Dear Nevermorons,

Not long ago, I declared war on Darwinism.

In the past two week, I’ve published four critiques of the theory that claims that the only possible explanation for the existence of birds is that fish learned to fly through a series of random mutations.

I think it’s going pretty swimmingly, although I am disappointed no Darwinist zealots have deigned me worthy of their righteous rage. It would be fun pummelling them back into the primordial ooze.

If you’ve been following my work, you are surely having doubts about Darwin’s theory by now. If you’re like me, however, it will take you some time that you were so thoroughly duped by the Darwinist delusion.

Just last year, I was cranking out pieces that took “the Theory of Evolution” as a proven scientific fact.

It wasn’t until I learned that Karl Popper declared Darwinism to be an unfalsifiable “metaphysical research programme” way back in 1974 that I started seriously considering the possibility that Darwinism might nothing but a bunch of bullcrap. You know, like virology.

Fast forward a year, and there’s no longer any question in my mind. Darwinism is bunk. And if you’re a reasonably intelligent person with an open mind, I have the utmost confidence that you will come to the same conclusion I have. If you take the time to look into, that is.

My advice is this: Take some time to let this all sink in. Don’t be afraid. A short time ago, I was just like most of you. I’d spent my my entire adult life believing that fish somehow learned to fly.

We all strive to be consistent in our beliefs, and I don’t expect you to convert to creationism overnight. I just ask that you keep this in mind - letting go of false beliefs is only scary until you do it. And after you do it, you feel freer.

But I know what you’re thinking - how could so many smart people be wrong about Darwinism for so long? It’s a great question, and the answer is simple. For over 150 years, Darwinism been promoted by the Establishment, which includes academia as well as the mainstream media. There have always been dissenters, but they are treated as kooks by “the experts”.

A favourite trick is to portray all dissenters as Christian fundamentalists who literally believe that the Earth was created in six days and that elephants only survived the Flood thanks to Noah.

If you want to understand the Darwinist deception, it is not sufficient to study scientific evidence (or lack thereof). One must also learn about the history of how it came to be accepted as the dominant paradigm. The good news is that that history is quite fun to learn about.

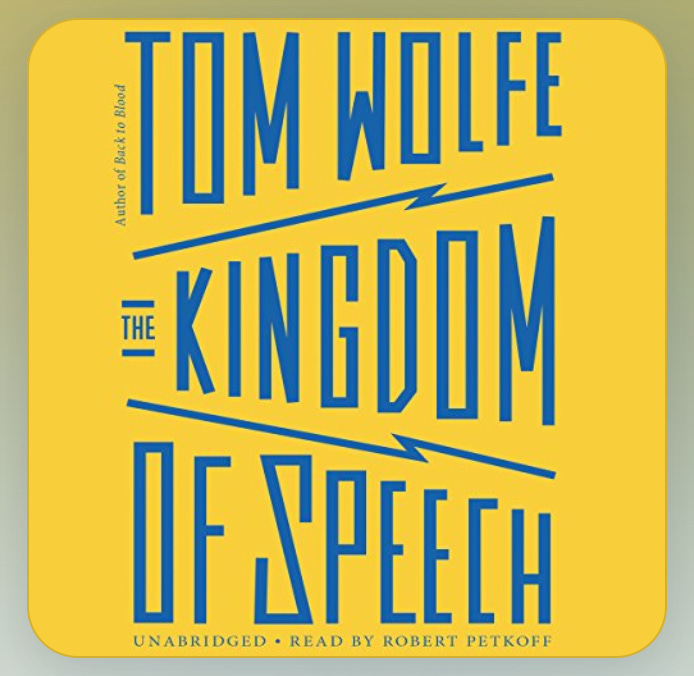

Case in point: Tom Wolfe’s masterpiece The Kingdom of Speech, which merrily rips Darwinism to shreds. Yep, you heard that right. I’m talking about Tom Wolfe, the guy who immortalized the Merry Pranksters in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

If you want to understand Darwinism and don’t mind wading through jargon-laden lawyerly logic, I recommend reading Darwin on Trial by Phillip E. Johnson.

But if you want to understand Darwinism without breaking a sweat, you cannot possibly do any better than reading The Kingdom of Speech. Or better yet, listen to it. The audiobook version is just four and a half hours long, and every minute is riveting.

The Genesis of an Epic Delusion

Today, I’m going to present an abridged selection from Wolfe’s masterful work that will help you understand the genesis of the Darwinist project.

It is important to note that what I calling Darwinism is formally known as the Darwin-Wallace Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection. The theory is attributed to both Charles Darwin and another British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace, who later renounced the theory as inadequate.

I want to call your attention to the fact that Darwin’s ideas did not emerge fully formed from his imagination. Ideas about evolution had already been kicking around for more than fifty years when Darwin stamped his name on “THE Theory of Evolution” (as if there could only be one).

Tellingly, both Darwin and Wallace credited the fun-loving party animal Thomas Malthus as a major inspiration. If you know who Malthus was, that should speak volumes.

The Father of Depopulation

Thomas Malthus is known as “the Father of Population Studies”, but I think of him more as the Father of Depopulation, as he was a major inspiration to eugenists.

