the spirit of corn directly, civilized people apparently came to worship increasingly abstract representations.

It is hard to deny that this theory is compelling! It certainly seems to me that a big part of the problem of the modern world is that people worship abstractions.

It may be hard for modern people to believe that their ancestors once venerated animals, but there is no shortage of anthropological evidence that pre-modern people did precisely that.

The Ainu of Japan venerated bears, Sumatrans venerated tigers, and some tribes from Madagascar apparently venerated crocodiles.

And in the mythologies of many different cultures of Turtle Island, animal spirits occupy the mythological roles played by the Gods in ancient Greece. Whereas the Norse trickster God Loki has a human-like form, the Trickster of Turtle Island is more commonly Coyote or Raven.

I accept Cudenec’s general premise that many ancient deities were anthropomorphized versions of animal spirits. I am less convinced of the specific claim that the Jews did not eat pork because their ancestors once venerated pigs. But let us consider it.

According to Sir Frazer, the Egyptian god Osiris was an anthropomorphized version of the pig. He claims:

“The annual sacrifice of a pig to Osiris, coupled with the alleged hostility of the animal to the god, tends to show, first, that originally the pig was a god, and, second, that he was Osiris. At a later age, when Osiris became anthropomorphic and his original relation to the pig had been forgotten, the animal was first distinguished from him, and afterwards adopted as an enemy to him by mythologists who could think of no reason for killing a beast in connexion with the worship of a god except that the beast was the god’s enemy...”

Regarding the reasons why religious Jews, like Muslims, do not eat pork, he says:

“We must conclude that, originally at least, the pig was revered rather than abhorred by the Israelites... And in general it may perhaps be said that all so-called unclean animals were originally sacred; the reason for not eating them was that they were divine.”

Cudenec finds a parallel here with the taboo on eating horse-flesh in Britain, which was described by Robert Graves.

According to Graves:

“The horse, or pony, has been a sacred animal in Britain from prehistoric times, not merely since the Bronze Age introduction of the stronger Asiatic breed. The only human figure represented in what survives of British Old Stone Age art is a man wearing a horse-mask, carved in bone, found in the Derbyshire Pin-hole Cave; a remote ancestor of the hobby-horse mummers in the English ‘Christmas Play’. The Saxons and Danes venerated the horse as much as did their Celtic predecessors.”

This leads to an extremely interesting question:

Why do Western Europeans have a taboo against eating horse-flesh?

It is easy to become mystified when one considers the seemingly arbitrary nature of food taboos. As far as I am aware, there is no logical reason why human beings should choose to refrain from eating horse-flesh or dog-meat. This is part of the reason it is hard for me to accept Barrett’s claim that the Jewish taboo on pork is best understood as an ancient health code regulation.

That said, the Western European taboo against eating horse and dog meat is certainly not because we regard those animals as unclean. It is because we love them. Simply put, it feels wrong to eat one’s friends. Is this irrational sentimentality a vestige of our ancient horse-venerating past? If so, is Cudenec suggesting that ancient Brits also worshipped dogs?

At this point, it is interesting to learn that the Catholic taboo against eating horse-flesh stems from the 8th century, when Pope Gregory III explicitly condemned the practice.

Apparently Germanic tribes, which traditionally revered horses, sometimes consumed horse meat in religious ceremonies. As Christianity expanded further into the German homeland, the Church sought to suppress these practices. By declaring horse-eating sinful, the Church distinguished Christian converts from their pagan past.

However, the Catholic Church has never prohibited the consumption of dog meat or cat meat. Yet the mere idea of eating cat meat is enough to make many Europeans gag.

As everyone knows, however, this taboo is not universal. In China, it is perfectly normal to eat cats and dogs. To the Chinese, our horror at that practice must seem wholly irrational. And when one seeks to justify why it is fine to butcher a lamb but not a horse, one quickly realizes that we are dealing with a very deeply-seated cultural taboo. It’s truly fascinating.

But I digress. We’re not going to solve every riddle of anthropology today. Let’s get back to pigs.

Harris is unconvinced by the argument that the Jewish taboo against eating pork is best explained by the theory that ancient Semites once revered pigs.