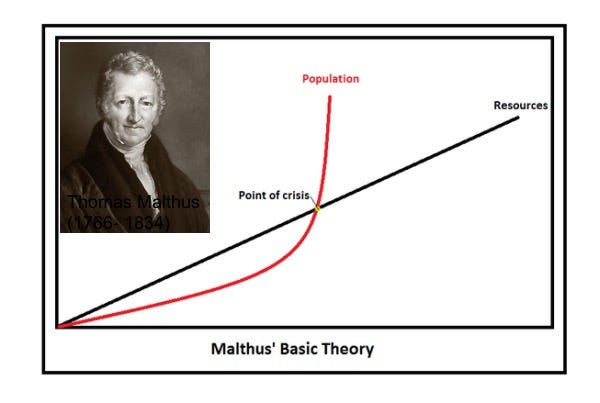

In his major work, Malthus purported to mathematically prove that population growth would always outpace food production, meaning that poverty was an insoluble problem. This came as a huge relief to those members of the ruling class who were concerned about the rising tide of scientific utopianism. If poverty was an insoluble problem, what kind of an idiot would try to solve it?

In those days, people apparently found this graph extremely compelling.

The ideas of Thomas Malthus went on to greatly influence eugenicists and social engineers who sought to manage human populations in previously-undreamt-of ways. But that’s a story for another day. The important point here is that Malthus was a major influence on Darwinism.

Anyway, it seems that Darwin was in the right place at the right time. The paradigm shift he was proposing would have never have gained acceptance were it not for certain earlier developments that made England’s intellectual climate ripe for it. Chief among those developments was another paradigm shift which had occurred a generation earlier.

This is hard to believe now, but just two hundred years ago, the world’s best-educated people believed that the Earth was about six thousand years old or so. That all changed when the British geologist Charles Lyell convinced the scientific world that the world was actually much, much older.

Clearly, six thousand years is not enough time for fish to learn to fly through a series of random mutations.

If you ask me, a hundred billion years probably isn’t enough time either, but that’s just me. But if you’re willing to accept the premise that, given enough time, the scales of fish can become the feathers of birds… well, you kind of need a lot of time.

I encourage you to take some time to really think about the question of the age of the Earth. In the 1700s, Sir Isaac Newton, arguably the greatest scientist of all time, estimated that the Eart was about six thousand years old. Scientists now claim that the Earth is 4.54 billion years old. Think about that. That’s how rapid and radical a paradigm shift can be. Somehow, Lyell convinced an entire generation that the Earth was more than a million times older than their parents had believed. That’s quite the feat.

Oh, by the way, did I mention that Sir Charles Lyell was Charles Darwin’s mentor? I didn’t? Well, he was. If it wasn’t for Lyell, no one today would even have heard of Darwin.

Ah, screw it, I’ll just let Tom Wolfe tell the story. But before I send you on your way, I’ll make you a handy-dandy timeline so you can keep everything straight. This is important, because if you want to understand Darwinism, you have to study its history, not only its extraordinary claims.

A Timeline of How Darwinism Conquered the World

1795 - Scottish geologist James Hutton publishes Theory of the Earth, which proposes the theory of uniformitarianism, which proposed that the Earth was shaped by slow, continuous processes—like erosion, sedimentation, and volcanic activity—over immense periods of time. This stood in direct contrast to the dominant idea of the time, catastrophism, which held that Earth's features were shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events (e.g., floods or divine acts).

1798 - Anglican priest Thomas Robert Malthus publishes An Essay on the Principle of Population. This treatise purported to mathematically prove that population growth would always outpace food production, meaning that poverty was an insoluble problem.

1804 - Jean-Baptiste Lamarck publishes Philosophie Zoologique (Zoological Philosophy). In this seminal book, Lamarck presented one of the earliest comprehensive theories of evolution, proposing that organisms could acquire traits during their lifetimes and pass these traits on to their offspring—a concept now known as Lamarckism.

1830-1833 - The British geologist Charles Lyell publishes Principles of Geology, which came out in three volumes. In this work, Lyell advocated for uniformitarianism—the idea that the Earth's features were shaped by continuous and consistent processes over vast periods of time. This provoked a major paradigm shift by challenging the commonly accepted age of the Earth, which was then believed to be approximately 6,000 years old. This paradigm shift laid the groundwork for Darwin’s theory, which requires vast spans of time for small, gradual changes to produce millions of distinct species.

1844 - A hugely popular book called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation is published anonymously in England. Drawing on Lamarck, it was the first to present a comprehensive narrative of cosmic and biological evolution to the general public. By integrating ideas from astronomy, geology, and biology, Chambers proposed that natural laws governed the development of the universe and life, challenging the prevailing belief in divine intervention. The book sparked widespread debate and controversy in Victorian society, influencing public opinion and further setting the stage for later evolutionary theories. Many years later, it was revealed to be the work of a newspaper publisher named Robert Chambers.

1858 - British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, working in Southeast Asia, writes a paper about natural selection. He mails it to Darwin, requesting that Darwin forward it to Charles Lyell.

1858 – Scientific papers written by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace are presented Linnean Society of London. This marks the public debute of the Darwin-Wallace theory of evolution by natural selection, more commonly known as Darwinism or “the Theory of Evolution”.

1859 – Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species, providing extensive evidence for evolution by natural selection. The full title is On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

1860 - Thomas Henry Huxley, a.k.a. “Darwin’s Bulldog” writes five long, enthusiastic reviews of The Origin of Species in major journals (Macmillan’s Magazine, The Medical Circular, The Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, and The Westminster Review). This goes a long well towards making Darwin’s theory respectable.

1860 – A heated debate occurs at the Oxford University Museum between Huxley and the Anglican Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. Huxley must have mopped the floor with Wilberforce, because Darwinism subsequently became much more popular.

1863 - T.H. Huxley publishes Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature, the first book to systematically argue for human evolution from a common ancestor with apes.

1863 - Charles Lyell publishes The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man in 1863, which endorses Darwin’s theory. In it, he presents geological and archaeological evidence, such as flint tools found alongside extinct animal fossils, to argue that humans have existed far longer than previously believed.

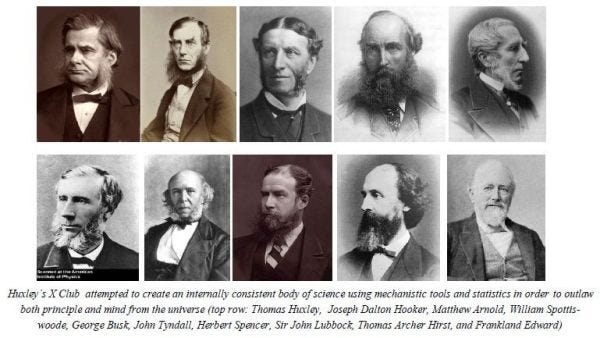

1864 - T.H. Huxley founds the X Club with eight other prominent scientists. This informal dining club aimed to promote Darwinism and to oppose religion. This group was massively successful at stacking university faculties with Darwinists.

1869 - Darwinists found the scientific journal Nature, which is still regarded as one of the world’s most prestigious journals today.

1871 – Darwin publishes The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, which introduces the concept of sexual selection to account for natural phenomena that could not be plausibly explained by natural selection.

1882 - Horrified by the philosophical implications of Darwinism, Friedrich Nietzche announces the death of God and predicts that the 20th century will be characterized by wars more brutal than ever that have come before.

Okay, that ought to be enough to send you down the rabbit hole. Let’s get to the fun part!

Ladies and gentlemen, prepare yourselves for the Tom Wolfe experience!

for the wild,

Crow Qu’appelle

The Kingdom of Speech

Our story begins inside the aching, splitting head of Alfred Wallace, a thirty-five-year-old, tall, lanky, long-bearded, barely grade-school-educated, self-taught British naturalist. He was off—alone—studying the flora and fauna of a volcanic island in the Malay Archipelago near the equator when he came down with the dreaded Genghis ague (rhymes with “bay view”), today known as malaria.

So here he is, in little more than a thatched hut, stretched out, stricken, bedridden, helpless... and another round of the paroxysms strikes with full force: the chills, the rib-rattling shakes... the head-splitting spike of fever followed by a sweat so profuse it turns the bed into a sodden tropical bog.

This being 1858, on a miserable, sparsely populated speck of earth somewhere far, far south of London’s nobs, fops, top hats, and toffs, he has nothing with which to while the time away except for a copy of Tristram Shandy he has already read five times—that and his own thoughts...

One day, he’s lying back on his reeking bog of a bed... thinking... about this and that... when a book he read a good twelve years earlier comes bubbling up his brain stem: An Essay on the Principle of Population by a Church of England priest, Thomas Malthus.

The priest had a deformed palate that left him with a speech defect, but he could write like a dream. The book had been published in 1798 and was still very much alive sixty years and six editions later. Left unchecked, Malthus said, human populations would increase geometrically, doubling every 25 years, while food production would only grow arithmetically.

Left unchecked, Malthus said, human populations would increase geometrically, doubling every twenty-five years. But the food supply increases only arithmetically, one step at a time. By the twenty-first century, the entire earth would be covered by one great heaving mass of very hungry people pressed together shank to flank, butt to gut. But, as Malthus predicted, something did check it—namely, Death, unnatural Death in job lots... starting with starvation, vast famines of it... disease, vast epidemics of it... violence, mayhem, organized slaughter, wars and suicides and gory genocides... to the cantering hoofbeats of the Four Horsemen culling the herds of humanity until but a few, the strongest and the healthiest, are left with enough food to survive. This was precisely what happened with animals, said Malthus.

Abura! It lights up Wallace’s brainpan with a flash—Iz!—the solution to what naturalists called “the mystery of mysteries”: how Evolution works! Of course! Now he can see it! Animal populations go through the same die-offs as man. All of them, from apes to insects, struggle to survive, and only the “fittest”—Wallace’s term—make it. Now he can see an inevitable progression. As generations, ages, eons go by, a breed has to adapt to so many changing conditions, obstacles, and threats that it turns into something else entirely—a new breed, a new species!—in order to survive.

For at least sixty-four years British and French naturalists, starting with the Scotsman James Hutton and the Englishman Erasmus Darwin in 1794 and the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in 1800, had been convinced that all the various species of plants and animals of today had somehow evolved from earlier ones. In 1844 the idea had lit up the sky in the form of an easy-to-read bestselling book called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a complete cosmology of the creation of earth and the solar system and plant and animal life from the lowliest forms up through the transmutations of monkeys into man. It transfixed readers high and low—Alfred, Lord Tennyson; Gladstone, Disraeli, Schopenhauer, Abraham Lincoln, John Stuart Mill; and Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (who read it aloud to each other)... as well as the general public—in droves.