This is of no help whatsoever, since sheep, goats, and cows were also once worshiped in the Middle East, and yet their meat is much enjoyed by all ethnic and religious groups in the region. In particular, the cow, whose golden calf was worshipped at the foot of Mt. Sinai, would seem by Frazer's logic to make a more logical unclean animal for the Hebrews than the pig.

Other scholars have suggested that pigs, along with the rest of the animals tabooed in the Bible and the Koran, were once the totemic symbols of different tribal clans. This may indeed have been the case with sheep, goats, and cows, which were the staple diet of the tribal pastoralists who inhabited the river valleys of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Until their conquest of the Jordan Valley in Palestine, beginning in the thirteenth century B.C., the Hebrews were nomadic pastoralists, living almost entirely from herds of sheep, goats, and cattle. Like all pastoral peoples they maintained close relationships with the sedentary farmers who held the oases and the great rivers. From time to time these relationships matured into a more sedentary, agriculturally-oriented lifestyle. This appears to have been the case with Abraham's descendants in Mesopotamia, Joseph's followers in Egypt, and Isaac's followers in the western Negev. But even during the climax of urban and village life under King David and King Solomon, the herding of sheep, goats, and cattle continued to be a very important economic activity.

The Ecological Argument

Harris then proceeds to make a powerful case that the reason for the Jewish taboo against consuming pork was for solid ecological reasons.

Within the overall pattern of this mixed farming and pastoral complex, the divine prohibition against pork constituted a sound ecological strategy. The nomadic Israelites could not raise pigs in their arid habitats, while for the semi-sedentary and village farming populations, pigs were more of a threat than an asset.

The basic reason for this is that the world zones of pastoral nomadism correspond to unforested plains and hills that are too arid for rainfall agriculture and that cannot easily be irrigated. The domestic animals best adapted to these zones are the ruminants cattle, sheep, and goats. Ruminants have sacks anterior to their stomachs which enable them to digest grass, leaves, and other foods consisting mainly of cellulose more efficiently than any other mammals. The pig, however, is primarily a creature of forests and shaded riverbanks. Although it is omnivorous, its best weight gain is from food low in cellulose-nuts, fruits, tubers, and especially grains, making it a direct competitor of man. It cannot subsist on grass alone, and nowhere in the world do fully nomadic pastoralists raise significant numbers of pigs. The pig has the further disadvantage of not being a practical source of milk and of being notoriously difficult to herd over long distances.

Above all, the pig is thermodynamically ill-adapted to the hot, dry climate of the Negev, the Jordan Valley, and the other lands of the Bible and the Koran. Compared to cattle, goats, and sheep, the pig has an inefficient system for regulating its body temperature. Despite the expression "To sweat like a pig," it has recently been proved that pigs can't sweat at all. Human beings, the sweatiest of all mammals, cool themselves by evaporating as much as 1,000 grams of body liquid per hour from each square meter of body surface. The best the pig can manage is 30 grams per square meter. Even sheep evaporate twice as much body liquid through their skins as pigs. Sheep also have the advantage of thick white wool that both reflects the sun's rays and provides insulation when the temperature of the air rises above that of the body. According to L. E. Mount of the Agricultural Research Council Institute of Animal Physiology in Cambridge, England, adult pigs will die if exposed to direct sunlight and air temperatures over 98° F. In the Jordan Valley, air temperatures of 110° F. occur almost every summer, and there is intense sunshine throughout the year.

To compensate for its lack of protective hair and its inability to sweat, the pig must dampen its skin with external moisture. It prefers to do this by wallowing in fresh clean mud, but it will cover its skin with its own urine and feces if nothing else is available. Below 84° F., pigs kept in pens deposit their excreta away from their sleeping and feeding areas, while above 84° F. they begin to excrete indiscriminately throughout the pen. The higher the temperature, the "dirtier" they become. So there is some truth to the theory that the religious uncleanliness of the pig rests upon actual physical dirtiness. Only it is not in the nature of the pig to be dirty everywhere; rather it is in the nature of the hot, arid habitat of the Middle East to make the pig maximally dependent upon the cooling effect of its own excrement.