There was no author’s name on the cover or anywhere in its four hundred pages. He or she—there were those who assumed a writer this insidious must be a woman; Lord Byron’s too-clever-by-half daughter Ada Lovelace was one suspect—apparently knew what was coming. The book and Miss, Mrs., or Mr. Anonymous caught Holy Hell from the Church and its divines and devotees. One of the pillars of the Faith was the doctrine that Man had descended from Heaven, definitely not from monkeys in trees. Among the divines, the most ferocious attack was the Reverend Adam Sedgwick’s in the Edinburgh Review. Sedgwick was an Anglican priest and prominent geologist at Cambridge. If words were flames, Sedgwick’s would have burned the anonymous heretic at the stake. The miserable creature gave off the stench of “inner deformity and foulness.” His mind was hopelessly twisted with “gross and filthy views on physiology,” if indeed he still had a mind. The foul wretch thought that “religion is a lie” and “human law a mass of folly, and a base injustice,” and “morality is moonshine.” In short, this disgusting apostate thought “he can make man and woman far better by the help of a baboon” than by the mercies of the Lord God.

Then the book caught hell from the ranks of established naturalists in general. They found it journalistic and amateurish; which is to say, the work of an unknown outsider and a threat to their status. The boy wonder of the “serious” scientific establishment, Thomas Henry Huxley, then twenty-eight, wrote what was later described as “one of the most venomous book reviews of all time” when the tenth edition came out in 1853. He called Vestiges “a once attractive and still notorious work of fiction.” As for its anonymous author, he was one of those ignorant and superficial people who “indulge in science at second-hand and dispense totally with logic.” Everyone in the establishment was happy to point out that this anonymous know-it-all couldn’t begin to explain how, through what physical process, all this transmutation, this evolution, was supposed to have taken place.

Nobody could figure it out—until now, a few moments ago, inside my brain! Mine! Alfred Russel Wallace’s!

He is still in his wet, reeking bed, trying to endure the endless malarial paroxysms, when another kind of fever, an exhilarating fever, seizes him... a fervid desire to record his revelation and show the world—zow! For two days and two nights... during every halfway tranquil moment between the chills, the rattling ribs, the fevers, and the sweats... he writes and he writes writes writes a twenty-plus-page manuscript entitled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type.” He has done it! His will be the first description ever published of the evolution of the species through natural selection. He sent it off to England on the next boat...

...but not to any of the popular scholarly publications, such as the Annals and Magazine of Natural History and The Literary Gazette; and Journal of Arts, Belles Lettres, Sciences, &c., where he had published forty-three papers during his eight years of field work in the Amazon and here in Malay. No, for this one—for it—he was going to mount the Big Stage. He wanted this one to go straight to the dean of all British naturalists, Sir Charles Lyell, the great geologist.

If Lyell found merit in his stunning theory, he had the power to introduce it to the world in a heroic way. The problem was, Wallace didn’t know Lyell. And on this primitive little island, where was he going to get his address? But he had corresponded a few times with another gentleman who was a friend of Lyell’s, namely, Erasmus Darwin’s grandson Charles. Charles had happened to mention in a letter two years earlier, in 1856, that Lyell had praised one of Wallace’s recent articles (probably “On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species,” also known as the “Sarawak Law” paper, 1855).

By early March of 1858, Wallace’s manuscript and a letter were on the ocean, 7,200 miles from England, addressed to Charles Darwin, Esq. Exceedingly polite was that letter. It all but cringed. Wallace was asking Darwin to please read his paper and, if he thought it worthy, to please pass it along to Lyell.

So it was that Wallace put his discovery of all discoveries—the origin of species by natural selection—into the hands of a group of distinguished British Gentlemen. The year 1858 was on the crest of the high Victorian tide of the British Empire’s dominion over palm and pine. Britain was the most powerful military and economic power on earth. The mighty Royal Navy had seized and then secured colonies on every continent except for the frozen, human-proof South Pole. Britain had given birth to the Industrial Revolution and continued to dominate it now, in 1858, almost a century later. She controlled 20 percent of all international trade and 40 percent of all industrial trade. She led the world in scientific progress, from mechanical inventions to advances in medicine, mathematics, and theoretical science.

To give a face to all that, she had at her disposal the most highly polished aristocrat in the West... the British Gentleman. He might or might not have a noble title. He might be a Sir Charles Lyell or a Mr. Charles Darwin. It didn’t matter. Other European aristocrats, even some French ones, lifted their forearms before their faces to shield their eyes in the British Gentleman’s presence. The gleam and refinement of the usual frills—manners, dress, demeanor, tortured accent, wit, and wit’s lacerating weapon, irony—were the least of it. The most of it was wealth, preferably inherited.

The British Gentleman, better known in ages past as a member of the landed gentry, typically lived on inherited wealth upon a country estate of one thousand acres or more, which he rented out for farming by the lower orders. He went to Oxford (Lyell) or Cambridge (Darwin) and might become a military officer, a clergyman, a lawyer, a doctor, a prime minister, a poet, a painter, or a naturalist—but he didn’t have to do anything. He didn’t have to work a day in his life.

Sir Charles Lyell’s ascension to the status of British Gentleman had begun the day his grandfather, also Charles Lyell, converted a naval career into enough money to buy an estate with endless acres and a palatial manor house in Scotland and retire as a high-living lairdly sort who was no longer hobbled socially by the need to work. His erstwhile naval career, which had been a necessity at the time, cast a bit of a shadow upon him, but his son (another) Charles was born free of that curse, and in due course his grandson became Sir Charles Lyell (third Charles in a row), thanks to his achievements in geology. The Darwin line went back much further than that, some two hundred years, to the mid-1600s, to Oliver Cromwell and his sergeant-at-law—Le., lawyer—one Erasmus Earle.

Erasmus Darwin parlayed his position into a small fortune and substantial landholdings, ensuring that, for the subsequent eight or so Earle-Darwin generations, no gentleman needed to work.

Charles Darwin’s father, Robert Darwin, was a doctor—like his father, Erasmus Darwin. His true passion, however, was investing, lending, brokering, betting, and otherwise dealing in the Industrial Revolution’s money markets. He made an absolute fortune, then multiplied it by marrying a daughter of Josiah Wedgwood, one of the early giants of industry. Wedgwood was a potter, a craftsman, who had created factories that produced chinaware finer than any plain potter ever dreamed of. Robert Darwin’s arena was London and its financial district, the City. But like most great British Industrial Revolutionaries, he chose to live in the countryside on a large and largely irrelevant estate—his, in Shropshire, was called the Mount—to show that he was as grand as the landed gentry of yore.

He paid for his son Charles to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh (the boy dropped out), then sent him to Christ’s College at Cambridge to become a clergyman (the boy dropped out), then had to settle for the boy dropping down to the bottom at Cambridge and barely getting a bachelor of arts degree (without honors or the vaguest idea of what to do with his life), and then begrudgingly paid for the boy to enjoy a five-year voyage of exploration, or sightseeing, or something, aboard a boat named for a dog, His Majesty’s Ship Beagle, to prepare him for a career in the field of—as far as Dr. Darwin could tell—nothing. Once the boy was finished with that nonsense, Dr. Darwin, who himself had married a Wedgwood relative, nudged the boy, who was twenty-nine, into marrying in 1839 his perfectly nice, if plain, thirty-year-old spinster first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and in 1842 bought them a country place, Down House, southeast of London, and settled enough money on him for the boy to live well forever and ever.

Living well included eight or nine servants—a butler, a cook, a manservant or two, a parlor maid, a lady’s maid, and at least one nanny and a governess—from day one.

Where did this, the eternally Daddy-paid-for life of a British Gentleman, leave someone like Alfred Russel Wallace? His father, a lawyer, had undertaken a legal career and a business career—and a family and a half, namely, a wife and nine children (Alfred was the eighth)—and wound up swindled and bankrupt, utterly wiped out. The Wallaces were the very picture of what is known today as a downwardly mobile family. They didn’t have the money for Alfred’s education beyond grade school.

Years later, to pay for his explorations in the Amazon and Malay, Wallace had to ship stupendous loads of (dead) snakes, mammals, shells, birds, beetles, butterflies—lots of flamboyant butterflies—moths, gnats, and no-see-um bugs to an agent in England, who sold them to scientists, amateur naturalists, collectors, butterfly lovers, and anyone else intrigued by exotic oddments from the underbellies of the earth. A single shipment might contain thousands of items. The kind of mortal willing or forced by Fate to go out into ankle-sucking muck, brain-frying heat, clouds of mosquitoes, ague-ghastly nightscapes on terrains slithering with poisonous snakes to harvest hundreds of curiosities at a time was called a flycatcher. Gentlemen like Lyell and Darwin didn’t think of flycatchers as fellow naturalists but as suppliers on the order of farmers or cottage weavers.

There you had Alfred Wallace—a flycatcher. The very thought of having to make a living at all, much less as a Malaysian bugmonger, was enough to set any gentleman to itching and scratching all over. And in the mid-nineteenth century, the Gentlemen ran every major area of British life: politics, religion, the military, the arts, and sciences. Wallace was well aware that he was about to get in touch with a social stratum far above his own. But he wasn’t writing Lyell, via Darwin, seeking social acceptance. All he sought was professional recognition by some eminent fellow naturalists.

How very naive of him! The British Gentleman was not merely rich, powerful, and refined. He was also a slick operator...smooth...smooth...smooth and then some. It was said that a British Gentleman could steal your underwear, your smalls and skivvies and knickers, and leave you staring straight at him asking if he didn’t think it had turned rather chilly all of a sudden.

When he received the manuscript and the letter in June of 1858—and please forgive an anachronism, namely, a verb from almost exactly one century later—Mr. Charles Darwin freaked out. He delivered the manuscript to his good friend Lyell, all right... along with a bleating yelp for help. In twenty pages, this man Wallace had forestalled his life’s work—his entire life’s work! “Forestalled” was the 1858 word for “scooped.”