Sheep and goats were the first animals to be domesticated in the Middle East, possibly as early as 9,000 B.C. Pigs were domesticated in the same general region about 2,000 years later. Bone counts conducted by archaeologists at early prehistoric village farming sites show that the domesticated pig was almost always a relatively minor part of the village fauna, constituting only about 5 percent of the food animal remains. This is what one would expect of a creature which had to be provided with shade and mudholes, couldn't be milked, and ate the same food as man.

As I pointed out in the case of the Hindu prohibition on beef, under preindustrial conditions, any animal that is raised primarily for its meat is a luxury. This generalization applies as well to preindustrial pastoralists, who seldom exploit their herds primarily for meat.

Among the ancient mixed farming and pastoralist communities of the Middle East, domestic animals were valued primarily as sources of milk, cheese, hides, dung, fiber, and traction for plowing. Goats, sheep, and cattle provided ample amounts of these items plus an occasional supplement of lean meat. From the beginning, therefore, pork must have been a luxury food, esteemed for its succulent, tender, and fatty qualities.

Between 7,000 and 2,000 B.C., pork became still more of a luxury. During this period there was a sixtyfold increase in the human population of the Middle East. Extensive deforestation accompanied the rise in population, especially as a result of permanent damage caused by the large herds of sheep and goats. Shade and water, the natural conditions appropriate for pig raising, became progressively more scarce, and pork became even more of an ecological and economic luxury.

As in the case of the beef-eating taboo, the greater the temptation, the greater the need for divine interdiction. This relationship is generally accepted as suitable for explaining why the gods are always so interested in combating sexual temptations such as incest and adultery. Here I merely apply it to a tempting food. The Middle East is the wrong place to raise pigs, but pork remains a succulent treat. People always find it difficult to resist such temptations on their own. Hence Jahweh was heard to say that swine were unclean, not only as food, but to the touch as well. Allah was heard to repeat the same message for the same reason: It was ecologically maladaptive to try to raise pigs in substantial numbers. Small-scale production would only increase the temptation. Better then, to interdict the consumption of pork entirely, and to concentrate on raising goats, sheep, and cattle. Pigs tasted good but it was too expensive to feed them and keep them cool.

Many questions remain, especially why each of the other creatures interdicted by the Bible-vultures, hawks, snakes, snails, shellfish, fish without scales, and so forth came under the same divine taboo. And why Jews and Muslims, no longer living in the Middle East, continue-with varying degrees of exactitude and zeal-to observe the ancient dietary laws. In general, it appears to me that most of the interdicted birds and animals fall squarely into one of two categories. Some, like ospreys, vultures, and hawks, are not even potentially significant sources of food. Others, like shellfish, are obviously unavailable to mixed pastoral-farming populations. Neither of these categories of tabooed creatures raises the kind of question I have set out to answer--namely, how to account for an apparently bizarre and wasteful taboo. There is obviously nothing irrational about not spending one's time chasing vultures for dinner, or not hiking fifty miles across the desert for a plate of clams on the half shell.

This is an appropriate moment to deny the claim that all religiously sanctioned food practices have ecological explanations. Taboos also have social functions, such as helping people to think of themselves as a distinctive community. This function is well served by the modern observance of dietary rules among Muslims and Jews outside of their Middle Eastern homelands. The question to be put to these practices is whether they diminish in some significant degree the practical and mundane welfare of Jews and Muslims by depriving them of nutritional factors for which there are no readily available substitutes. I think the answer is almost certainly negative. But now permit me to resist another kind of temptation--the temptation to explain everything.

Well, there you have it, folks. I think that that is the most parsimonious explanation for the Jewish taboo against eating pork.

So did ancient Jews worship pigs? I’m going with no. Sir James Frazer was surely onto something with his theory about how Greek gods were anthropomorphized versions of animal spirits, but I think he took his conjecture several steps too far when it comes to the supposed Semitic veneration of pigs.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments!

for the unmediated worship of that which is beyond all abstraction,

crow qu’appelle

Utterly fascinating. Thank you. I learned a lot