Darwin had achieved a solid reputation among naturalists with a series of monographs about coral reefs, volcanic islands, fossils, barnacles, the habits of mammals... He had written an engaging and highly praised book, Journal of Researches, about his five-year (1831–36) voyage aboard His Majesty’s Ship Beagle, one of England’s many government-sponsored worldwide explorations in the nineteenth century. He had been elected not only to the Geological Society but also to the most prestigious scientific body in England, the Royal Society of London, whose membership was restricted to eight hundred, namely, the eight hundred leading scientists in the world. Fine: and all that meant nothing to him in light of his Theory of Evolution, his very much secret life’s work.

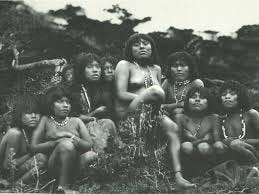

He had started thinking about evolution—“transmutation” was the term for it at the time—when he was on the Beagle. By 1837, a year after the expedition had ended, he was convinced that all plant and animal life on earth was the result of the transmutation, i.e., evolution, of all the various species over millions of years. And not just plants and animals... the Beagle explorers spent long intervals on land, and Darwin kept coming upon natives so primitive they struck a British Gentleman like himself as closer to apes than to humans... particularly the Fuegians. The Fuegians (pronounced “Fwaygians”) were natives of Tierra del Fuego, an Argentine and Chilean province so far south that the tip at the bottom is part of Antarctica. The Fuegians were brown and sun-wrinkled and hairy.

The hair on their heads was as wild as a howling... a howling... well, as a howling hairy ape’s. Their hairy legs were too short and their hairy arms too long for their hairy torsos. In Darwin’s eyes, the only thing that distinguished the Fuegians from the higher apes was the power of speech, if you could call theirs a power. The Fuegian vocabulary was so small, and their grunt-sunken grammar was so simple and simpleminded, it was a rather lame distinction, to Darwin’s way of thinking. He had no idea yet that speech, whether grunted by brutes in the middle of nowhere or intoned by toffs in London, was by far—very far—the greatest power possessed by any creature on earth.

It was after laying eyes on these and other hairy apes below the equator that a blasphemous, mortally sinful, absolutely exciting, fame-flirting, glory-glistening notion stole into Darwin’s head. What if people like the Fuegians weren’t really people but rather an intermediate stage in the transmutation, the evolution, of the ape into... Homo sapiens? That God created man in his own image was a centerpiece of Christian belief. In 1809, when Lamarck had dared to suggest (in Philosophie Zoologique) that apes had evolved into man, it was widely assumed that only his legendary heroism during the Seven Years’ War saved him from serious grief at the hands of the Church and its powerful allies. (Artillery fire had killed more than half of a French infantry company’s men and all its officers. A short, skinny, seventeen-year-old enlisted man, a Private Lamarck, stepped forward and through sheer force of personality assumed command and held the company’s position until reinforcements arrived...)

Darwin was petrified by the prospect of condemnation but aflame with ambition. Seven years later, in 1844, the author of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation felt the same way: so he hid behind the byline Anonymous and never came out. Not even the prospect of fame was enough to overcome his fear. His name was not revealed until the twelfth edition of Vestiges was published in 1884, the book’s fortieth anniversary... thirteen years after the author’s death. Then, at last, the title page bore a byline: Robert Chambers. For all their snobbery, the Gentlemen naturalists proved to have been right. Chambers was not a Gentleman but a journalist, cofounder with his brother, William, of Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal and Chambers’s Encyclopaedia... and an amateur one-shot naturalist.

[…]

It certainly wasn’t scientific experimentation or observation that finally convinced Darwin that man had no special place in the universe. It was a visit to the London Zoo on 28 March 1838, two years after the voyage of the Beagle. One of the zoo’s most popular attractions was an orangutan named Jenny. Jenny had become so accustomed to being around people that many of her reactions were remarkably human. Sometimes she wore clothes. Her gestures, facial expressions, the sounds she made, the way she acted out frustration, mockery, anger, guileless glee, or I-love-you, Help-me! Help-me!, I-want I-want... this last with a whine that made one see how hard she was struggling to put it all into words—it was clear as day! Now Darwin was certain! Jenny was a human being behind the flimsiest of veils. He used his clout as a Gentleman and a leading naturalist to enter Jenny’s cage and study her expressions up close.

Certain he was... and so what? That left him as stumped as everybody else who was so sure about it, including his grandfather Erasmus Darwin. Erasmus couldn’t figure out exactly how transmutation—Evolution—occurred, and neither could his grandson.

In September of 1838, Charles happened to pick up a copy of Thomas Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population... “for amusement,” as he put it, apparently assuming that no deep thinker could possibly find a book as old and popular as Principle of Population profound. He started reading it, and—

Abura! That old Malthusian magic’s got me in its spell! It lit up Darwin’s brainpan precisely the way it would Wallace’s twenty years later—the solution to what naturalists, including Darwin himself until that very moment, called “the mystery of mysteries”: how the littlest creature (or “four or five” of them), smaller even than the smallest invisible biting midge—namely, a cell; never mind those great bulky hares and scorpions and dung-eating beetles—a cell, or a cell and a few brethren, grew up into the most highly developed creature of all, one with a certified Latin name, Homo sapiens.

But what happens to someone like Darwin, who has been honored, who is highly esteemed, who has the highest credentials in his field... when he announces that man is not made in the image of God but is, in fact, nothing but an animal?

He could see, feel, the Church and thousands, tens of thousands, of believers descending upon... me... with the Wrath of God. He was aware of what had happened to Mr. Vestiges, all too aware. It terrified him.

So in the two decades between 1838 — back when he was twenty-nine years old — and 1858, he hadn’t told a soul other than Lyell about his Ahura! moment, and he didn’t even tell Lyell until 1856. For the twenty years before that, his career had been devoted... secretly... to compiling evidence to support what in due course, he calculated, would shake the world: his revelation of the actual origins of man — and, while he was at it, all animals and plants: his Theory of Evolution through natural selection.

He was bringing forth, for all mankind to marvel at... the true story of creation!

Man was not created in the image of God, as the Church taught. Man was an animal, descended straight from other animals, most notably the orangutans.

Darwin was afraid of not one but two things: one, the Wrath of the Godly, and two, some enterprising competitor getting wind of his idea and forestalling him by writing it up himself. And sure enough, up from nowhere pops this little flycatcher Wallace with a scholarly paper, ready for publication, on the evolution of species through natural selection!

He racked his brain to recall whether or not he had written something in a letter that tipped Wallace off. But he couldn’t recall a thing.

Oh, Lyell had warned him... Lyell had warned him... and now all my work, all my dreams — all my dreams —

(Lyell had encouraged Darwin to publish his ideas on evolution before someone beat him to it. This is clear in a letter Darwin wrote to Lyell on June 18, 1858, after receiving Wallace’s paper.)

Then he caught hold of himself. He mustn’t give in to this horrible feeling overwhelming his solar plexus. There was something more important than priority and glory and applause and universal admiration and an awesome place in history... namely, his honor as a Gentleman and a scholar.

He summoned up every tensor of his soul and did what he had to do, and he did it like a man. He dispatched Wallace’s paper to Lyell along with a letter saying:

“It seems to me well worth reading... Please return to me the M.S. which he does not say he wishes me to publish; but I shall of course at once write & offer to send it to any Journal. So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed.”

Coming from the pen of a Gentleman as ever-composed and self-possessed—to-the-point-of-phlegmatic—as Darwin, that word “smashed” rose up from the page like a howl, a howl plus the rizzzppp of those tensors in his soul going haywire and tearing the damned thing to pieces.

What he howled was: “My whole life is about to be smashed and reduced to dust, to a mere footnote to the triumph of another man!”

"Oh, Charlie, Charlie, Charlie..." said Lyell, shaking his head. "Who was it who warned you two years ago about this fellow Wallace? Who was it who told you you'd better get busy and publish this pet theory of yours? ...So why should I even bother, this late in the game?

"But... we are Gentlemen and old pals, after all... and I think I know of a way to get you out of this predicament. It so happens there is a meeting of the Linnean Society, postponed from last month in deference to the death of one of our beloved former Linnean presidents, coming up thirteen days from now, July 1.

"Unfortunately, we don’t have any way to notify Wallace in time, do we? But that’s not our fault. We didn’t schedule the meeting. That’s just the way it goes sometimes. We'll bring our good friend Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, the botanist, in on this. All three of us are on the society’s council. We can make the whole thing seem like the most routine scholarly meeting in the world... the usual learnéd papers learnéd papers learnéd papers, the usual drone drone drone, humm drumm humm...

"The main thing, Charlie, is to establish your priority. We'll present your work and Wallace’s. Now, that’s fair, isn’t it? Even-steven and all that?

"Well, to be perfectly frank, there is one slight hitch: you’ve never published a line of your work on Evolution. Not one line. As far as the scientific world at large is aware, you have never done any. You don’t even have a paper to present at the meeting...

"...Hmm... Ahh! I know! We can help you create an abstract overnight! An abstract. Get it? Abstract was the conventional word in scientific publications for a summary of an article. It usually ran right below the title. After that came the article itself. Now do you get it, Charlie? All we need is for you to give us an abstract of a scholarly paper of yours that doesn’t exist!"

Darwin was aghast.

"I should be extremely glad now to publish a sketch of my general views in about a dozen pages or so," he wrote to Lyell. "But I cannot persuade myself that I can do so honourably... I would far rather burn my whole book than that he or any man should think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit."

In fact, he said, he had been intending to write Wallace relinquishing all claim of priority when Lyell’s letter arrived. So how could he possibly concoct his own essay overnight and raise his hand and claim priority himself?

How very paltry.

Darwin had taken to repeating this word, “paltry,” over the last few days. It meant “small-minded,” “mean,” “vile,” “despicable.” Not a pretty word, but a lot better than “dishonest.”

—Hold on a second: what’s that? A tiny hole... or is he just seeing things?...

No, there’s a tiny hole in Lyell’s letter, the tiniest hole you ever saw in your life... and through that hole shines a little gleam of light, so little he wonders if it could possibly be real...

But it is real!

It emits the faintest of glimmers—the faintest of glimmers, but an honourable glimmer!

Darwin pivots 180 degrees. His heart turns clear around.

Or that “was my first impression,” he says to Lyell, suddenly switching gears, “& I should have certainly acted on it, had it not been for your letter.” But your letter... your letter... your letter has shown the way.

Even Stephen, you have ruled. Even Stephen! And who am I to presume to overrule Sir Charles Lyell? You are the dean of British naturalists, my old friend. There is no greater or wiser man in this entire field. Everyone, including Wallace, will be better off in the end if we leave all this in your accomplished hands.

Yes, Sir Charles Lyell had made his decision. The two papers—Wallace’s and Darwin’s—would be made public simultaneously before the Linnean Society. With a single stroke, Sir Charles had made the question of priority disappear.

He, Darwin, would not be claiming priority. Just the opposite. He was extending a magnanimous hand to a newcomer. He would be making room on the stage for a lowly flycatcher to be heard.

The one remaining catch was that Lyell and Hooker expected Darwin to write his own abstract. He couldn’t do that—he mustn’t do that. He begged off with some pathetic excuse. He didn’t have the courage to tell them that his own conscience must be kept clear.

His own conscience had to believe he had nothing to do with this project. It wasn’t his idea. It was entirely theirs—Lyell’s and Hooker’s.

I, Charles Darwin, had nothing to do with it! Above all, let no man be able to say I wrote an abstract for myself after reading Wallace’s paper. There mustn’t be a hint of any such paltriness before an august body like the Linnean.

So it fell upon Lyell’s and Hooker’s shoulders—the task of concocting for Charlie an abstract out of what they could lay their hands on quickly...

Let’s see... we have a copy of a letter he sent last year to an American botanist at Harvard named Asa Gray, giving a halfway outline of his concept of natural selection... and there’s some sort of abortive “sketch,” as he calls it, that he has at home for a book on transmutation he’s been telling himself—for the past fourteen or fifteen years—he’s going to write someday.

And of course, we have Wallace’s paper for... hmmmm... how should one put it?... for “background” or “context” or maybe something along the lines of “corroborative research” or “heuristic monitoring.” We’ll think of a term.

In any case, we’re in a position to make sure there will be no important points in Wallace’s paper that aren’t also in Charlie’s.

Hooker’s wife, Frances, is a bright little number. We'll get her to read Wallace’s letter and then pull together some extracts from Charlie’s “sketch”... and, while she’s at it, shape things up a bit... where necessary.

There is more than one way to swat a flycatcher.

When they were finished, Darwin had two papers to his name, both very short—first, an abstract of his letter to Asa Gray, and second, the extract of his unpublished sketch, tidied up by Mrs. Hooker. Combined, they were almost as long as Wallace’s twenty pages.

To put the matter in perspective, one has only to imagine what would have happened had the roles been reversed.

Suppose Darwin is the one who has just written a formal twenty-page scientific treatise for publication... and somehow Wallace gets his hands on it ahead of time... and announces that he made this same astounding epochal discovery twenty-one years ago but just never got around to writing it up and claiming priority...

A hoarse laugh?

He wouldn’t have rated anything that hearty. Maybe a single halfway-curled upper lip—if anybody deigned to notice at all.

At the Linnean Society meeting on July 1, neither party was present.

Not Wallace, because the Gentlemen had been more than content to leave the flycatcher in the dark in equatorial Asia, 7,200 miles away...

And not Darwin, because his infant son, Charles Waring Darwin—his and Emma’s tenth child after nearly twenty years of marriage—had died of scarlet fever on June 28.

He couldn’t very well show up in public three days later, on July 1, advancing his career beneath a banner saying:

HUMAN BEINGS ARE NOTHING BUT ANIMALS.

At Linnean Society meetings, papers on a single subject were read in alphabetical order, by author—and wouldn’t you know it?—D comes before W. That was just the way it goes sometimes, too.

So the Society heard two of its most distinguished members, Sir Charles Lyell and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker—peers of the realm—do the introductions, which were spent pointing out that Darwin, who clearly had priority, was all for including Wallace on the program.

Both authors may “fairly claim the merit of being original thinkers in this important line of inquiry,” Lyell and Hooker began, but Darwin was the first... it just took him twenty-one years to get around to writing his thoughts down.

Then the Linneans heard not one but two papers by their renowned colleague Charles Darwin, member of the Royal Society of London, famous for his many years of worldwide explorations... and then one by some little flycatcher named Wallace.

It was not hard to get the impression that the distinguished Mr. Charles Darwin, with his big heart, was giving a pat on the head to this obscure but promising young man off catching flies in the tropical bowels of Asia.

That impression never changed.

Wallace was an outsider and not a Gentleman—not the Linnean Society sort. An undersecretary read the introduction and all three papers aloud. They prompted no questions or discussion; none at all.

Most of the twenty-five or thirty Linneans on hand appeared bored, if not put to sleep, by the drizzle drizzle of species transmutation, biogeographical variations, injurious adaptations—drizzle drizzle... When, O Lord, will the fog clear out?

They had come to hear Lyell—a Gentleman among Gentlemen—deliver a promised eulogy of the Society’s lately departed former president, which he did, first thing. As for the rest of the program, they did their best to endure... the first public revelation of a doctrine that would turn the study of man upside down—and kill God, if Nietzsche had anything to say about it.

At the moment, however, the Gentlemen of the Linnean Society greeted the news with yawns so big they couldn’t cover them with their bare hands.

In his annual state-of-the-society speech the following spring, the Society’s president said:

“The year which has passed... has not, indeed, been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science on which they bear.”

Thoroughly enjoyed this, thank you.